Breastfeeding rates in the UK remain some of the lowest in the world. The World Health Organization (2020) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of an infant's life, followed by breastfeeding along with appropriate complementary foods up to two years of age or beyond. However, the last UK-wide infant feeding survey reported that exclusive breastfeeding rates declined from 81% to less than 25% by six weeks postpartum (IFF Research, 2013).

The reasons for premature discontinuation of breastfeeding are complex and varied at what is a highly emotive time in a new mother's life. Nipple soreness and pain are common challenges a new mother faces when establishing breastfeeding and are frequently cited as reasons for cessation of breastfeeding earlier than intended (Morland-Schultz and Hill, 2005; Dennis et al, 2014). Nipple pain is often attributed to suboptimal positioning and attachment of the infant (Righard, 1998; Kent et al, 2015). Other common causes relate to maternal or infant physiology eg flat or inverted nipples, infant ankyloglossia/palatal anomaly or underlying infection (L'Esperance, 1980; Snyder, 1997; Messner et al, 2000; Tait, 2000; Walker, 2008; Amir et al, 2013).

However, in many cases, nipple soreness, damage and pain are experienced in the absence of a clear underlying cause. Most frequently, this occurs in the early days as breastfeeding is established and resolves as both the mother and infant's experience increases. This may in part be due to the infant's sucking action creating a vacuum which causes physical friction on the nipple, leading to tissue damage and subsequent pain (Tait, 2000; McClellan et al, 2008; Walker, 2008; Perrella et al, 2015). For the purposes of this study, the authors will refer to nipple pain with no clear underlying physiological cause as latch-related nipple pain (LRNP).

Various tools and solutions are used to help mothers experiencing nipple damage and pain. There is extensive evidence that education around correct latch and infant positioning leads to a decrease in nipple pain and increased duration of breastfeeding in most cases (Cadwell et al, 2004; Darmangeat, 2011). However, other studies report that education on proper positioning and attachment during the first few days after birth did not result in longer breastfeeding or fewer breastfeeding problems (Labarere, 2003; De Oliveira, 2006; Henderson et al, 2011). This highlights the fact that faulty positioning and attachment is not the only cause of nipple pain (Kent et al, 2015).

Historically, mothers have been advised to rub breastmilk onto sore nipples after feeding; this is thought to aid healing due to its intrinsic immunological properties (Witkowska-Zimny et al, 2019) and is a cost-free tool available to all. A variety of commercial solutions are also utilised to help prevent and manage nipple damage and subsequent pain, including creams, ointments, hydrogel pads and nipple shields. One such product is Highly Purified Anhydrous (HPA®) Lanolin (Lansinoh® Laboratories).

Lanolin is structurally very similar to lipids found within the skin, particularly in the stratum corneum. These lipids contribute to the integrity of the skin barrier (Kligman, 2000). Lanolin is an excellent moisturiser and emollient, forming a stable emulsion with water in the skin to prevent evaporation and retain moisture (Harris, 2000). In addition, several studies have shown that lanolin can improve the healing rate of partial-thickness skin wounds by providing a moist wound-healing environment (Chvapil et al, 1988; Brent et al, 1998; Büyükyavuz et al, 2010). For breastfeeding, these properties mean healthcare providers often recommend the application of lanolin to treat nipple trauma and soothe dry and irritated nipples, especially during the first days of breastfeeding (Jackson and Dennis, 2017). Aside from expressed breastmilk, lanolin is the only intervention that has received continued endorsement by the La Leche League International, the most predominant global community based breastfeeding support network for women. Lanolin is also recommended by the International Board Certified Lactation Consultants and is included in their core curriculum for lactation consultant practice (Mannel et al, 2008; Jackson and Dennis, 2017). Because it is a naturally occurring, non-toxic substance, mothers do not have to worry about incidental ingestion by their infant. Additionally, it is neutral in taste and odour, minimising any effect on the infant's ability or desire to latch and nurse. HPA Lanolin is a highly purified grade of lanolin that goes through a unique and extensive refining process to remove any residual environmental contaminants present in the raw material, therefore ensuring the safety of the product for the specific use on the nipples of breastfeeding mothers (LactMed, 2018).

The objective of this study was to investigate the incidence and causes of nipple pain in breastfeeding mothers, with particular focus on LRNP; nipple pain where there was no clear medical or physiological underlying cause. Additionally, data was collected to understand what advice, assistance and solutions mothers experiencing this issue had sought and how helpful they felt these solutions were in enabling them to breastfeed for longer.

Methods

Data was collected through use of an online survey of UK-based women over a one-month period. Participants had all given birth to their youngest child within the last 24 months, initiated breastfeeding and had completed their breastfeeding journey (n=1084). The survey questions, survey structure and subsequent data analysis and interpretation were derived and performed by the authors. The online survey was hosted by a specialist research agency.

The project utilised quantitative online market research methodologies to ensure that a large enough representative sample could be obtained. Respondents were obtained from a specialist UK young family panel via their standard processes which includes adherence to Market Research Society guidelines and GDPR standards. The provider's panel is made up of predominantly offline-recruited UK pregnant women and mothers who have all given specific consent to join the panel and receive survey invites. Standard demographics were obtained from respondents such as number of children, age, socio-economic group and geographical location, and tested to ensure that the sample was representative of the UK population (within the group that consists of women with young children).

Of the respondents, 1084 said they had breastfed their youngest child at any time and recently completed breastfeeding. It was critical to ensure that the population comprised only of those who said that they had completed breastfeeding to ensure that analysis was being conducted across the entire breastfeeding journey. Inclusion of respondents was based solely on the above criteria. Familiarity with, or awareness of, any particular brand was not part of the screening process and at no point were the respondents aware of who was sponsoring the study.

Breastfeeding duration and impact of combination feeding

Of the 1084 mothers who completed the study, 76% were still breastfeeding at one-month postpartum. The respondents who identified as still breastfeeding at six months was 46%. This had reduced to 15% at 12 months (Table 1). The average breastfeeding journey length was 28 weeks (Table 1) however, within that data point, there were distinct differences between those mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding (average breastfeeding length at 35 weeks) and those who combination fed both breastmilk and formula from the outset (average breastfeeding length at 15 weeks).

| Timeline | All respondents (n=1084) | Respondents who combination fed from birth (n=172) | Respondents who exclusively breastfed (n=480) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Still breastfeeding at 1 month | 76% | 71% | 88% |

| Still breastfeeding at 3 months | 62% | 45% | 77% |

| Still breastfeeding at 6 months | 46% | 23% | 63% |

| Still breastfeeding at 9 months | 28% | 11% | 41% |

| Still breastfeeding after 12 months | 15% | 5% | 26% |

| Average breastfeeding length | 28 weeks | 15 weeks | 35 weeks |

Issues which impact breastfeeding

Of the 1084 women included in the study, 68% reported that they experienced physical issues relating to breastfeeding itself. Of these, 76% experienced LRNP (n=537), 38% experienced engorgement (n=279), 21% experienced mastitis (n=157) and 19% had suffered from blocked ducts (n=143) (Figure 1). Other issues, namely thrush, inverted nipple, milk blister and breast abscess were far less frequent and were experienced by 10% or less of those surveyed.

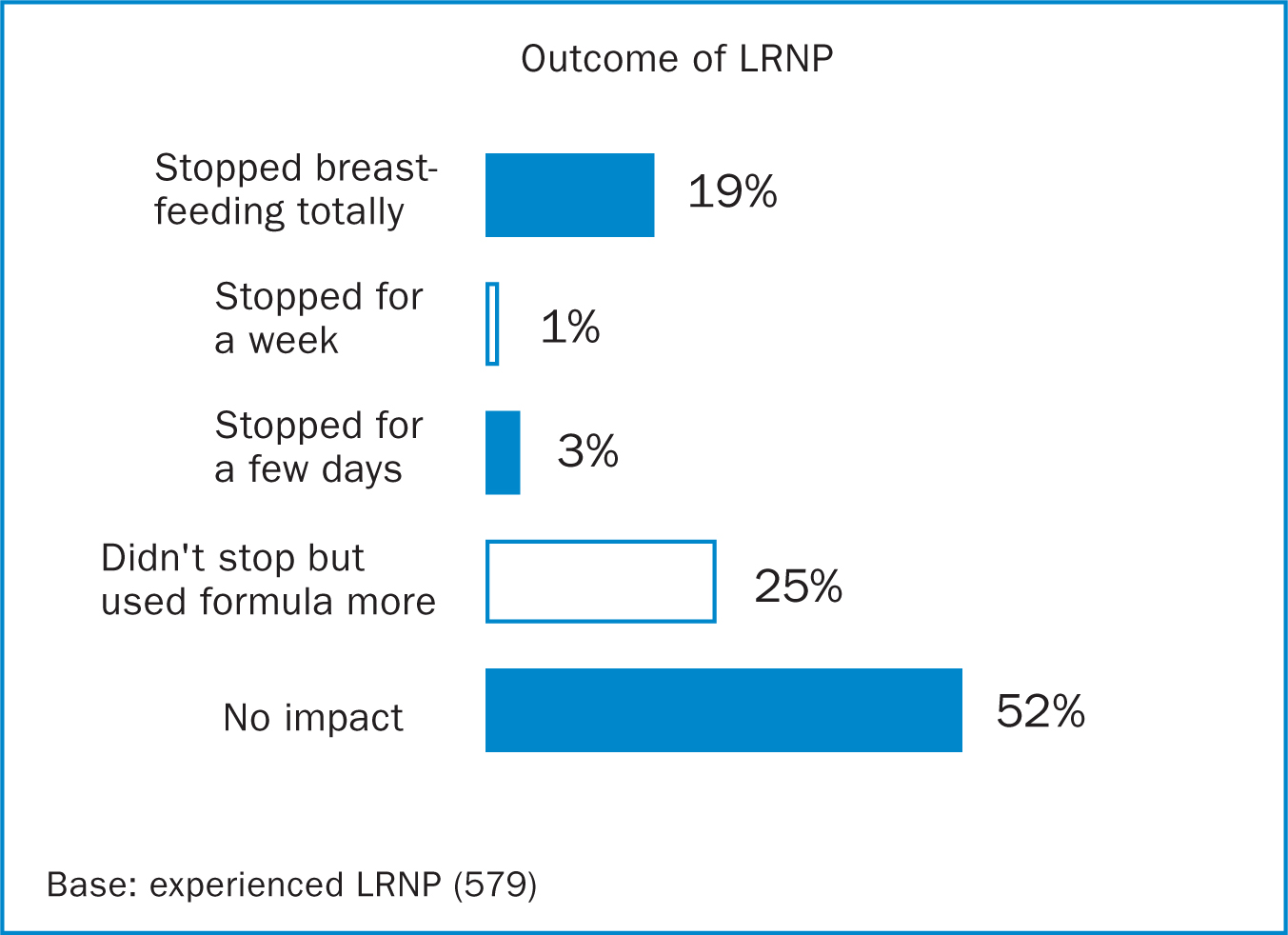

LRNP was found to have a substantial impact on breastfeeding outcome with 19% of those surveyed reporting it led them to stop breastfeeding totally, while a further 29% stopped for a short time and/or increased formula feeds (Figure 2). Of the mothers that stopped breastfeeding due to LRNP, 70% did so within the first month (data not shown). Symptoms associated with LRNP were general nipple tenderness and soreness (96%), cracked nipple (74%), nipple redness (37%), scabbing (36%), exuding/bleeding nipples (33%) and inverted or flattened nipple (11%).

Managing LRNP

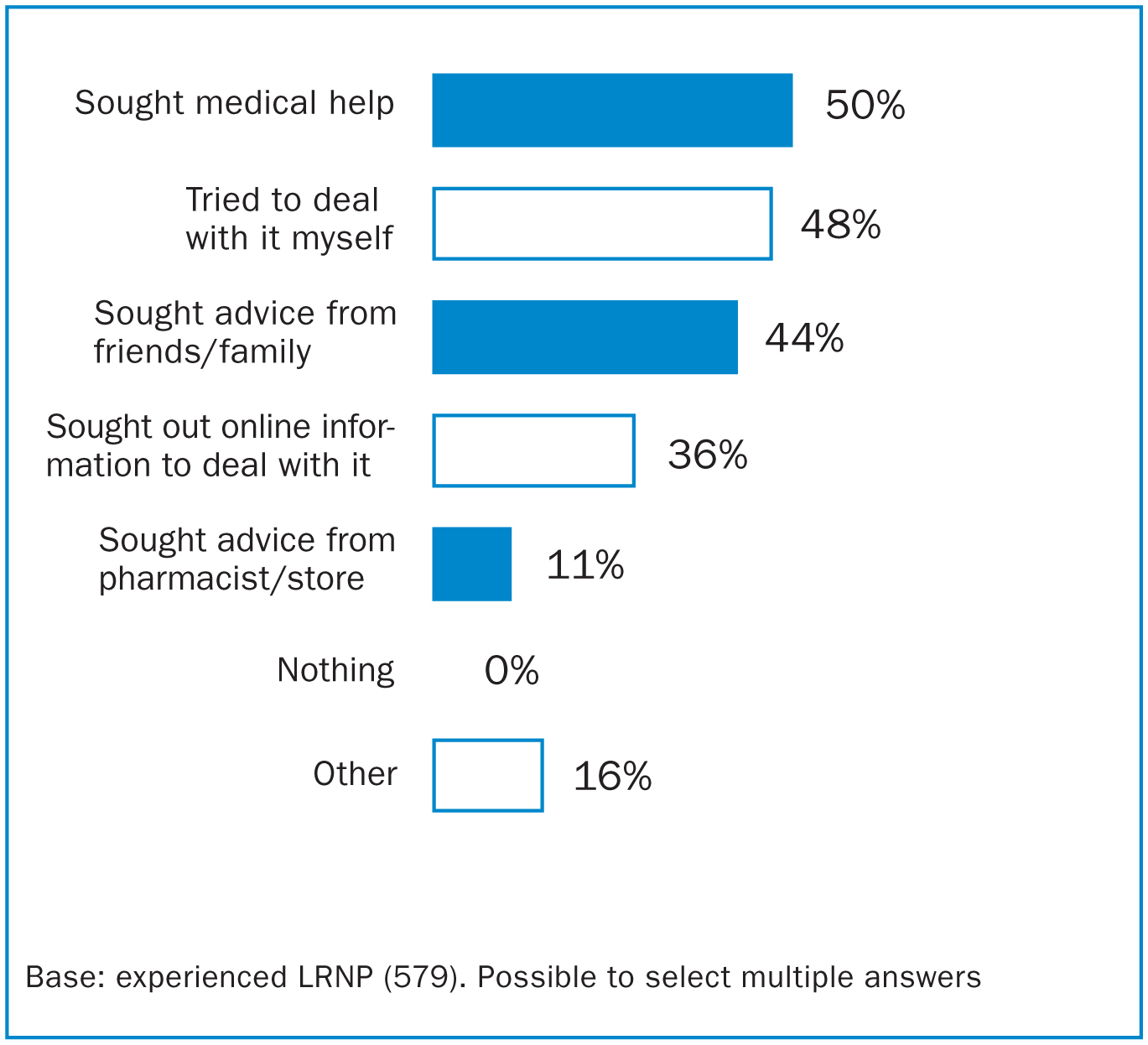

Figures 3 and Figure 4 capture the various things mothers did to try and deal with their LRNP. Help and advice was sought from a variety of sources including friends, family, online sources and healthcare professionals. Although 16% selected ‘other’, the verbatim responses associated with this selection indicated that almost all who selected it used this option to mention seeking help from a specific healthcare professional. The true ‘other’ was only 3% of the total (Figure 3).

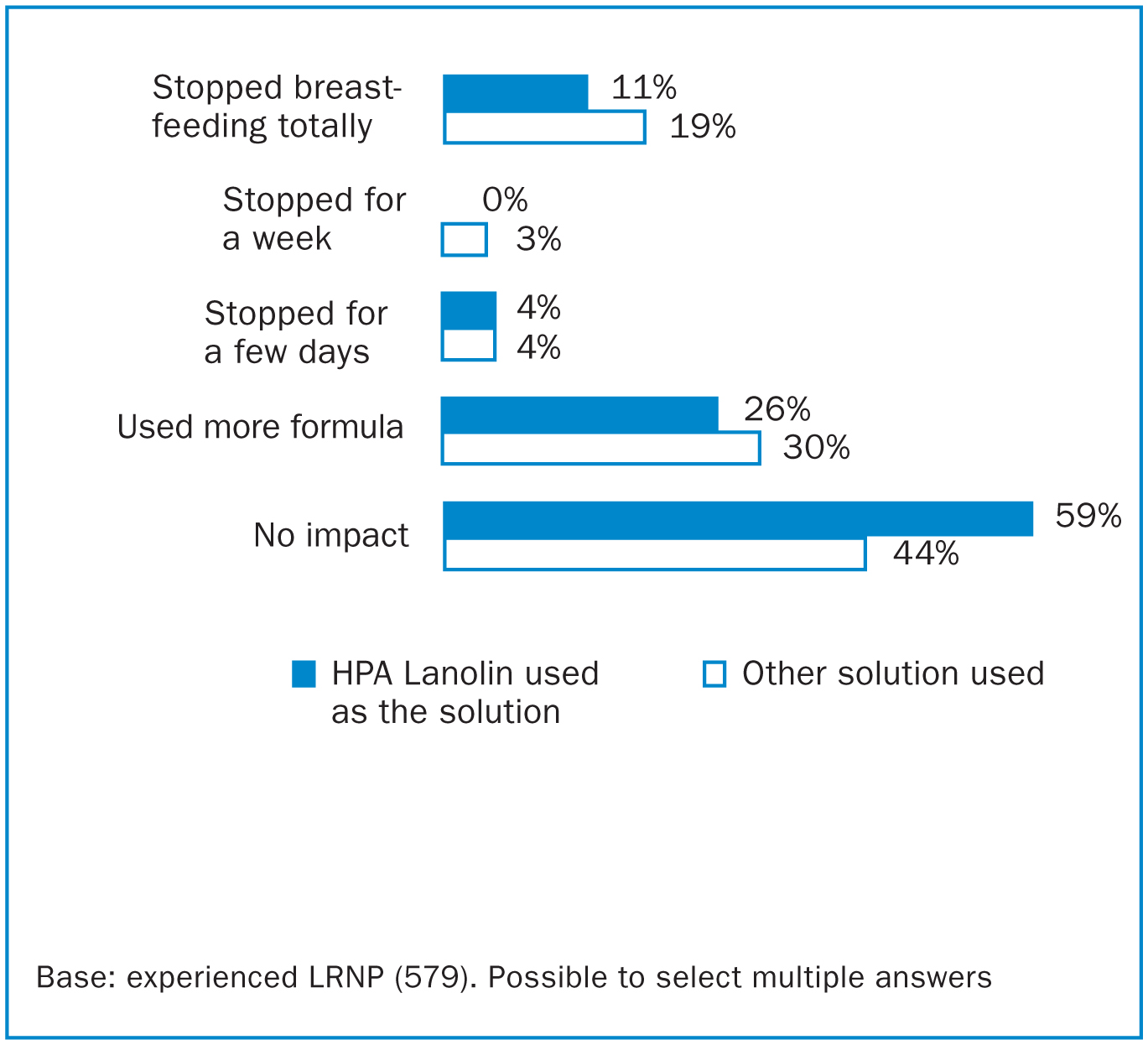

When asked what tools or solutions they used to manage LRNP, respondents had a free text box to provide a response rather than selecting from a multiple-choice list. HPA Lanolin was the most utilised solution (31%), followed by nipple shields (21%) and nipple creams (unspecified type) (20%) (Figure 4). Other solutions used included help with latch and positioning from healthcare professionals, treatments for thrush/mastitis and hydrogel pads. The data was analysed to see whether the choice of solution utilised for LRNP affected the breastfeeding outcome. It was found that the impact of LRNP was considerably less when HPA Lanolin was used as a solution; 11% of those using HPA Lanolin as a solution stopped breastfeeding completely compared to the 19% did not use HPA Lanolin (Figure 5). Additionally, of the mothers who suffered from LRNP but continued to breastfeed with no impact, 59% had used HPA Lanolin as a solution compared to 44% of those who used an alternate solution (Figure 5).

The data was also reviewed to see whether the choice of solution utilised for LRNP had any effect on how long the symptoms relating to LRNP persisted for. It was found that where HPA Lanolin was used as a solution for LRNP, the duration the symptom persisted for was shorter (5.1 weeks versus 7.1 weeks when HPA Lanolin was not a solution) (Table 2). When broken down by individual symptoms associated with LRNP, the duration each symptom was experienced for was consistently shortened for those using HPA Lanolin as a solution. Significantly, a difference was also seen for the total duration of breastfeeding achieved by mothers who suffered from LRNP, depending on the solution used. Mothers that utilised HPA Lanolin as their solution breastfed for longer; the average breastfeeding duration was 33.2 weeks for those who used HPA Lanolin compared to an average duration of 26.5 weeks for those who did not (Table 2).

| HPA Lanolin used as solution | Other solution used | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue/symptom | % of those with issues | Issue start (av weeks) | Issue end (av weeks) | Issue duration (av weeks) | Breast-feeding duration (av weeks) | Issue start (av weeks) | Issue end (av weeks) | Issue duration (av weeks) | Breast-feeding duration (av weeks) |

| LRNP − all symptoms | 76.5 | 1.9 | 7 | 5.1 | 33.2 | 1.3 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 26.5 |

| LRNP − general nipple tenderness/soreness | 75.5 | 1.9 | 6.5 | 4.6 | 33.5 | 1.3 | 7.3 | 6 | 26.2 |

| LRNP − cracked nipples | 57.9 | 1.2 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 31.6 | 1.4 | 7.4 | 6 | 25.6 |

| LRNP − nipple flushing (redness) | 28.8 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 31.9 | 1.4 | 8.4 | 7 | 27.2 |

| LRNP − scabbing | 28.2 | 0.7 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 24.2 | 1.2 | 8.2 | 7 | 30.3 |

| LRNP − exuding (sticky or bleeding) nipple | 25.7 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 27.1 | 1.4 | 7.3 | 5.9 | 24.9 |

Discussion

Mothers face a variety of challenges when establishing a sustainable breastfeeding relationship with their infant, even if they enter motherhood with a determination to breastfeed. Issues during breastfeeding itself lead to physical damage of the epidermis of the nipple, effectively causing a superficial wound and leading to pain. Unlike other wounds, which can be protected and allowed to heal, the act of breastfeeding leads to a repeat insult of the damaged tissue thus exacerbating the issue, delaying healing and increasing pain. Some causes of nipple pain can be rectified through education on positioning and attachment, or remedy of an underlying physical or medical cause (Cadwell et al, 2004; Darmangeat, 2011; Kent, 2015). However, many mothers stop breastfeeding during these early days and weeks postpartum due to LRNP with no clear underlying cause.

The data presented here is consistent with that published previously (IFF, 2013; Bourdillon, 2020) with a high breastfeeding initiation rate, followed by a sharp reduction in breastfeeding prevalence in the weeks following birth. Differences in breastfeeding duration were observed in the group which exclusively breastfed (average 35 weeks) compared to those who combination fed from birth (average 15 weeks). This is interesting but unsurprising as it is likely that the mothers who used formula alongside breastfeeding from the outset were also those having the most issues. Introducing formula feeds can also lead to a reduction in supply, making sustained breastfeeding even more challenging (Walker, 2015). However, rather than seeing the introduction of formula from birth as contributing to breastfeeding being stopped earlier than intended, an alternative view is that without combination feeding to supplement breastmilk during the difficulties experienced in those early days, breastfeeding may have stopped even earlier or not started at all.

Of the 1084 women included in the study, 68% reported that they experienced some physical issues relating to breastfeeding itself. By far, LRNP was the most common; 76% of those with issues had experienced it (n=562) which was 52% of the total mothers surveyed. Engorgement, mastitis and blocked ducts were also cited as issues experienced by many respondents while thrush, milk blister, inverted nipple and breast abscess were less common. It is important to note that this study focused on physical issues related to the breast itself and did not consider the other factors which may have impacted the mother's ability to breastfeed, such as pain from the birth itself, psychosocial factors or socio-economic pressures and challenges. These are increasingly acknowledged as contributing factors to breastfeeding duration (Li et al, 2008; IFF Research, 2013; Odom et al, 2013; Bourdillon et al, 2020).

The impact of LRNP on breastfeeding outcome was pronounced with 19% of those surveyed reporting it led them to stop breastfeeding totally while a further 29% stopped for a short time and/or increased formula feeds. Of those that stopped completely, the majority did so in the first month. Of the respondents, 52% with LRNP reported ‘no impact’ on breastfeeding outcomes. In this context, the option was selected by mothers who continued to breastfeed despite their LRNP and without changing their method of infant feeding. In another published study on the impact of birth-related pain on breastfeeding, conducted using the same methodology and with the same respondent demographic, the survey included an alternative option: ‘there was no impact on breastfeeding but it negatively impacted my mental health’ (Bourdillon et al, 2020). Nearly twice as many respondents selected this option compared ‘no impact’. It is possible that the breastfeeding issues experienced by this cohort may have resulted in a similar psychological impact. However, this data was not captured by the study.

The respondents who had experienced LRNP sought assistance and information from multiple, varied sources including healthcare professionals, friends, family and the internet. When asked what tools and solutions they had used to manage their LRNP, HPA Lanolin was used most frequently (31%), followed by nipple shield (21%) and other nipple creams (including non-HPA Lanolin) (20%). Some respondents listed multiple solutions they had utilised however, data was not collected on whether they were used sequentially or in combination. When the data was analysed to investigate whether the choice of solution led to any difference in breastfeeding outcomes for those who experienced LRNP, use of HPA Lanolin had a substantial positive effect. Only 11% of respondents with LRNP who used HPA Lanolin as a solution stopped breastfeeding completely, compared to 19% who used other solutions. Additionally, more of the respondents who experienced LRNP but said it did not lead them to change their feeding method were using HPA Lanolin as a solution than anything else (59% HPA Lanolin versus 44% other solution).

When asked about the symptoms of LRNP, the symptoms experienced by respondents who used HPA Lanolin lasted a shorter time than for those who had not. Furthermore, those respondents who used HPA Lanolin as a solution for their LRNP breastfed for an extra 6.7 weeks on average compared to those that didn't (33.2 weeks compared to 26.5 weeks). This represents a substantial 25% increase in breastfeeding duration compared to those who didn't use HPA Lanolin and a 19% increase compared to the average duration of 28 weeks for all 1084 respondents.

This data is very interesting, given that the conflicting outcomes and conclusions of previous studies on lanolin for breastfeeding problems. Several studies have reported a similar clinical benefit when using HPA Lanolin; Abou-Dakn and colleagues (2011) compared treatment with HPA Lanolin to breastmilk and found that the HPA Lanolin group experienced faster healing, fewer complications, decreased pain and improved breastfeeding outcome at 14 days, compared to those that used expressed breastmilk. A second study by Neto et al (2018) reported that treatment of pain and nipple trauma with HPA Lanolin achieved better results than with breastmilk, this time over seven days. Several other studies have also reported lanolin as positively impacting the clinical outcomes for nipple wounds, demonstrating a benefit compared to comparative solution (Brent et al, 1998, Tanchav et al, 2004; Coca et al, 2008); all but one of the studies used HPA Lanolin. However, other studies have not reported a clinical benefit of HPA Lanolin over the comparator or control, instead noting improvement was similar for all treatment groups (Cadwell, 2004; Dennis, 2014; Jackson and Dennis, 2017).

One study by Mohammedzadeh et al (2006) had three treatment groups; one group was treated with lanolin, one with expressed breastmilk and one control group received no treatment (although all groups received help with technique correction). The author reported that the lanolin group was slower to show improvement in pain and slower to heal than the breastmilk or control groups. However, the participants were instructed to wash the nipple before feeding to remove the lanolin (the other groups were not instructed to wash). This unnecessary step meant the groups were no longer directly comparable and actually the act of repeated washing of the wounded nipple may have contributed to the delay in healing reported by this cohort.

The data presented here demonstrates the wide range of breast-related issues suffered by new mothers as they establish breastfeeding. This is key to understanding why there may be inconsistencies in the published data around HPA Lanolin and other nipple-care interventions. The mothers included in such studies will have a diverse range of underlying causes contributing to the issues they are experiencing-each unique to them alone. Therefore, the success of any one solution in healing a wounded nipple and helping reduce subsequent pain will depend on a variety of exogenous factors which cannot be readily controlled; if the root cause of the nipple damage is not identified and resolved, then the solution will be less effective. Education on technique goes some way to addressing this, however many confounding factors, especially those relating to physiological aspects of either the mother or infant, are difficult to identify and may be impossible to fully solve. Even something as simple as an increase in number of feeds per day, or a single feed where the infant positioning and attachment was sub-optimal, could impact the outcome of individual mothers and the subsequent conclusions of comparative studies, especially when the samples size is small.

The substantial sample size of this study makes it a valuable snapshot of the physical challenges experienced by mothers when establishing breastfeeding and how they felt this impacted their breastfeeding outcomes. When interpreting the findings, the retrospective nature of the study design should be considered; as the data collected was based on self-report and retrospective recall, it is possible that the mothers misreported their experiences, a consideration for any retrospective survey based study. It should be noted that mothers were not asked whether they had breastfed previously. While this is known to have an influence on breastfeeding experience, the omission of this question is not considered to impact the conclusions presented here. It is important to acknowledge that some of the LRNP reported by women in this study is likely to have had an underlying cause which, if resolved, could have improved the issue. Crucially however, the respondents themselves, looking retrospectively at their breastfeeding journey, identified the nipple pain they were experiencing as LRNP, distinct from the other medical causes of nipple pain which were presented as options.

Ongoing education, advice and support from healthcare professionals on correct infant positioning and attachment is essential to positively impact breastfeeding success. However, such support may not always be available or accessible at the precise time needed. HPA Lanolin is another solution which is commonly used in the early days and weeks of breastfeeding. While lanolin does not have any direct pain relieving properties in the same way that other solutions such as hot/cold therapy and hydrogels do, it effectively manages the cause of the pain, the wounded nipple, by providing an occlusive barrier, supporting natural moist wound healing and therefore decreasing the pain felt by a mother as her nipple heals.

For many women, the LRNP they experienced had no clear underlying cause which could be ‘fixed’-the prospect of breastfeeding with this pain indefinitely may be daunting or simply unmanageable. The lack of definitive reason for the pain they are experiencing may also lead to feelings of guilt or failure at a time when maternal mental health is fragile. Interestingly, some of the studies which reported no superiority of HPA Lanolin over the comparator treatment for healing or pain end points did find that the women who used HPA Lanolin were more satisfied with their breastfeeding experience and were more satisfied with their treatment (Dennis et al, 2014; Jackson and Dennis, 2017). For new mothers, solutions and advice are crucial in supporting them through their breastfeeding issues to allow them to breastfeed for as long as they intended. The data presented here indicates that HPA Lanolin is a key solution used by mothers in the management of LRNP, and one which they perceive as having a significant positive effect on the physical symptoms and pain associated with nipple trauma. Use of HPA Lanolin was also associated with a substantial increase in breastfeeding duration which ultimately aids women in meeting their personal breastfeeding goals and improves overall breastfeeding rates.