In the UK, at least one in five women experience some form of poor mental health during the perinatal period (Knight et al, 2023). In 2023, the MBRRACE report highlighted that poor mental health conditions remain a significant cause of death in the perinatal period, accounting for 10% of maternal deaths between 2019 and 2021 (Knight et al, 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic also had a significant influence on mental wellbeing, not only because of the virus itself but because of its impact on the NHS. Restrictions to NHS services, parenting support groups and social restrictions often left pregnant women without sufficient help and support during and after pregnancy, further exacerbated by lack of government support for healthcare facilities and carers (Trenholm and Dilks, 2023). These restrictions resulted in feelings of isolation in addition to parental ‘burnout’ and an increase in levels of maternal depression and anxiety, which may have been avoided had they received better support (Lane, 2021; Wall and Dempsey, 2023).

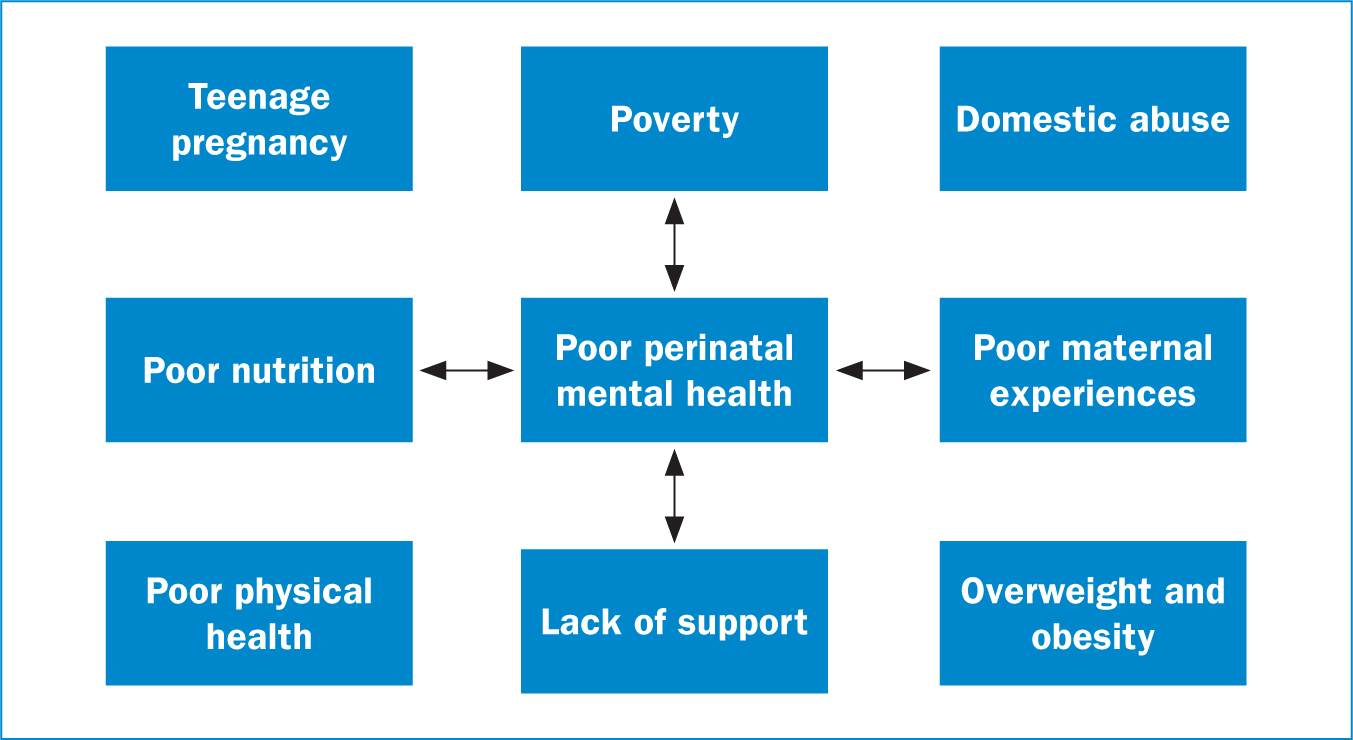

Poor perinatal mental health is associated with psychological and physical harm, such as preeclampsia, haemorrhage, premature birth and stillbirth, all of which may act as a catalyst for a worsening mental state (Howard and Khalifeh, 2020). It is crucial to note the multifactorial and complex nature and the overlap between potential risk factors and consequences (Figure 1).

Maternal mental healthcare

Despite some financial investment into mental health services, there is a growing rate of mental health conditions resulting from a lack of effective facilities, services and support for those with poor perinatal mental health (Trenholm and Dilks, 2023). Midwives, as the main care providers for pregnancy, are expected to recognise, assess and refer all women who are at risk or appear to have mental health problems during pregnancy (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2020). However, research shows that healthcare professionals, including midwives, lack the required knowledge, skills and confidence regarding perinatal mental health, and have expressed a need for further training to support women with mental health problems (Savory et al, 2022).

In the non-pregnant population, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that physical activity can have a positive impact on a person's mental wellbeing; however, this concept is often neglected in maternity guidelines (NICE, 2020; Smith and Merwin, 2021). Physical activity is defined as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure’ (World Health Organization (WHO), 2024) and although physical activity and exercise are distinct definitions, they are commonly used interchangeably. There are several potential explanations of how exercise can improve depressive symptoms and mental wellbeing.

Neuroplasticity

Using a broad description, neuroplasticity is the ability of the nervous system to adapt its structure in response to stimuli and is a critical element of adaptive learning, cognitive abilities and recovery (Smith and Merwin, 2021). During pregnancy, it is theorised that there is significant adaptation to the maternal brain and its plasticity, influencing behaviours such as caregiving, emotional regulation and social cognition (Barba-Müller et al, 2019). Although these neurological changes may be normal, women may be physiologically predisposed to impaired mental health during pregnancy, even in what would be considered a ‘low risk’ pregnancy. However, exercise elicits several mechanisms that can promote neuroplasticity, shown in Table 1, through (Smith and Merwin, 2021):

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Neurotrophic factors | This group of proteins aid neuron growth and differentiation and are essential for nervous system function and development |

| Hippocampus volume | This region of the brain plays a significant role in memory formation, learning and emotional regulation |

| Cortex volume | The outer layer of brain tissue plays a key role in thinking, learning, memory and emotional regulation |

| Neuroinflammation | The inflammatory response of the central nervous system and nervous tissue |

| Neuropathway connectivity | Connections and pathways between different regions of the brain aid brain function, behaviour and cognitive processes |

Adapted from Smith and Merwin (2021)

Through stimulating these neuroplastic mechanisms, it is possible that exercise influences the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety and can serve as a promising non-pharmacological intervention to reduce risk or reduce severity of symptoms.

Chronic inflammation

Inflammation is a series of cellular and molecular processes that aid bodily responses to tissue damage (Cerqueira et al, 2020), and is deemed a normal physiological response to development and growth in pregnancy. Although increased levels of pro-inflammatory markers are normal during a healthy pregnancy, they may disrupt neurological pathways and increase susceptibility to depression (Cerqueira et al, 2020; Smith and Merwin, 2021). In the non-pregnant population, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive proteins, are associated with depression, with a mendelian randomisation study suggesting that there may be a causal relationship (odds ratio: 1.35; 95% confidence interval: 1.12–1.62; P=0.0012) per unit increase (Kandola et al, 2019; Khandaker et al, 2020). However, exercise may act as a barrier to depression through its long-term effects on inflammation. It has been found that exercise can reduce inflammatory markers, such as tumour necrosis factor-α, C-reactive proteins and interleukin, while also reducing stress hormones, such as cortisol. Although there is an immediate stress response after exercise that causes proinflammatory signalling, this is only temporary and chronic exercise training leads to an overall reduction in basal inflammatory levels (Wang et al, 2023).

Psychosocial mechanisms

Psychosocial mechanisms may include improved self-efficacy through increasing self-confidence, inducing feelings of accomplishment and improving self-esteem through positive body image and improvements to physical quality of life (Smith and Merwin, 2021). In their meta-analytic review of body dissatisfaction during pregnancy and physical activity, Sun et al (2018) found that pregnant women who participated in physical activity had improved body image satisfaction. Furthermore, a qualitative study of pregnant women's experiences of physical activity showed that participants felt a reduction in anxiety through exercising, as they felt it was beneficial to their health and the health of their baby (Findley et al, 2020). It is possible that physical activity can alleviate poor psychological symptoms, without repercussions, and therefore should be encouraged safely.

Exercise and health

Exercising during pregnancy may not only improve perinatal mental health but also improve cardiovascular health and reduce the risk of pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus and excessive gestational weight (Dipietro et al, 2019; Witvrouwen et al, 2020). The UK Chief Medical Officers (2019) recommend a minimum of 150 minutes of physical activity per week during pregnancy, including resistance training. However, women are not meeting the recommendations during pregnancy; Meander et al (2021) reported that only 27.3% of >2000 women in Sweden met the recommendations. In turn, some may be living a more sedentary lifestyle while pregnant (Fazzi et al, 2017).

Perceived barriers to perinatal exercise may include a lack of education on the topic, lack of support, poor advice from family or healthcare professionals and pregnancy-specific reasons, such as fear of injury, pain, fatigue and lack of motivation (Connelly et al, 2015; Amiri-Farahani et al, 2021). Furthermore, there may be external barriers such as lack of funding or facilities access. In the non-pregnant population, it is well established that engaging in physical activity can reduce symptoms of depression or anxiety (Smith and Merwin, 2021) and the same could be true for pregnant women. Some barriers to physical activity can overlap with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, such as feeling unmotivated or fatigued (Badon et al, 2021). However, evidence shows that pregnancy can be a time for effective positive influence, as women may wish to optimise their health for the health of the baby (Badon et al, 2021). Mental health conditions could therefore be a motivator or barrier to exercise.

Effect on depression

There is currently no evidence that exercise programmes can be used to ‘treat’ depression; however some evidence suggests increasing physical activity levels while pregnant can reduce feelings or symptoms of depression or may be a protective factor against developing mild-moderate depression. Perales et al (2015) conducted a randomised control trial where pregnant women were assigned to either a supervised exercise programme three times per week for 30–32 weeks or to a non-exercise control group. Depressive symptoms were assessed via the Centre for Epidemiological Studies' depression scale pre- and post-intervention. Those in the exercise group had significantly lower depressive symptoms than those in the control group by the end of the intervention (P=0.005). More recently, in a similarly designed randomised controlled trial using the same scale, Vargas-Terrones et al (2019) found a significant decrease in levels of depression from baseline (12–16 weeks' gestation) to post-exercise intervention (30–40 weeks), when compared to the control group (P=0.041).

In contrast, Gustafsson et al (2016) conducted a randomised controlled trial where pregnant women participated in a 12-week exercise programme, attended one face-to-face session and were advised to exercise 2 more days per week. Their mental wellbeing was assessed using the psychological general wellbeing index, and no association was found between exercise and feelings of depression (P=0.90). However, only the in-person sessions were supervised and only 55% of intervention participants met the recommended 150 minutes of exercise per week, which may have contributed to conflicting results. Similar results were reported in the UPBEAT trial (Poston et al, 2015), which explored perinatal depression risk using the Edinburgh Depression Scale and found that increasing physical activity did not influence feelings of depression (P=0.26) (Wilson et al, 2020). Inconsistency between results may be the result of variation in study designs, such as participant characteristics or the duration or type of physical activity, emphasising the importance of care based on individual circumstances and experiences.

Effect on anxiety

Pregnancy-related anxiety can be caused and exacerbated by numerous factors, such as concerns about offspring health, childbirth, support and personal confidence (Ghezi et al, 2021). Although, theoretically, exercise interventions could have a positive effect on anxiety, evidence from randomised controlled trials is inconclusive (Davis et al, 2015; Gustafsson et al, 2016), while observational studies have shown conflicting results.

Davenport et al (2020) found that in a cohort of 900 pregnant women, those who engaged with and met the 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity guideline scored significantly lower in the state-trait anxiety inventory than those who did not (P<0.01), indicating that higher levels of physical activity reduced anxiety. Similarly, Kahyaoglu Sut and Kucukkaya (2021) used the hospital anxiety and depression scale to assess levels of anxiety in 403 pregnant women, and found that those who participated in regular physical activity had significantly lower anxiety scores than those who did not (P=0.01). Despite both scales being validated for pregnancy use, the generalisation of results is limited because of differences in the questionnaire constructs and measurements.

Conflicting results between randomised controlled trials and observational studies may also be the result differences the intensity of exercise and attrition to the programmes. Gustafsson et al (2016) did not report participants' overall activity levels; although women may have attended the face-to-face session, only 55% of participants participated in the recommended physical activity. Davis et al (2015) recruited participants who already had elevated levels of anxiety to participate in their study, where women participated in 75 minutes of yoga once per week. Again, no significant difference was found, but rather than confirming that exercise does not reduce anxiety, it may indicate that more intense or more frequent exercise is required for those who already experience higher levels of anxiety. Further research is required in this area, especially considering the anxiety measurement scale and type of exercise intervention.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Davenport et al (2018) evaluated 52 studies that assessed the influence of antenatal exercise on depression and anxiety. Overall, perinatal exercise was associated with a reduction of depressive symptoms when compared to no exercise (standardised mean difference: -0.23; 95% confidence interval: -0.36–0.09), but not with reduced anxiety symptoms (standardised mean difference: 0.06; 95% confidence interval -0.04–0.15). However, the review examined studies from 19 different countries, many of which may have significantly different standards of maternity care. As a result, it is difficult to compare populations, as their care (or lack of) may influence their mental health (Alderdice and Newham, 2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis by Cai et al (2022) found that higher levels of antenatal physical activity were associated with decreased odds of depression (standardised mean difference: -0.37; 95% confidence interval: -0.57–0.17) and anxiety (standardised mean difference: -0.45; 95% confidence interval: -0.64–-0.27). Although further research is required to understand the full impact, no evidence suggests that increasing physical activity is detrimental to mental wellbeing; encouraging all pregnant women (without contraindications) to increase their physical activity may not only improve their physical health but carries no adverse consequences to their mental health and may, in fact, improve it.

Implications for midwifery practice

A key driver in overcoming some of the potential barriers to physical activity during pregnancy is education (Nolan, 2017). As the main care providers during pregnancy, midwives have responsibility to provide a high standard of education, which ideally would include addressing concerns over exercise, how to exercise safely and reducing pain, fatigue and risk of injury. Unfortunately, despite the fact that successful education interventions have been shown to improve midwives' knowledge and confidence, midwives and healthcare professionals do not receive specific training on the topic (de Jersey et al, 2018; Newson et al, 2022). As a result, pregnant women are often deprived of the opportunity to receive this advice.

Newson et al (2022) investigated the opinions and experiences of pregnant women engaging in a healthy diet and the promotion of optimal gestational weight gain and physical activity. They found that women expressed disappointment because of the inconsistent guidance from healthcare professionals: ‘don't think [the] midwife has brought it up, anything about diet or physical activity to be fair’ (Newson et al, 2022). The lack of informative interactions with healthcare professionals meant that women were relying on other sources, such as the internet, to answer their questions: ‘all knowledge is Googled. Would be good for a midwife to discuss in some way’ (Newson et al, 2022). However, it is important to understand that midwives should not be blamed for a lack of information; instead, we must explore why information is scarce and inconsistent.

The Chief Medical Officers' (2019) and NICE (2025) guidelines are vague and do not provide specific support for healthcare professionals to advise on physical activity during pregnancy. Exercise may play a protective role against mental health problems during pregnancy and appropriate education and upskilling of healthcare professionals would give them the ability and confidence to educate and support pregnant women to participate in physical activity. This could improve maternal mental health by improving the quality of care provided. It could also potentially reduce the cost associated with maternal mental health problems, which is estimated to cost the NHS (2019) £1.2 billion per year, and in turn, improve the quality of services and education, aiding more preventative strategies rather than treatment.

For pregnant women who already have an existing or a suspected mental health condition during pregnancy, NICE (2020) outlines procedures such as referrals to the multidisciplinary team and consideration of pharmacology options. However, it does not mention any potential lifestyle adaptations, such as exercise. Healthcare professionals should be aware of what is offered in their local area, to be able to advise pregnant women on accessible and appropriate exercise facilities. For example, some hospital trusts support and offer free exercise classes during pregnancy in hospitals and local centres, which may be convenient for some women to attend (Mamafit, 2022).

As physical activity may play a protective role against worsening mental health, all healthcare professionals should educate pregnant women, aiming to overcome the potential barriers to improve maternal and offspring health. Midwives could improve the quality of care provided by:

These discussions should be incorporated into national guidelines such as NICE (2021), but also at local levels, as midwives need to be supported to provide quality care.

Conclusions

Physical activity is a safe, inexpensive and holistic way to improve both physical and mental health during pregnancy. Maternal mental health problems will continue to increase and have detrimental repercussions on women and families unless they are provided with safe, sufficient care and support. Pregnancy can be a particularly influential time in a woman's life; women can be motivated to seek help if required, both for their health and the health of their baby.

Increasing physical activity during pregnancy is known to improve women's physical health and there is some evidence that it can also improve levels of depression and anxiety. As poor maternal mental health has short- and long-term risks for the mother and her offspring, it is imperative that healthcare professionals provide optimal care and support. Emerging evidence shows that physical activity has the potential to play a preventative role in worsening mental health and a lack of acknowledgement of this may have detrimental outcomes. There is a potentially overlooked opportunity to improve maternal mental health by incorporating physical activity education in maternity care training. Furthermore, policymakers need to reflect this guidance in maternal care policies and guidelines. Overall, midwives should be proactive in supporting and encouraging women to be more physically active during pregnancy.