‘Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.’ When Eleanor Roosevelt delivered these remarks to the United Nations in 1958, we at Birthrights like to think she had in mind those places where women give birth.

Human rights can seem like a lofty concept but at its heart its really very simple. It's about treating every individual as a human being because they are worthy of respect. The past year has been like no other for all of us. And human rights has been a potent lens through which to view the pandemic. The remarkable thing about the framework of human rights law, embodied in the European Convention of Human Rights and incorporated into UK law through the Human Rights Act 1998, is that it is flexible enough to meet the challenges of coronavirus head on.

Yes, there are absolute rights; to be treated with dignity and respect, to have your basic needs met, to access safe care, that should never be eroded. But there are also qualified rights, in particular the right to private and family life. These rights can be restricted but only if the restriction is necessary to control the spread of the virus and protect the health of others in this case but any restriction must be ‘proportionate’.

We have seen the argument about what is ‘proportionate’ play on our TV screens night after night. Livelihoods lost versus lives lost; personal freedoms versus the wellbeing of all. We have campaigned to see this balancing act conducted much more explicitly and transparently in maternity services during the pandemic. The impact of any changes on service users and staff must be thoroughly considered. COVID-19 is serious but it does not trump all.

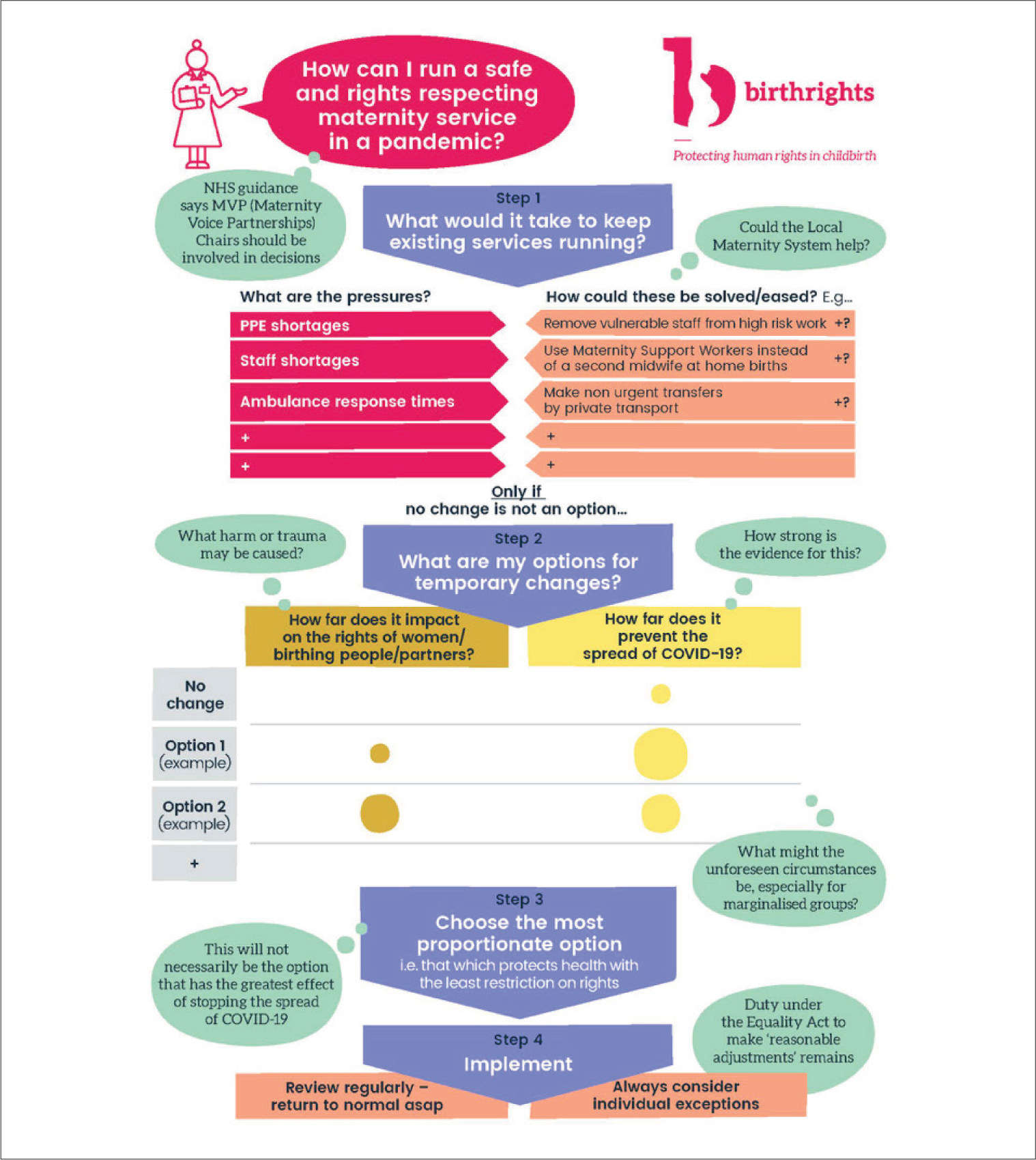

Tool created by Birthrights to help maternity services make decisions during the pandemic

Tool created by Birthrights to help maternity services make decisions during the pandemic

Information and advice

The first symptom of coronavirus for Birthrights, besides staff getting to grips with the work and home-schooling juggle, was a huge increase in enquiries to our advice line. We received nearly five times the amount of enquiries in March 2020 as we did in March 2019, and at the time of writing, we have answered around three times the number of enquiries this year (since April 2020) compared to the previous year.

Enquiry themes echoed the changes that have been rippling through maternity services. An avalanche of enquiries about home birth services being suspended, birth centres being closed, water births and even caesarean sections being withheld gradually gave way to a steady stream of enquiries from those affected by visitor restrictions in particular.

The contrasting approaches of trusts and boards has been apparent. We know some trusts have gone into the pandemic better prepared to reshape their service around the needs of women, having already advanced well down the road to continuity of care, and having strong leadership in place. We have also heard from midwives facing moral dilemmas about changes to the services in which they work, and facing fear for their own health, and that of their families, as well as an increasing risk of burnout.

We have consoled, supported and empowered women/birthing people and their families, advised healthcare professionals, written to trusts, created resources, and lobbied NHSE, the Royal Colleges and devolved governments to bring about change, as a result of what we have heard from those contacting us.

Training

Birthrights trains over 1 000 healthcare professionals each year and we now have a team of around 30 associate trainers who deliver this training on our behalf. Our trainers are mostly lawyers or healthcare professionals who have other jobs but who are happy to give up their time for Birthrights, for which we are very grateful. Despite all training and speaking engagements moving online, we have reached over 3 000 healthcare professionals and birth workers in the last year. We have used Zoom to make sure we can retain our small group discussions around case studies, as well as getting to grips with polls, jam boards (virtual post-its) and much more! And we are pleased to say that the feedback has been fantastic.

We know that no one starts working in maternity care with the intention of harming women but the systemic pressures are strong. Those that have done our training say that they feel empowered to listen to women, to respect their decisions, and deliver the individualised care they want to deliver knowing that the law is on their side. If you would like to know more about our training, please visit our website (https://www.birthrights.org.uk/) or get in touch at info@birthrights.org.uk

Wider policy and campaigning work

Our model is to use what we learn from women and their families, and from working closely with healthcare professionals to inform our wider policy and campaigning work. This gives us a strong grounding in the reality of what is happening in maternity services from all perspectives, which has proved very useful in the fast changing currents of this year. And there has been lots of change for us an organisation too. We have had a significant profile in the media this year, we have formed new alliances with organisations such as Pregnant then Screwed around shared goals, and we have forged new relationships with the devolved governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Use of the law is one of our areas of expertise. While we always use this sparingly and strategically, it can be a uniquely powerful lever of change. For example, in January we commissioned external legal advice, which we shared publicly, which challenged the stance of many trusts on filming/streaming of scans, given the evidence on the clinical benefits of involving partners.

Looking forward

During 2021, we will be turning our attention back to other human rights issues in maternity care. In particular, we are facilitating an inquiry into the maternity experience of black and brown women, given the stark inequalities in outcomes faced.