The umbilical cord is the conduit between the placenta and the fetus, transporting oxygen and nutrients while allowing fetal mobility (Sherer et al, 2021). Among its anatomical alterations, those associated with length, diameter, insertion, number of vessels, coiling and entanglements are widely recognised as causes of unfavorable outcomes (Olaya-C et al, 2018). This case study describes two cases of an uncommon umbilical cord abnormality, one fetal and one neonatal, for which very few descriptions are found. The case studies were carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and all procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio (MF-CIE-0533-24).

Case 1

The first case involved a 33-year-old woman (gravida 4, para 2, miscarriage 1) at 34 weeks' gestation with a medical history of chronic hypertension, treated with nifedipine, alpha methyldopa and metoprolol. She also received acetylsalicylic acid and calcium supplementation as prophylaxis.

She was admitted with severe range blood pressure (≥160/110 mmHg), and was asymptomatic without end-organ damage. Fetal wellbeing was assessed by cardiotocography. Severe pre-eclampsia without expectant management criteria was considered the cause, so pharmacologic fetal lung maturation with betamethasone (Hall et al, 2024) was initiated, as well as labor induction with oxytocin. The patient presented severe range blood pressure again, associated with oppressive frontal headache that was not relieved by paracetamol. A caesarean section was performed as a result. Subsequently, new severe blood pressure was recorded and treated with two antihypertensive bolus doses and the patient was stabilised.

A male infant weighing 1820g was delivered, with Apgar scores of 8/10 and 9/10. During adaptation, he presented transient tachypnea of the newborn and required continuous positive airway pressure, and so was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. He received a dose of exogenous surfactant and oxygen supplementation using a low-flow nasal cannula. He was discharged with oxygen and ambulatory controls in the Kangaroo Mother Care Program (Minsalud, 2017).

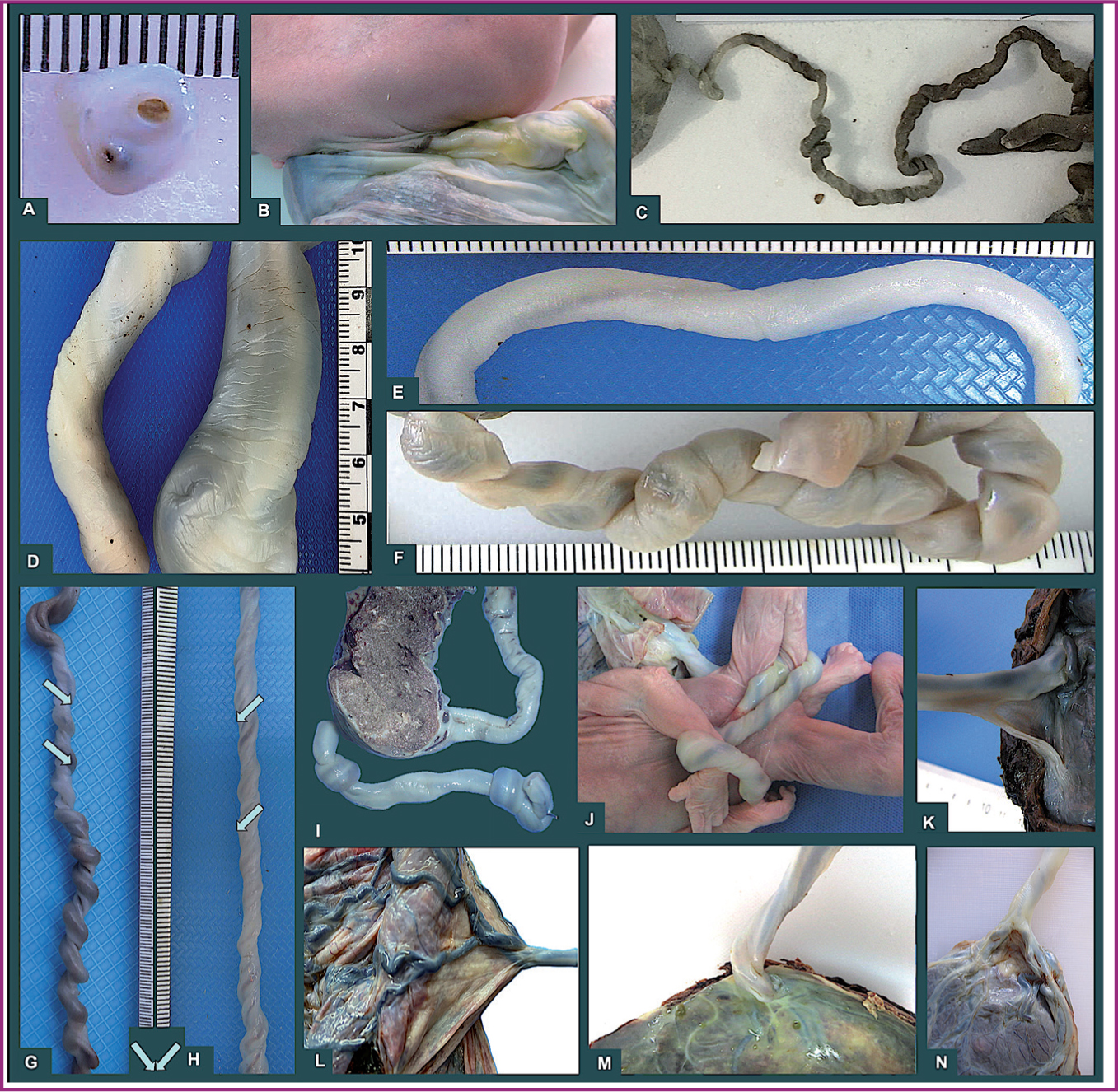

The placental pathology evaluation showed it was circular, weighing 235g and measuring 14 x 13.5cm, with thickness ranging between 2.5 and 1.0cm. On the fetal side, an 18 x 1.5cm umbilical cord was observed; it was trivascular, white and had one coil to the right and central insertion. Along its length of approximately 7cm, there was a partial separation of the vascular structures, with one of the umbilical arteries separated from the other two vessels by a membrane (Figure 1, left). There were no other abnormalities in the placenta.

Histologically, intervillous thrombus was observed, along with perivillous fibrin deposition as maternal vascular malperfusion. There was retroplacental hemorrhage/hematoma, increased syncytial trophoblast knots and wide acute infarction. There was chorionic surface vessel ectasia, vascular intramural fibrin deposition and stem vessel obliteration as fetal vascular malperfusion. In the membranes, decidual arteriopathy was observed, including fibrinoid necrosis, acute atherosis, mural hypertrophy, persistent muscularisation, arterial thrombosis by fibrin and chronic perivasculitis. The cord showed a membrane between two of the vessels.

Case 2

A 21-year-old woman (gravida 2, ectopic 1) at 14.6 weeks' gestation was admitted for one day with light brown, intermittent vaginal bleeding. She had previously sought obstetric consultation for the same bleeding.

In the first emergency admission, transvaginal ultrasound reported an endometrial hematoma involving more than 50% of the gestational sac; however, there was a normal decidual reaction. Additionally, fetal cardiac activity was confirmed both in the first and in the following two admissions, so it was considered a threatened miscarriage. On gynecological examination during the last admission, an open external os of the cervix was observed. Transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasounds reported a single fetus with absent cardiac activity and so it was considered a missed miscarriage. Dilation and curettage were performed.

In clinical fetal necropsy, the fetus was identified as a male of approximately 12 weeks' gestation by biometry, with advanced maceration signs and major and minor malformations, including left unilateral cleft lip and palate, penoscrotal transposition, omphalocele, pulmonary artery stenosis, left renal agenesis, agenesis of vermiform appendix, prognathism, contractures in four extremities, bilateral antecubital pterygium, clinodactyly of the left fifth finger, digitalisation of the left hand first finger and right radial agenesis with hypoplastic third finger. Microscopic examination did not reveal other pathological changes.

The placenta was fragmented, weighing 19g. An umbilical cord with a single umbilical artery was found with paracentral insertion measuring 8.5 x 0.1cm, which was short, as the expected value for age is 13cm. It was hypocoiled (coiling index of 0). Additionally, it showed a membranous separation between its two vessels (Figure 1, right). Fetal morphology and placental microscopic features were compatible with a chromosomal disorder.

Discussion

The umbilical cord is indisputably important for fetal life, newborn prognosis and fetal programming of adult disease. It is considered an extension of body circulation and the axis of novel neuroplacentology (Leon et al, 2022). In order to understand some unexpected outcomes, the anatomical features of the umbilical cord should be highlighted. The most common abnormalities are as shown in Figure 2 and are related to:

Insertion was connected to the anatomical abnormality described in this case study. In both cases, the umbilical vessels were separated without sufficient Wharton's jelly; simultaneously, they were joined by a flattened membrane far from the insertion site into the placenta.

In the literature, only two other similar cases have been described, referred to as ‘funiculi furcata’. The term ‘insertio funiculi furcata’ was coined in 1923 to describe umbilical cord insertion in the placenta, which is now known as ‘furcate cord insertion’ (González Manzanilla et al, 1996). This condition involves branched vessels lacking Wharton's jelly protection before reaching the placenta. Etymologically, ‘funiculus’ refers to the umbilical cord, and ‘furcata’ means forked or branched. The term accurately describes what was seen in the umbilical vessels in these cases; however, the alteration ran along the cord, far from its insertion site. Thus, the authors suggest including the location when classifying this abnormality: medial funiculi furcata.

The authors were able to verify the rarity of these cases: of the 1170 cases registered in the REDCap (2019) database of perinatal pathology, the two cases described are the only ones recorded between 2019 and 2024 (<0.2% of cases).

Both cases presented the same apparency: the first in the context of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with neonatal complications, and the second in a malformed fetus with umbilical cord alterations. Both conditions have been associated with umbilical cord anatomical abnormalities. The most common finding in preeclampsia is a thinner or leaner umbilical cord (Ferguson and Dodson, 2009), as well as hypocoiling (Goynumer et al, 2008), but other abnormalities have been described (Olaya et al, 2016). Association between chromosomal disorders and umbilical cord abnormalities is also known, and leaner diameter (Rembouskos et al, 2004), abnormal insertion (Hasegawa et al, 2006), single umbilical artery (Kaplan, 2007) and hypocoiling (de Laat et al, 2006) have been reported.

Conclusions

Despite years of observing the macroscopic appearance of the umbilical cord, anatomical alterations continue to emerge, often associated with fetal disorders or maternal complications during pregnancy. Careful observation of the umbilical cord provides important information about intrauterine life course.