It is estimated that 85% of women will sustain some degree of perineal trauma during vaginal delivery and 60–70% of these will require suturing (Kettle and Tohill, 2008). Perineal trauma includes not only trauma to the perineal muscles but more extensive tears during vaginal delivery such as obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIs), collectively known as third and fourth degree tears, and isolated rectal button hole tears. Perineal tears are classified according to the widely accepted Sultan classification outlined in Table 1. The incidence of perineal tears varies significantly depending on parity, location of delivery and mode of delivery (Smith et al, 2013). The overall incidence of OASI in the UK is 2.9%, with a higher incidence in primiparae (6.1%) compared to multiparae (1.7%) (Thiagamoorthy et al, 2014; Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology [RCOG], 2015). Although the exact incidence of rectal button hole tears is not known, these injuries are rare (Vergers-Spooren and de Leeuw, 2011).

| Grade of trauma | Extent of injury |

|---|---|

| 1st degree tear | Injury to perineal skin and/or vaginal mucosa |

| 2nd degree tear | Injury to perineum involving perineal muscles but not involving the anal sphincter |

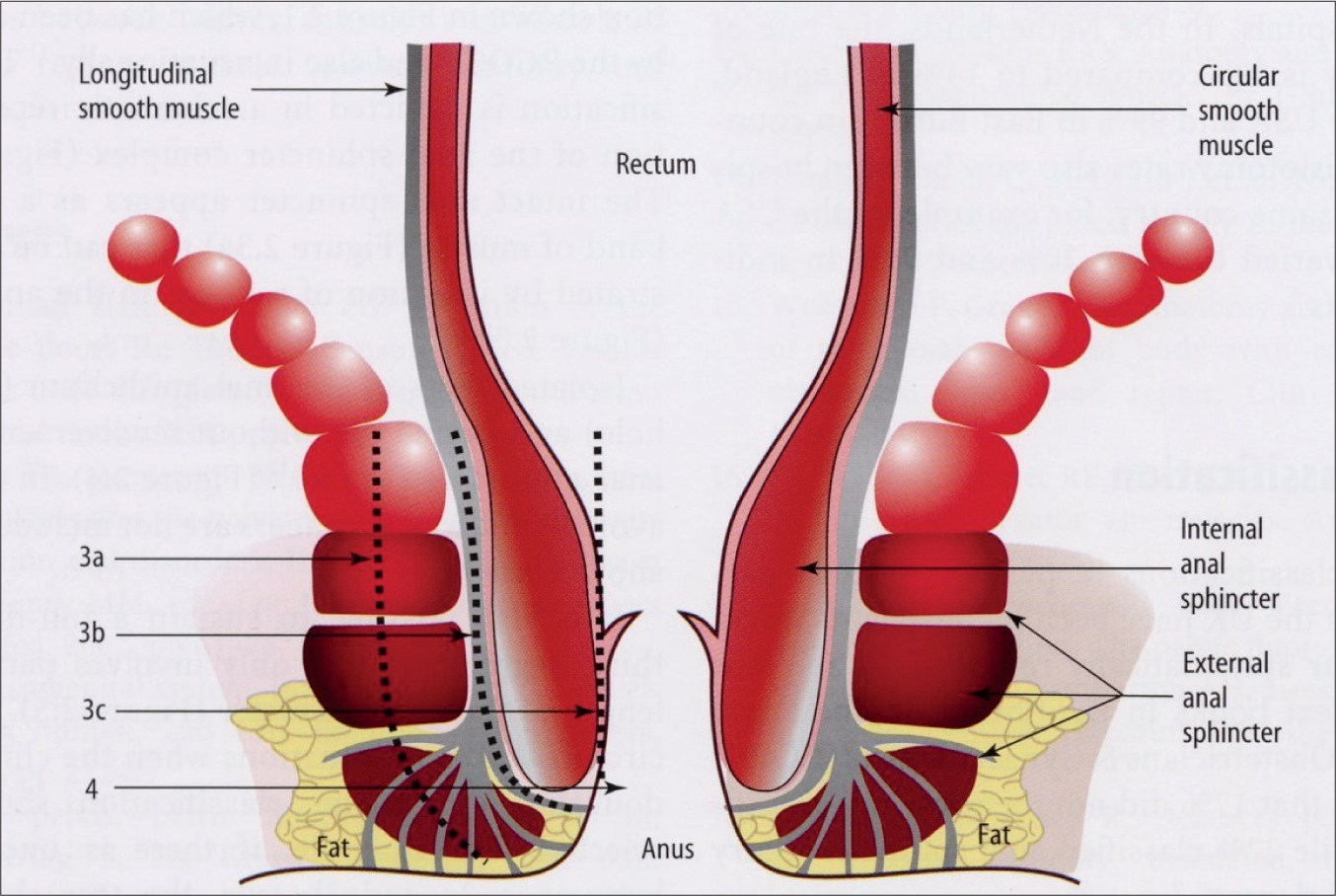

| 3rd degree tear | Injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex |

| Grade 3a tear | Less than 50% of external anal sphincter (EAS) thickness torn |

| Grade 3b tear | More than 50% of EAS thickness torn |

| Grade 3c tear | Both EAS and internal anal sphincter (IAS) torn |

| 4th degree tear | Injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (EAS and IAS) and anorectal mucosa |

| Isolated rectal button hole tear | Isolated rectal and vaginal tear with intact EAS and IAS |

Even with experience and training, studies comparing endoanal ultrasound findings to clinical findings by the accoucheur and an experienced research fellow, have demonstrated that it is possible to misdiagnose or incorrectly classify perineal tears (Andrews et al, 2006; Sioutis et al, 2017). Perineal examinations in the postpartum period may be challenging and examination can be limited for many reasons, including pain, bleeding and poor lighting. Rectal examination is often considered invasive and painful, and is therefore omitted by healthcare professionals (Ali-Masri et al, 2018).

In a survey conducted of the members of the American College of Nurse Midwives, only 13.6% responded that they typically perform a digital rectal examination when anal sphincter involvement is suspected (Diko et al, 2019). In the UK, Andrews et al (2006) reported that midwifery colleagues did not routinely perform rectal examinations which was one of the contributing factors to missed OASIs in 87% of patients.

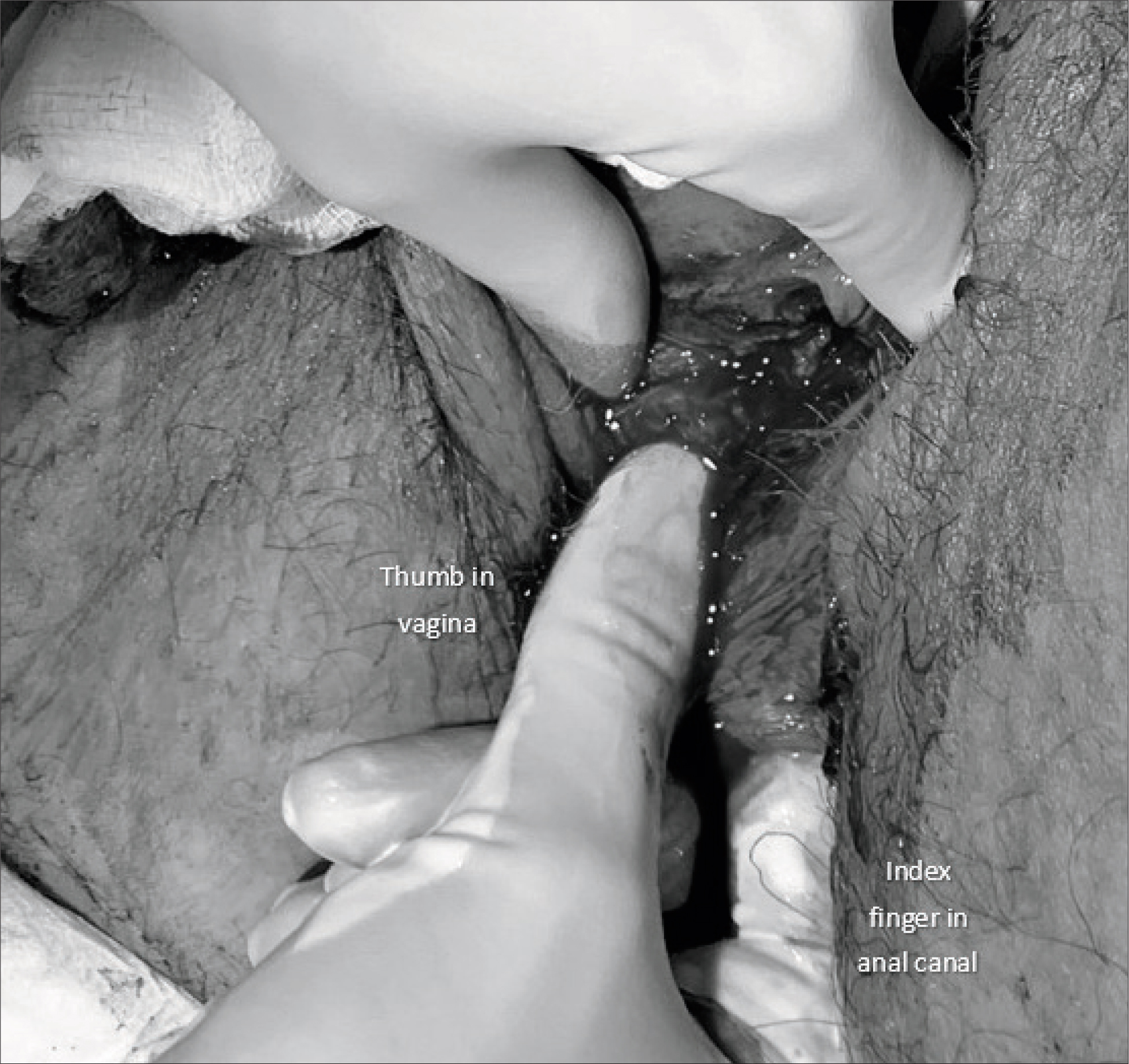

Visual assessment alone of the perineum may not expose the actual extent of the trauma (Wickham, 2012). The guideline published by the RCOG (2015) states: ‘Following vaginal delivery, anal sphincter injury and anorectal mucosal injury cannot be excluded without performing a rectal examination’. This guidance is echoed by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ([ACOG], 2018) and The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) who also recommend that all women should have a systematic vaginal and digital rectal examination following vaginal delivery (Harvey et al, 2015). This should be conducted by a doctor or midwife, trained to diagnose perineal trauma. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence ([NICE], 2017) guidelines on intrapartum care, state ‘if genital trauma is identified after birth, offer further systematic assessment, including a rectal examination’, this excludes deliveries where trauma cannot be seen. Current midwifery textbooks usually advise rectal examination to be included in the assessment, even if the perineum looks intact (Kettle and Raynor, 2009).

It is also important to note the timing of digital rectal examination. NICE and RCOG both recommend conducting a rectal examination before and after suturing perineal tears (RCOG, 2015; NICE, 2017). The rectal examination before repair is performed to classify the tear accurately and after is to check that the repair is complete and ensure that no sutures are penetrating the anorectal mucosa.

Variation in guidance recommendations can lead to differences in practice and it is important for clinicians to be aware of this. There is evidence to show that tears identified at delivery and repaired appropriately have improved patient outcomes compared to when they are missed (Taithongchai et al, 2019).

In this narrative review, the authors aim to review the evidence to support the need to include a digital rectal examination after vaginal delivery to accurately diagnose and classify perineal trauma. The authors describe the anatomy of the anal sphincter, sequalae of severe perineal trauma, medico-legal consequences of missed tears and the importance of training to improve diagnosis of perineal trauma.

Methods

This narrative review summarises studies to evaluate and form conclusions on the need for digital rectal examination after every vaginal delivery. A literature search was performed on 11 September 2019 through the Medline, Cinahl and Emcare databases for articles published from creation of the database to the present day with no language restrictions. The search terms used were ‘digital rectal examination’, ‘obstetrics’, ‘obstetric anal sphincter injuries’, ‘rectal tears’ and ‘vaginal delivery’.

The search returned 74 papers. All titles and abstracts were reviewed, of which 19 relevant papers on diagnosis of OASI and rectal examination after vaginal delivery were included. All study types were included and no tools were used to select papers for inclusion. Papers included were those on missed tears, studies on training and diagnosis of tears, and consequences of OASI.

Knowledge of the perineal anatomy is vital in diagnosis and classification of obstetric perineal trauma. The anal sphincter complex consists of the external anal sphincter (EAS) and internal anal sphincter (IAS). These are separated by the conjoint longitudinal coat. The EAS, which is made of striated muscle has the appearance of red meat. The IAS is made of smooth muscle and appears pale like raw fish meat. The superficial transverse perineal (STP) muscle can be mistaken for the EAS leading to over diagnosis of injury to the EAS (Sioutis et al, 2017). A distinction can be found in the origin of the muscle; where the STP arises laterally from the ischial tuberosity; the EAS surrounds the anal canal. Upward traction on the torn EAS muscle ends would result in lifting the anal canal (Sioutis et al, 2017).

A systematic examination ensures that anal sphincter injury and button hole tears are not missed. This is described in the textbook edited by Sultan and Thakar (2007) ‘Perineal and anal sphincter trauma’. The following steps are advised:

OASI sequelae

Consequences of OASI can be devastating and it is important that healthcare professionals understand this so they can support affected women. While some may experience no symptoms following OASI, others suffer disturbance of bowel function (Sultan et al, 1993), including faecal or flatus incontinence, perineal pain, dyspareunia (Priddis et al, 2014), urinary incontinence (Scheer et al, 2008), and levator ani injury (Volløyhaug et al, 2019). They are also at risk of developing pelvic organ prolapse and rectovaginal fistulae (Sultan et al, 2007). Although rare, the incidence of rectovaginal fistula after fourth degree tear ranges from 0.4%–3% (Combs et al, 1990). Women also experience the psychosocial impact of the stigma and embarrassment associated with resulting symptoms of OASIs (Priddis et al, 2014).

Sultan and Thakar found that the mean prevalence of anal incontinence after primary repair of OASI was 39% (range 15%–61%) (Sultan and Thakar, 2007). Roos et al (2010) found that 39% of 531 women suffered with defecatory symptoms (anal incontinence and/or faecal urgency). Overall, 5% of women suffered with faecal incontinence. Those with major tears (grade 3c or 4th degree) were more likely to suffer faecal urgency, flatus incontinence or liquid faecal incontinence.

When quality of life (QoL) in women with OASI was assessed by Reid et al (2014), three years from primary repair, patients who were identified by endoanal ultrasound to have persistent sphincter defects had no significant improvement in most aspects of QoL. This highlights the importance of accurate primary repair.

Missed OASIs

There are two types of missed tears; one where the tear is missed completely and recorded as a first or second degree tear, and the other where it is under-classified. Both of these can impact a clinical outcome.

It was initially assumed that anal sphincter defects seen only on ultrasound after delivery were ‘occult’ as they were not identified clinically (Sultan et al, 1993). However, it was subsequently shown that occult injuries probably do not exist and the defects previously believed to be occult were actually missed OASIs. In a prospective interventional study when women were re-examined, after the accoucheur (doctors and midwives), by an experienced research fellow, following vaginal delivery, there was a significant increase in identification of OASI (Andrews et al, 2006). Registrars, senior house officers and midwives missed OASIs in 14%, 67% and 87% of patients respectively (Andrews et al, 2006).

An OASI that is not diagnosed at the time of injury can have a devastating impact on a woman's physical and emotional recovery (Taithongchai et al, 2019). It is therefore important that accurate diagnosis and immediate repair is performed to minimise the risk of developing anal incontinence (Andrews et al, 2013). In a matched retrospective cohort study, Taithongchai et al (2019) found that the modified St Mark's score (used to quantify anal incontinence symptoms) was significantly higher in women with missed OASI when compared to OASI that had been diagnosed and repaired at the time of delivery. One in four of missed OASI (22.5% vs 7.5%, p=0.04) required further surgery, with secondary sphincter repair, and one requiring perineal reconstruction.

These findings were corroborated by Ramage et al (2018) in a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients attending a tertiary pelvic floor service clinic. Outcomes from patients with missed OASI were compared to matched patients with OASI that were repaired after delivery. It was found that there were worse short-term outcomes, including faecal incontinence as well as overall physical functioning in women where an OASI was missed at the time of delivery.

These studies highlight the importance of accurate diagnosis of perineal trauma. It is imperative that all professionals involved in immediate postnatal care are adequately trained to diagnose perineal trauma to ensure severe tears are identified and effectively repaired to minimise morbidity.

A quality improvement study in Palestine showed that after a period of focused education and training, OASI rates in primiparous women increased significantly (0.5% vs 3.1%, P<0.001) (Ali-Masri et al, 2018). This was attributed to improve recognition and accuracy in diagnosis by introducing a standardised classification system, confirming the importance of rectal examination. It was estimated that up to 2.8% of OASIs were being missed (Ali-Masri et al, 2018). This confirms the importance of adequately trained healthcare professionals performing assessment after delivery.

In a national practice survey conducted in 2002, 33% of consultant obstetricians incorrectly classified a tear in the anal sphincter as a second-degree tear. This was attributed to confusion with the available classification and under-recognition of OASIs attributed to a deficiency in training (Fernando et al, 2002). Sultan et al (1995) also found a lack of knowledge of anatomy led to misdiagnosis of perineal trauma by midwives and doctors.

Implications of over diagnosis of OASI

A tear that is incorrectly labelled as OASI could have a negative impact on a woman's psychological wellbeing. Sioutis et al (2017) analysed 908 endoanal scan images of women who had sustained OASIs between 2003–2013 attending the perineal clinic. They found that 7% of women were wrongly diagnosed with OASIs when, in fact, they had sustained a second-degree tear.

For these women, although physical symptoms may be not be as severe, the mental and social implications can remain. A woman who believes she had previously sustained an OASI may also use this information to decide about mode of delivery for a future pregnancy. Clinicians may also recommend a caesarean section based on this misconception (Scheer et al, 2009; Jordan et al, 2018). It is possible that anxiety about the implications of a missed OASIS could lead to overdiagnosis (Sioutis et al, 2017). This, again, highlights the importance of training, and regular updates, for all healthcare professionals assessing perineal trauma.

A rectal button hole tear is an isolated tear of the anorectal mucosa and vagina without involvement of the anal sphincters and may present with an intact perineum making them particularly difficult to diagnose (Sultan and Kettle, 2007). These tears are not part of the original, well-known classification as the anal sphincters are not torn (RCOG, 2015). It is, by definition, not a fourth-degree tear and should not be labelled as such. A rectal button hole tear is rare and the true incidence has not been reported but it is estimated to occur in 1: 10 000 vaginal deliveries (Vergers-Spooren and de Leeuw, 2011). Without a digital rectal examination, anorectal mucosal injury cannot be excluded (RCOG, 2015). If it is unrecognised, and therefore unrepaired, it can lead to the development of a rectovaginal fistula. A fistula will lead to passive incontinence of flatus and faeces which are devastating symptoms for a woman to have (Simhan et al, 2004). Rectovaginal fistulae can be difficult to repair and may result in the need for a stoma to defunction the bowel for healing.

Training in diagnosis of perineal trauma

The ‘Standards of proficiency for midwives’, from the NMC (2019), simply state that midwives must demonstrate, at qualification, the skill to ‘undertake repair of first- and second-degree perineal tears and refer additional trauma’. This clearly requires an understanding and ability to diagnose and classify trauma which is not possible without understanding the anatomy and performing a systematic perineal examination after a vaginal delivery.

Surveys of midwives have demonstrated dissatisfaction with their training in assessment of perineal trauma. A questionnaire-based survey completed in two district general hospitals in the UK, showed that more than 90% of midwives felt inadequately prepared to assess perineal trauma. Only 18% in one hospital and less than 30% in the second hospital routinely performed rectal examinations as recommended (Mutema, 2007). In a survey of American nurse-midwives, 63% of respondents said their ability to identify third-degree tears was ‘good’ or ‘excellent’, and 66% correctly identified a standard image of a third-degree tear. However, one-third incorrectly identified this a fourth-degree injury (Diko et al, 2020). Although this survey was conducted in America, this highlights the need for further education for midwives to improve accuracy of identification of perineal trauma.

It appears that accuracy in diagnosis of tears increases with experience and training. When a trained clinical research fellow re-examined 241 women after delivery to confirm perineal injury, the incidence of OASI increased significantly from 11%–24.5% (Andrews et al, 2006). Groom and Paterson-Brown (2002) also found that during a period of increased vigilance, by performing a second examination at delivery in women who sustained any perineal trauma, the third-degree tear rate doubled with a second examination.

Other studies have also found a significant increase in diagnosis of OASI following a period of increased vigilance or training (Ali-Masri et al, 2018). Cornell et al (2016) also found that introducing a new guideline and operative proforma for OASI significantly increased the detection rate (1.6% vs 3.1%). They also found that there was a reduction in detection of rectal button hole tears (4% vs 0%). In both of these studies, the changes in rates of OASI were attributed to improved education and awareness (Cornell et al, 2016; Ali-Masri et al, 2018).

Education in diagnosis and repair of perineal trauma is difficult to obtain in real-life situations on labour ward. Training courses which include theoretical lectures and simulation models have therefore been suggested as an adjunct (but not replacement). To improve training, Sultan and Thakar have introduced a course using diadatic lectures, video demonstrations and a pig anal sphincter model (Croydon Urogynaecology and Pelvic Floor Reconstruction Unit, 2020). Evaluation of the course using questionnaires demonstrated that knowledge of identification and repair techniques for OASI, of doctors and midwives, changed after attending a one-day, hands-on workshop. There was a significant increase in attendees who converted to performing a rectal examination prior to repair of perineal trauma (Andrews et al, 2005).

Many national guidelines globally state that relevant healthcare professionals should attend specialist training in perineal assessment and repair in order to increase detection rates of OASI (Tsakiridis et al, 2018). Current midwifery standards need to have a more focused approach to diagnosis of perineal trauma and highlight the importance of diagnosis of perineal trauma.

Medico legal consequences of OASIs

Missed OASI not only has implications for the woman, but can also lead to litigation. In 2012, the NHS Litigation Authority in the UK reported ‘10 years of maternity claims’. This described perineal trauma as the fourth most common indication for claims made in obstetrics (Anderson, 2013). According to the RCOG guidelines (2015), the occurrence of an OASI during a vaginal delivery is not usually considered substandard care; however, failure to recognise OASI or to repair it adequately may be considered substandard care (Wickham, 2012).

Interestingly, a claim (Starkey vs Rotheram NHS Trust, 2007), before the RCOG guidelines were released, failed because it was deemed that it would not have been part of routine care to perform a digital rectal examination prior to the guidelines stating this. The mother had given birth in 2000 by a forceps delivery; at the time no OASI was identified. She was subsequently diagnosed with OASI. However, because the guidance on detecting OASI was released in 2001, it was deemed not negligent to have not identified the tear (Symon, 2008).

All clinicians should be aware of current guidelines and ensure training is up-to-date to avoid a tear being misdiagnosed, leading to increased morbidity and litigation.

Recommendations

In conclusion, midwives are often the sole carers for women during delivery and postnatally. Their ability to diagnose and classify perineal trauma is an essential skill. A structured, digital rectal examination is vital to prevent missing OASI and isolated rectal injuries. If these injuries are missed, it will lead to worse outcomes for the woman and they may require further surgery and intervention. Litigation is common in this area of obstetrics and a missed tear is considered negligent.

Over diagnosis of OASIs may occur and can influence decisions for future deliveries. It is crucial that healthcare professionals who are responsible for diagnosis and classification of perineal trauma are adequately trained to do so. We recommend that all healthcare professionals who may be involved in diagnosis and/or repair of perineal trauma attend appropriate training courses regularly to improve competence. However, the need to return to basics of performing a structured vaginal and rectal examination after every vaginal delivery cannot be overemphasised.