As a result of advances in medicine, midwives and obstetricians are increasingly seeing a number women with complex medical histories. This may include women who have been born with hydro cephalus, or who have idiopathic intracranial hyper tension. This article will examine the issues faced by women with shunts draining cerebrospinal fluid into the peritoneal cavity during their pregnancy.

Hydrocephalus and intracranial pressure

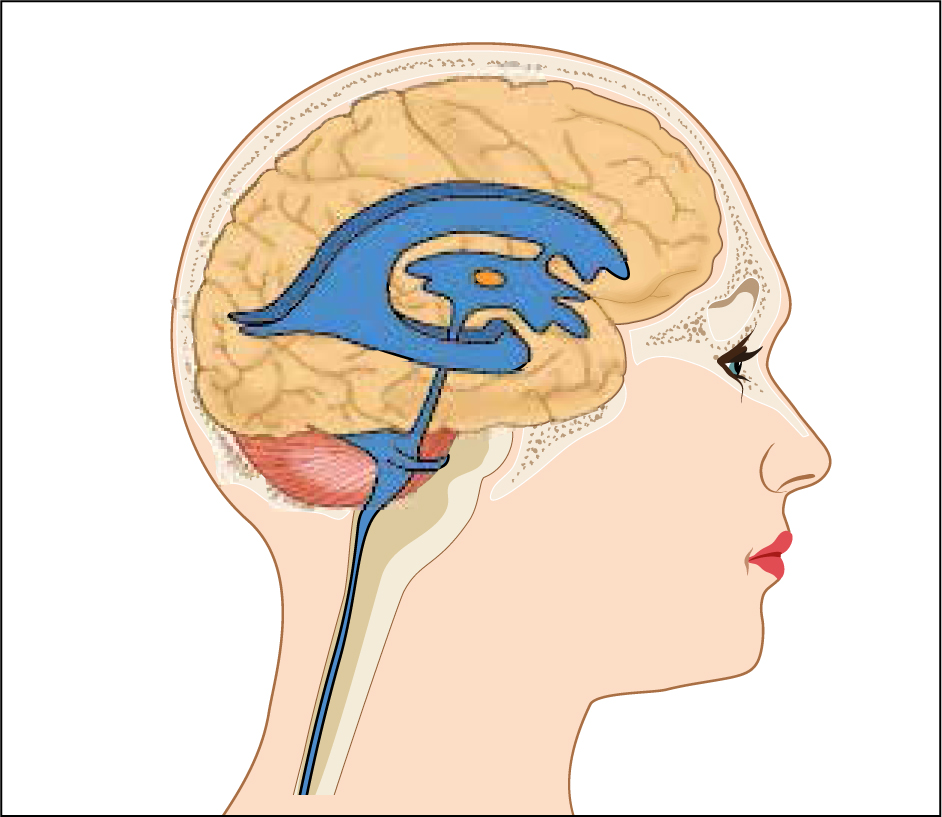

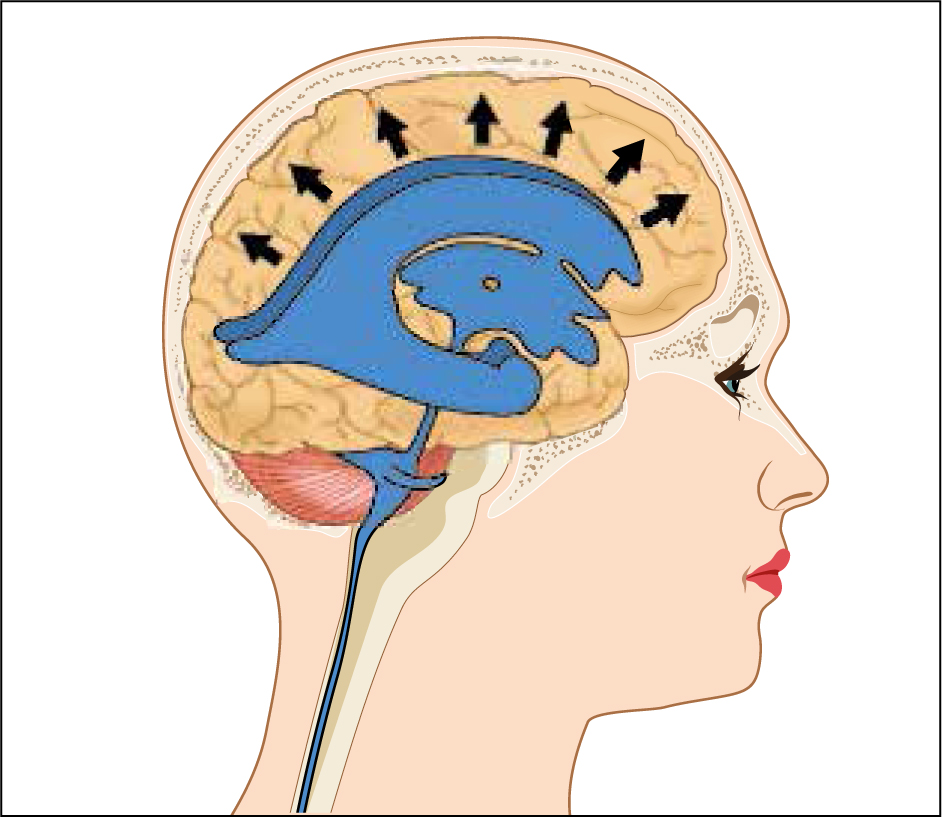

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is continually produced by the chloride plexus located within the lateral and fourth ventricles of the brain (Figure 1). In adults, around 500 ml is produced per day, with a circulating volume of approximately 150 ml (Sakka et al, 2011). Hydrocephalus is a complex condition resulting in an increase in CSF. It can be caused by a primary or secondary condition. This increase in fluid causes a rise in intracranial pressure (ICP) (Figure 2), which can lead to neurological deterioration. Symptoms include reduced conscious level, headaches, nausea, papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) which can cause visual deterioration, and issues with gait (Samandouras, 2010). Treatment options vary depending on the cause. In cases where hydrocephalus is the result of another underlying condition, such as a brain tumour, an operation to treat the primary cause, such as reduction or removal of the tumour, may be sufficient to improve the flow of CSF and therefore treat the hydrocephalus. In most cases, however, a CSF shunt is required; this will drain the excess fluid to another location, from which it is reabsorbed.

A CSF shunt can also be used to treat idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), which involves an increase in ICP with no known cause. IIH is commonly treated with a CSF shunt to reduce intracranial volume and thus intracranial pressure. IIH can present in all age groups but is most commonly found in women of childbearing age: 20–40 years. It has a prevalence of around 10.9 per 100 000 women in the UK (Raoof et al, 2011). It can be treated with acetazolamide, which reduces the production of CSF; however, this is contraindicated in pregnancy. In more complex or aggressive forms, CSF shunting is required.

CSF shunts

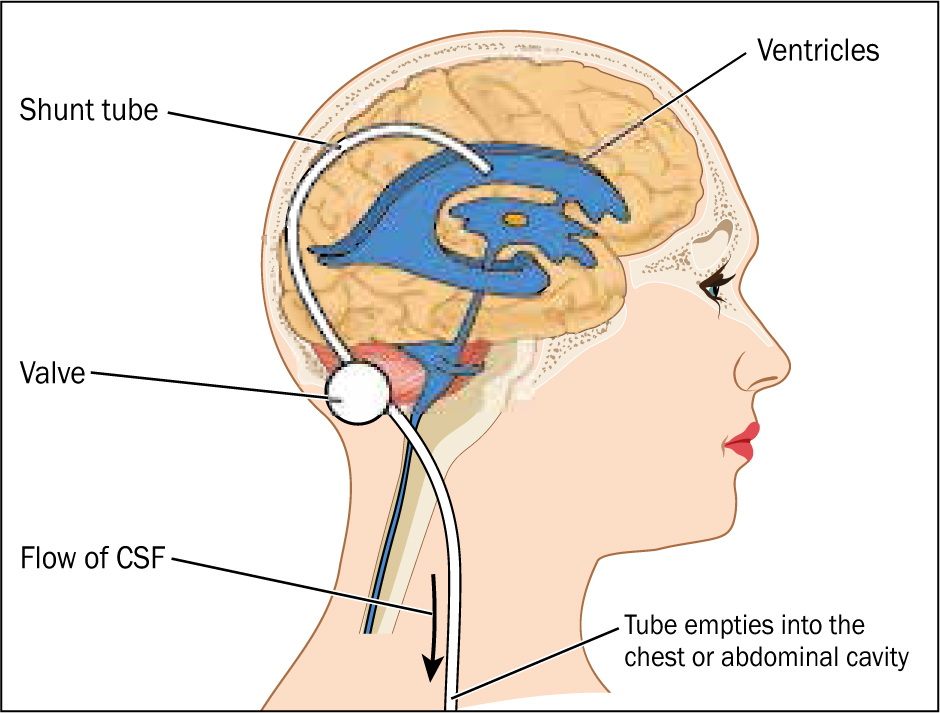

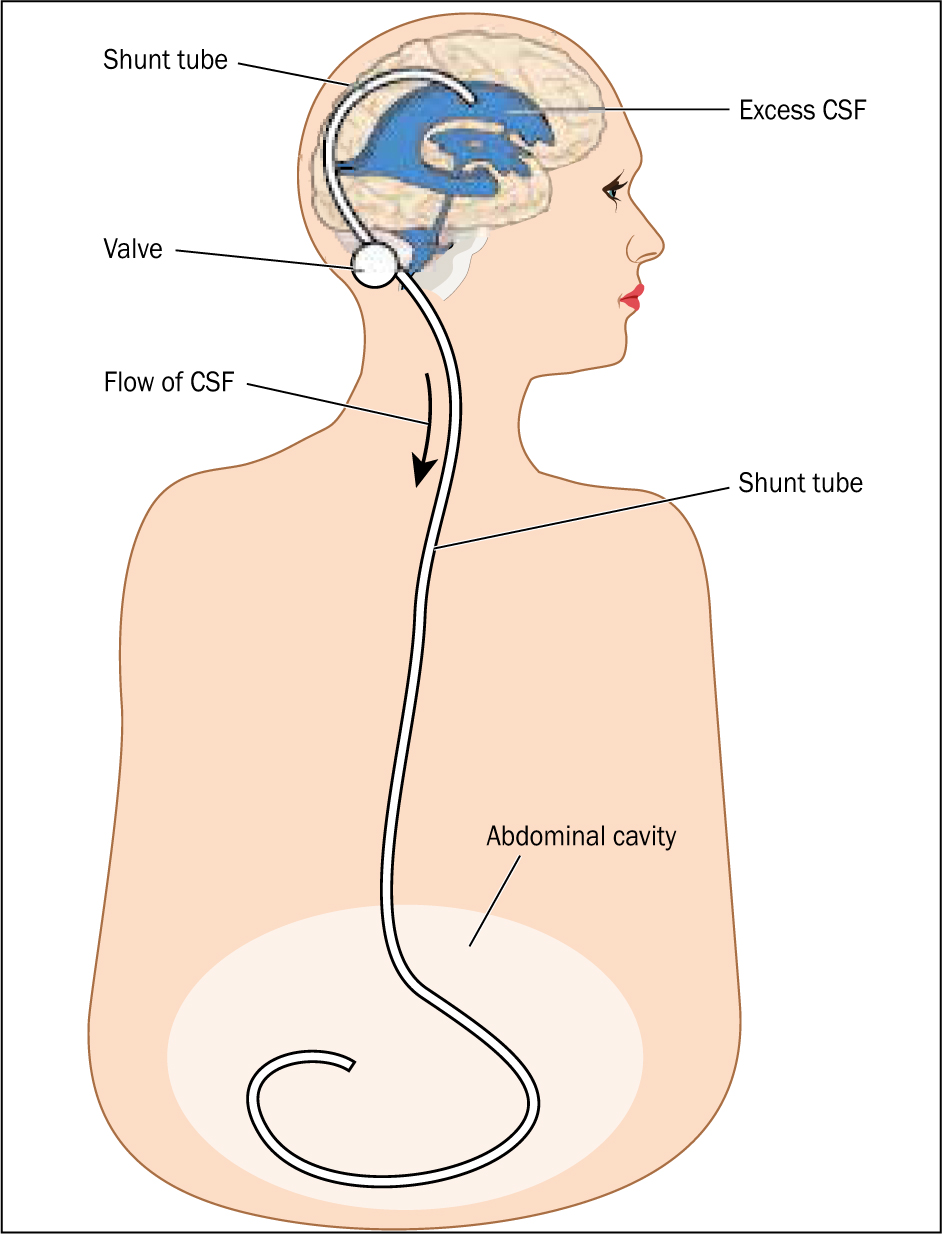

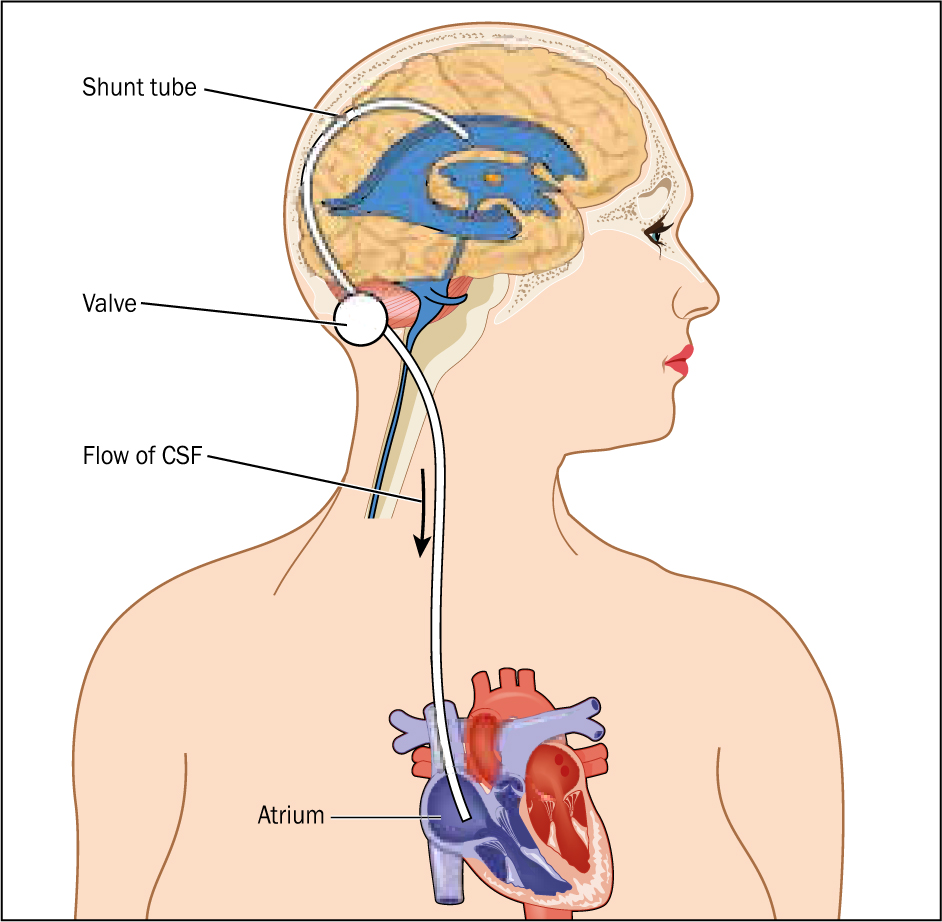

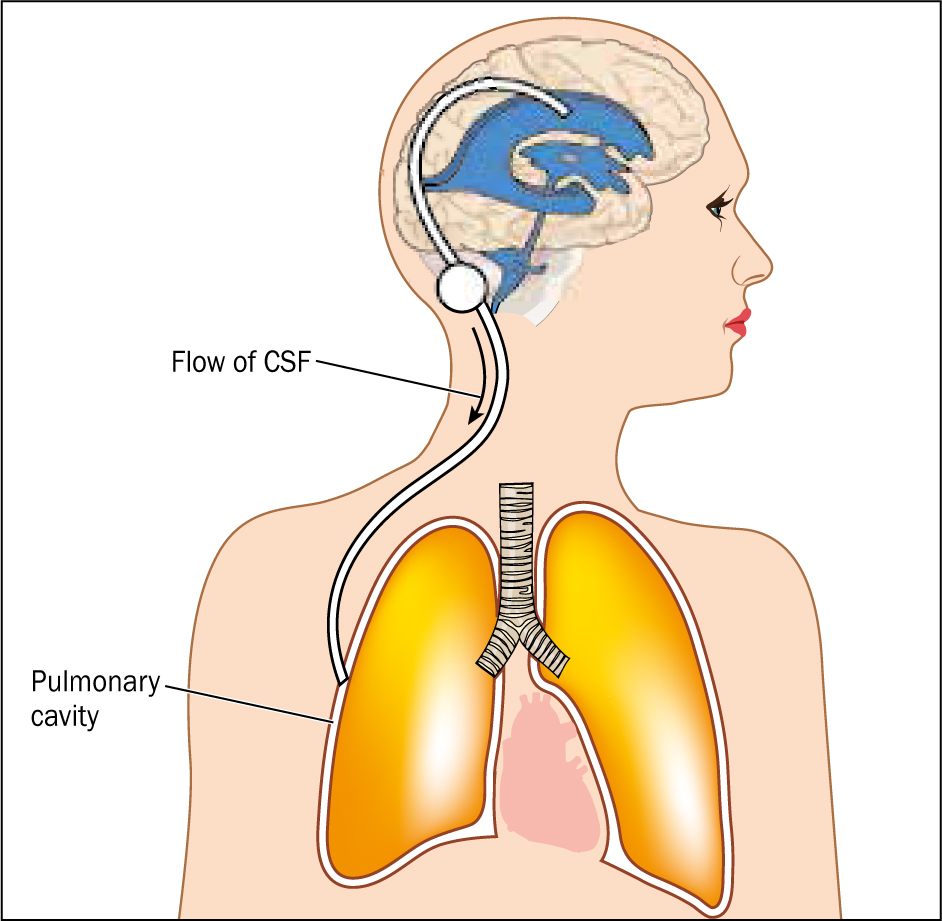

The most common treatment for the redirection of CSF, as in the cases of hydrocephalus and raised ICP, involves the insertion of a CSF shunt into either the lateral ventricles within the brain or the lumbar dura. This tubing is then internally tunnelled to another area of the body when the fluid is drained and reabsorbed (Figure 3). The most common destination for CSF shunts is the peritoneal cavity (ventriculoperitoneal (VP) (Figure 4) or lumbarperitoneal (LP) shunt), followed by the atrium of the heart (ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt) (Figure 5) and pulmonary cavity (ventriculopleural (VPl) shunt) (Figure 6), if the peritoneal cavity is unsuitable.

In most cases, the shunt will include a valve to prevent too much CSF from being drained. When the ICP reaches a preset threshold, the valve opens and CSF will drain via the shunt. The valve will then close when the pressure reduces. Technological advances in the past 25 years have meant that these valves can be magnetically adjustable, meaning that clinicians can non-invasively change the resistance of the shunt valve, thus draining more or less CSF and reducing or increasing ICP once the valve is implanted.

Complications with pregnancy

In peritoneal shunts, the distal tubing is inserted into the peritoneal cavity. The greater the pressure within the abdomen, the higher the ICP required to drain CSF via the shunt. In some patients who are overweight or pregnant, such shunts are not ideal as these patients commonly have raised intra-abdominal pressure. This rise makes it harder for the shunt to drain CSF (Miele et al, 2004; Sahuquillo et al, 2008).

Most pregnant women with a shunt are likely to experi ence deterioration in their condition during pregnancy. This is due to hormonal changes but also to an increase in plasma volume, weight, and thus raised intra-abdominal pressure, leading to reduced CSF drainage. These problems commonly occur in the third trimester and during labour, mainly owing to the increased size of the fetus. This increases intra-abdominal pressure and makes it harder to drain CSF (Fletcher et al, 2007).

According to Wisoff et al (1991) around 76% of women who have a shunt are likely to have a problem in their condition during pregnancy, with 59% experiencing increased ICP, 12% seizures and 6% increasing headaches. In some cases, women may need a reduced shunt setting (if an adjustable shunt is in place); this will encourage greater CSF drainage if symptoms deteriorate. In other, more acute situations, the peritoneal cavity may not be able to sufficiently drain CSF. This can result in the preterm delivery of the baby (Schiza et al, 2012). If the stage of pregnancy is < 34 weeks, the shunt tubing can be externalised, which would allow the drainage of CSF. Bradley et al (1998) reported that around 16% of pregnancies experienced a shunt failure and required a surgical revision during their pregnancy.

It has been proposed that, if a woman experiences difficulties with a VP shunt during pregnancy, it should be converted to a VA shunt (Murakami et al, 2010). This is because this type of shunt is not affected by any rise in intra-abdominal pressure. Some studies have gone further, suggesting that all women of childbearing age should have a VA shunt as a firstline treatment (Okagaki et al, 1990). There is a dearth of more recent literature on this topic.

Vaginal birth or caesarean section?

A woman who has a VP shunt can have a normal vaginal birth. During labour—particularly during the second stage—women will experience a rise in intracranial pressure through straining (Bagga et al, 2005). This will intensify their symptoms. There are case studies that report raised ICP during normal birth resulting in papilloedema, with no untoward effects (Huna-Baron and Kupersmith, 2002). If a woman decides to have a vaginal birth, a prolonged second stage of labour should be avoided. A shortened second stage of labour is preferable to reduce longer periods of raised ICP (Cusimano et al, 1990; Hwang et al, 2010). This has been reported to cause severe headache in some women (Liakos et al, 2000), and in some cases, an assisted delivery is an appropriate. This should be discussed fully with the woman during the antenatal period.

Although there is no evidence that an elective caesarean section is required for women with a CSF shunt (Kuba and Kroll, 1998), the mode of birth needs to be discussed with the woman and the multidisciplinary team. Every birth is unique and, for the woman, an elective caesarean section may be the preferred option depending on her symptoms (Bagga et al, 2005).

If a caesarean section is performed and the shunt tubing is observed in the peritoneum during the procedure, a sterile technique should be maintained and, ideally, the tubing left in the peritoneal cavity. This may increase the risk of intra-abdominal infection around the distal shunt tubing (Bryant et al, 1988). To minimise the chance of infection here, care should be taken to thoroughly irrigate the peritoneal cavity (Bradley et al, 1998). Once this happens, clinicians are strongly advised to contact their local neurosurgical team to discuss appropriate management and follow-up for the woman.

Type of anaesthetic during birth

Regional anaesthetic can be used for both vaginal births and caesarean sections (Schiza et al, 2012). The type of anaesthetic technique used for caesarean sections in cases where the woman has a VP shunt depends on various factors, such as the extent of the woman's ICP, her neurological condition and her wishes (Schiza et al, 2012). It has been suggested that women with elevated ICP and deteriorating neurological condition should have a general anaesthetic for birth (Littleford et al, 1999); however, Freo et al (2009) point out that this is not without risk.

Conclusions

With increasing life expectancy of conditions such as hydrocephalus and a higher number of shunt insertions, greater numbers of women who have a CSF shunt are likely to become pregnant. Having a CSF shunt can make pregnancy more complicated. It is important for women to see their midwife, obstetrician and neurosurgeon early in their pregnancy so potential issues can be identified and plans can be discussed. Women with a CSF shunt will benefit from having continuity of care so that any changes in their condition can be identified immediately. Having a CSF shunt does not automatically mean a woman will require a caesarean section, but prolonged labour should be avoided and assisted birth contemplated.

The most important factor is that each woman is treated individually, with midwives and other health professionals responding to her condition sensitively as the pregnancy progresses.