Historically, black African women in the UK have an increased risk of dying in childbirth, compared to other ethnic minority groups, a phenomenon that has been noted since 2000. This has been related to recent migration and poor or no engagement with antenatal care and (Table 1) (Cantwell et al, 2011; Knight et al, 2016; Office for National Statistics, 2016; Knight et al, 2017). There have been assumptions made in maternal mortality reports that culture is a relevant quality in determining black African women's use of antenatal services in the UK (Cantwell et al, 2011; Knight et al, 2016; Office for National Statistics, 2016; Knight et al, 2017); however, these cultural qualities have not been defined. Before 2000, maternal mortality reports grouped black African, black Caribbean, black Other and black Mixed women together for the Office for National Statistics codes. However, in the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report for 2000-2002, black African women were audited separately as they had the greatest risk for maternal deaths: 72.1 per 100 000 maternities compared to 10.7 per 100 000 for white women (Lewis and Drife, 2004).

| Year | Deaths among Black African women | Countries of birth | Estimated maternal mortality rate per 100 000 maternities | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % born outside UK | Black African women | White women | |||

| 2000–2002 | 30 | 33 | Not provided | 72.1 | 10.7 | Lewis and Drife, 2004 |

| 2003–2005 | 35 | 89 | Nigeria, Somalia, Ethiopia and Francophone countries | 62.4 | 11.1 | Lewis, 2007 |

| 2006–2008 | 28 | 68 | Only Nigeria mentioned as main country of origin for health tourism | 32.8 | 8.5 | Cantwell et al, 2011 |

| 2009–2012 | 28 | 50 | Mainly Nigeria, Somalia and Ghana | 26.9 |

9.0 | Knight et al, 2014 |

| 2013–2015 | 19 | 47 | Mainly Nigeria, Somalia and Democratic Republic of Congo | 28.2 |

6.6 | Knight et al, 2016; 2017 |

Antenatal care, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), should consist of a booking appointment at less than 10 weeks' gestation and no missed antenatal appointments (Knight et al, 2014). Maternal mortality and a history of poor or no antenatal care in black African women has continued to be prevalent (Table 1) (Knight et al, 2016; 2017).

Black African women who have migrated into the UK within the past 4 years have been found to be at a higher risk for maternal mortality; suggestions for these findings have been vague and mortality reports have stated that this may be due to cultural factors implied in ethnicity with no further explanation provided (Lewis, 2007; Cantwell et al, 2011; Knight et al, 2016). The majority of the black African women who died due to childbirth and pregnancy between 2003-2015 had recently migrated from Nigeria, Somalia, Ethiopia and Ghana and some Francophone countries (Lewis, 2007; Knight et al, 2014; 2016; Nair et al, 2016; Knight et al, 2017).

Maternal morbidity and infant mortality

An inability to access antenatal care also leads to increased infant mortality in ethnic minority women (Department of Health, 2010a; Bunn, 2016). Maternal death resulting in death of the fetus is known to affect the educational and economic status of surviving children (Cantwell et al, 2011; Hunt and Bueno de Mesquita, 2010; World Health Organization (WHO), 2016). Gray et al (2009) have suggested that a complex mix of deprivation, behavioural and cultural factors leads to a higher risk of infant death among black and other ethnic minority groups. In addition, the odds of severe maternal morbidity are 83% higher for black African women throughout all stages of pregnancy, compared with white European women (Nair et al, 2014a). The United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System conducted a case study of 1753 women between February 2005 and January 2013, finding that inadequate uptake of antenatal services doubled a woman's risk of maternal morbidity, which was noted to be higher among black African women. Other factors included a lack of information, language barriers or cultural differences (Nair et al, 2014a).

The importance of culture in antenatal care

Culture is a set of guidelines that individuals inherit as members of a particular group, which influences how they view the world emotionally, and their behaviour in relation to other people and the natural environment (Helman, 2007). Individuals do not need to be located in a particular place for a culture to be maintained, as long-standing traditions, beliefs and practices pass down from generation to generation. Culture is therefore sustained provided there is an individual to continue these practices. Acculturation refers to the process of cultural and psychological change that occurs when two cultures meet (Sam and Berry, 2010); this may be a mixing of cultures or a dominance of one culture over another. However, one cannot assume that acculturation occurs for all migrant African women and, if so, to what extent.

Awareness of how culture, tradition and acculturation may affect black African women's health-seeking behaviour is the first step in understanding cultural behaviour (Esegbona-Adeigbe, 2011). Culture has three levels: a tertiary level that is visible to the outsider, such as traditional dress and foods; a secondary level of underlying rules and guidelines not generally relayed to outsiders, including taboos and rituals relating to behaviour (Hall, 1984); and a primary level of culture, namely rules that are known and obeyed by all and may be almost unconsciously performed. This level is more stable and the most resistant to change (Hall, 1984). Examples of this include inherent respect for elders, family and community; and culturally acceptable methods of communication. The primary level of culture presents a challenge in the provision of health services as cultural unawareness may create unseen barriers.

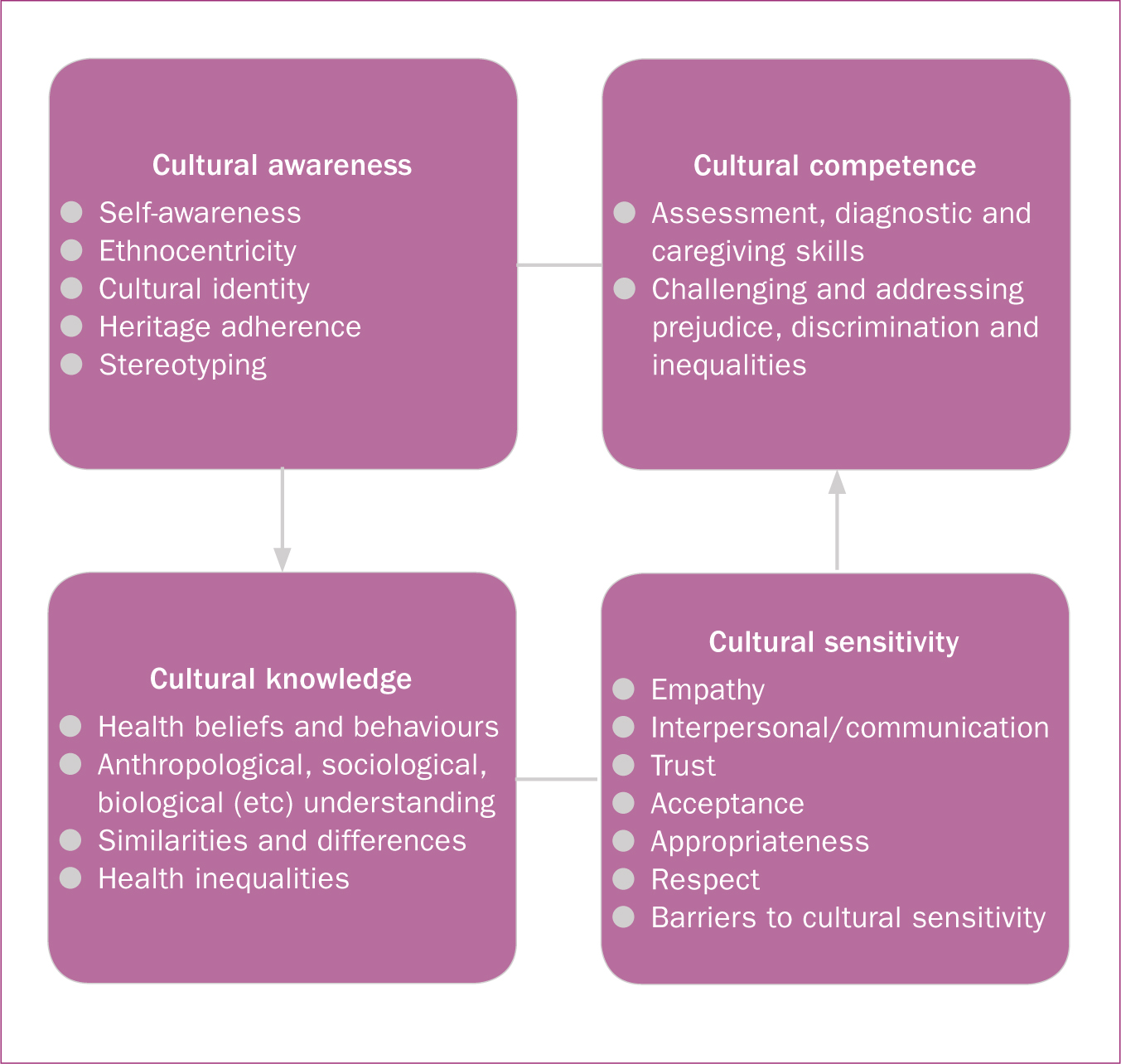

According to O' Hagan (2001), cultural competency is an ability to maximise sensitivity and minimise insensitivity in health services, which may increase engagement with antenatal care for black African women. Papadopoulos (2006) states that the capacity to provide effective healthcare relies on considering people's cultural beliefs, behaviours and needs, which results in cultural competency. A model for developing cultural competency created by Papadopoulos et al (1998) to provide effective health care (Figure 1) consists of three factors: cultural awareness, cultural knowledge and cultural sensitivity. This model provides a basis to explore any cultural qualities in antenatal care provision and will be used during this literature review.

National guidance on cultural qualities in antenatal care

Historically, national policies have supported the recommendations from maternal mortality reports to cater for ethnic minority women and increase access to maternity services with an emphasis on cultural needs. This included Sure Start clinics, which provided easier access to health advice and self-referral for midwifery care (Department of Health 2004; 2007; 2010b). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) maternity care guidelines focused on women with social needs, encouraging cultural sensitivity to motivate vulnerable and hard-to-reach women to engage with maternity services (RCOG, 2008). NICE guidelines were developed for women with complex social factors, including recent migrants, as women still did not understand the healthcare system and reported lack of cultural sensitivity from providers (NICE, 2010). However, despite national policies and guidance on the importance of cultural qualities in maternity care, the National Maternity Review (2016), commissioned to improve choice and safer care for women, demonstrated that women still reported dissatisfaction with maternity services. Women from different backgrounds felt that health professionals needed to understand and respect their cultural and personal circumstances (National Maternity Review, 2016).

Literature review

Aim

The aim of this literature review was to explore the cultural qualities relevant in antenatal care for black African women.

Method

A literature search was conducted on the CINAHL Plus, Medline, POPLINE, PubMed, Cochrane and Scopus databases with a date range from January 2000 to August 2017, to capture the first noted increase in mortality for black African mothers in the UK (Lewis and Drife, 2004). Studies conducted nationally and internationally were included in this review; however, this was limited to articles published in English. All abstracts and studies regardless of methodology were included. The key search terms used were ‘black African’, ‘women’, ‘pregnant’, ‘maternal health services’, ‘culture’ and ‘competency’. Articles were selected for this review if they included any experiences reported by black African women on routine antenatal care and findings suggesting that cultural qualities played a role. In addition, any studies involving experiences of antenatal care providers caring for black African women were also selected if cultural qualities were identified as being relevant to service provision. A total of 16 studies were considered to be relevant to this review.

Findings

Globally, studies on black African women living in the diaspora and their indigenous countries have highlighted the importance of cultural qualities in antenatal care provision. The studies reviewed showed that black African women's use of antenatal care services was associated with certain cultural beliefs and practices. Lack of cultural competency and sensitivity of health services, as well as non-cultural factors such as lack of reproductive knowledge and how to negotiate the health system, led to women's dissatisfaction with antenatal care.

Cultural beliefs and practices

Systematic reviews looking at migrant black African women's use of pregnancy care suggested that reduced antenatal care attendance was influenced by sociocultural factors, beliefs and behaviours, such as use of traditional medicine and pregnancy taboos (Carolan 2010; Heamen et al, 2013; Nair et al, 2014b; 2016). Studies also showed that engagement with antenatal care was affected by cultural beliefs and practices for migrant black African women in developed countries. A qualitative study conducted by Carolan and Cassar (2010), involved interviews with 18 recently arrived pregnant African women in Australia to discover their antenatal care experiences, concluding that their expectations in care were mediated by cultural beliefs. The women in this study were mainly from the horn of Africa, so cultural views relayed by these women may differ from other black African women.

Similar findings were found in a study by Brown et al (2010), which explored sources of resistance to common prenatal and obstetric interventions in 34 migrated Somali women in New York (migration period 1-7 years). The authors used individual interviews and focus groups, and concluded that educating health professionals about Somali cultural practices and fears for childbirth would reduce resistance. The strengths of this study were the use of key informants from the Somali community through the data collection phases and analysis, and a focus group to check validity of overall themes. Another study (Mohale et al, 2017) explored the experiences of women who had given birth in sub-Saharan Africa and Australia (migration period 1.5-10 years). The authors found that women's maternity needs were also shaped by sociocultural norms. It was also acknowledged in this study that, regardless of place of birth, women valued being treated with dignity and respect, and that improving health literacy and communication were as important as cultural sensitivity.

A UK study also found similar issues to global studies around cultural beliefs and practices. In one study in Newham, London, routinely collected electronic patient data was used to predict the timing and initiation of antenatal care in an ethnically diverse group of women (Cresswell et al, 2013). This study indicated that the risk of late booking for black African women compared to white women was higher (Cresswell et al, 2013), and that sociocultural factors, including poor English, played an important role in initiation of antenatal care. The length of time that the women had been in the UK was not provided. The limitation of this study was that information was self-reported and there was no confirmation of women's answers; however the large number of African women involved (n=3195) increased the credibility of the link between ethnicity and late booking.

Four studies were found that explored maternal satisfaction of black African women in their indigenous countries and found that cultural beliefs and traditions also played an important role in antenatal care attendance. Mathole et al (2005) used focus groups and individual interviews to describe the perspectives and expectations of antenatal care in 44 Zimbabwean women. They found that the importance of understanding different perspectives and cultural beliefs had a great influence on use of services. Interestingly, this study also involved the 24 men in separate focus groups; however, it is unclear if there was any relationship between the men and women and how this may have affected the women's views. Another study in South Africa used semi-structured interviews to explore the beliefs and practices that influenced 12 women's attendance at antenatal clinics for the first time. The results showed that indigenous beliefs and practices affected attendance and the authors concluded that this knowledge should be incorporated into midwifery training curricula (Ngomane and Mulaudzi, 2012). Igboanugo and Martin (2011) also reported that women's satisfaction was increased when traditional and spiritual methods were incorporated into maternity care. Their exploratory study was with eight pregnant Nigerian women in the Niger Delta, and was conducted using semi-structured interviews. Serizawa et al (2014) found in a study involving six Sudanese village women that culture influenced their health-seeking behaviour during pregnancy and that understanding their cultural perceptions was imperative to meet their needs.

Cultural competency and sensitivity

Studies showed that antenatal care provision needed to consider the cultural views of black African women to achieve cultural competency/sensitivity (Murray et al, 2010; Stapleton et al, 2013). In Ireland, a structured approach to narrative enquiry aimed to gain insight into the experiences of 22 migrant women (14 from Nigeria), who were pregnant and seeking asylum (Tobin et al, 2014). The authors found inadequate, poorly organised maternity services and lack of staff training in cultural competency, and recommendations included further research into antenatal care and childbirth education needs (Tobin et al, 2014). The women in this study were going through the asylum process and so were extremely vulnerable, which may have affected their expectations and experiences of pregnancy care. Degni et al (2014) conducted five focus groups involving 70 Somali-born women in Finland to explore their experiences of antenatal care and found that their perceptions were important for health professionals to achieve culturally competent antenatal care. Length of time in Finland was not provided in this study; however, the large sample size lends strength to the findings.

The influence of cultural insensitivity is also reported by Garcia et al (2015) who conducted a scoping review of 1701 papers, concluding that there was a lack of practice interventions aimed specifically at addressing culturally competent maternity services and sharing best practice for black African and minority ethnic women. Another study on the perceptions and views of 35 migrant women, including black African women, in Australia used focus groups to explore their sociocultural barriers and health needs during pregnancy (Renzaho and Oldroyd, 2014). The need to reconcile practices and expectations between different cultures and Australian norms were suggested to test culturally competent interventions that addressed health and lifestyle needs in migrant women (Renzaho and Oldroyd, 2014). The focus groups were arranged according to language spoken, and three African women (migration 3-5 years) were in one focus group; however, it was not clear as to which specific cultural practices related to this group.

In a qualitative interview study of a diverse group of 27 women who booked in South Yorkshire after 19 weeks' gestation, Haddrill et al (2014) found that a complex relationship of beliefs and behaviours, combined with lack of reproductive knowledge, contributed to delayed access to maternity care. The sample only included one black African woman, so relevance of findings to other black African women is limited. However, it is important to note the complex mix of cultural and non-cultural factors in this study and how these affected women's experiences and health-seeking behaviour.

Ethical approval was sought for all of the studies selected for this review with consent obtained from participants, although it was unclear how ethical standards were maintained in most of the studies, particularly when dealing with vulnerable groups of migrant women. The participants used in all the studies represented the research well and most of the studies provided their characteristics and information on how the sample was selected, providing reliability, validity and possibility of replication (Ryan et al, 2007).

Strengths and limitations

In all of studies, details of the data collection methods and data analysis were provided, which was useful in determining if there was any potential bias. Data collection methods used in the most of studies were appropriate, as women and service providers were asked directly about their experiences of care received during pregnancy either through interviews, questionnaires or focus groups. One study used electronic patient data (Cresswell et al, 2013), resulting in no member-checking, whereas a combination of member-checking, independent analysis of results and use of two researchers for data analysis reduced bias in other studies (Brown et al, 2010; Igboanugo and Martin, 2011, Ngomane and Mulaudzi, 2012; Haddrill et al, 2014; Tobin et al, 2014), which was important in ensuring reliability of the results.

In some studies, there was potential for bias with the recruiter being known to the woman, use of interpreters to recruit women and the use of snowballing (Mathole et al, 2005; Brown et al, 2010; Igboanugo and Martin, 2011; Ngomane and Malaudzi, 2012; Tobin et al, 2014; Mohale et al, 2017). This raised the question of whether some hard-to-reach women were not adequately represented. However, the findings in a majority of the studies provided enough illustrative samples of data to enable the reader to determine if the study recommendations had been appropriately drawn from the data analysis (Mathole et al, 2005; Brown et al, 2010; Carolan and Cassar, 2010; Murray et al, 2010; Igboanugo and Martin, 2011; Ngomane and Mulaudzi, 2012; Haddrill et al, 2014; Renzaho and Oldroyd, 2014, Tobin et al, 2014). Unfortunately, limitations regarding language barriers, loyalties to clinical staff influencing women's disclosures about aspects of services they disliked, difficulties in sharing experiences in focus groups and small sample size were clearly presented in only a few studies (mostly in Western settings) (Brown et al, 2010; Mohale et al, 2017; Murray et al, 2010; Stapleton et al, 2013).

Discussion

The aforementioned studies and systematic reviews demonstrate a subjective, complex mix of several factors intertwined with culture that may impact on adequate uptake of antenatal care and possibly leading to an increased risk of maternal mortality and morbidity.

This literature review revealed that cultural qualities has some impact on women's satisfaction with antenatal care; therefore this is a key impediment to care uptake by black African women. Interestingly, cultural qualities arose whether black African women were living in their indigenous country or the diaspora. These studies also highlighted the importance of cultural qualities in antenatal care for black African women regardless of the length of time in their new country.

It is noted that other, non-cultural qualities may have influenced black African women's engagement with antenatal care, for example, in studies where a lack of reproductive knowledge and difficulty in negotiating services played an important part in delayed or poor access to antenatal care (Hadrill et al, 2014). Similar issues arose in other studies; however, if access to antenatal care was successful, then cultural qualities appeared to be viewed as highly important. How cultural qualities in antenatal care were described by women was ambiguous: in some studies (Cresswell et al, 2013; Mohale et al, 2017), socio-cultural issues were highlighted as being important to women's satisfaction but the essence of what these constituted were not fully investigated.

Recommendations

Maternity service providers should ensure that cultural considerations to reduce cultural insensitivity and maximise cultural awareness are embedded in antenatal care provision. Midwives should explore a woman's cultural needs at the booking interview and incorporate any specific qualities into the pattern of care devised for the woman (Table 2). Midwives need to have pre-existing knowledge of what these cultural qualities may be and also how they may be explored with women. The problem therefore is where midwives can access this information and also how initial access to care can be improved for these women.

| C | Clarify woman's ethnic origin |

| U | Use this to initiate discussion on cultural norms during pregnancy |

| L | Link this information to routine antenatal care advice e.g. diet, exercise, lifestyle and expectations during pregnancy |

| TU | TUrn culturally specific antenatal advice into a culturally specific care plan |

| RE | REview care plan with woman and incorporate into pattern of antenatal care |

Despite numerous studies highlighting that cultural qualities are an important aspect in antenatal care for black African women, there has been no study that extends this knowledge. Cultural knowledge is an important element of cultural competency and can be used as a stepping stone to cross the gap between midwives and women (Esegbona-Adeigbe, 2011). Further research is needed to explore the cultural qualities expected by black African women during antenatal care, due to their increased risk for maternal mortality (Lewis, 2007; Cantwell et al, 2011; Knight et al, 2014). This knowledge can be used to develop culturally competent and sensitive antenatal care services, which in turn may improve access and engagement, and reduce the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality. The outcomes of any study may provide knowledge on how to effectively assess the cultural needs of black African women, which can be incorporated into midwifery training and education.

Conclusion

The need to manage black African women's expectations of cultural qualities during antenatal care provision has been highlighted in this literature review. Although there are other factors that may affect black African women's access and engagement, cultural sensitivity, cultural competency, and respect for sociocultural norms are qualities desired by black African women when asked about their views of antenatal care. In addition, lack of cultural qualities has been linked to poor attendance, resulting in poorer pregnancy outcomes for these women. Midwives should be aware of this issue and take steps to ensure that antenatal care provision meets women's cultural needs by exploring women's cultural preferences during the booking interview and incorporating these in to the plan of care. Furthermore, exploration of women's perceptions of what they deem to be culturally sensitive/competent care is required so that findings can be applied in antenatal care provision and midwifery training.