Autism is a neurodevelopmental disability affecting interpersonal communication and interaction, with a prevalence of more than 1% of the population (National Autistic Society, 2023). Outdated terms, such as ‘Asperger's Syndrome’ and ‘high’ or ‘low’ functioning, are no longer considered useful (Bargiela, 2019), with the current medical diagnosis being ‘autism spectrum disorder’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2019). A preferred term is ‘autism spectrum conditions’, which is compatible with the term ‘neurodiversity’, recognising that autism can be a disability in some environments but advantageous in others (Lai and Baron-Cohen, 2015). Henceforth, ‘autism spectrum disorder/condition’ will be referred to as ‘autism’.

In England, autism was the first disability to have its own Act of Parliament, The Autism Act 2009, which arose as a result of poor awareness of autism (Department of Health, 2010) and the multiple social disadvantages and health inequalities faced by autistic adults (Department for Education and Department of Health and Social Care, 2021). Autistic women have low rates of professional diagnosis, with 20% of autistic females diagnosed by the age of 18 years old (McCrossin, 2022).

The causes of existing inequalities in autism diagnosis for adult women appear to be twofold. First, autism has historically been understood to be a male condition (Wing, 1976), with both diagnostic criteria (Grace, 2021) and research having been based on autistic presentation in males (British Psychological Society, 2018). Second, autism has been considered a paediatric condition resulting in many autistic adults being undiagnosed as a result of the limited information about autism during their childhood (O'Nions et al, 2023). Both factors have put adult women, including those of childbearing age, at particular risk of underdiagnosis of autism (Lai and Baron-Cohen, 2015; Milner et al, 2019; O'Nions et al, 2023), although it should be noted that some individuals may prefer not to have a professional diagnosis. The highest proportion of females professionally diagnosed with autism in England is among those aged 15–19 years, with approximately 1 in 75 professionally diagnosed. This declines to approximately 1 in 130 females aged 20–29 years, 1 in 550 females aged 30–39 years and 1 in 850 females aged 40–49 years (O'Nions et al, 2023). Given that autism has a prevalence of 1% across all ages (Lai and Baron-Cohen, 2015), there are many undiagnosed adult females, many of whom are of childbearing age and may require midwifery care.

Autism is associated with various health implications, with reproductive-age autistic women having higher rates of diabetes, asthma, psychiatric conditions and experience of assault (Tint et al, 2020), as well as increased risks of antenatal and postnatal depression (Pohl et al, 2020; Hampton et al, 2022a; 2024), stress and anxiety (Hampton et al, 2022a). Alongside growing reports on health implications, there is an increasing body of literature from autistic women sharing their maternity experiences. While this work has come from personal interest and impact over many years, the diagnosis of autism in women is typically seen as a current topic, which is misleading. Grace (2020) discussed how she ‘masked’ her autism during pregnancy and comments that she ‘did not realise the barriers myself until I bumped into them’.

How individuals process information and deal with the potential sensory overload is unique to them; one person with autism is one person with autism (National Autistic Society, 2023). This means that each individual has a unique contribution to how they navigate the world in which they inhabit and what support they may require to do this (Kitson-Reynolds et al, 2015). Given the increasing evidence, and accounts of pregnancy and childbirth by autistic women, this literature review's aim was to identify what midwives in England can learn from studies exploring the experiences of autistic women in the antenatal, intrapartum, and early postnatal periods.

Methods

The PICO mnemonic (Stern et al, 2014) was used to identify key words and develop the research question: what can midwives in England learn from studies exploring the experiences of autistic women in the antenatal, intrapartum and early postnatal periods? A search strategy using the key words and synonyms, with Boolean operators and syntax, was applied to seven electronic databases, which were systematically searched:

- CINAHL via EBSCOhost

- Medline via EBSCOhost

- PsycINFO via EBSCOhost

- AMED via EBSCOhost

- Web of Science via Clarivate

- Scopus via Elsevier

- Cochrane Library via Wiley.

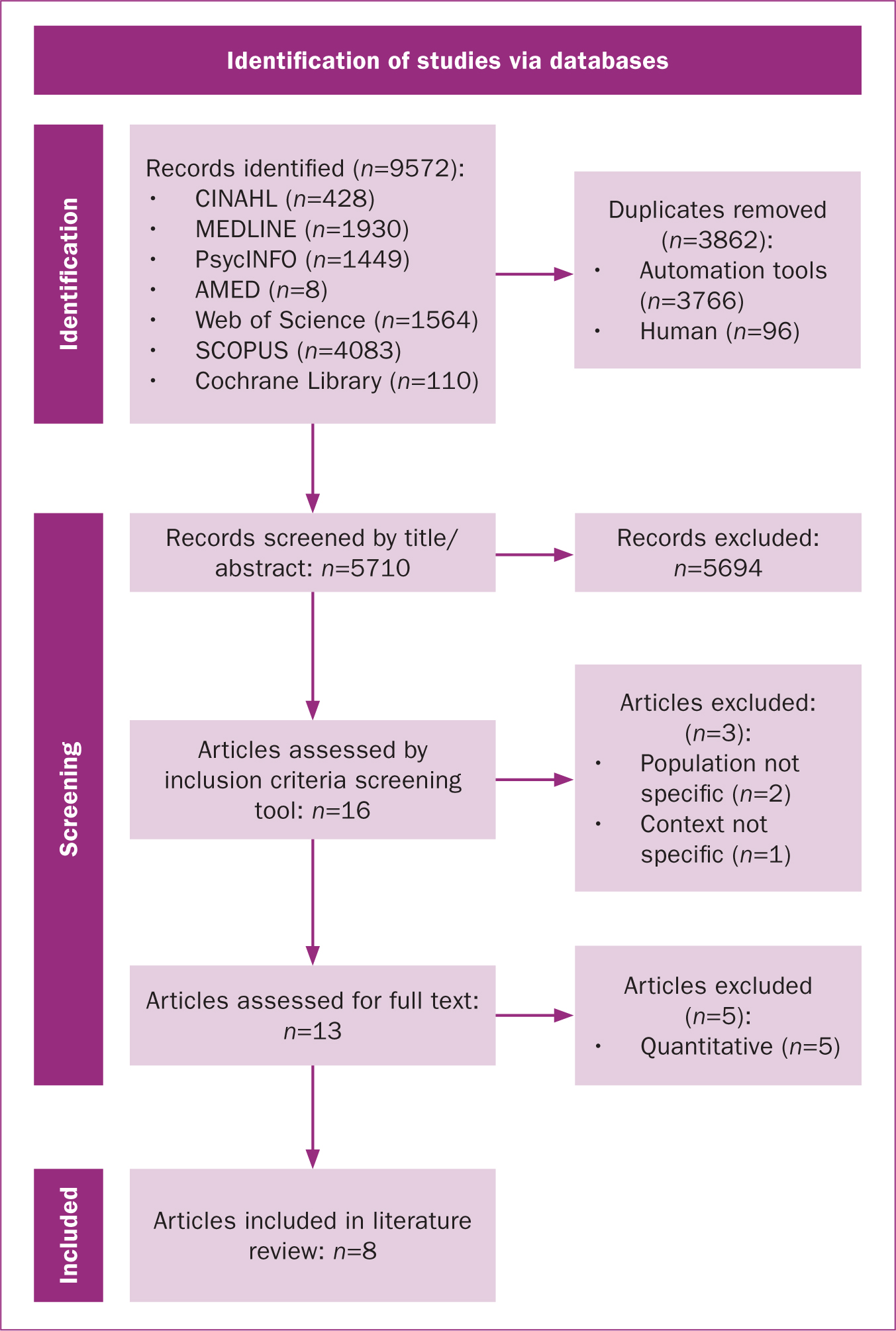

Citation tracking of identified articles was conducted as an additional search strategy using Web of Science via Clarivate and Scopus via Elsevier. Inclusion criteria were applied (Table 1). Database searching identified 9572 records; citation tracking identified no additional articles. Eight studies met the literature review requirements. The identification of studies is illustrated in an adapted PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al, 2021) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Inclusion criteria

| Criterion | Justification |

|---|---|

| Women >18 years old | Legally an adult, more likely to have received ethical approval |

| Professionally or self-diagnosed with autism | Area of interest |

| Seeking women's experiences of pregnancy, birth and immediate postnatal period | Area of interest is qualitative research; quantitative research will be excluded |

| Published in a country with similar demographic and economic factors as UK | For transferability of findings |

| Primary or secondary research study | Possible lack of primary research. Grey literature excluded because the possibility of balancing views and reducing publication bias may be outweighed by the time required to search (Paez, 2017) |

| Peer reviewed literature | High quality studies |

| English text | Pragmatic reasons |

| Full text available | Pragmatic reasons |

| Studies since November 2009 | Year of Autism Act |

All eight studies were assessed against the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2022) checklist and were included in the six-phase thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), with less weight placed on the lower quality studies.

Results

All studies gained ethical approval, were published in peer reviewed journals and were primary research studies, with the exception of Gardner et al (2016), which was a secondary analysis of a qualitative dataset that evolved during the process of developing a research questionnaire. The eight qualitative studies included 124 autistic participants from six countries. Approximately 46% of the total sample was from the UK, 37% from the USA, 4% from Australia and 2% from both Ireland and New Zealand, with 8% not having a country stated.

Thematic analysis revealed three themes (Table 2):

- Low rates of diagnosis and reluctance to disclose diagnoses to maternity healthcare professionals

- Communication and interaction difficulties with:

- How healthcare professionals interpret autistic women's needs

- Autistic women's experiences of interaction with their babies

- Challenges of group education classes

- Sensory difficulties.

Table 2. Themes and subthemes

| Source | Themes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autism diagnosis and disclosure | Communication and interaction difficulties | Sensory difficulties | |||||

| Healthcare professionals | Babies | Groups | Antenatal | Intrapartum | Postnatal | ||

| Gardner et al (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rogers et al (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Donovan (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Lewis et al (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Talcer et al (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hampton et al (2022b) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hampton et al (2022c) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Wilson and Andrassy (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

Diagnosis and disclosure

This theme focused on whether women were aware that they were autistic at the time they had their children, either from professional or self-diagnosis, and whether these diagnoses were disclosed to healthcare professionals. Only two of the eight studies clearly reported whether study participants had been professionally diagnosed as autistic by the time they had their children. Gardner et al's (2016) study included eight participants with Asperger Syndrome (the term used in the study), two of whom had a professional diagnosis prior to having their children, with a further three being self-diagnosed. Rogers et al (2017) conducted a case study of one woman who was professionally diagnosed as autistic prior to pregnancy.

In the remaining six studies, it was unclear whether women had been professionally or self-diagnosed as autistic by the time they had their children. Women were reported as having had a ‘self-report’ of autism (Hampton et al, 2022b) and being ‘with or without a diagnosis’ in Hampton et al's (2022c) comparative study of autistic and non-autistic women; for both studies, this could mean that women were either self or professionally diagnosed. Lewis et al (2021) reported that five of their 16 participants were ‘aware’ that they were autistic at the time of their child's birth, while Donovan (2020) reported that ‘some participants were unaware of their diagnosis at the time of their child's birth’ without providing any further details or whether other participants had been professionally diagnosed. Talcer et al (2021) stated that all seven participants, who lived in the UK, were ‘undiagnosed’ at time of having children, which suggests that they were not professionally diagnosed, but could mean some were aware through self-diagnosis. Wilson and Andrassy (2022) did not state whether their 23 participants were aware that they were autistic at the time they had their children, either by self-diagnosis or professional diagnosis. Among the total sample of 124 autistic participants in the eight studies, only three women had received a professional diagnosis of autism by the time that they had children.

Some women with an autism diagnosis (either professional or self) chose not to disclose their diagnosis to healthcare professionals when they were pregnant (Gardner et al, 2016; Donovan, 2020; Lewis et al, 2021; Hampton et al, 2022b), primarily because they were fearful of negative reactions (Hampton et al, 2022b) and believed healthcare professionals would not understand their needs (Gardner et al, 2016).

For women who did disclose their diagnosis, few felt that this led to their needs being met. Examples of useful accommodations that could have been given included having been provided with the same midwife as much as possible, provision of a single room (Hampton et al, 2022c) and asking permission before touching one woman (Lewis et al, 2021). Most women did not feel that disclosure of their autism was helpful, reporting that this was met with disbelief (Hampton et al, 2022b), overlooked or dismissed by healthcare professionals (Hampton et al, 2022c). These women linked healthcare professionals' responses to a lack of autism awareness (Hampton et al, 2022c) and knowledge, which resulted in adjustments not having been made and needs not being met (Hampton et al, 2022b). When professionals did have good autism knowledge, this tended to be because of personal connections rather than professional training (Hampton et al, 2022c). In some cases, referrals to social services were made, which may have been the result of misunderstandings because of healthcare professionals' lack of knowledge (Hampton et al, 2022b, c).

Communication and interaction difficulties

One of the main characteristics of autism is difficulties with social interaction and communication, so it is perhaps not surprising that this was an area of difficulty. This theme included miscommunications between women and healthcare professionals, including some communication adjustments that women reported that they required, interaction difficulties with their babies and difficulties attending group classes.

How healthcare professionals interpret autistic women's needs

While one study positively reported that some autistic women had felt that the healthcare ‘professionals listened to their concerns and requests’ (Hampton et al 2022c), all studies highlighted that women faced difficulties when communicating and interacting with healthcare professionals. These interactions often influenced how women viewed and processed their birth experiences (Donovan, 2020; Lewis et al, 2021). Difficulties included uncaring healthcare professionals ignoring their wishes (Lewis et al, 2021), not listening (Talcer et al, 2021), dismissing their concerns (Hampton et al, 2022c) and women being ‘concerned about their nurses' perception of them’ (Wilson and Andrassy, 2022). Autistic women, particularly those without previous birth experience, were unsure what information they needed to share or how they should act, struggled to understand humour, took things literally and felt that healthcare professionals had misconceptions about them because of their literal, direct and blunt style of speech, which caused stress and upset (Donovan, 2020).

Women faced difficulties communicating pain to healthcare professionals in pregnancy (Hampton et al, 2022b), labour (Gardner et al, 2016; Donovan, 2020; Lewis et al, 2021; Hampton et al, 2022c) and while breastfeeding (Wilson and Andrassy, 2022). Pain complaints were ignored, minimised or not believed because women appeared ‘calm and subtle even when they were in distress’ (Lewis et al, 2021). Women reported feeling uncomfortable expressing their emotions, resulting in their tone and facial expressions not accurately reflecting their pain, leading healthcare professionals to perceive the pain as less severe (Donovan, 2020; Wilson and Andrassy, 2022).

Difficulties in processing verbal information from healthcare professionals (Hampton et al, 2022b) meant that women required more processing time (Donovan, 2020; Hampton et al, 2022b) especially if they needed to respond (Donovan, 2020; Lewis et al, 2021) or if the professional was providing verbal information prior to commencing a procedure (Donovan, 2020). Processing difficulties meant they found telephone calls with healthcare professionals difficult and preferred face-to-face, email or text communication (Hampton et al, 2022b). Many women needed information to be given in small amounts, repeated several times (Donovan, 2020; Lewis et al, 2021) and/or written down (Hampton et al, 2022b). Extra time in appointments was beneficial (Hampton et al, 2022b). Specific questions from healthcare professionals were preferred rather than open ended questions, which were more difficult for them to answer (Hampton et al. 2022b, c).

Antenatally, women required clear and information including ‘what to expect in appointments and who they would see’ (Hampton et al, 2022b). During childbirth, they needed clear, direct information, with responses to their questions stated clearly (Hampton et al, 2022c), and postnatally, they wanted to be informed in advance what time healthcare professionals would be visiting their home (Hampton et al, 2022c). Healthcare professionals' not understanding that women needed more time to process information sometimes ‘led to a breakdown in communication, resulting in a lack of trust’ (Donovan, 2020). Women in two of the UK-based studies reported that continuity of carer was beneficial at relationship building to enable needs to be met (Hampton et al, 2022c) and for facilitating trust and understanding (Hampton et al, 2022b).

Interaction with their babies

Women reported experiencing delayed emotional connections (Gardner et al, 2016; Lewis et al, 2021; Talcer et al, 2021), which were explained as either the result of women's autistic traits (Garner et al, 2016; Talcer et al, 2021) or the result of trauma around the birth, which was the result of their autistic needs not having been met (Lewis et al, 2021). Women also had difficulties understanding their babies' behaviours and facial cues, with facial expressions causing confusion (Gardner et al, 2016), as well as difficulties knowing how to play with their babies and being able to manage their unpredictable nature, which disrupted their routines (Hampton et al. 2022c). Increased anxiety was reported as they were no longer able to withdraw and have alone time to recharge, which was a coping strategy prior to having had a baby (Talcer et al, 2021). Positively, autistic women reported additional parenting strengths such as ‘persistence and empathising with their baby's sensory needs’ and being good at interpreting the noises that babies make (Hampton et al, 2022c) as they were ‘sensitive to sounds’ (Gardner et al, 2016).

Challenges of group education classes

Women encountered challenges in group classes both antenatally (Hampton et al, 2022b) and postnatally (Gardner et al, 2016; Talcer et al, 2021; Hampton et al, 2022c), as well as with breastfeeding support groups, which were described as ‘challenging’ (Hampton et al, 2022c) and ‘overwhelming’ (Talcer et al, 2021) because of the social aspect of the groups (Hampton et al. 2022b). Smaller, one-to-one or online antenatal classes were preferable (Hampton et al, 2022b) and online or in-person peer support was beneficial (Talcer et al, 2021; Hampton et al, 2022c), as they ‘could be open about how they were feeling, not feel judged and develop a positive identity as an autistic mother’ (Talcer et al, 2021).

Sensory difficulties

This theme explored the sensory difficulties that women experienced in the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods, which were reported in all studies. Women experienced heightened sensory issues during pregnancy (Gardner et al, 2016; Rogers et al, 2017; Talcer et al, 2021; Hampton et al, 2022b). Hampton et al (2022b) identified that while both autistic and non-autistic women experienced changes in their sense of smell and taste, only autistic women frequently reported sensory changes in sound, light and touch, a finding consistent with other studies reporting altered senses of light, sound (Gardner et al, 2016) and touch (Gardner et al, 2016; Rogers et al, 2017). Increased awareness of internal sensations during pregnancy was also reported (Gardner et al, 2016; Talcer et al, 2021), along with difficulties adjusting to rapid changes in body size and shape (Hampton et al, 2022b), suggesting challenges with interoceptive and proprioceptive senses.

In the birth environment, women reported problems with bright lighting (Gardner et al, 2016; Talcer et al, 2021), sounds, smells (Gardner et al, 2016; Lewis et al, 2021), hearing (Talcer et al, 2021) and touch (Rogers et al, 2017). The combination of labour pain and heightened sensory stimulation overwhelmed some women, preventing them from advocating for themselves fully (Donovan, 2020), and causing discomfort, trauma, non-verbal episodes, dissociation during birth (Lewis et al, 2021) or autistic meltdowns (Hampton et al, 2022c). Some women used self-stimulating behaviours during labour, such as ‘rocking, swaying, humming or hand flapping’ (Simone, 2010, cited in Donovan, 2020) to help calm themselves, but these behaviours were often misunderstood by healthcare professionals (Donovan, 2020). To avoid the expected challenging sensory environment of hospitals, some women expressed a preference for giving birth in a birth centre or having a home birth (Hampton et al, 2022b).

Breastfeeding presented specific sensory challenges with skin to-skin contact and the baby crying (Talcer et al, 2021; Wilson and Andrassy, 2022) causing high levels of stress, anxiety and overwhelm for many women (Talcer et al, 2021). Despite these challenges, most continued breastfeeding because they felt it was best for their baby (Gardner et al, 2016; Talcer et al, 2021, Wilson and Andrassy, 2022).

Discussion

Autistic women face many challenges during the pregnancy–childbirth continuum, including low rates of professional diagnoses, lack of awareness about autism, difficulties in communicating and interacting with healthcare professionals, babies and groups, as well as sensory difficulties. Two UK studies have highlighted the benefits of continuity of carer for autistic women (Hampton et al, 2022b, c), but the national shortage of midwives creates an environment where provision of many continuity of carer models are no longer viable (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022).

In England, midwives have a professional duty to identify and reach out to ‘women who may find it difficult to access services’, and to adapt ‘care provision to meet their needs’ (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2019). Midwives also have a legal duty to provide reasonable adjustments (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2019) to women with disabilities, including autism. However, when women are unaware of their autism, it can be challenging for midwives to recognise the need to make reasonable adjustments. This is also true if women choose not to disclose their autism, which was reported by studies included in this literature review and elsewhere (Lum et al, 2014; Pohl et al, 2020; Doherty et al, 2022; Hampton et al, 2024).

While not all women will want to perceive or pursue a diagnosis of autism for themselves, it is also not for a midwife to ‘diagnose or label’ a person as autistic. For any healthcare professional interacting with another person, it is important to be sensitive, kind, considerate and compassionate during individual, person-centred interactions incorporating individual values and beliefs as a ‘normalised’ approach to care (Kitson-Reynolds, 2022; Kitson-Reynolds and Ashforth, 2022).

The present review found that some women who disclosed their diagnosis found that their needs were not met, which they attributed to healthcare professionals' lack of awareness and knowledge. Despite the existence of an autism-specific Act of Parliament in England since 2009, there was no legal requirement for autism training among NHS staff until 2022. At this time, the Oliver McGowan mandatory training in learning disabilities and autism (Health Education England, 2023) became law in England. The training was launched on 1 November 2022 and is now a legal requirement for all health and social care staff, including midwives (Local Government Association, 2023). This represents a significant achievement and a positive step forward for autism and autistic individuals. However, the training is not specific to maternity and English maternity services lack maternity-specific autism training and policies (King, 2022), highlighting the need for maternity autism guidelines and maternity autism leads (Fox, 2022). An online survey by King (2022) revealed that 81% of patient-facing maternity staff in England reported not receiving any autism training since starting their role, supporting the beliefs expressed by autistic women in this literature review.

Some organisations with links to midwifery have been proactive about increasing autism knowledge and understanding. For example, the University of Southampton's Faculty of Health Sciences has an interactive online e-learning package for their pre-registration midwifery students (Kitson-Reynolds et al, 2015) and a ‘values based enquiry’ journey (Kitson-Reynolds 2022; Kitson-Reynolds and Ashforth 2022) that incorporates inclusivity in the pre-registration ‘autism friendly’ midwifery curriculum (Kitson-Reynolds, 2022). The Royal College of Midwives (2021) also offers a 30-minute online session on autism and pregnancy for its members. NHS England (2023) recently launched its equality, diversity, and inclusion improvement plan to address discrimination and prejudice, although this is currently only for staff, with the aim of improving their experience, not patients accessing the health service.

Previous systematic reviews have reported on the sensory challenges of autistic women during pregnancy and birth (Samuel et al, 2022) as well as autistic women's experiences of infant feeding (Grant et al, 2022). The present literature review is the first to report on the experiences of autistic women in the antenatal, intrapartum and early postnatal periods, to identify what midwives in England can learn from studies.

While all eight studies acknowledged that the participants had expressed communication challenges, many did not consider their autistic participants' communication and interaction preferences during the research. Lewis et al (2021) stated that online written interviews had been chosen to meet the communication needs of their autistic participants and, while some studies offered various interview formats, such as remote, in-person, video calls or Facebook messenger (Donovan, 2020; Hampton et al, 2022b, c; Wilson and Andrassy, 2022), only Wilson and Andrassy (2022) stated that these had been carefully considered for their autistic participants. Donovan (2020) explained that two of their 24 participants specifically requested use of Facebook messenger to ‘decrease the anxiety they typically experienced in social situations’. However, this autism friendly data collection method was later identified as a limitation because the ‘online format used did not allow the researcher to fully appreciate the participants' emotions and potentially affected the researcher's understanding’ (Donovan, 2020). Hampton et al (2022c) expressed a similar concern about their two participants who provided responses via email, noting that it might have ‘influenced the data for these two participants’. For example, they ‘may have given less spontaneous responses than would be possible through spoken communication’. It is crucial for future research to fully consider the preferred communication styles of autistic people, especially when designing data collection methods, to ensure that the needs of autistic participants are fully met.

Recommendations

Midwives must be aware of the specific challenges faced by autistic women in the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods, which can lead to negative experiences for these women. During the initial ‘booking’ process for maternity care, midwives must specifically ask whether women identify as autistic or neurodiverse. Simply asking a woman if they have disabilities and/or mental health issues is unlikely to encourage disclosure of an autism diagnosis, whether professional or self-diagnosis (Kitson-Reynolds et al, 2015). As for all women, there is a need for an individualised plan of care and a consideration of reasonable adjustments to enhance inclusive care for all, regardless of perceived need made by an individual healthcare professional. The midwife's role is to support and advocate for women throughout the childbirth continuum, ensuring a safe outcome for all, and by any member of the multidisciplinary team they may come into contact with (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015).

In education, implementation of the ‘decolonising midwifery’ education toolkit (Royal College of Midwives, 2023) will ensure that all newly validated midwifery programmes will be cognisant of all areas of equality, diversity, inclusivity and belonging, including neurodiversity, and will be monitored via the Nursing and Midwifery Council (2019) standards.

The literature review identified only eight qualitative studies, highlighting the scarcity of published qualitative studies worldwide. Further research is required in England to assess the impact of the Oliver McGowan mandatory training on the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal experiences of autistic multiracial women, as well as the predominantly female maternity workforce who may themselves have a neurodiversity. While increased autism knowledge and awareness among healthcare professionals could improve many of the difficulties experienced by autistic women, areas such as communicating pain and interacting with their babies may require further research as these areas are unlikely to change solely through increased autism knowledge and awareness.

Limitations

This literature review was part of a Master's degree and so was conducted by one researcher, which may affect trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). It was also restricted by time, resulting in the inclusion of only peer-reviewed, published articles, which may have caused publication bias. While a carer to an autistic family, the first author does not consider themselves autistic, so lacks complete ‘insider’ status (Braun and Clarke, 2013), which may impact the interpretation and application of results. The literature review did not include any autistic women with learning disabilities, so the findings may not be transferable to this subgroup of autistic women.

Conclusions

Overwhelmingly, this review identified that autistic women experience difficulties during the pregnancy and childbirth period, outside of their routines and ‘normal’ life. Based on the findings, midwives must treat all women as individuals, asking about their specific needs and any adjustments that can be made to provide inclusive care. There is a great deal that midwives can learn from women who have a diagnosis of autism and those who may present with associated characteristics. Education can be the starting point for effective practices to enhance the experiences for all women.

Key points

- Rates of professional autism diagnosis are currently low among women of childbearing age.

- Some autistic women may be self-diagnosed, others will be unaware they are autistic.

- Autistic women may be reluctant to diagnose their autism to healthcare professionals.

- Autistic women experience many difficulties during antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods, including communication and interaction difficulties with healthcare professionals, babies and groups, and heightened sensory issues, with maternity environments often not suited to their needs.

CPD reflective questions

- What percentage of women are currently diagnosed as autistic in your clinical caseload?

- What barriers do autistic women face in your clinical environment?

- How would you support a woman in your care who disclosed that she believes she is autistic or that she has a professional diagnosis of autism?

- What reasonable adjustments might you need to consider making for an autistic woman in your care?

- What is your maternity unit policy for autistic women and how does it meet the needs of the clinical staff and women in your area of maternity service provision?