I had never considered myself a very maternal person, so when I fell pregnant unexpectedly I was shocked by the sudden array of unconditional love and overwhelming sense of protectiveness I suddenly felt. My pregnancy was relatively stressful but when I gave birth to my beautiful son, Tayden, all of the anxieties I'd had were replaced by a feeling of intense joy. The night after he was born, I couldn't sleep, despite my exhaustion—I was so in awe of him. It felt surreal that after 9 months of wondering how he would look and what it would feel like to be a mother, he was there, the most precious and perfect gift I had ever received. I spent hours just looking at him, not believing he was really mine. I adored his every feature, movement and expression, and felt like the luckiest woman alive. Tayden was the first true love of my life.

Born on a sunny Saturday morning in May, a healthy baby boy with an equally healthy set of lungs, Tayden changed my world. When I brought him home I was filled with excitement and nerves as I stumbled my way through dirty nappies and regular feeds. But 2 days after we arrived home, my joy became overshadowed by an uncomfortable feeling when I began to notice that Tayden didn't seem to cry. He was abnormally quiet, with the exception of a loud wheeze and irregular breathing pattern. I was reassured by friends, family and midwives that his silence was quite normal for newborns and that his lethargy was attributable to jaundice. During my pregnancy, Tayden had been a very active baby, yet now he would sleep for hours on end. As much as I wanted to believe he was content and relaxed, I couldn't avoid the instinctive feeling of worry. I often found myself having to tap him gently when he was asleep, just to check he was still breathing—he seemed so lifeless.

I called my local midwifery service to no avail and eventually decided to take him to A&E. When asked what was wrong with him, I felt stupid saying that he simply didn't cry and slept a majority of the time. Surely most mums would be relieved to have a baby like this?

After an array of tests, I was assured that if there was anything seriously wrong with him, I would know about it because he would be screaming the place down. A silent baby was deemed a healthy baby. This temporarily comforted me, until a doctor attempted to take blood from him and he did not flinch or make a sound. Immediately, I expressed concern that something could be wrong with his brain, as he seemed unable to register the pain yet it was clear from his face that he was in discomfort. I was baffled as to why the pain of inserting a needle hadn't aroused any reaction from my son. My concerns were dismissed and we were sent home. I had assumed newborn babies would be kept in overnight as a precaution, but nobody seemed particularly worried and he was deemed well enough to go home. Driving home, I wondered if I had fallen victim to becoming a hysterical first-time mum.

Deteriorating condition

Over the next 24 hours, Tayden became ever less responsive, the wheeze became louder, his breathing more erratic. A midwife visited Tayden and when he had a heel-prick test, he barely opened his eyes. I returned to A&E insisting that he be admitted, and eventually after three failed Moro reflex tests he was sent to the birthing centre and placed on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

I was convinced, despite everyone's well-meaning advice, that he was seriously ill, yet all the while I couldn't explain why I felt that way—perhaps it was a mother's instinct. Tayden was kept in overnight and became increasingly unresponsive. I felt frustrated that none of the medical professionals involved in his care seemed to listen to me or take my concerns seriously. Later that night, Tayden's body became floppy, and eventually we saw a doctor who confirmed they would do a lumbar puncture as they suspected he might have meningitis. Finally, I felt I was being listened to and my anxieties acknowledged, which was both a blessing and a curse.

‘When asked what was wrong with him, I felt stupid saying he simply didn't cry and slept a majority of the time. Surely most mums would be relieved to have a baby like this?’

Tayden spent 4 days in the intensive care baby unit, where he had brain scans, blood tests and viral cultures taken. Opinions about his diagnosis ranged from pneumonia to septicaemia or Group B streptococcus. His care in hospital was impersonal and I felt that the medical team were irritated by my relentless need for answers. There was a lack of senior-level presence and experience on the ward. I simply couldn't understand how my healthy baby boy was worsening by the hour, on morphine and receiving respiratory support, yet still there were no definitive answers about the cause.

I was assured that Tayden's condition wasn't a ‘life-or-death situation’. Later that evening, Tayden began having convulsions; for me, this was the confirmation I needed that the illness was related to his brain. I felt his treatment up until this point was not adequate or reactive enough, so I asked for him to be transferred to another hospital. Medics crowded around his cot and I was told to wait outside. Seeing Tayden lying there helpless and not being able to comfort him was nothing short of torture. My mind raced with worry and I slumped to the floor, feeling as if my legs couldn't carry the weight of my heavy heart. I could hear loud beeps and saw worried faces all around me, and I felt paralysed with shock. Hours earlier, I had been assured this wasn't life- or-death—now here I was facing just that.

A nurse came to inform me that they were performing life-saving treatment. Those words got lost in sobs and screams as I made my way to the ambulance. I have never hoped and prayed as hard as I did on that journey. On arrival at the hospital, I wasn't allowed to see Tayden for an agonising 5 hours. When I did see him, he was lost in a mass of clinical furniture and medical machines, and on dialysis. His body was three times its normal size and I barely recognised him. I couldn't comprehend the rapid decline in his health. A doctor took me aside and explained that Tayden had neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV). I was stunned as I had only ever associated herpes with adults, as a sexually transmitted infection, and could not understand how it could be possible that my baby had caught it. I had never suffered with herpes in my life, not even a cold sore, and I was utterly confused. Looking back, it was quite an ignorant response, especially now I know so much more about the illness.

In Tayden's case, the virus had been passed on by someone who had close contact with him while they had an active bout of the virus. I was shocked to learn this, as I had never known that babies could contract such a serious condition just by being exposed to someone who had a cold sore. The doctor's words faded as my brain raced as I tried to think of every person who had ever held him, kissed him or been in close contact with him. I almost felt embarrassed to tell my waiting relatives what was wrong with him because it wasn't an illness you would normally associate with a baby.

The doctor confirmed that the illness was incredibly rare, the prognosis was poor and that most babies who had this condition were likely to die or suffer irreversible brain injury. Despite this, I still hoped he would survive—I'd never known of anyone to die from a cold sore.

Understanding the virus

Neonatal HSV affects one or two babies in every 100 000 live births. The usual age for onset of symptoms is between 5 and 21 days of life. Aside from initial prevention and awareness, there is a need for health professionals to consider neonatal HSV much sooner. If undetected, the infection spreads alarmingly quickly, meaning a baby's chance of survival is largely down to the health professional's proactive approach in identifying it or ruling it out during the initial stages of the baby's admission to A&E.

The challenge around diagnosing the infection is that there are three different types, which manifest differently—there is no one-size-fits-all set of symptoms, and signs are often mistaken for other sepsis-related illnesses. In Tayden's case, more attention should have been paid to his extreme lethargy and lack of response to pain, as this represented that he already had brain damage as a result of the illness spreading.

I can't help wondering that if just one medical professional had delved deeper and read between the lines, perhaps I would be telling a very different story today. I later discovered that Tayden's blood results showed an abnormally raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, yet nobody followed it up; this would have been a key indicator that he had organ failure in the first few days of his admission to hospital.

A further blow was dealt when Tayden was diagnosed with acute liver failure. He was transferred to another hospital, where the medical team was amazing. Tayden became affectionately known as everyone's ‘little hero’. One doctor, very kindly, told me that if love worked like medicine then Tayden would have been cured a thousand times over, because he was surrounded by it.

Miraculously, Tayden began showing signs of improvement, but this was cut short when he suffered a cranial bleed to his brain. I was told that nothing further could be done. As a parent, it is impossible to quantify the excruciating pain of hearing those words.

Only 19 days earlier, I had given my son life; now, here I was with his lifeless body in my arms, trying to comprehend the devastating turn of events. When I was told his life support would be removed, I was heartbroken as I watched his heart rate plummet. The happiness he imparted, the hope and joy he had bought into my life, was now a simple flat line on an electronic machine.

‘The pain of losing Tayden to an illness that could have been preventable and treatable, if identified at an earlier stage, propelled me into action. It seemed nobody could give me the answers I needed’

When you lose your child, you lose more than just their physical presence and the promise of who they were supposed to be. You are cheated out of your hopes and dreams of the future that you had planned for them. You return home to an empty nursery that will never be slept in, pack away belongings that no longer belong, and replace ‘Congratulations’ cards with sympathy ones. You bury who you were with your child because part of you dies too, and you are changed forever. Sleepless nights once caused by worrying about the baby are replaced by sleepless nights due to a silence that is too loud to bear.

The pain of losing Tayden to an illness that could have been preventable and treatable, if identified at an earlier stage, propelled me into action. It seemed nobody could give me the answers I needed, so I researched medical journals and clinical trials to learn and understand more. I identified a real lack of information out there, and a great deal of misleading advice for parents.

It is my hope that by sharing Tayden's story, I will heighten the awareness of neonatal HSV among the people who have the power to make the most difference—health professionals. I urge those of you reading this to consider neonatal HSV if you come across a ‘mystery’ baby like Tayden. Please remember that just because a condition is rare, that doesn't mean there is no risk of it, nor does it make the lives lost to it any less important.

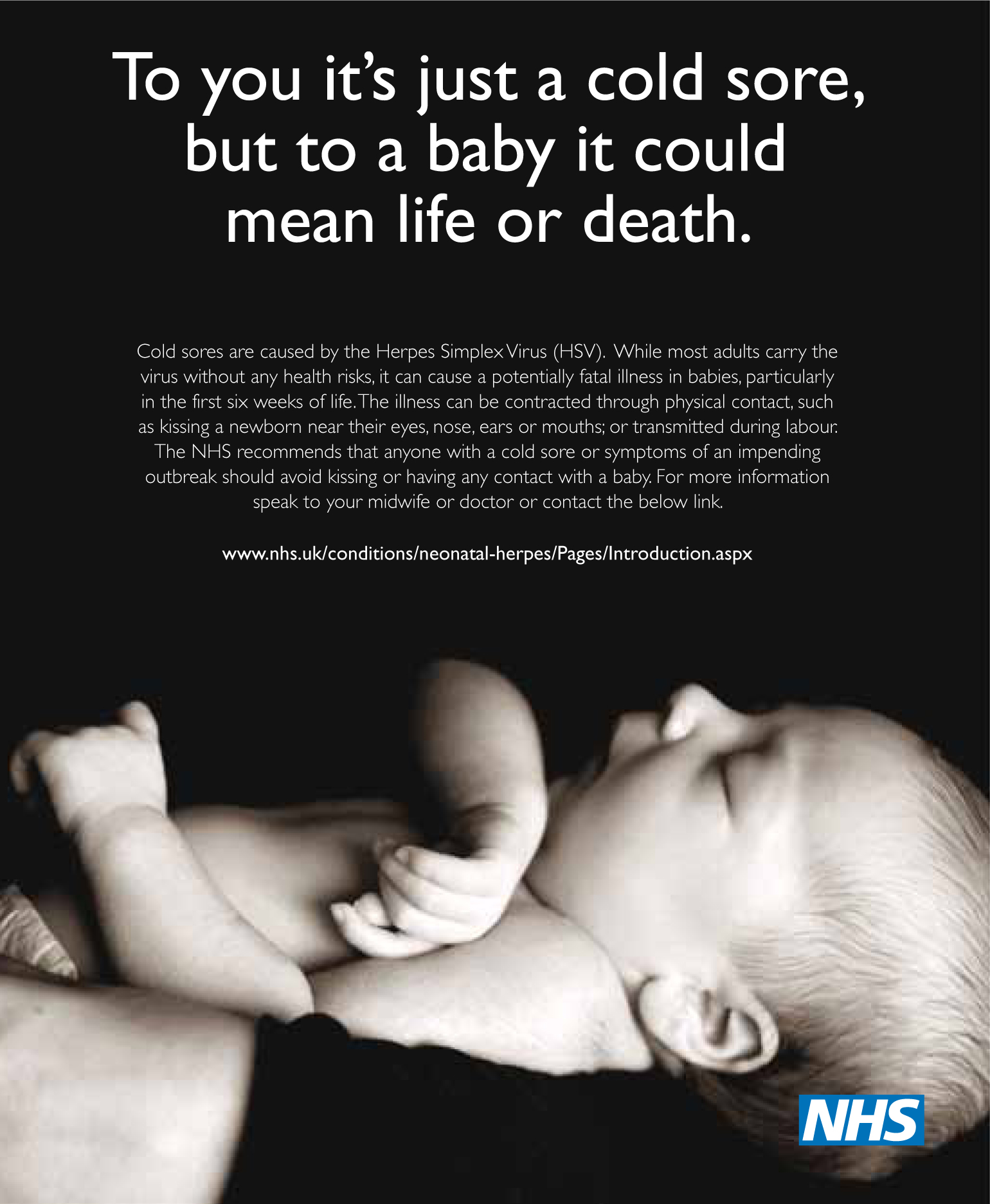

Since November 2012, I have been working in conjunction with NHS England and the Herpes Viruses Association to create an awareness campaign, which is primarily focused on raising the profile of the illness in the health-care and medical domain. I work with different hospital Trusts in London delivering speeches and workshops to keep neonatal HSV in the forefront of practitioners' minds, as well as assisting with research and supporting other mothers who have lost their babies. In the summer, my awareness poster (Figure 1) will be officially launched in London hospitals to warn people of the dangers cold sores can pose to newborn babies.

I wish I could say that achieving success with this campaign has eased my heartache over losing Tayden. It's still bittersweet, but just because I didn't get a miracle to save my child, that doesn't mean I can't help someone else save theirs.