Shoulder dystocia is a relatively common phenomenon that most midwives will encounter as they care for women in labour. Evidence suggests that the incidence rate varies between 0.58 and 0.7% (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), 2012) and can result in significant neonatal mortality and morbidity. Therefore, all health professionals involved in caring for women during labour and birth should be prepared to manage this obstetric emergency. For the purposes of this article, the term midwife will be used to describe the primary care giver, although this role could apply to midwives, doctors or paramedics.

The RCOG adapted Resnick's (1980) definition and state that shoulder dystocia is defined as ‘vaginal cephalic delivery that requires additional obstetric manoeuvres to deliver the fetus after the head has delivered and gentle traction has failed’ (RCOG, 2012: 2). Despite this clear definition being accepted for many years, shoulder dystocia is under-reported. When discussing management of shoulder dystocia, students anecdotally report that midwives often refer to ‘difficult delivery of the shoulders’ that resolves with the use of the McRoberts position, and are often reluctant to make the diagnosis of shoulder dystocia. However, in order to provide safe and effective care in future pregnancies, and minimise potentially expensive compensation claims, it is essential that accurate diagnosis and documentation occurs. If care is based on the definition proposed by RCOG, then any additional manoeuvres that are used to facilitate delivery of the shoulders (including the use of McRoberts position) mean that a shoulder dystocia has occurred. Compensation claims to the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) between 1 April 2000 and the 3 March 2010 included 250 claims for shoulder dystocia with a combined value in payments of £103 520 832 (NHSLA, 2012). Therefore it is important for women, their babies and families and employing NHS Trusts that shoulder dystocia is effectively managed.

Shoulder dystocia is difficult to predict antenatally since 48% of cases occur in normal birth weight babies (less than 4kg) (Baskett and Allen, 1995). However, it is recognised that larger babies are at increased risk of dystocia; therefore, pre-labour risk factors such as maternal diabetes, raised body mass index (BMI), or fetal macrosomia should raise the midwife's awareness and be communicated to other members of the multidisciplinary team. Other pre-labour risk factors include a previous history of shoulder dystocia and induction of labour. The reccurrence rate where women have been affected by shoulder dystocia in previous pregnancy varies widely—between 1 and 25% (RCOG, 2012). Clinical factors that suggest delay in the progress of labour, such as augmentation, delay or arrest of labour, and instrumental birth are also risk factors for shoulder dystocia (RCOG, 2012). However, distinctive signs of shoulder dystocia may be apparent and can be recognised by a slow, creeping birth of the head, face and chin, the head remaining close to the vulva or retracting (turtleneck sign), and a lack of restitution and lack of descent of the shoulders (RCOG, 2012) causing increasing impaction if not managed effectively.

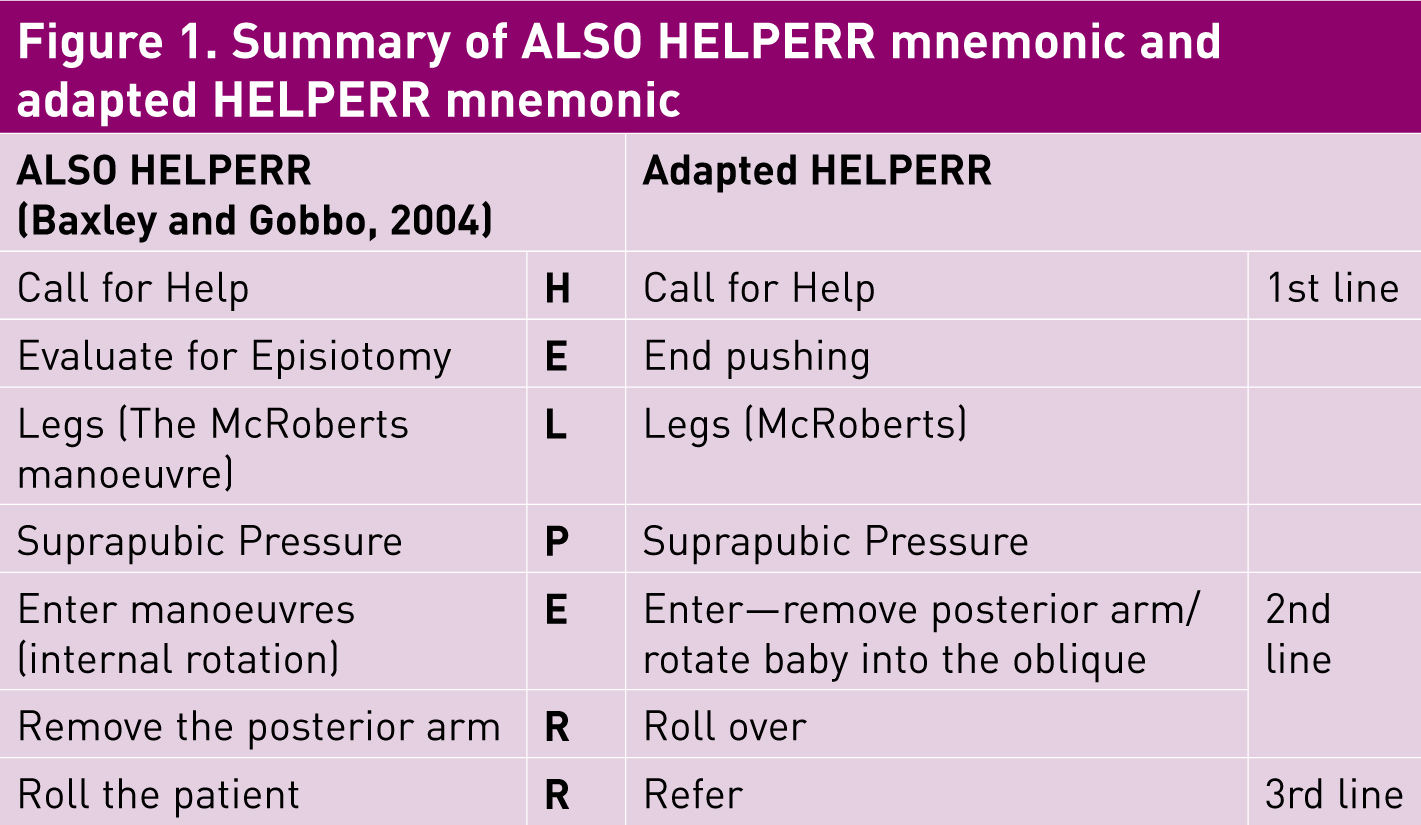

Effective management of shoulder dystocia relies on prompt recognition in order to minimise the delay in head-to-body birth interval and is aided by a clear understanding of the mechanism that is causing the dystocia. Staff training in the management of shoulder dystocia has been shown to reduce the incidence of adverse outcomes such as obstetric brachial plexus injury (Draycott et al, 2008; Grobman et al, 2011). In 2000, the Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) course manual introduced a systematic approach to managing shoulder dystocia using the mnemonic HELPERR (Figure 1) (Learner, 2004) that was widely adopted in clinical practice. It was discussed as an example of good practice by RCOG (2005) in their previous guideline for management. This mnemonic had a number of advantages; in particular it encouraged clinicians to move away from ineffective and potentially dangerous practices such as applying fundal pressure, and introduced an escalating set of manoeuvres designed to increase the space in the pelvis, and to attempt to rotate the baby into an oblique position to resolve the dystocia. The main advantage of the ALSO approach was the use of the mnemonic as an aide memoir for the provision of systematic care. Since that time, HELPERR has become synonymous with the management of shoulder dystocia in many NHS Trusts, but at the time of writing, the ALSO approach had not been altered for nearly 10 years.

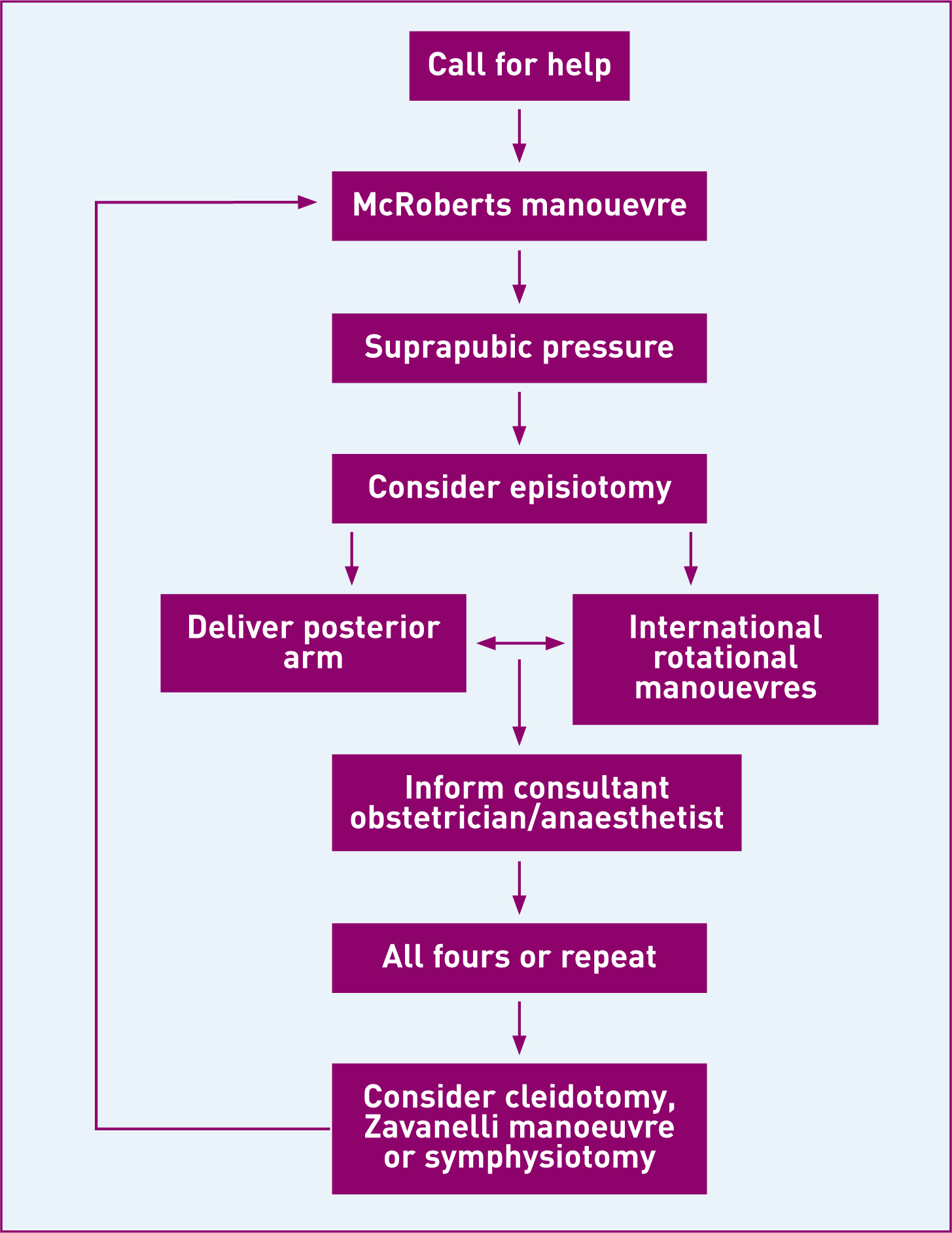

In 2012, RCOG introduced an updated version of their guidance for the management of shoulder dystocia (RCOG, 2012). RCOG aims to review all its green-top guidelines 3 years after publication, with the review process taking 18–24 until publication (RCOG, 2006). This means that their guidelines should be updated every 5 years. It is unclear why the shoulder dystocia guideline was not updated for 7 years. In the most recent guideline, RCOG moved away from the use of the ALSO mnemonic, which they had discussed in the previous guideline, and instead they developed an algorithm to guide care based on a review of the evidence (Figure 2).

As part of the evidence reviewed to update the guideline, some of the most common difficulties observed in shoulder dystocia training drills, such as the ALSO HELPERR mnemonic, were identified as; ‘not calling the neonatologist, failing to state the problem, inability to gain appropriate internal vaginal access, confusion over the internal manoeuvres, resorting to excessive traction to effect birth and use of fundal pressure’ (Winter et al, 2012:147). This was reflected in my own teaching. In particular, students often struggled to remember the sequence of internal manoeuvres using the ALSO mnemonic.

The module taught at Anglia Ruskin University requires student midwives to demonstrate safe management for women experiencing obstetric emergencies and is assessed by a randomly selected objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), which includes shoulder dystocia. The module has been positively evaluated by students for a number of years, and in particular they have enjoyed the use of a systematic approach to teaching, with the underpinning rationale for management, since they find it a useful aid to learning. In September 2012, guidance from the RCOG was incorporated into the module; however, students reported feeling confused by the algorithm, since it appeared more difficult to remember than the HELPERR mnemonic that they had seen in clinical practice. For the purposes of their OSCE, as in clinical practice, they have to demonstrate the management of a shoulder dystocia without the benefit of sight of the algorithm, so must have remembered a systematic approach to care. Benner's ‘Novice to Expert’ theory (1982) identifies that novice practitioners need clear guidelines to guide actions and cannot use discretionary judgment. Expert practitioners do not need these rules or guidelines in order to provide care but use knowledge, combined with experience and intuition to plan care. When teaching students, or when introducing a perceived change in approach to care for more experienced staff, it is useful to provide clear guidance that allows the student to integrate it with their existing knowledge. These basic ‘building blocks’ provide all students a foundation on which to apply further learning and clinical experience and so facilitate the transition from novice towards competence, proficiency and ultimately becoming expert practitioners.

In March 2013, the ALSO HELPERR mnemonic was modified to incorporate RCOG guidance in time for the next run of the module. This adapted model is not intended to replace the RCOG algorithm, but rather to aid learning. It is also useful to bridge the theory-practice gap. For over 10 years many Trusts have implemented the ALSO HELPERR mnemonic into practice, and this adaptation allows practitioners to build on existing knowledge rather than ‘abandoning’ it and replacing it with a new algorithm. This adapted algorithm has been trialled informally at teaching sessions at statutory training at a local NHS Trust and the midwives reported that they preferred this simplified approach to teaching the management of shoulder dystocia.

Management of shoulder dystocia

Clinicians have traditionally been taught to deliver the shoulders of the baby by applying gentle downwards, lateral traction to facilitate delivery of the anterior shoulder; however, this downwards movement has been associated with brachial plexus injury in both cases of shoulder dystocia and spontaneous vaginal delivery (Backe et al, 2008). Current guidance suggests that axial traction (along the long axis of the baby) should be used instead of the traditional downward traction (RCOG, 2012).

RCOG recommend the use of an algorithm detailing escalating manoeuvres to resolve shoulder dystocia. These are divided in to three levels and escalate in both the skill required by the practitioner and the invasiveness of the manoeuvre for the woman. First-line manoeuvres are initially attempted and only if they are unsuccessful in resolving the dystocia should the midwife move onto second- and finally third-line manoeuvres. The other change to the ALSO approach is that the midwife should attempt a manoeuvre and move on rather than persisting for 30 seconds.

First-line manoeuvres

First-line manoeuvres can be easily implemented by any clinician faced with a shoulder dystocia and are generally very effective. They need to be implemented immediately following recognition of a shoulder dystocia. Shoulder dystocia is associated with an increase in acidosis, hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) and an increase in neonatal mortality. However, the risks of HIE are minimal if the interval between the birth of the head and the body is less than 5 minutes (Leung et al, 2010). This timing should therefore be considered as optimal for birth.

Help

Calling for help remains a fundamental tenet of the management of any obstetric emergency, and in particular, senior staff should be called early in any potential or actual emergency situation. A recurring theme identified from the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the UK is the failure of early referral to senior staff, and the need to take such referrals seriously and promptly (Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE), 2011). In addition to senior midwives, senior obstetricians, and senior paediatric colleagues, where possible, someone should be delegated the role of a scribe. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) require that midwives keep contemporaneous records to meet the requirements of the Code (NMC, 2008). This is difficult in an emergency, but a scribe's record of events such as help called and manoeuvres undertaken can aid the completion of records after the event. Most importantly, cooperation must be sought from the mother to allow effective management. Effective, clear communication, both giving clear directions or instructions and using tone of voice that conveys the importance of cooperation, is essential in enabling this.

End pushing

Maternal pushing should cease in a shoulder dystocia (Gonik et al, 2003). It will not help to resolve the impaction of shoulders and if it was the contributing factor may cause further impaction. It may seem counter-intuitive to the woman to stop pushing in this case, but again, good communication with eye contact and clear verbal instructions will aid this. Stopping active pushing will allow the impaction to be resolved by the manoeuvres.

Legs

Up to 90% of cases of shoulder dystocia resolve with the use of the McRoberts position (RCOG, 2012). The woman should be laid flat on her back with one pillow under her neck for support. Her knees should then be moved upwards and placed alongside her chest towards her ears. The McRoberts position allows rotation of the pelvis and increases the anterior-posterior diameter by flattening the sacral promontory (Baxley and Gobbo, 2004). Since it is highly effective and minimally invasive, this first-line manoeuvre should be used before more invasive methods are used.

Pressure

Suprapubic pressure on the posterior aspect of the anterior shoulder reduces the bisacromial diameter (the diameter of the shoulders) and helps to turn the baby into the oblique. The midwife should direct an assistant to place their hands in a ‘CPR’ grip just above the symphysis pubis on the same side as the baby's back and push downwards at a 45 degree angle. When suprapubic pressure is combined with the McRoberts position efficacy is increased (Gherman et al, 1997); therefore the combination of the first-line manoeuvres should be effective in resolving the majority of cases of shoulder dystocia.

Second-line manoeuvres

Since they are part of an escalating algorithm of care, by their nature, second-line manoeuvres are more invasive than the first-line manoeuvres. The NMC essential skills clusters identify that at point of qualification midwives should be able to ‘identify and safely manage emergency procedures’ (NMC, 2009: 51), and that care should continue until appropriate help arrives. All midwives should be able to provide emergency care, therefore attendance at skills and drills training is usually part of mandatory training for midwives provided by NHS Trusts. Section 39 of the Code requires that ‘[midwives] must recognise and work within the limits of [their] competence’; therefore, if the midwife feels unprepared to undertake these effectively she should approach her Supervisor of Midwives to gain access to further training as a matter of priority (NMC, 2008).

The ALSO HELPERR mnemonic asks the practitioner to consider episiotomy as the second step; however, in reality, episiotomy is often not needed as many cases of shoulder dystocia will resolve with the McRoberts position. Episiotomy may be useful if the midwife is considering internal rotational manoeuvres, but this will require considerable skill on behalf of the attendant to perform safely when the baby's head has been externally birthed, since it is an obstruction for episiotomy. RCOG (2012) guidance advises that the second-line manoeuvres can be performed in either order dependent on the clinical situation as there were no randomised controlled trials comparing their effectiveness available for inclusion in their review. The midwife should use their clinical judgment taking factors such as condition and mobility of the woman, environment and midwife skill and training in to account (RCOG, 2012).

Enter

RCOG guidance advises that the whole hand is inserted into the sacral hollow where there is likely to be more room (RCOG, 2012). This moves away from ALSO advice to use the index and middle fingers to perform internal rotational manoeuvres (Hinshaw, 2003), and is advantageous as it increases power to undertake manoeuvres. After inserting the hand into the sacral hollow, the midwife needs to assess whether to either remove the posterior arm, or apply pressure to move the baby into the oblique diameter of the pelvis. This will depend on whether the midwife can easily access the posterior arm to birth it or whether the position of the baby makes this difficult.

When removing the posterior arm, the hand should be inserted along the front of the baby, feeling for the antecubital fossa and apply pressure that will cause the baby to flex the posterior arm. As it does so, the forearm of the baby can be grasped and swept across the baby's face to remove it from the vagina. This resolves the impaction and will facilitate delivery of the baby.

If it is not possible to remove the posterior arm, pressure can be applied to the posterior aspect of the posterior shoulder to move the baby into the oblique diameter of the pelvis which is wider than the antero-posterior diameter. This has the added advantage of reducing the bisacromial diameter to assist delivery. If necessary, the practitioner can change hands and continue the rotation through 180 degrees. There is no evidence to suggest that either of these manoeuvres is superior to the other, so will depend on clinical judgment (RCOG, 2012).

Roll over

If a woman is mobile, rolling her onto all fours may be desirable before internal manoeuvres are attempted, since the movement alone may reduce the impaction of the shoulder. In addition, movement in the sacroiliac joints can increase the diameter of the pelvis and thereby facilitate birth. This manoeuvre has been reported to have a significant success rate (Bruner et al, 1998), although it has not been subject to large scale trials. It is much less invasive for the woman than internal manoeuvres, and therefore may be preferred. It may also be easier for midwives or paramedics working in community settings where help may be more limited than in a hospital setting. Internal rotational manoeuvres may also be easier in an all-fours position since it gives the practitioner unimpeded access to the sacral hollow.

Refer

Most remaining cases of shoulder dystocia will have resolved with the use of second-line manoeuvres; however, in rare cases this is not achieved. In community settings where immediate referral is not possible, the practitioners should repeat the manoeuvres until transfer to an obstetric unit is possible; however, since the incidence of HIE increases with head-to-body birth interval the outcome is likely to be poor if this delay occurs.

Third-line manoeuvres

Third-line manoeuvres are not usually the province of the midwife, but will require referral to obstetric colleagues. The most common third-line manoeuvre in the UK is cleidotomy. In this, the fetal clavicle is fractured by applying pressure to it with the obstetrician's fingers, or by surgical division. It has the advantage of reducing the bisacromial diameter, and may have a protective effective effect against obstetric brachial plexus injury (Backe et al, 2008).

The Zavanelli manoeuvre, replacement of the fetal head with birth by caesarean section has been described by some American studies; however, the safety of this for the mother has not been studied. Any brachial plexus injury or significant hypoxia for the baby may have already taken place so it should be undertaken with caution (RCOG, 2012).

Symphysiotomy is the division of the cartilage in the symphysis pubis to facilitate birth and has been used in developing countries, but it is associated with poor neonatal outcomes and significant maternal morbidity, in particular urinary incontinence, when undertaken by inexperienced practitioners (Goodwin et al, 1997). It is not commonly undertaken in the UK, but colleagues working abroad may see this manoeuvre.

Responsibilities following shoulder dystocia

A prolonged shoulder dystocia has the potential to cause HIE; therefore, the baby should be handed to the paediatric registrar for immediate assessment following birth and resuscitation if necessary. It is good practice to take paired cord gases to assess the extent of fetal hypoxia (Armstrong and Stenson, 2007).

It is essential that accurate documentation is undertaken following any episode of care (NMC, 2008). It is vital following shoulder dystocia since compensation claims for obstetric brachial plexus injury (OBPI) are the third most common obstetric cause of litigation in the UK. The average claim for compensation in severe cases in the UK between 2000 and 2010 was £414 083 (NHSLA, 2012).

Long term consequences of shoulder dystocia

Women who experience shoulder dystocia have an 11% chance of developing a postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) due to the increased risk of atony, therefore active management of the third stage is recommended. There is also an increased risk of third or fourth degree tears (3.8%). Other consequences include vaginal and cervical lacerations, bladder and uterine rupture and spontaneous symphyseal separation (RCOG, 2012). Where internal manoeuvres have been performed, women are at risk of bruising and sepsis. Women who have experienced traumatic births also report post-traumatic stress disorder and postnatal depression, often as a result of the way they were ‘cared’ for, and how they were spoken to (Robinson, 2007). In emergency situations, forceful communication may have been required to gain the cooperation of the woman, so discussion of the rationale for this and the opportunity to discuss care may benefit the woman postnatally. If the baby requires care in the neonatal unit, maternal-infant attachment and lactation may also be affected. It is also important to consider the birthing partner who may also experience potential bereavement and psychological sequelae of traumatic birth events.

A long head-to-body birth interval is associated with an increased risk of HIE, and the associated fetal mortality (Leung et al, 2010). The baby may need resuscitation or transfer to the neonatal unit. Brachial plexus injury occurs in between 2.3 and 16% of deliveries complicated by shoulder dystocia (RCOG, 2012). Fractures to the clavicle and humerus may also occur.

Conclusions

Shoulder dystocia is a relatively common obstetric emergency, that can have very severe potential consequences. Fortunately, most cases of shoulder dystocia will resolve with minimally invasive techniques. A systematic approach to management will ensure that care is given in a logical order starting with the least invasive manoeuvres first. The latest RCOG guidance encourages this, and encourages the clinician to use their judgment and knowledge to assess which more invasive manoeuvres will be most effective. The use of this modified mnemonic should help all midwives to take a systematic approach to care.

| Diagnosis | Shoulder Dystocia | |

| Definition | ‘A delivery that requires additional obstetric manoeuvres to release the shoulders after gentle axial traction has failed”. Incidence 0.6–0.7% (RCOG, 2012) | |

| Recognition | Creeping head, no restitution, ‘turtleneck’ sign | |

| Risk factors | Previous history, Macrosomia, Diabetes Mellitus, Maternal BMI >30kg/m2, Induction, Prolonged 1st/2nd Stage, Secondary arrest, Instrumental vaginal delivery, Oxytocin augmentation | |

| 48% of shoulder dystocia occurs in the normal birth weight fetus and is unanticipated | ||

| Risk of Hypoxic Ischaemic Encephalopathy is minimal if delivery before 5 minutes | ||

| First-line manoeuvres | Help | Call for members of the multiprofessional team |

| End pushing | Ask the woman to stop pushing to avoid further impaction of the shoulder | |

| Legs (McRoberts) | Lie the woman flat, bring her to the end of the bed (or remove the end of the bed) and move her knees upwards towards her ears (90% cases resolve here) | |

| Pressure | Suprapubic pressure applied to the posterior aspect of the anterior shoulder | |

| Second-line manoeuvres (repeat as necessary) EITHER | Enter | Insert the whole hand into the sacral hollow

|

| Roll over | An all fours position may help delivery; it also may help when undertaking internal manoeuvres | |

| Third-line manoeuvres | Refer | Senior clinicians should be called

|

| When baby born | Cord Bloods from Baby, Hand to paed for resus, Documentation | |

| Long Term Outcomes | Mother | PPH (11%), Anal Sphincter damage (3.8%), Ruptured Uterus, Spontaneous Symphyseal separation, Soft tissue trauma, Bruising, Infection, PND, PTSD, Separation, Bonding, Lactation |

| Partner | Bereavement, PTSD | |

| Baby | Death, Hypoxic Ischaemic Encephalopathy, Brachial plexus injury, Admission to NICU—Separation/Bonding, fractured clavicle and humerus | |