The specialty of obstetrics pioneered application of ultrasonography to clinical practice in the 1950s and subsequently was the driving force behind the major advances in medical ultrasound technology (Campbell, 2013). Utrasonography has transformed the care in pregnancy as well as how pregnancy is conceptualised and experienced by women (Gammeltoft, 2007). When asked to name three leading improvements in obstetrics and gynaecology in the 20th century, a former President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, replied, ‘Ultrasound, ultrasound and ultrasound’ (Campbell, 2013). This article discusses current and potential applications of ultrasound in the antenatal period, along with different models of integrating and delivering ultrasound services together with the increasing role of midwives in the context of recent advances.

Development of ultrasound in obstetrics

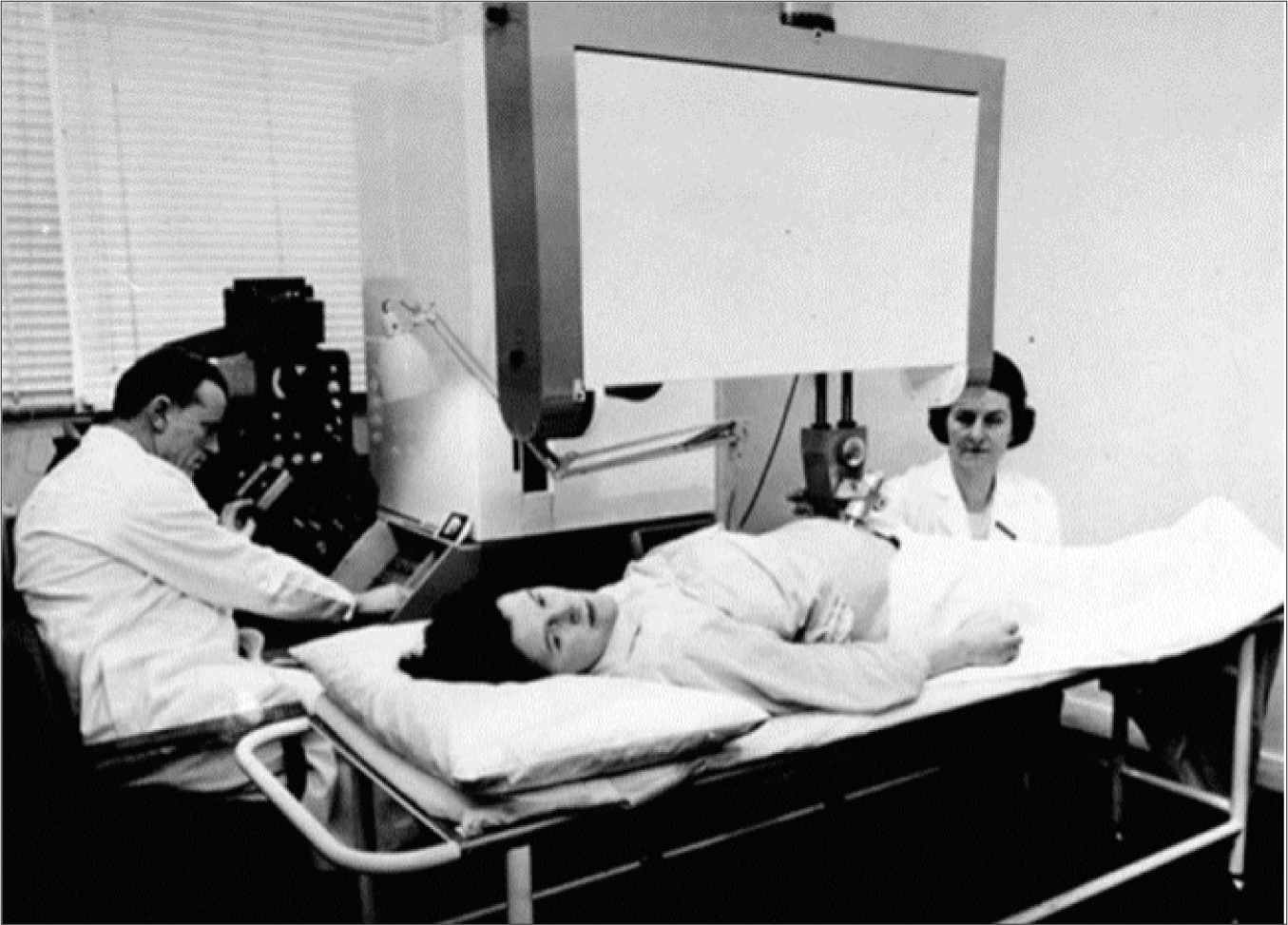

Obstetrician Ian Donald from Glasgow is credited to have designed and used the first practical ultrasound machine in clinical practice in 1958 (Campbell, 2013) (Figure 1). Since then, rapid progress has occurred in ultrasound technology from static to real-time scanners using grey scale high resolution imaging. Doppler technology was incorporated with colour, power and pulse wave imaging. Current high-specification ultrasound scan machines (HSUM) generally include colour/power Doppler, 3D imaging and advanced software for several medical/obstetric applications (Figure 2). Ultrasound delivers no ionising radiation and hence is safe to the smallest embryo with standard usage. Moreover, it is significantly less expensive than comparable imaging technologies like computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Furthermore, HSUMs are small enough to house in small clinic rooms. However, the operator has a greater degree of control, making ultrasonography more operator dependent than other forms of imaging. This clearly has implications for education, training, qualification and quality control. A minimum of a combined screening scan (11–14 weeks) and a fetal anomaly scan (18–20 weeks) are now part of routine antenatal care.

Figure 1. Professor Ian Donald using his early ultrasound scan machine (1958)

Figure 1. Professor Ian Donald using his early ultrasound scan machine (1958)  Figure 2. A specialist midwife using a modern ‘high specification ultrasound machine’

Figure 2. A specialist midwife using a modern ‘high specification ultrasound machine’

Point-of-care ultrasound

The most recent advance has been portable laptop-based machines and importantly pocket-sized ultrasound machines (PUM) making bedside use convenient. One of the definitions of ‘point-of-care ultrasound’ (POC-US) is a scan performed and interpreted directly by the treating clinician, brought to the location where the patient is receiving care (Dietrich, 2017). POC-US has been dubbed as the biggest advance in bedside diagnosis since the advent of the stethoscope 200 years ago (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2018). It has found important applications in cardiology, emergency medicine and family medicine, and soon may constitute a fifth pillar to bedside examination: inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation and ultrasound (Narula et al, 2018). POC-US achieves a specific procedural aim (eg to direct the needle to the correct location) or answers focused questions (eg is there a polyhydramnios or placenta praevia?). POC-US examinations can be used for emergency triage and may or may not replace comprehensive imaging procedures. Importantly, even comprehensive ultrasounds can be performed at bedside or patient location, either by a primary clinician or sonographers.

Early pregnancy scanning

Ultrasonography has revolutionised diagnosis and management of miscarriages, ectopic pregnancy and molar pregnancy. Transvaginal scanning is considered the modality of choice in diagnosing all early pregnancy conditions. Most ectopic pregnancies are now diagnosed early before rupture but significant expertise is required to avoid errors. Higher energy colour and pulse Doppler should be avoided in the first trimester to limit exposure to early embryo/fetus. In the UK for the last three decades, hospital-based ‘early pregnancy assessment clinics’ (EPACs) deliver integrated (one stop) ultrasound, biochemistry and specialist clinical assessment service. Different models of care are used in other countries, eg family physicians may deliver this service in the US, Ireland and other high-income countries.

First trimester combined screening scan (11–14 weeks)

Advent of ultrasound has allowed accurate dating of early pregnancies (paramount for subsequent antenatal care) superseding the old Naegele's rule based on uncertain last menstrual period and further variable ovulation/fertilisation timing. The early fetuses (crown-rump length) grow at an almost uniform rate of 1 mm/day until the second trimester, regardless of variables like maternal health, ethnicity, nutrition, smoking or parity (van Uitert et al, 2013). In addition, the detailed scan at 11–14 weeks allows for the detection of major malformations and markers of chromosomal abnormalities. The most specific marker for underlying chromosomal abnormalities is ‘nuchal thickness’ (NT). A ‘quadruple test’ combining NT with maternal HCG, pregnancy associated paraprotein alpha (PAPP-A) and maternal age allows estimation of the risk of common chromosomal abnormalities (trisomies 13, 18 and 21). Using a risk cut-off of >1:150 to conduct further testing (usually amniocentesis) will detect 82%–87% of the common chromosomal abnormalities (Malone, 2005). Specialist midwives perform the important counselling before and often after the first as well as second trimester ultrasound scans.

Mid-trimester fetal anomaly scan (18–20 weeks)

A second-trimester scan by a highly skilled operator is now standard to diagnose a wide variety of fetal growth and structural abnormalities. Women need to be counselled that the Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme in the UK currently looks for major abnormalities, namely markers of common trisomies, anencephaly, spina bifida, cleft lip, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, exomphalos, major heart defects, renal agenesis, lethal skeletal dysplasia. Some diagnoses may be missed and other less serious abnormalities may or may not be detected. The accessary 3D photographs and moving images (4D) facilitate bonding between parents and babies (Figure 3). Many women and their partners may seek additional scans solely for this purpose which can be performed by non-accredited sonographers but should not be seen as a substitute for structured, validated and audited fetal ultrasonography. When abnormalities or uncertainties are detected, it is very anxious time for the parents requiring support, advice and sometimes referral to fetal medicine centres.

Figure 3. A 3D ultrasound scan photo at 20 weeks

Figure 3. A 3D ultrasound scan photo at 20 weeks

Selective vs routine third trimester fetal growth/wellbeing scans

Antenatal stillbirth is devastating for the parents and about 30% of these babies are small for gestational age (SGA). In many other countries including the UK, women are not routinely scanned in late pregnancy but selectively on the basis of risk factors, complications or suboptimal symphyseal-fundal height. This approach will not identify all fetal growth restricted pregnancies (Sovio et al, 2015) but outcomes have improved since the introduction of customised growth charts and modified population growth charts (Intergrowth-21st, 2021; Perinatal Institute, 2021). Moreover, there is no strong evidence that untargeted universal growth scanning in the third trimester reduces adverse neonatal outcomes. This is reflected in the variable international practice.

In the Netherlands, midwifery practices have variable preference for routine third trimester ultrasound (Henrichs et al, 2019). In Germany, two routine ultrasound scans are offered in the third trimester. A Cochrane review in 2015 comprising 13 trials with 34 980 women showed no benefit of routine third trimester scan (Bricker et al, 2015). A Dutch randomised trial of 13 046 women in 2019 also showed no benefit of routine late scan in low-risk women (Henrichs et al, 2019). The value of detecting large for gestational age fetuses by routine ultrasound remains questionable (Bricker et al, 2015). Furthermore, for one additional correctly diagnosed SGA baby, there were two false positive SGA diagnoses (Sovio et al, 2015) and the increased medicalisation of pregnancy (risks of anxiety, operative intervention and iatrogenic prematurity) with routine imaging presents a difficult balance.

The situation is further complicated because up to 70% of non-anomalous antenatal stillbirths are not SGA and it has been proposed that there may be subacute uteroplacental insufficiency mainly affecting fetal oxygenation. This would result in fetal blood flow redistribution for a brain-sparing effect. Umbilical artery and fetal middle cerebral artery Doppler pulsatality indices (PI) have shown promise in this regard and are now being incorporated into fetal growth and wellbeing scans (Saving Babies' Lives, 2019). Once a diagnosis of SGA (more importantly growth restriction) has been made, regular ultrasonography with Dopplers has a major role in management of these cases.

Handheld Doppler ultrasound fetal heart rate monitors

These portable and widely available devices incorporate ultrasound and Doppler principles to produce audible fetal heart rate (FHR) tones and display the instantaneous FHR. Midwives use them with every antenatal contact with mothers for reassurance and for intermittent auscultation in low-risk labours in the UK. The more advanced ‘trace display Doppler monitors’ have not been well studied or popular. In resource-poor countries where cardiotocography is not available for even high-risk cases, the trace display Doppler devices may provide a compromise. Low-cost, wireless, self-guided fetal and maternal heartbeat monitors with a smartphone-based interface have been trialled in antenatal telehealth consultations, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Porter et al, 2021). Importantly, without medical supervision, the Royal College of Midwives (2017) and the Kicks Count charity strongly advise against home use of commercially promoted over-the-counter cheap FHR Doppler monitors as they can falsely reassure women when the fetus could be in distress.

Increasing role of midwives in sonography

Traditionally, most obstetric scans were performed by sonographers accredited after a two-year training programme. With a shortage of sonographers, there has been a move to upskill midwives to meet the increasing number of obstetric ultrasounds, particularly the third trimester growth scans. Midwives have an option of learning the full range of obstetric ultrasound skills or individual modules eg early pregnancy or third trimester fetal growth scans. Importantly, midwives provide a ‘one-stop service’, where they perform an ultrasound, explain the results and counsel women about further care and management options. Some scans can be performed in community clinics, delivering more care closer to home. In the UK, the care bundle to improve perinatal outcomes emphasises the continuity of midwifery led care with ultrasound scanning as an integral part (Saving Babies' Lives, 2019). In-house and virtual training programmes have also been developed to train midwives in more basic ultrasounds, such as presentation scans. The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology (2021) has an active outreach program training midwives in several developing countries.

Pocket-sized ultrasound scanners in resource-rich and poor settings

Today, the smallest size ultrasound scanners comprise of a handheld transducer wirelessly connected to a smartphone or a tablet. These PUMs are far less expensive (around £3 000) although lack pulse-Doppler function. A recent systematic review found strong correlation (reliability) when evaluating patients with ascites, hydronephrosis, plural effusions, aortic aneurysms and for use in obstetrics and gynaecology (Rykkje, 2019). In trained hands,, they have been shown to be reliable as a tool to triage patients in obstetrics in gynaecology (Sayasneh, 2012). In the third trimester, PUMs have been found to be reliable for placental site, fetal presentation, fetal number and amniotic fluid volume (Galjaard, 2014). The Pregnancy Outcome Study in the UK showed that 54% of breech presentations at 36 weeks were not suspected on clinical examination (Wastlund, 2019). Undiagnosed breech presentation in labour can increase the risk of perinatal morbidity/mortality and precludes unhurried informed choice by women and option of external cephalic version. The importance is not simply captured by cost-effectiveness although Westland et al (2019) showed that a routine 36-week scan for fetal presentation would be cost-effective below £19.80 per woman.

In resource-poor settings, PUMs have potential to revolutionise maternity care bringing down the cost of ultrasonography and making POC-US a reality in remote areas by trained birth attendants or primary physicians. In rural Tanzania, introduction of the simplified ultrasound scanning improved number of antenatal visits and motivated facility delivery (Mbuyita, 2015). However, obstetric referrals increased from 148 to 765. A solution may be that the ultrasound scan images by midwives using battery operated PUMs can be transmitted to a specialist using mobile-phone technology and simple modems without loss of image quality (Dietrich, 2017). Focused research is required to clearly demonstrate reductions in mortality/morbidity from synergy between telehealth and compact ultrasound technology (Swanson, 2019).

Summary

Ultrasound scanning has revolutionised the antenatal care by giving an unprecedented insight into fetal anatomy, growth and wellbeing. It has also enabled some intrauterine fetal therapy (Campbell, 2013). Many challenges persist, particularly in detecting fetal compromise in third trimester. Midwives are taking an increasing role in delivering obstetric ultrasound services. The march of medical ultrasound technology goes on and is expected to provide ongoing impetus to research and improvements in antenatal care.

Key points

- Medical ultrasound is safe even for the early human embryo. It is convenient and economical compared to other imaging technologies like CT or MRI

- A minimum of a combined screening scan (11−14 weeks) and a fetal anomaly scan (18−20 weeks) are now part of routine antenatal care

- A fetal growth and wellbeing scan in third trimester is generally performed based on clinical indications and risk factors

- Advances in medical ultrasound technology like colour/pulse wave Doppler imaging and pocket-sized ultrasound machines are revolutionising antenatal care in resource poor and rich countries

CPD reflective questions

- How would you counsel a woman having a first trimester combined screening scan?

- What fetal abnormalities can be detected by a mid-trimester fetal anomaly scan?

- What are the indications for a third trimester ultrasound scan?

- How would you counsel a woman having a third trimester fetal growth and wellbeing scan?