Many midwives would agree that the priorities in maternity care mostly centre around intrapartum and antenatal care, and that postnatal care has long been the ‘Cinderella’ of the maternity service (Drife, 1995). However, due to a rising prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in the UK (Taylor et al, 1984; Gupta et al, 2004), parents may be concerned about infant dry skin and midwives may be regularly asked how to treat it. Skincare advice given to parents by health professionals may be contributing to the increase in childhood atopic eczema due to the uncertainty about evidence-based practices (Cooke et al, 2018). In view of the potential effects of using harmful treatments for infant dry skin on the development of childhood atopic eczema, it is important that health professionals who provide this information only recommend treatments that are safe, as shown by robust evidence.

The process of adaptation to the extra-uterine environment following birth may trigger neonatal dry skin following a stage of ‘drying out’ from the conditions of immersion in wet amniotic fluid in utero. Indeed, trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) has been shown to be high in the first few hours after birth (Rutter and Hull, 1979). A high rate of TEWL continues throughout the first year (Nikolovski et al, 2008) and dry skin may persist during the initial months of an infant's life (Saijo and Tagami, 1991). This is an entirely normal and expected process that would not usually require treatment.

Infant skin

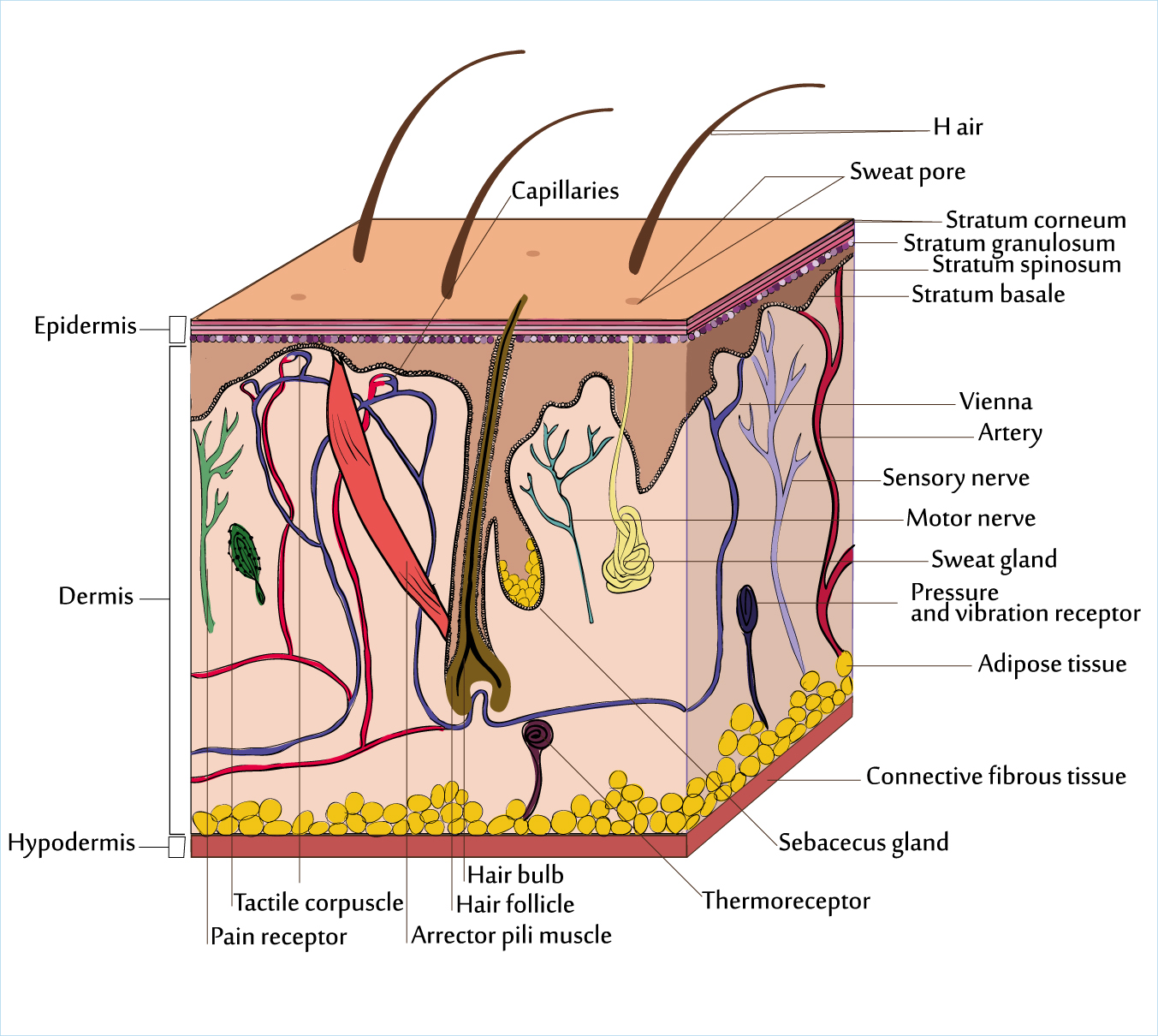

Human skin separates and protects the body's internal organs from the environment, preventing infiltration from external irritants, allergens and pathogens, and excessive water loss (Lewis-Jones, 2012). The skin comprises three layers: the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis (Figure 1). The epidermis is the outer layer, consisting of layers of tightly packed keratinocytes, with the stratum corneum being the uppermost, visible part of the skin. New keratinocytes are formed in the stratum basale, travelling upwards through the skin layers until they become corneocytes as they traverse the stratum compactum (Candi et al, 2005). Once the corneocytes reach the surface of the skin, they are shed from the stratum corneum (desquamation). Desquamation is a normal body process and this shedding is rarely visible.

There are some important differences in biological composition between infant and adult skin that prompt a need for special care of infant skin. Infant skin continues to develop throughout the early years of life (Nikolovski et al, 2008; Fluhr et al, 2011; Stamatas et al, 2011). Infant skin is susceptible to increased permeability and dryness as the epidermis is 20% thinner and stratum corneum is 30% thinner, compared to adults (Stamatas et al, 2010). Furthermore, as the ratio of body surface to body weight is higher for infants than for adults, topical agents can increase vulnerability due to the possibility of greater absorption (Nikolovski et al, 2008).

Skin barrier function can be affected by genetic and/or environmental factors. The skin barrier can be visualised as a brick wall (Elias, 1983): the ‘bricks’ represent the corneocytes, and these corneocytes are surrounded by lipid lamellae, represented by the ‘mortar’. Good skin barrier function, where water loss is minimised and external agents cannot penetrate, is enabled by a strong wall with no cracks or fissures in the mortar. However, in a broken wall with crumbling or cracked mortar, TEWL and penetration by external bacteria, irritants and allergens is enabled, stemming from a less ordered, more fluid-like structure of the lipid lamellae. Infant skin also comprises fewer lipids, and less melanin and natural moisturising factors compared to adults (Chiou and Blume-Peytavi, 2004; Nakagawa et al, 2004), resulting in a propensity to increased TEWL and reduced stratum corneum hydration; established indicators of less effective skin barrier function.

Dry skin is described as ‘a cutaneous reaction pattern reflecting abnormal desquamation of diverse [a]etiologies’ (Madison 2003: 236). In normal skin, corneocytes are shed from the surface of the skin (desquamation) in such small quantities that they are not usually visible. In dry skin, the skin appearance becomes rough and flaky as this process is disturbed—it is this visible ‘shedding’ of skin that prompts parental concern. Health professionals in the position to address these concerns commonly recommend the use of topical oils for the prevention and treatment of infant dry skin (Walker et al, 2005; Cooke et al, 2011). This guidance may have arisen from the fallacy that ‘natural’ topical agents must also be ‘safe’ (Lavender et al, 2009; Bedwell and Lavender 2012), which has resulted in the widespread use of untested vegetable oils on newborn skin.

Routinely recommended treatments

Topical skincare products are applied on to the surface of the skin, and the use of topical oils for care of the skin can be documented as early as 2760BC (Mitzel-Wilkinson, 2000). Mustard and coconut oils are routinely used in Eastern cultures (Darmstadt and Saha, 2002; Mullany et al, 2005; Sankaranarayanan et al, 2005), but in the UK, olive oil and sunflower oil have been the most commonly recommended (Cooke et al, 2011). The early use of particular types and formulations of oils for the prevention or treatment of infant dry skin may negatively affect skin barrier function (Cooke et al, 2016) and may consequently contribute to the development of childhood atopic eczema (Danby et al, 2013).

Atopic eczema is a disease characterised by dry, scaly, red, blistered and itchy skin resulting from the breakdown of the skin barrier, cutaneous inflammation and allergy (Bieber 2008; Danby and Cork, 2011). Approximately 60% of cases are diagnosed in the first year after birth, with 45% in the first 6 months (Bieber, 2008). Estimates indicate a UK prevalence for children aged 2–15 years of more than 20% (Flohr and Mann, 2014), an increase from approximately 5% in the 1940s (Taylor et al, 1984) that cannot be attributed solely to genetic pre-disposition where an infant has a family history of atopic eczema.

Over past decades, the way that we care for infant skin has changed dramatically, influenced by a variety of environmental factors, including the easily accessible increase in options and parental choice for infant skincare in terms of products, detergents and oils (Cork et al, 2009; Danby and Cork, 2011). Only topical products that have been tested in clinical trials and shown to have beneficial effects on the skin barrier should be used on newborn infants. A plethora of research is available which has shown that certain compositions of oil can affect the stratum corneum: olive oil, for example, with a high ratio of oleic acid to linoleic acid, disrupts the lipid structure of the skin barrier in all tested populations (Darmstadt et al, 2002; Jiang and Zhou, 2003; Danby et al, 2013; Cooke et al, 2016). Sunflower oil, with a high ratio of linoleic acid to oleic acid, has been shown in some studies involving adults and mice to benefit the skin barrier (Darmstadt et al, 2002; Danby et al, 2013); however, in two studies assessing the impact of sunflower oil on infant skin, the development of the skin barrier was delayed in the oil group compared to the control group using no oil (preterm infants: Kanti et al, 2014; term infants: Cooke et al, 2016). To date, it is not proven whether there is a link between the use of topical products on newborn skin and the development of childhood atopic eczema, but the potential for this link does exist.

Clinical practice

It has been shown that infants are susceptible to reduced skin barrier function. It has also been shown that some topical products have an adverse effect on skin barrier function. For midwives and any other health professionals giving advice on infant skincare, clinical recommendations should be underpinned by evidence, preferably in the form of randomised controlled trials. Most importantly, clinical advice and recommendations should safeguard infant skin by only suggesting the use of topical products which have been proven to exclude any possible adverse effect or alteration to infant skin barrier.

Atopic eczema is diagnosed in the first 6 months of life in 45% of cases (Bieber, 2008), a period of time when midwives and other maternity health professionals have the most potential to influence parental practices. Parents want to use skincare products on their infants, but there is a lack of evidence-based guidance for health professionals on infant skincare (Lavender et al, 2009; Furber et al, 2012; Cooke et al, 2018). Without this knowledge, uncertainty or reliance on tradition or personal experience may mean that advice may be doing more harm than good.

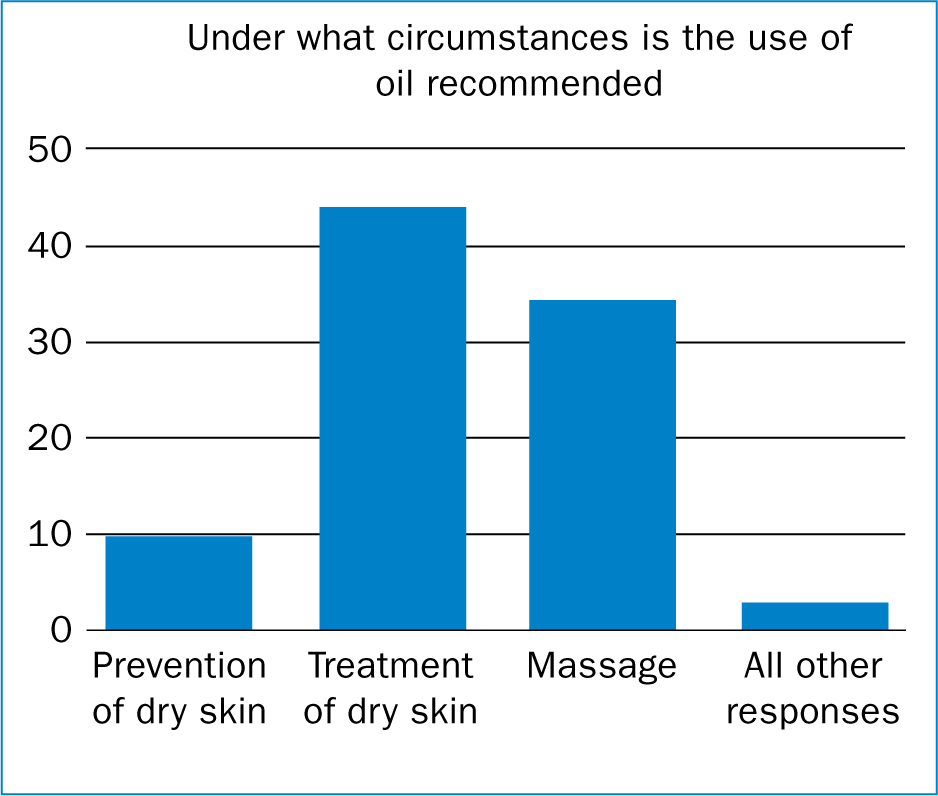

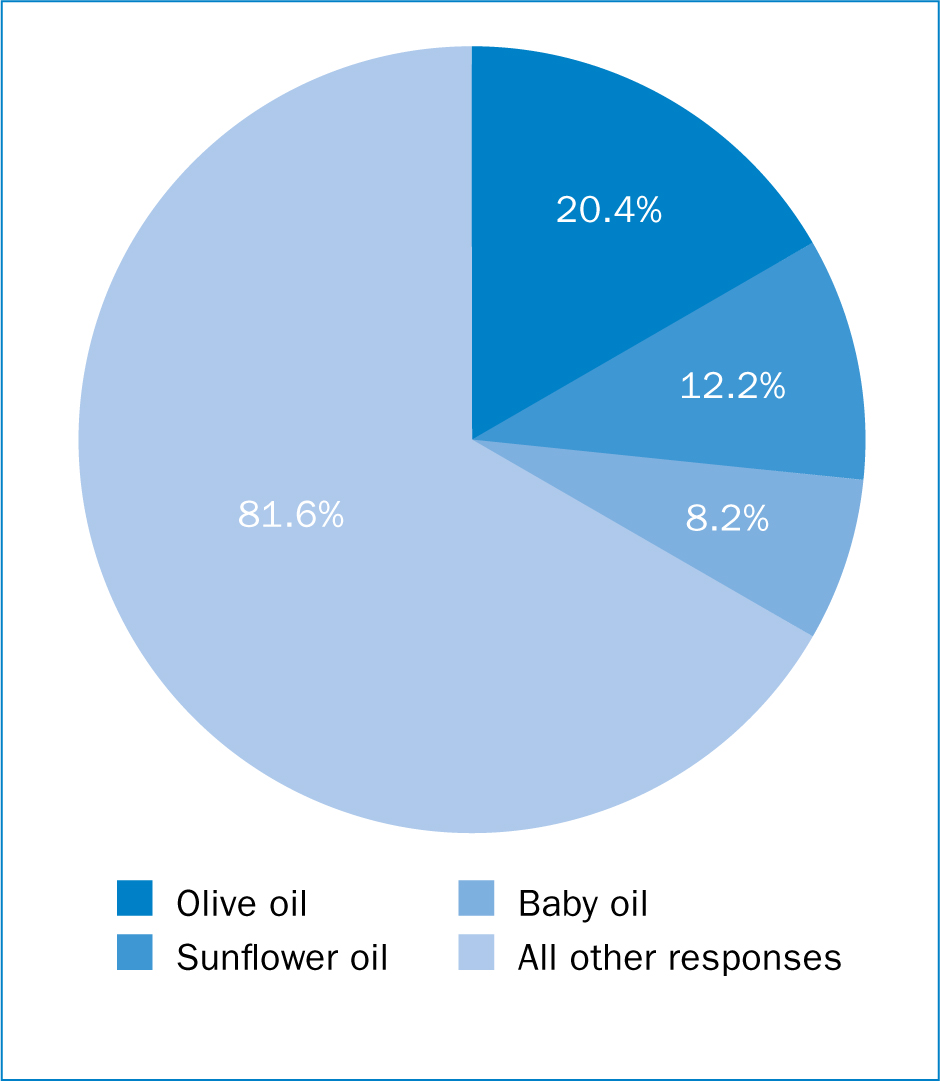

The recommendation to use topical oils for the treatment of infant dry skin (Figure 2)—most commonly olive oil (Figure 3)—has become traditional practice (Walker et al, 2005; Cooke et al, 2011). A survey of maternity units in the North West of England with an 80% response rate (Walker et al, 2005) found that 17 different infant skincare products were recommended to parents by health professionals. Olive oil was recommended by 75% of respondents, closely followed by commercial baby oil (71.4%). In a more recent online national survey of UK maternity and neonatal units (Cooke et al, 2011), the advice on olive oil had not changed. The aim of this more recent survey was to establish what oils were used or recommended to parents by UK maternity service health professionals, and for what reasons. This survey had a lower overall response rate (31%) than the study by Walker et al (2005), but was within the expected range for online surveys (Hamilton, 2009). The survey found that 52% of responding units recommended the use of topical oil mainly to treat dry skin (Figure 2). Of those, 81.6% recommended olive oil and 20.4% recommended sunflower oil (Figure 3), highlighting that olive oil was still the routine recommendation for infant dry skin amongst maternity health professionals nationally. However, unlike the earlier survey (Walker et al, 2005), commercial baby oil was not recommended as frequently (12.2%). There is no obvious reason for this difference, but possibly midwives have become more research-aware in recent years, and are reluctant to recommend commercial products for which there is no evidence base. There is a dearth of evidence to support recommending vegetable oils; however, societal interest in ‘natural’ products has increased (Allemann and Baumann, 2009), and this is evident for parents of newborn infants (Cottingham and Winkler, 2007).

Parents want to use skincare products to make their infant look and smell nice (Lavender et al, 2009; Furber et al, 2012), and can become anxious about any adverse condition of their infant's skin (Adalat et al, 2007), often heeding advice provided by health professionals regarding their infant's care (Lavender et al, 2009). It is concerning that the use of topical oils for infant skincare is still recommended by maternity workers, is not regulated, and could be harmful. Awareness of the evidence base and an update of national and local clinical guidelines is needed so that health professionals can offer the best advice for infant skincare and avoid harmful practices.

Evidence to support clinical practice

A systematic review of the evidence for healthy term infant skincare has recently become available (Cooke et al, 2018), and this can assist health professionals to support informed decision-making and choice for women and their families about infant skincare. The review focused on normal aspects of care, including bathing and cleansing, nappy care, care of the hair and the scalp, management of dry skin, and oils used for infant massage. The age range for the review was birth to 6 months to encompass any evidence on prevention of atopic eczema, usually diagnosed at the earliest around 6 months of age (Wadonda-Kabondo et al, 2003). Systematic reviews sit at the top of the hierarchy of evidence (Guyatt et al, 1995; Evans, 2003), as they have the potential to provide increased reliability and generalisability, together with increased power and precision of findings due to the pooling of data from multiple studies (Akobeng, 2005).

The systematic review (Cooke et al, 2018) found strong evidence to avoid recommendation of olive oil or sunflower oil for the management of dry skin in healthy term infants, and a spread of strong to weak evidence supporting the use of daily emollient therapy to prevent atopic eczema in high risk infants (those with a genetic pre-disposition to atopic eczema). In addition, the results from two studies published since the systematic review should be considered (Kanti et al, 2017; Yonezawa et al, 2018), but with caution, due to the method in which the interventions were tested. One study found that moisturising care (defined as reduced frequency of bathing and daily moisturiser application) could improve skin barrier function and prevent dry skin (Yonezawa et al, 2018); however, it was not possible to separate the individual effects on the skin pertaining to the reduction in bathing or to the application of the moisturiser. Dry skin was assessed at 3 months old and a previous study found that normal neonatal dry skin due to transition from birth was improved by 28 days old in most infants (Cooke et al, 2016). The second study found that the use of sunflower seed oil or baby lotion did not harm skin barrier adaptation (Kanti et al, 2017); however, this was an unpowered study (n=46) with no control group with which to compare normal skin barrier development, so it was not possible to assess whether skin barrier development could have been impeded by use of either or both of these interventions. In support of this point, a previous study (Cooke et al, 2016) found that development of the skin barrier was impeded in each oil comparison with the control group (no oil), but when each oil was compared with the other oil, no difference in skin barrier maturation could be detected, as both oils had a similar effect.

Evidence-based management

Professional consensus and evidence suggests that clinical advice and recommendations for the management of healthy term infant dry skin should encompass:

There is a need to increase awareness of the evidence to enable health professionals to confidently give evidence-based advice and promote parental informed choice. National clinical guidelines need to be updated to include the most contemporary evidence. The UK postnatal care guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2014) have only one standard (Box 1) for infant skincare. This standard promotes advice that is not evidence-based and does not address management of dry skin. The guideline has been updated in some areas since 2006, but not for infant skincare. Since 2006, there have been several clinical trials and other studies related to dry skin and atopic eczema which have not been included in this guideline (Garcia-Bartels et al, 2010, 2011; Lowe et al, 2012; Simpson et al, 2010; 2014; Horimukai et al, 2014; Kvenshagen et al, 2014; Cooke et al, 2016; Kanti et al, 2017; Yonezawa et al, 2018). The infant skincare systematic review (Cooke et al, 2018) supports the development of new clinical guidelines, which could also incorporate advice from the European roundtable meeting for infant skincare (Blume-Peytavi et al, 2016) and the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) neonatal skincare guidelines (AWHONN, 2013), particularly where empirical evidence is not available. A UK national audit has confirmed that very few maternity units have an infant skincare policy (Personal communication, 6 January). When combined with outdated national guidelines, it is unsurprising that health professionals are uncertain about safe and effective infant skincare practices, which can result in advice based on traditional practice and personal experience.

There is an urgent need for education and training to be developed which should encompass increasing knowledge of the evidence base, understanding the application of evidence to best clinical practice, and increasing the awareness of the potential impact of particular products on the development of atopic eczema. This needs to be reflected in infant skincare policies in individual maternity units. As the same products frequently recommended for treatment of infant dry skin are routinely used for infant massage, so there is also an urgent need for clear guidelines for infant massage to prevent the use of inappropriate massage lubricants that may affect skin barrier function, as this practice is becoming increasingly popular in the UK.

Conclusions

Appropriate skincare advice for the management of infant dry skin is essential to protect skin barrier function and development, and prevent any potential contribution to development of childhood atopic eczema. Even with the evidence available to health professionals, there are still uncertainties: for example, we know that parents want to treat infant dry skin but, as yet, there is no treatment that has been tested and proven to be safe. However, what is certain is that midwives should only give advice that cannot harm the infants in their care.

It is possible that the use of inappropriately formulated or natural products may be a contributory factor in the development of childhood atopic eczema. Clinical recommendations to parents should include information that no untested vegetable oil, including olive oil or sunflower oil, should be used and that infant dry skin in the first 3-4 weeks following birth is a normal process of adaptation to extra-uterine life and should resolve without treatment. Until further research is available, caution is required in the advice given to parents for management of infant dry skin.