A stillbirth is a baby delivered at or after 24 weeks of pregnancy showing no signs of life, irrespective of when the death occurred. The UK is noted to have one of the highest stillbirth rates in high-income countries (NHS England, 2016a). The stillbirth rate for the UK in 2017 has reduced to 3.74 per 1 000 total births from 4.20 in 2013 which represents 350 fewer stillbirths (Draper et al, 2019). However, stillbirth rates continue to be high for black women in the UK at 7.46 per 1 000 births in 2017 (Draper et al, 2019). This prevalence is also reflected in other European countries.

In a systematic review involving 13 separate studies in the UK, US, Denmark and Norway, which included 15 124 027 pregnancies and 17 830 stillbirths, it was found that black women were 1.5–2 times more likely to experience a stillbirth (Muglu et al, 2019). The stillbirth rate is an indicator of quality care in pregnancy (de Bernis et al, 2016). A fact that should move the prevention of stillbirth to the top of any national health promotion agenda. It is argued that the need to develop and implement a plan to improve maternal and neonatal health in any country should include a focus on reducing stillbirths (Goldenberg et al, 2011). Suggestions include increasing awareness of stillbirths in high-risk groups with the use of appropriate interventions targeted at high-risk communities (Flenadyl et al, 2016).

Reducing stillbirths is a priority for the NHS and is a mandate objective from the government to NHS England (2016a). In 2016, the secretary of state announced a national ambition to halve the rate of stillbirths by 2030, with a 20% reduction by 2020 (NHS England, 2016a). The NHS should recognise the importance of targeting black women in order to meet government objectives due to their increased risk of stillbirths. The Mothers and Babies Reducing Risk through Audit and Confidential Enquires (MBRRACE) perinatal mortality report demonstrated variation in stillbirth rates across the country, despite controlling for deprivation and other factors suggesting that all women were not receiving the best possible care (Knight et al, 2015). Due to variances in best practice, the ‘Saving babies' lives’ care bundle was developed (NHS England, 2016a). This bundle recommended the implementation of four strategies: reducing cigarette smoking in pregnancy, improving detection and management of fetal growth restriction, improving awareness and management of reduced fetal movement, and promoting effective fetal monitoring during labour (NHS, England, 2016a). All of these strategies focus on the general population with no specific recommendations for black women. The SPIRE study evaluated the impact of the interventions from the ‘Saving babies' lives’ care bundle, finding some impact on reducing the stillbirth rate (Widdows, 2018). However, the impact on stillbirths in black women from 2015–2017 only showed a small decrease from 8.17–7.46 per 1 000 births (Draper et al, 2019). Following this, a second version of the ‘Saving babies' lives’ care bundle was developed and the ambition to half the rate of stillbirths was brought forward to 2025 (NHS England, 2019). It was recognised that the second version of the ‘Saving babies' lives’ care bundle should not be implemented in isolation but as one of a series of important interventions to help reduce perinatal mortality and preterm birth (NHS England, 2019). This highlights a need to look at other variances that impact on black women receiving healthcare advice on stillbirth prevention and demonstrates the importance of reviewing their specific needs.

An inability to access antenatal care is known to lead to increased infant mortality in black and minority ethnic women (Department of Health [DOH], 2010a). Maternal death may also result in death of the fetus, highlighting the link between maternal and fetal wellbeing (United Nations Population Fund, 2010; Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries [CMACE], 2011; World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Investment in, and successful implementation of, high quality care and health promotion during pregnancy is one of the most effective ways to protect mother and baby, and promote healthy child development outcomes (Kerber et al, 2007). Clear and specific circumstances have been noted where differential access or uptake of services contributes to disparities; this includes antenatal diagnosis, timely diagnosis and treatment of pre-eclampsia, and labour induction for post-maturity (Flenady et al, 2016). Hence, a multitude of factors may contribute to stillbirths in black women with the underlying prevalence of lack of quality healthcare.

Preconception care and stillbirths

The preconception period provides an opportunity to intervene earlier to optimise the health of potential mothers and to prevent harmful exposures affecting the developing fetus (Lassi et al, 2014). National policy also recommends the promotion of preconception health to reduce perinatal mortality (DOH, 2007a). Similar to low-income countries, a package of care which involves community support groups and mass media/social networking could cater specifically to the needs of black women (Lassi et al, 2014). Women who receive preconception care are more likely to adopt healthy behaviours and therefore have better pregnancy outcomes. In addition, preconception care is particularly effective when men are involved and care is provided in the community (Dean et al, 2013). This strategy is particularly pertinent for black communities where cultural norms and qualities may have an influence on women's health-seeking behaviour (Esegbona-Adeigbe, 2018).

Despite the known benefits of preconception care, a cross-sectional survey in three maternity units in London showed that an awareness of preconception health among women and healthcare professionals was low, and responsibility for providing preconception care unclear (Stephenson et al, 2014). In this survey, 51% of all women who reported receiving advice from a healthcare professional before becoming pregnant were more likely to adopt healthier behaviours before pregnancy (Stephenson et al, 2014). This suggests that effective preconception care could be utilised to reduce the risk of stillbirths in black women. This fact was further supported by Hussein et al (2016) in a systematic review of eight randomised, controlled trials which showed improved knowledge, self-efficacy and health focus of control and risk behaviour in women who were offered preconception care; again, highlighting the importance of preconception care for optimum health during pregnancy for black women.

The issue with preconception health is implementation and where the responsibility should lie. In a qualitative study, some of the perceived barriers identified by general practitioners were time constraints, the lack of women presenting at the preconception stage, competing preventive priorities within the general practice setting, issues relating to the cost of and access to preconception care, and the lack of resources (Mazza et al, 2013). Other consistent themes identified in a systematic review of women's and healthcare professionals' attitudes towards preconception care service delivery highlighted ambiguity regarding which group of healthcare professionals should hold the responsibility for delivering preconception care to the population (Steel et al, 2016).

Another relevant point is the possible lack of presentation for preconception care, as maternal mortality and morbidity were higher in black women who presented late for antenatal care (Knight et al, 2016). Hence, it is important to refocus strategies on provision of preconception care as this period could be used to inform black women about the importance of antenatal care. Midwifery 2020 recognises the important role of the midwife in preconception care (DOH, 2010b). The midwife is well placed to offer preconception care to black women in a variety of settings, unfortunately often initial contact with a woman usually begins when she is already pregnant, resulting in a missed opportunity.

Antenatal care and stillbirths

It is already known that black women are poorer receivers of antenatal care resulting in poorer birth outcomes (Lewis, 2007; CMACE, 2011; Knight et al, 2016). Antenatal care is important in optimising maternal and fetal outcomes, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ([NICE], 2008), illuminating the impact of antenatal care on reducing stillbirths in black women. It is recommended that antenatal care should consist of a booking appointment at less than 10 weeks' gestation and no missed antenatal appointments (Knight et al, 2016). High quality antenatal care is expected to enhance a healthy pregnancy for mother and baby, addressing physical and socio-cultural normality during pregnancy, effective transition to a positive labour and birth, and positive motherhood (WHO, 2013). All of this points to the impact of antenatal care on stillbirths and the important role of the midwife in delivering care tailored to black women's needs.

The WHO's (2013) antenatal care model recommends providing pregnant women with respectful, individualised, person-centred care at every contact, a relevant issue for black women, and provision of relevant and timely information, and psycho-social and emotional support by practitioners. Through timely and appropriate evidence-based actions related to health promotion, disease prevention, screening, and treatment, antenatal care for black women reduces complications from pregnancy and childbirth, reduces stillbirths and perinatal deaths, and provides integrated care delivery throughout pregnancy (WHO, 2016). Early antenatal care is a critical opportunity for healthcare providers to deliver care and support, and to give information to black women in the first trimester of pregnancy. Health promotion in women by empowerment through gender equality and access to medical resources has been deemed relevant for preventing stillbirths (Ker, 2018). Continuity of carer models during pregnancy are also particularly important in improving outcomes for women and babies from black backgrounds and economically disadvantaged groups (NHS England, 2019).

Stigma and culture

Stillbirth is associated with stigma in many cultures, making it difficult to approach certain communities about reducing stillbirth rates. The response to the delivery of a stillbirth is dependent on the cultural belief and practices of the affected family (Homer and ten Hoope-Bender, 2016). There are many tribes among black British communities where stillbirth is one subject that is hardly discussed openly at home or within the community (Kiguli et al, 2016; Murphy and Cacciatore, 2017; Adebayo et al, 2019). Stillbirth has severe psycho-social adverse effects on the parents and on the family.

The psychological impact of stillbirth is strongly influenced by the social and cultural context where the woman finds herself (Acachie et al, 2016). Although information in this area is sparse, the influence of culture on stillbirth cannot be over-emphasised. Understanding the psycho-social impact, aggravating factors, coping styles and health system response to stillbirths are factors to be considered when trying to ameliorate the undue influence stillbirth has on the woman (Gopichandran et al, 2018). Perceptions about stillbirths exist, such as that the woman has failed as a mother, that evil spirits were involved in the death or that any baby who dies in utero was never meant to live (Goldenberg et al, 2011). This creates barriers to educating women and communities about prevention of stillbirth as it is seen as inevitable (de Bernis et al, 2016). So, a balance needs to be achieved by delivering the message on the importance of preconception and antenatal care, and understanding the cultural beliefs and stigma around pregnancy loss for black women.

Despite the recognition of the stigma and taboos associated with stillbirths, no efforts have been made to address this in national agendas or in the support given to mothers and families (Frøen et al, 2016). Nonetheless, the importance of educating high-risk communities on stillbirth prevention is crucial. This information needs to be readily available and tailored to black women's needs. In a scoping review, Garcia et al (2015) identified a lack of specific maternity interventions which were aimed to address culturally competent maternity services and the sharing of best practice addressing the increased risks of black women delivering in the UK. Cultural barriers to antenatal care for black women impedes the assimilation of such information. However, the greatest challenge is to overcome the stigma and taboo that keeps stillbirth hidden (Heazell, 2016).

Recommendations

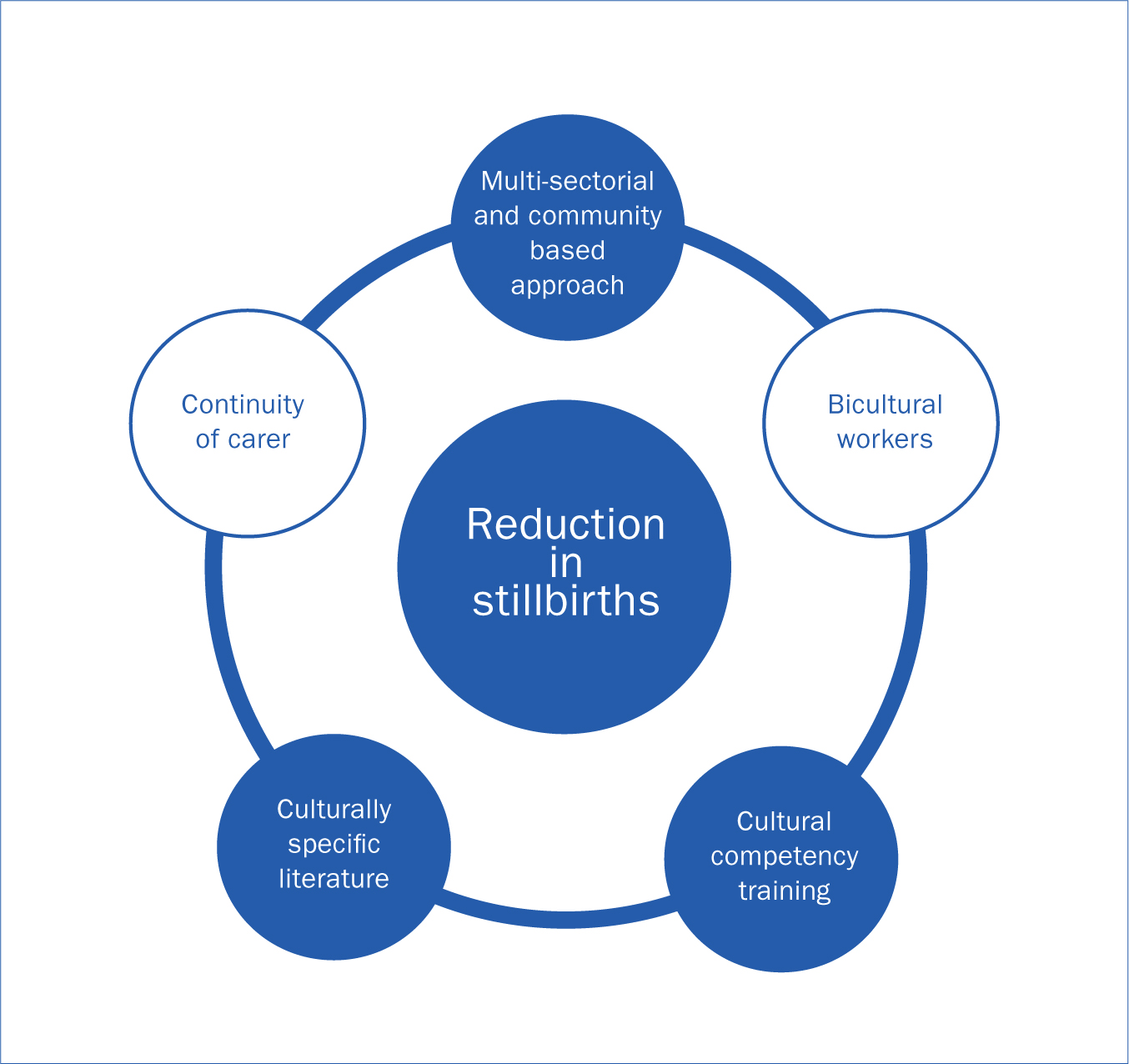

Research investigating inequalities and stillbirth in the UK is underdeveloped. This is despite repeated evidence of an association between stillbirth risk, poverty and ethnicity (Kingdon et al, 2019). However, targeting black women and providing information to black communities that highlights the prevalence of stillbirths is crucial. With ongoing improvements in antenatal and intrapartum care, and improved patient education, it is anticipated that the incidence of stillbirth in the UK can be substantially reduced (Woods and Heazell, 2018). Providing information to black communities where there is a stigma about the cause of stillbirth provides a challenge. To dispel the misconceptions in black communities that stillbirth is unavoidable requires a five pronged approach (see Figure 1).

A multi-sectorial and community based approach

A multi-sectorial approach involves collaboration among various stakeholder groups (eg government, civil society and private) and sectors (eg health, environment and economy) to jointly achieve a policy outcome (Salunke and Lal, 2017). It is believed that a multi-sectorial approach involving policymakers, politicians, religious leaders and local communities are essential to developing and implementing any successful programme for reducing health inequalities (Shingshetty et al, 2016; Salunke and Lal, 2017). The multi-sectorial approach has been used successfully in low- and middle-income countries (Lassi et al, 2012). However, the use of this approach is also beneficial to improving the uptake of antenatal care and health promotion in high-risk groups of women (Rasanathan et al, 2015; Shengelia, 2016; Rasanathan et al, 2017). The socio-cultural context of the woman should be considered when educating communities about the prevalence of stillbirth and preventive measures. Policymakers should also take cognisance of the influence of community and religious leaders in some black communities regarding health-seeking behaviour (Lassi et al, 2012; WHO, 2016). It is imperative that the focus begins in the preconception period for at-risk women as this is recognised as a crucial window for stillbirth prevention (DOH, 2007a; Stephenson et al, 2014; Hussein et al, 2016).

Use of bicultural workers

Riggs et al (2017) acknowledges the importance of bicultural workers and utilising group settings to deliver relevant health advice to women at increased risk of stillbirth. It is already acknowledged that preconceptions about the cause of stillbirths in black communities creates barriers to receiving preventable healthcare advice. Bicultural workers are able to provide information in ways that are asked for by women resulting in greater uptake and retention of health information, including information about when and how to seek help related to their pregnancy (Swanell, 2019). The use of personnel from the same cultural background of the woman will aid discussions around the stigma of stillbirth due to an awareness of their beliefs (Riggs et al, 2017; Yelland et al, 2019).

Bicultural workers are also beneficial in clarifying cultural concepts and the meaning of words and phrases (Lee et al, 2014). The avoidance of barriers created by not having a full understanding of particular beliefs around stillbirth is important as well as avoiding inadvertently causing offence. This would be minimised by the provision of health advice from someone who is from a similar background as the woman. The use of bicultural workers has been used in other healthcare settings and research projects, and has been very beneficial in engaging with communities (Boughtwood et al, 2013; Stapleton et al, 2015; McBride et al, 2017; Riggs et al, 2017).

Devising culturally specific literature on stillbirth prevention

Devising literature about the importance of preconception and antenatal care specific to migrant communities is an intervention that could empower women to manage their health before and during pregnancy (Yelland et al, 2019). The WHO (2015) recommends ongoing dialogue with communities as an essential component in defining the characteristics of culturally appropriate, quality maternity care services that address the needs of women and incorporate their cultural preferences.

Health promotion information should recognise ethnic diversities and take account of the cultural, political and economic contexts in which migrants/ethnic minority populations live (Chinouya and Madziva, 2017). Interventions to provide culturally appropriate services to the targeted populations may increase uptake of services (Jones et al, 2017). In addition, this will assist in improving acceptance of health advice regarding prevention of stillbirths in black communities.

Cultural competency training of key staff

The process of becoming culturally competent is key in ensuring quality healthcare services (Campinha-Bacote and Campinha-Bacote, 2009). National policies have supported the need to cater to black women and increase access to maternity care with a focus on cultural needs (DOH, 2004; 2007b; 2010a). The RCOG (2008) maternity care guidelines encourage cultural sensitivity to motivate vulnerable and hard-to-reach women to engage with maternity services. NICE (2010) guidance for women with complex social factors, which include migrant black women, were developed as women still did not understand the healthcare system and how it worked, and reported lack of cultural sensitivity from providers.

A National Maternity Review commissioned to improve choice and safer care for women demonstrated that women from different backgrounds felt that healthcare professionals needed to understand and respect their cultural and personal circumstances more (NHS England, 2016b). Therefore, a rationale is provided to accept the importance of black women's expectations of receiving culturally competent healthcare. Systematic reviews have shown that the behaviours of healthcare providers can contribute to health disparities (Young and Guo, 2016; Abrishami, 2018). Training and development of maternity services personnel is important in understanding cultural perceptions of stillbirth in black communities so that advice is tailored to dispel myths. This will work better when all maternity services staff are trained and supported to work with black women. Improving midwives' cultural competency would also better equip them to respond to the needs of black women (Aquino et al, 2015). In addition, the development of new roles such as prevention of stillbirth champions, advocates and link worker roles, and appropriately trained maternity support workers, integrated into both the hospital and community antenatal and postnatal care teams are also recommended (DOH, 2007b).

Continuity of carer models

Continuity of carer is one of the main themes in the ‘Better births’ model which aims to foster and facilitate relationships of mutual trust between women and midwives (Dunkley-Bent, 2016; Rayment-Jones et al, 2019). The importance of this model to black women is the opportunity to discuss fears and concerns which could be fostered by a trusting relationship (Origlia et al, 2017). This is particularly pertinent when midwives need to explain risk of stillbirth without this relationship as women may not wish to hear this information (Hollowell et al, 2012; Chilvers, 2015, Rayment-Jones et al, 2019). In a Cochrane systematic review of 15 trials, comparing midwife-led continuity models of care with other models, it was found that 17 561 women who had continuity of care experienced less fetal loss before and after 24 weeks plus neonatal deaths (Sandall et al, 2016).

Continuity of carer is also a proven model for reducing stillbirths evidenced by the Albany practice, where care was provided to 2 568 women over a 12.5-year period where more than half (57%) were from black, Asian and minority ethnic communities (Homer et al, 2017). Discussions regarding prevention requires sensitivity and an awareness of black women's needs and fears during pregnancy which may be divulged once trust and respect is present and can be achieved by the midwife through continuity of care.

Conclusion

It is clear that the prevalence of stillbirth in black women highlights an important issue that needs addressing. The increased stillbirth rate for black women highlighted in perinatal mortality reports signifies a variance in healthcare provision (Knight et al, 2016; Draper et al, 2019). Although some specific causes of stillbirth in black British communities are speculative, lack of appropriate preconception and antenatal education and care are amongst the main factors in stillbirths. While preconception and high-quality antenatal care are recognised strategies to reduce this disparity, other methods are required to begin to target the issues arising from stigma around stillbirths in black women.

Educating at-risk communities and placing reduction in stillbirth rates at the top of public health agendas requires interventions targeted at high-risk groups (Frøen et al, 2016). Therefore, the right steps must be taken to bring about the desired solution to this challenge. A more intensive community based approach that considers cultural stigmas and beliefs, involvement of culturally trained staff and continuity of carer will make great advances in reducing the risk of stillbirths in black women.