The contemporary definition of a midwife is greatly influenced by international organisations. In 1972, the International Confederation of Midwives' (ICM) definition of a midwife was formally accepted by other international organisations, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO). The definition was universal and reflected that a midwife is required to acquire specific education to be adequately prepared to become, and legally practise as a midwife (ICM, 2014a). However, the reality is that midwifery preparation differs from one country to another. The content of midwifery training often reflects the midwives' roles and tasks in the countries where they practise, the needs of women they serve (Marland and Rafferty, 2004) and the social perception and definition of childbirth in that country (Davis-Floyd and Jenkins, 2005), rather than a universal international definition. Therefore, although there are some similarities in the development of midwifery education from one country to another, the unique needs of women for childbirth as well as the social and political climates in different countries mean differences in the provision of midwifery education are necessary.

This article reviews the available documents on the development of midwifery education in Brunei. A literature search indicated that no research relating to this topic has been conducted, to date. The objectives of the literature review were to identify available information about the development of midwifery education in Brunei, identify the rationale for that development and determine the factors influencing midwifery education and the preparation of midwives in Brunei. Most of the available literature largely comprise official documents; for example, the State of Brunei Annual Report as written by the British Residents in Brunei and the Department of State Secretariat, Prime Minister's Office, Brunei (DSSPMOB); professional literature; and theses. A total of 23 local documents were located and reviewed, along with 21 international papers.

The need for midwifery education in Brunei

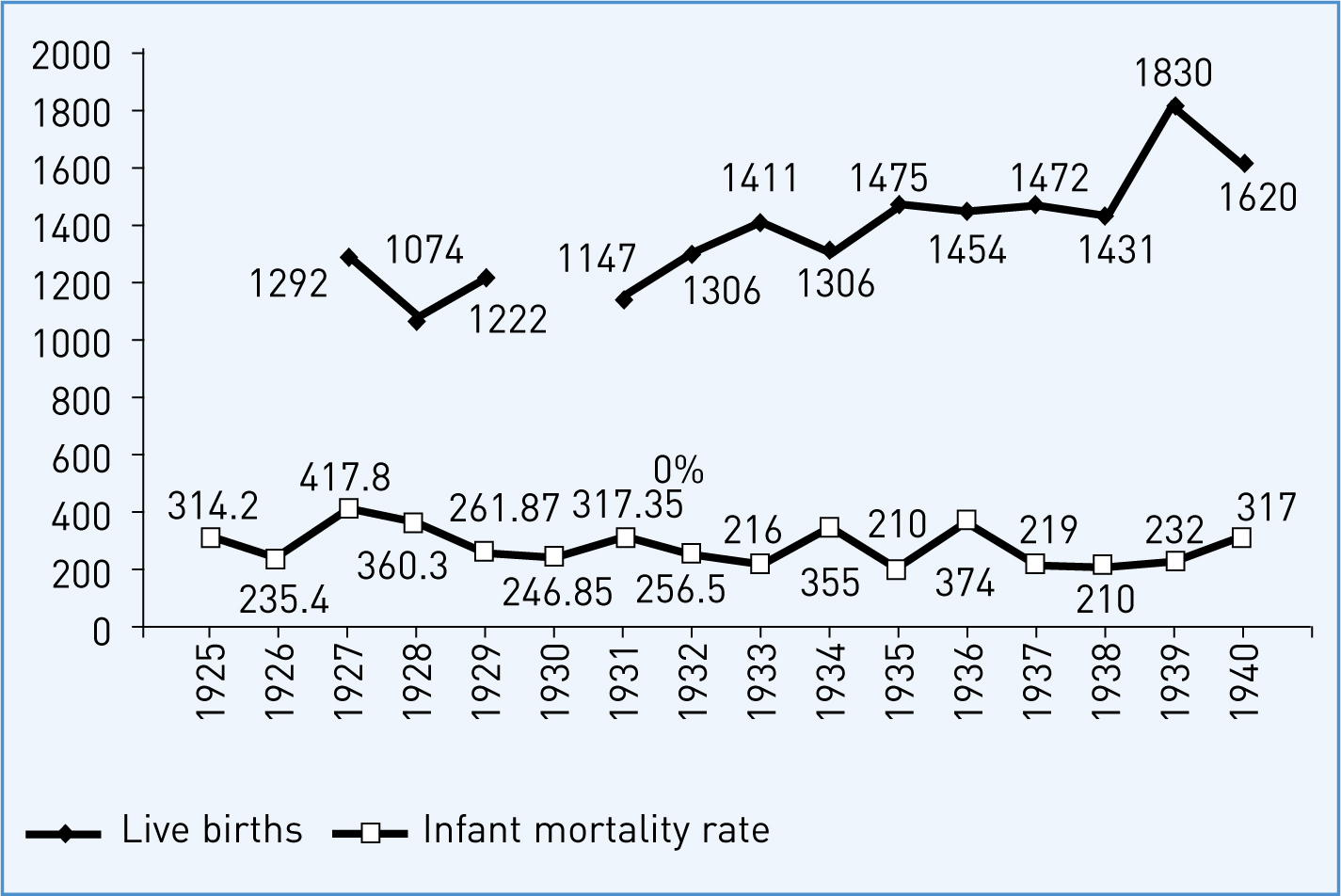

Similar to the early practice of midwifery as documented in other countries (Plummer, 2000; Biggs, 2004; Ortiz, 2005; Shillington, 2005), Brunei had no requirements for midwifery educational preparation until the early 1930s (McKerron, 1931). However, the practice of midwifery had been documented as early as the 1900s; when midwifery was reported to be conducted by the local bidan (translation: midwives) (Carey, 1934). The general term used to refer to a local midwife in Brunei is ‘traditional midwife’ (Lim, 1974). In other parts of the world, the term ‘traditional midwives’ is synonymous to traditional birth attendants (TBA) (ICM, 2014a). Until the 1930s, childbirth took place in the women's homes and there was no documentation of childbirth occurring in hospital. However, in the 1930s, it was reported that traditional midwives' practises resulted in complications for women and their infants during childbirth (McKerron, 1930; 1931; Carey, 1932; Abdullah, 2007). Traditional midwives were seen as untrained and unskilled; and their practices were viewed as unsafe and needed to stop (Carey, 1934). Traditional midwives in Brunei were thought to be incompetent in dealing with abnormal pregnancies, high-risk births and emergency situations (Black, 1938; 1939). Their knowledge and skills were viewed as inadequate, and critics stated they lacked the proper instruments and technology (Carey, 1934; Pengilley, 1939; Pretty, 1949a). The high maternal and infant mortality rate in Brunei is thought to be attributed to these inadequacies (Table 1; Figure 1) (McKerron, 1930; 1931; Carey, 1932; 1934; Pretty, 1949a; 1949b; 1950; Abdullah, 2007). The 1930s marked the beginning of the requirement for legal regulation of midwifery, and necessitated the establishment of formal midwifery education.

| Year | Number of births | IMR |

|---|---|---|

| 1925 | *not recorded | 314.2 |

| 1926 | *not recorded | 235.4 |

| 1927 | 1292 | 417.8 |

| 1928 | 1074 | 360.3 |

| 1929 | 1222 | 261.87 |

| 1930 | *not recorded | 246.85 |

| 1931 | 1147 | 317.35 |

| 1932 | 1306 | 256.5 |

| 1933 | 1411 | 216 |

| 1934 | 1306 | 355 |

| 1935 | 1475 | 210 |

| 1936 | 1454 | 374 |

| 1937 | 1472 | 219 |

| 1938 | 1431 | 210 |

| 1939 | 1830 | 232 |

| 1940 | 1620 | 317 |

IMR—infant mortality rate measured per 1000 live births

Early midwifery education

In response to the need for midwifery education, a maternity and child welfare clinic was set up in 1933, as a branch of the medical and health services in Brunei (Carey, 1934). A Singaporean-Chinese woman was hired to work as a maternity and child health nurse in the clinic by the Brunei medical and health services. No documentation was available on the name of this nurse and the prior qualifications she held that enabled her to be a midwife. A small number of women who had completed a minimum of 6 years of primary education were trained through apprenticeship with this nurse and under her supervision (Carey, 1934). During that time, the Brunei general educational system was similar to that of the UK. Year six was the highest education level in Brunei, and it was normal for many children to start school at an older age (around 10 or even 12 years old). The best achievers at the end of the 6-year primary education were sent to either Singapore or Malaysia for further study, while the remainder embarked on apprenticeship training, including training to become teachers, mechanics, carpenters, nurses and midwives.

This apprenticeship training in nursing and midwifery led to registration as nurse-midwives, as the training included components of both nursing and midwifery. At the end of the training period, the nurse-midwives were approved to practise midwifery by the Government of Brunei. However, there was no record of the exact length or coverage of this training.

Being an expatriate, the Government of Brunei initially feared that the Singaporean-Chinese nurse would not be acceptable in the Brunei community. Despite this, her services were in demand by the local Bruneian women and their families. By the mid-1930s, 90% of homebirths in Brunei were attended by the Singaporean Chinese nurse or nurse-midwives, rather than by traditional midwives (Carey, 1934). In 1933, the Government of Brunei planned to put forward a legal requirement that childbirth must be attended by a registered nurse-midwife, and a fine would be levied on any unregistered childbirth attendants attending a woman giving birth (Carey, 1934).

As a result of this, some traditional midwives begin to voluntarily seek midwifery education (Carey, 1934; Black, 1938; 1939). Because these midwives were identified as being unable to read or write, a basic midwifery training was designed for them by the Brunei Medical and Health Services (Black, 1939). This training included basic midwifery concepts for normal births and minor complications, and was delivered under the close supervision of an officer (either a nurse-midwife or a doctor) appointed by the Brunei Department of Medical and Health Services (Black, 1938; Pengilley, 1939). At the end of the supervision period, the competency of these traditional midwives was assessed and approved by the supervising officer. There was no lecture-style or classroom teaching; all training was conducted in the maternity ward of the maternity and child welfare clinic, with emphasis on practical aspects of maternity care, and without a properly designed curriculum (Black, 1939). No records of the length of time these traditional midwives spent in training were available. On approval of their competencies, the trained traditional midwives were then registered as midwives and legally approved to attend childbirth and care for infants at home and in the hospital.

There were three types of midwives in Brunei during the 1930s:

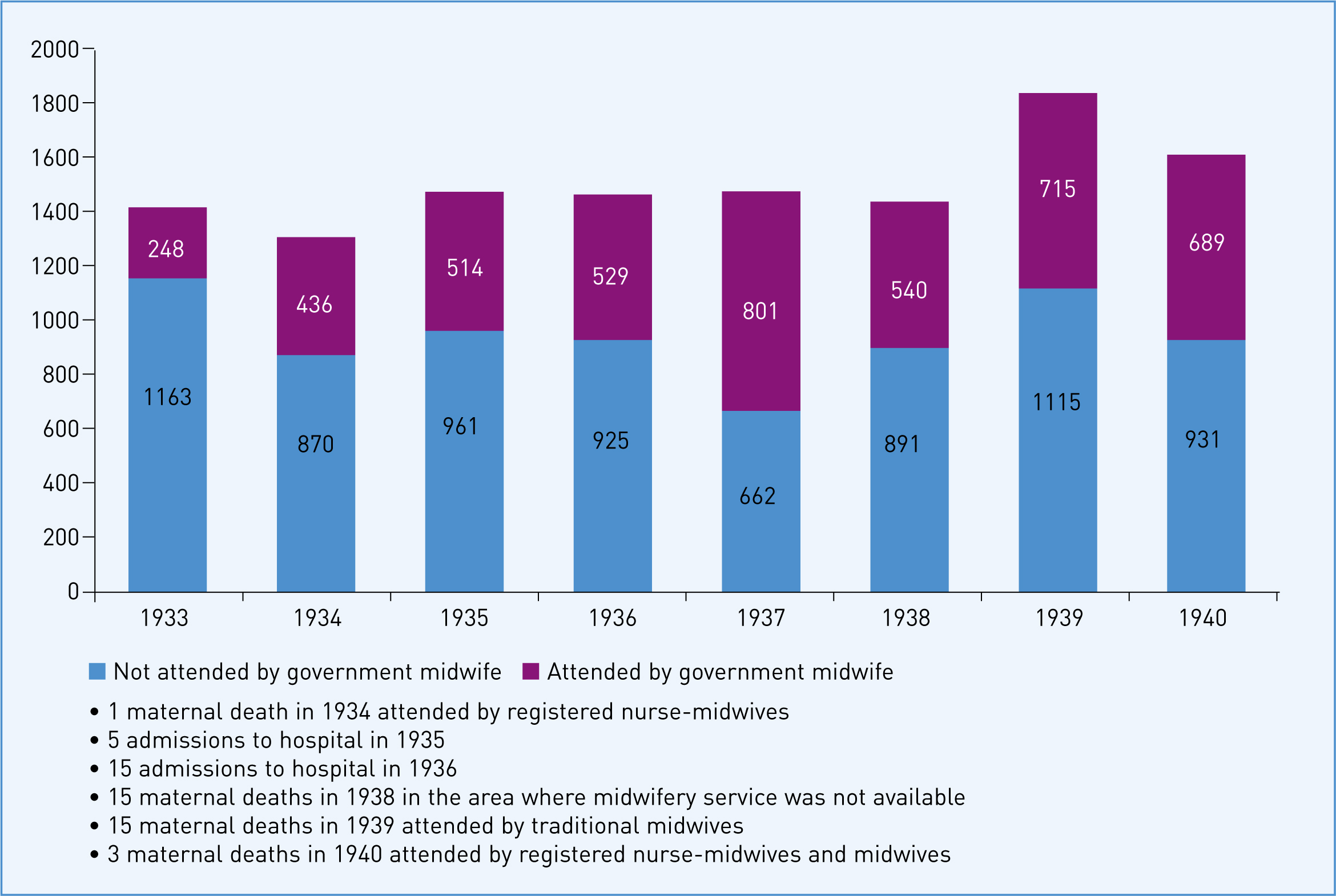

The number of homebirths attended by registered nurse-midwives and midwives as opposed to births attended by traditional midwives steadily increased once the legal regulation of midwifery came into force (Black, 1938; 1939; Pengilley, 1939; Abdullah, 2007). The literature also reported that during this time, maternal deaths often occurred where childbirth was still attended by traditional midwives and in remote areas of Brunei where midwifery services were unavailable (Black, 1939; Pengilley, 1939). Figure 2 presents the numbers of attended and unattended home births.

Establishment of midwifery education

Development of midwifery education was disrupted by World War II, particularly during the time of the Japanese occupation (1941 to 1945) of Brunei (Peel, 1946). The hospital was severely damaged and the child welfare and maternity building was completely destroyed. Post-World War II, the development of midwifery education was not a continuance of the previous development; midwifery was in a state of redevelopment, reconstruction and rehabilitation. At this stage, midwifery education focused on training more local midwives who resided in the rural areas that were not easily accessible due to poor road conditions (damaged by the war), distance and other geographical factors such as flooding (Peel, 1946).

A School of Nursing was established in 1946 in the capital city of Brunei, and formal nursing training was initiated in the same year using a pre-designed syllabus, including a midwifery syllabus, adapted from the General Nursing Council of England (Pretty, 1949a; Barcroft, 1952). In 1951, a midwifery unit was built adjacent to the School of Nursing and formal midwifery education commenced in the same year (Barcroft, 1952). This unit was later called the School of Midwifery (Abdullah, 2007). Administered under the Ministry of Health, the School of Nursing and the School of Midwifery were the only nursing and midwifery schools in Brunei at that time. Midwifery education was established for school leavers, and specifically for women who had no prior nursing qualifications but had completed at least 9 years of education (6 years of primary education and 3 years of secondary education) (Pretty, 1949a). In Brunei, students underwent 5 years of secondary education, which concluded at Year 11 with the acquisition of the General Certificate of Education qualification at the Ordinary level (GCE ‘O’ Level), endorsed by Cambridge University, UK.

The WHO, through the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), provided two public health sisters to teach in the newly established School of Nursing and School of Midwifery for an 18-month period, training local and supervising staff, and expanding their work in nursing, health visiting and maternity and child welfare (Pretty, 1949b). There is no record of the names of these public health sisters. A European public health nurse was also engaged on a 1-year contract to help train more nursing and midwifery staff (Pretty, 1950). However, there is no record of which European country this public health nurse came from.

On 1 January 1956, the first Midwives Act was launched by the Government of Brunei (revised in 1984, and incorporated in the laws of Brunei on Midwives, Chapter 139). The Midwives Act was described as an Act that regulates and controls the practice of midwifery, the registration of midwives and all matters related to midwifery. This document was a powerful tool governing the practice of midwifery in Brunei. Midwifery education became a legal prerequisite for those wishing to practise as a midwife; either through an institution approved by the Government of Brunei, by passing a midwifery examination conducted by the institution or through assessment of competency to practise as a midwife by an officer appointed by the Ministry of Health in Brunei. Penalties ranging from BND$400–16 000 were to be imposed for illegal practice as a midwife in Brunei (Clause 5, 9, 11, 12 and 14).

Reported in 1957, the training for traditional midwives to become registered midwives was also conducted at the School of Midwifery concurrently with the training of those school leavers mentioned earlier. The traditional midwives were trained by two WHO British health sisters (DSSPMOB, 1957). It was not clear in the report whether these sisters were those previously provided by the UNICEF or newly sent by the WHO. Traditional midwives' practices were assessed by these sisters; those whose practices were seen to be safe were approved, given midwifery kits and became registered midwives; and those who needed additional preparation to obtain approval were required to attend further training with the sisters (DSSPMOB, 1958). The WHO training of TBAs also commenced in Asia in the 1950s (Lefèber, 1994). Once the course was completed, a UNICEF midwifery kit was given to attendees (Mangay-Angara, 1974). While no documentation was available to confirm the nature of the training programme for traditional midwives in Brunei, it was likely that the assessment and training of these midwives was part of the WHO and UNICEF initiatives. In the rural areas of Brunei, access to qualified midwifery staff was still insufficient, and it was almost impossible to visit these areas due to the poor road conditions (Barcroft, 1952). This suggests that childbirth in these areas were likely to be attended by untrained traditional midwives, if attended at all. Table 2 presents the infant mortality rate for the years 1946 to 1955.

| Year | Live births | IMR |

|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 683 | 110 |

| 1947 | 1854 | 133 |

| 1948 | 1647 | 139 |

| 1949 | 2073 | 128.3 |

| 1950 | 2316 | 136.9 |

| 1951 | 2805 | 80.92 |

| 1952 | 2809 | 103.9 |

| 1953 | 2903 | 113.3 |

| 1954 | 3332 | 99.6 |

| 1955 | 3600 | 102.5 |

IMR—infant mortality rate measured per 1000 live births

In 1963, the midwifery programme became ‘direct entry’ (Certificate of Midwifery Division II)—a 2-year course offered to women without a nursing background (Abdullah, 2007). This midwifery programme was for women completing at least 11 years of education, and lead to registration as a midwife (6 years of primary education and 5 years of secondary education; becoming a trainee midwife also required passes in any two subjects at GCE ‘O’ level qualification). However, some cases of complicated childbirth could not be managed at home by registered midwives and required the presence of an obstetrician (Pengiran Anak Puteri Rashidah Sa'adatul Bolkiah College of Nursing, Brunei (PAPRSBCONB), 2008a). This resulted to the shift from home to hospital births in the late 1960s, which initiated a revision of the midwifery training structure (PAPRSBCONB, 2008b). Subsequently, a 1-year midwifery course for trained nurses was also introduced in the late 1960s (Certificate of Midwifery Division I) (PAPRSBCONB, 2008b). This training aimed to produce more competent midwives able to meet the challenges presented by the progress made in the obstetric and medical fields and meet expectations and requirements for providing a high standard of care to mothers and babies in hospital. This programme also prepared midwives to be more skilled in carrying out midwifery practice independently with less attendance by obstetricians (PAPRSBCONB, 2005).

By the early 1970s, there were two types of midwifery education; direct entry midwifery for school leavers (Year 11) leading to registration as a midwife; and a 1-year midwifery programme for trained nurses leading to the registration at a higher level of nurse-midwives. The midwifery curriculum was revised to meet the requirements of the former UK Central Council (UKCC) for Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors (now known as the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC)), in terms of the standard of content and the competencies of the midwifery programme. Being under the administration of the Ministry of Health, trainees in these two courses were considered to be part of the workforce while they underwent training (Abdullah, 2007).

Midwifery education in higher institutions

A College of Nursing named after the eldest Princess of His Majesty the Sultan of Brunei, the Pengiran Anak Puteri Rashidah Sa'adatul Bolkiah College of Nursing in the town of Gadong (the second largest town in Brunei) was established in 1986 to provide a higher level of nursing education (PAPRSBCONB, 2003). In 2003, midwifery education was initiated at the diploma level at the College, via two routes: those completing 5 years of secondary education, and for trained nurses. This was facilitated by the merging of the School of Nursing and School of Midwifery with the College of Nursing in 1999. This merger was intended to further enhance the educational programmes for nurses and midwives in Brunei (PAPRSBCONB, 2005). The merger also laid the foundation for the development of contemporary midwifery education. The former midwifery curriculum was revised and developed to be more consistent with the requirements of the UK's NMC (PAPRSBCONB, 2005). This included revision of the length of the courses: 3 years for the direct entry midwifery; and 18 months for the trained nurses. The student midwives were given ‘student’ status rather than trainee status, described as ‘supernumerary’ and were no longer considered part of the workforce during training. The 3-year direct entry midwife qualification was at a higher level than the previous 2-year direct entry programme.

Currently, the sole provider of midwifery education in Brunei is the PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences in the Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Responding to the command from His Majesty the Sultan of Brunei, the College of Nursing ceased to function in May 2009 and the staff was integrated into the Institute of Health Sciences (formerly known as the Institute of Medicine). The merger was necessary to move nursing and midwifery education forward to a higher status, at the degree level and above (Abu Bakar, 2008). In keeping with university-level education, midwifery education moved towards a degree level qualification, although the midwifery diploma course was still continued. Degree courses leading to the award of Bachelor of Health Sciences (Midwifery) were offered via three routes: post-GCE at the Advanced level (GCE ‘A’ Level as endorsed by Cambridge University, UK); for graduates of the 3-year Diploma in Health Sciences (Nursing or Midwifery); and, for qualified nurses or midwives with at least 3 or more years of work experience. The Diploma in Midwifery previously offered to trained nurses was upgraded to the Advanced Diploma in Midwifery qualification. Research degrees leading to Masters of Health Sciences and Doctors of Philosophy were also offered.

Midwifery education in Brunei and international standards

The State of Brunei Annual Reports demonstrates that development of the midwifery curriculum has been influenced primarily by the UK, as well as by various international organizations. One reason for these outside influences was that the state of health of Brunei's people in the 1900s, including maternal and child health, fell below minimal world standards; therefore, various international organizations became involved in the provision of midwifery education in Brunei. Another possible reason for the initial influence of the UK midwifery curriculum on midwifery education in Brunei may be the fact that Brunei was a British protectorate country for nearly 100 years (1888–1983). During the British protectorate, with the exception of religious matters, British Residents were influential in all administrative matters in Brunei. This would reasonably have carried over to the influence of the British midwifery education on Brunei. These influences are evident in Brunei's current midwifery curriculum, which was developed in line with the requirements of the UK's NMC. For example, the length of the midwifery programme should be no less than 18 months; the components of the practise to theory ratio should be no less than 50% practise, and no less than 40% theory (NMC, 2009); and achievement of a minimum standard for clinical competencies, such as conducting 40 births, 100 postnatal examinations, and 100 antenatal examinations.

It is envisaged that Brunei's midwifery education is recognised internationally, and comparable with other Western countries', specifically the UK (PAPRSBCONB, 2003). As a WHO member country, Brunei takes into account the international standards and requirements of the midwifery education outlined by the WHO (WHO, 1948; 1989; 1992; 1996; 2001). Brunei's midwifery education also adheres to the requirements of the international professional bodies and organisations, such as the ICM (PAPRSBCONB, 2003). Therefore, the development of the midwifery curriculum in Brunei has been indirectly affected by the standards and requirements of these international professional bodies and organisations.

Furthermore, there are various documents that contain rules, guidelines, policies and standards produced by international organisations. These documents include, for example, the Safe Motherhood Initiatives from the WHO (WHO, 1991), core documents from the ICM such as the ICM Global Standards, Competencies, and Tools, and the Philosophy and Model of Midwifery Care (ICM, 2014b; ICM, 2014c), and the Munich Declaration: Nurses and Midwives: A Force for Health (WHO, 2000). The contents of these documents legitimately set international and minimum standards required for midwifery education and practise worldwide. As a result, many countries, including Brunei, make reference to these international documents and strive to develop midwifery education that will produce competent midwives at an internationally recognised level. Similar to global trends, midwifery education in Brunei has been designed to achieve improvements in the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of midwifery services, as echoed in The State of the World's Midwifery (United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), ICM and WHO, 2014).

The structured midwifery education in Brunei has led to a gradual decrease in the maternal mortality and infant mortality rate. In 2013, the Department of Statistics estimated the Brunei population at around 406 200; and there were 6680 childbirths. In the same year, 450 legally practising registered midwives were recorded; and the infant mortality rate has drastically decreased to 7.6 per 1,000 live births (Department of Statistics, 2013). It was also documented that skilled attendance at birth was 99.9% where there were only two maternal deaths in 2013 (United Nations Children's Fund, 2014).

Limitations

Data gathered for this article are mainly from non-research sources. There are several limitations that should be taken into account. First, although the State of Brunei Annual Reports are first-hand accounts, there is a risk of recall bias, as the reports were written after the event. The contents of the annual reports were also found to be repetitive. Due to their official nature, they may also convey events constructed from the perspectives of the authority. The reports, being largely colonial, also pose possibilities that they might primarily present the views from a different social context to Brunei, and therefore should be seen from this perspective.

In addition, some documents such as those produced by DSSPMOB and PAPRSBCONB could have been produced by, and in the interest of, that particular organisation/institution for the purpose of documenting the development of the organisation/institution. Data from Abdullah (2007) are not research-based but critical and reflexive accounts of professional and personal experiences, thus, may not provide concrete empirical evidences. Despite these limitations, the present review laid a foundation for the development of midwifery education in Brunei, which could serve as a basis for analysing further development in the future.

Conclusion

Evidence showed that, as in other parts of the world, midwifery in Brunei was initially practised by untrained traditional midwives. The development of midwifery education in Brunei evolved from basic preparation to deal with normal low-risk births, to being able to assist obstetricians in managing high-risk pregnancies and care of infants. However, there is a need for further research to explore the many aspects of midwifery education in Brunei. For example, there is a need to determine whether modern-day midwives are being adequately prepared both in terms of theoretical and practical knowledge. Midwifery education worldwide is continually evolving to better address the needs of women and their children, and midwifery education in Brunei continues to move forward to be a part of this important initiative.