Risk assessment and management is extremely important in midwifery. However, it is unclear how its principles fit with day-to-day clinical midwifery practice. While midwives are the inherent leaders of normality, there are ongoing challenges under the auspices of risk management which instil fear of being blamed when things go wrong, especially around fetal monitoring in labour (The Royal College of Midwives, 2010; Healey et al, 2016).

Risk management, which is the central component of clinical governance, is concerned with improving safety and quality of care (Doherty, 2010). Clinical governance is defined as ‘a framework through which health service organisations are accountable for continually improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care, by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish’ (Department of Health, 1998).

Maternity services in the UK have seen an intensification of risk management strategies in response to adverse outcomes, such as infants born with cerebral palsy which are a growing and serious challenge for obstetricians and midwives. As purported by Jameson (2013), there has been a growing shift within maternity services towards improvement in care; the key driver has been largely focussed on safety. Specialist roles have been created, in the National Health Service (NHS), under the auspices of the risk agenda such as risk midwife/governance midwife, risk/governance manager and lead obstetrician for risk, to manage the worrying trends.

Previously, the focus was on the wrongs done by the individual, following an adverse outcome. According to the NHS Improvement (2018), there has since been a sea-change from a blame culture, to a wider concept of ‘clinical governance’ and the parallel concept of ‘no blame’ moving to ‘a just culture’. A paper by the NHS Resolution ([NHSR], Magro, 2018) demonstrates how midwifery care continues to dominate the proportion of litigation costs to the NHS; £50% of the total value (£4.37 billion) for all specialties’. In their report, the NHSR stated that whilst the volume of claims within maternity directly relating to cerebral palsy/brain damaged babies has decreased, owing to the new model of incident-to-resolution, the focus remains on the safe delivery of maternity care. According to Healey et al (2016), the ‘skewed perceptions of risk have produced a maternity service that focuses solely on safe outcomes, as opposed to optimal outcomes…’

Maternity services have seen a huge shift from general practitioners coming in to hospital to deliver women under the shared care option (Davis, 2013), to the ethos of ‘low’ and ‘high’ risk categorisations of pregnancy, but midwives remain with women from the antenatal to post-delivery period, as the lead care professionals until today (Sandal et al, 2016). This speciality has been facing numerous criticisms for decades, around the dichotomy of normal childbirth versus risk; some asserting that childbirth carries an inherent risk, by virtue of the fact that the outcome is always unpredictable (Davis, 2013).

The suspension of obstetrician Wendy Savage in 1985 created an unprecedented awareness of the issue of risk categorisation in pregnancy, advocating against classifying women as ‘high risk’, but rather treating them as normal (Davis, 2013). This has catapulted into further campaigns and initiatives; influencing national policies, guidelines and recommendations; the focus being heavily placed on risk management from the onset of pregnancy.

As purported by Dahlen (2010), the risk discourse has been amplified with an emphasis on undesirable or poor patient outcomes. This is often interpreted as outcomes which go beyond safe delivery of mother and baby. The absence of an achieved equilibrium between normality and managing risks was further heightened and consequentially propelled into more stringent applications of risk-targeted initiatives, following the release of the report on failings of maternity care at Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust (Kirkup, 2015).

Over the years, confidential enquiries have emerged with reports on cases resulting in poor patient outcomes. Some of these cases have been attributable to a failure to learn lessons and despite the huge pay-out following a fatal drug error (Health and Safety Executive, 2010), incidents of such nature continue in midwifery. Therefore, research is needed to identify the disconnect between the two spectrums; risk management and the reality of midwifery practice in its social context.

Aim

The aim of this literature review is to explore how risk management principles fit with the reality of clinical midwifery practice.

Methods

Search strategy

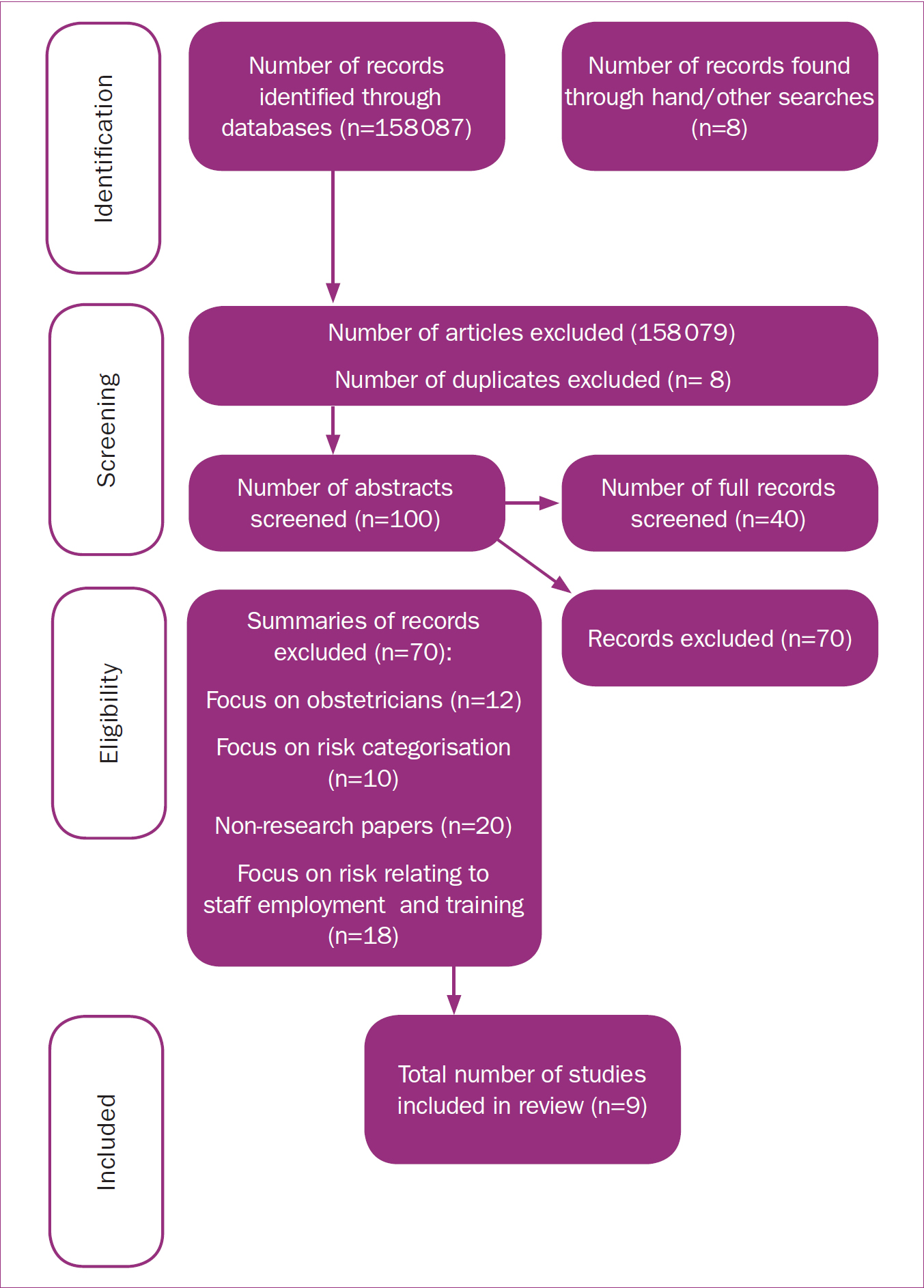

A literature search of a number of databases was undertaken electronically, back-chaining as well as a search by hand. No suitable studies were found for the latter results. The main databases included CINAHL, Pubmed, BNI, Maternity and Infant Care, Medline and Google Scholar. Nine papers met the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The SPIDER tool (Cooke et al, 2012) was used to enable an accurate breakdown of the key aspects of the review question. The searches focussed on articles published/unpublished from January 2008 until April 2019, and was limited to primary research on risk management in midwifery care, written in English language, and included the UK and other countries except America.

The keywords which informed the search were midwives/normality, attitude of midwives, social reality, risk assessment, risk management/governance, patient safety. The author was particularly concerned to maintain a focus on midwives rather than all clinicians. An illustration of the results of the search is found at Figure 1 (Jackimowicz et al, 2015).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Primary research was selected which described risk management in midwifery care from January 2008 onwards; attitudes of midwives towards risk management; clinical governance in maternity care, English language and within the UK and other countries, except the US (as obstetricians are the lead professionals in childbirth). The time period chosen was aimed at capturing data from the commencement of well-known national drivers surrounding risk management in the NHS (Fenn and Egan, 2012).

Exclusion criteria

Excluded studies comprise; risk assessments for determining risk category in pregnant women, men, obstetric emergencies, student midwives, obstetricians, studies predating January 2008, and the US (as obstetricians are the lead professionals in childbirth).

Data synthesis

The literature was reviewed using a thematic approach of nine relevant papers (Table 1), highlighting the three major themes (right). This approach combined the relevant qualitative research, identifying key phrases and ideas and, finally, highlighting consistencies and differences between the studies. Whilst this is a critical literature review, some tools from systematic review were used to organise the findings.

| Author and country | Aim | Methods | Sample/participants | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Allen et al, 2010

|

Examining the safety culture in one maternity service, and how the use of surveys and interviews help bring an understanding to improve safety | Interviews, questionnaires, surveys, case study and review of key policies | 59 responses out of 210 midwives (28%); one maternity service across two public hospitals; 15 semi-structured interviews | There was insufficient infrastructure to support incident management activities to improve safety |

|

Skinner, 2011

|

To examine how midwives referred women to obstetricians, exploring their experience of the referral guidelines | Questionnaire (survey) to midwives and focus groups | 311 out of 649 midwives responded to the questionnaire and 32 midwives participated in 6 focus groups | Despite midwives identifying risk factors which fit the criteria for referral to an obstetrician, midwives had a strong desire to be with women; focussing both on normality and risk |

|

Scamell, 2011

|

To examine how midwives make sense of risk and requirements, whilst being with pregnant women | Qualitative-ethnographic study, interviews, observations and textual analysis | 42 participants and 15 non-participants observation of key meetings, 27 ethnographic interviews and textual analysis (four midwifery settings) | The manner in which midwives practised introduced doubt, searching for and magnifying risk resulting in a disturbance of the normality paradigm |

|

Scamell and Alaszewski, 2012

|

To examine how risk is categorised in childbirth, and how categorisation can shape the decisionmaking process in the management of risk in childbirth | Ethnographic studyqualitative, observation and recording midwifery talk and practice, in a number of clinical areas | 42 participants and 15 non-participants observation of key meetings, 27 ethnographic interviews and textual analysis (four midwifery settings) | Categorisation of risk shapes and is shaped by the social context of decision-making; all births being classified as ‘risky’, enticing midwives to comply with the riskadverse culture to constantly undertake surveillance |

|

Scamell and Stewart, 2014

|

To examine the impact of clinical governance on midwifery practice | Ethnographic studiesqualitative. Two conducted case studies examining midwives' talk and practice as pertaining to risk | Study 1: 20 women 10 midwives participated |

Midwives in the studies used both adherence to risk technology and flouting it as a means of asserting their professional identity and autonomy. The constraints experienced drove midwives to indulge in covert practices, such as ‘quickies’ (vaginal examinations) |

|

Simms et al, 2014

|

To conduct an exploration into the experiences and opinions of staff directly involved in risk management | Qualitative-ethnographic study. Collection of data from maternity databases, semistructured interviews | 27 staff from 12 out of 15 maternity units (obstetric and midwifery risk leads) | Staff were concerned about the accuracy and validity of local data, amidst scepticism surrounding demands from national benchmarking schemes; concerns over the impact of the local culture in maternity services on the degree of engagement with risk management |

|

Scamell, 2016

|

To investigate how intrapartum midwives choose the methods to gain knowledge on risk and how their choice of methods informed their clinical practice | Qualitative-ethnographic study, observations, interviews, analysing of texts, policy documents, meeting minutes and staff memoranda | Participants include 33 midwives, 1 student midwife, 5 obstetricians and 19 service users | The focus was to establish the inherent risks in pregnancy and childbirth; secondly, on organisational risks. The blurring of these lines through midwifery talk and practice invites uncertainty and amplification of risks by midwifecultural influence |

|

Skinner and Maude, 2016

|

To explore the how the concept of risk is placed in midwifery practice | Qualitative-ethnographic study. Postal survey and 6 focus groups | 52% of 649 midwives (337) participated in the postal survey | Midwives were challenged by the dichotomy of normal childbirth and being with women against working with complexities which introduced uncertainty |

|

Akbari et al, 2017

|

To assess safety attitudes in the maternity care units of public hospitals in a region of high maternal death rate | Qualitative-ethnographic study. Cross-sectional survey and questionnaire | 364 staff participated (314 were midwives) | 62% of staff agreed that safety in the ward and hospital was acceptable, but safety was graded significantly lower among midwives. Iranian maternity care system mainly focussed on a risk culture approach rather than a safety culture |

Findings

A total of nine studies were identified reporting the results of six studies. All the studies were qualitative and a variety of methodologies were used; identified in Table 1. Study participants were midwives from four different countries (UK, New Zealand, Iran and Australia) who worked in variety maternity settings including community, low- and high-risk units.

Thematic analysis

Three key themes were identified: midwives ‘being with women’; midwives and normality, and increased sensitivity to risk; and organisational risk technologies and blame.

Theme 1: midwives ‘being with women’

Four of the nine studies identified common themes relating to midwives on normality and ‘being with women’, and increased sensitivity to risk (Scamell, 2011; Skinner, 2011; Scamell and Alaszewski, 2012; Skinner and Maude, 2016). In the studies, the methods used were similar by way of surveys, questionnaires and interviews.

The sample used in the above four studies were representative of varied maternity settings, although the same participants were used in Skinner (2011), Scamell and Alaszewski (2012), Skinner and Maude (2016), and Scamell (2016). Entrenched within the concept of midwives ‘being with women’ is a well-known basic social construct as the identity of a midwife as highlighted in a paper by the International Confederation of Midwives ([ICM], 2011). In essence, the leadership position of care in childbirth rests with the midwife (Midwifery 2020, 2010). ‘Being with women’ means that midwives are the lead professionals for care in pregnancy and childbirth. This was evident throughout the four studies, covering maternity units across Iran, Australia, New Zealand and the UK.

The studies (Skinner, 2011; Skinner and Maude, 2016) highlighted that midwifery as a profession carries the inherent notion of midwives caring for women (ICM, 2011) in a low-risk and normal environment. In Skinner (2011), midwives were seen to be embracing their roles as leaders of normality with a strong desire to be with women in a professional relationship. This was irrespective of the level of risk identified in the woman and transfer to consultant care; akin to being the carrier of the risk to protect women.

The study revealed that out of the 1477 women who were referred for consultation at any time, the consultant was the lead professional in 608 women. However, of the 608 women, 415 continued to receive midwifery care. Whilst taking the appropriate actions through referral to an obstetrician once risks were identified, midwives continued to execute the midwifery component of care. Midwives viewed the woman's needs to be at the core of midwifery practice in which sits relationship and trust.

Theme 2: midwives and normality, and increased sensitivity to risk

The Scamell (2011), and Scamell and Alaszewski (2012) studies revealed threats to normality and constant risk assumption and surveillance. In the Scamell (2011) study, it was highlighted that midwifery and normality were uniquely linked, and in 66% of births, midwives were the senior leaders. However, doubt emerged in midwives' practice, owing to an element of pressure to be ‘risk aware’, leading to the constant searching for and amplifying of risks; thus disturbing the ‘normality’ paradigm.

The studies demonstrate that the normality discourse is threatened, owing to the increased preoccupation with risk and surveillance. Further, the preoccupation with and increased sensitivity to risk determined the model of care. The study rightly exposed that risk in birth has become a key focus and the drivers for such medicalisation of birth are borne from a national standpoint (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014).

In the Skinner and Maude (2016) study, 337 out of 649 midwives participated and expressed an appreciation for the importance of being accountable practitioners, but anxiety was caused by the medico-legal aspect of clinical midwifery and the negative impact of the risk environment on the ‘being with women‘ paradigm. In the above study, midwives were challenged by the dichotomy of normal childbirth and being with women, versus working with complexities which introduced uncertainty. Midwives saw women with risk quite capable of achieving normal births; however, the social model of birth was threatened by increased interventions and risk dominance. This then increased the likelihood of uncertainty and a false hope of control.

The mixed method approach (survey and postal questionnaire) used by Skinner (2011) attracted 311 out of 649 midwifery participants. The findings highlighted that there is a threat to the normality paradigm, as midwives through their talk and practice searched for and magnified risks. This study also revealed that the risk management concept enmeshed within clinical governance has served to challenge and threaten midwives' position within that social construct, and thereby reshaping the equilibrium between normality and risk surveillance.

The study by Scamell and Alaszewski (2012) used the same participants as Scamell (2011), and both engaged largely in content analysis of the data. Both studies focused on risk categorisation. They found that midwives are conditioned by virtue of adopting risk classifications in childbirth to comply with the risk culture, which sits outside the normality discourse and the blame flowing from adverse outcomes instils fear in midwives (Page and Mander, 2014). In both studies, midwives feel obligated to focus on monitoring and using tools, especially in labour to provide a trajectory; a focus on small chances of things going wrong.

Theme 3: organisational risk technologies and blame

The Scammel and Stewart (2014), and Scamell (2016) studies reveal that organisational risk technologies dominated and dictated midwives' talk and practice. The findings demonstrate that midwives feel that their ‘normality’ role is fading away and there is a growing culture of risk, fear and blame apportioning; therefore, increasing uncertainty (Scamell, 2016). Additionally, the growing assumption of abnormality exists and has catapulted into the resultant prioritisation of risk technologies. Midwives were seen to be flouting national guidance on vaginal examinations to assert their professional identity, as there is pressure to conform (Scamell and Stewart, 2014). In essence, the study showed that some midwives avoided documenting the true findings of vaginal examinations, especially where there was a potential to trigger medical interventions. Although midwives embraced evidence-based approaches, they viewed prescribed pathways as potential for disaster. They focussed on minimising risk for women and exercising their professional judgement and intuition as a form of self-regulation.

Scamell (2016) highlighted a critical point about the imbalance of two models coexisting in clinical midwifery. The study showed that the culture of midwifery is leaning towards a reversal of direction; the priority being organisational risk technologies with the normality agenda occupying a secondary position. The findings made it clear that the object focus was categorisation of risk and organisational risk technologies. Additionally, midwifery care finds itself sandwiched between variants of past incidents and unforeseen risks; embedded within a cultural discourse. This study draws on similarities on this area in others (Akbari et al, 2017).

The difference between the Scamell studies and Akbari et al (2017) is that in the former, there were less participants (33 midwives) as opposed to 314 midwives in the latter. Although both studies were focussed on the intrapartum clinical setting, Akbari et al's study was specifically addressing midwifery units with high maternal death rates. The other difference in the two studies is that Akbari et al (2017) included the entire service as opposed to Scamell who focused only on intrapartum care.

Nonetheless, both studies found that improving safety has been met with behaviour emanating from culture (Akbari et al, 2017). This is a common finding that risk management principles are fixated on risk culture rather than safety. Culture was cited in (Scamell, 2016) and the emphasis was placed on midwives not having sufficient time for engagement, and highlighted that risk must be viewed in a social and cultural context.

As highlighted in the Allen et al (2010) study, safety culture played a significant role and sought to expose some contributing factors for the disconnect between risk management principles and actual practice. Similarities in data can be seen in the studies (Simms, 2011; Scamell and Stewart, 2014; Scamell, 2016; Akbari et al, 2017) which draw on much broader theories and concepts; enveloped within culture, including risk technology and other contributing factors. More than one study refers to the safety culture in maternity units (Allen et al, 2010; Scamell, 2016; Akbari et al, 2017).

Study critique

The response rates were appropriate for the aim of the studies, especially as the participants were largely clinical midwives with significant experience of the growing culture to integrate risk management into midwifery practice. Scamell and Stewart (2014) used the case study approach. It is unclear whether the authors fully engaged with Yin's strict or Stake's more flexible approach to case studies (Yazan, 2015), therefore opening the floodgates to postulation on the validity and reliability of the findings. Equally, the finding made regarding the link between midwives' practice on managing vaginal examinations and risk also has the potential to adversely impact on validity and reliability, as the figure does not represent a large number of midwives.

In Simms et al (2014), the methods used for gathering the data (interviews and databases) were appropriate in seeking to achieve the aim of the study. The approach used to achieve full accuracy during analysis of the data was sufficiently detailed in this study. The methodology used in the Scamell (2016) study embraced the different settings where intrapartum care was focused on a hypothesis to be tested; that risk in midwifery practice and talk need a thorough investigation. The settings and design were commensurate with the aim of the study. However, the study failed to identify the root cause/key factors for midwives' inability to participate in the risk agenda such as audit; to improve the culture. Considering the author highlighted the dearth of information on risk management experiences, it failed to undertake a thorough analysis on factors affecting midwives.

Whilst less midwives responded positively to the question of whether the grade of safety in the ward and hospital were acceptable in the Akbari et al (2017) study, it lacked depth as to the questions asked of midwives, because it did not focus on factors affecting implementation of risk management principles and those impacting on safety.

The other study (Allen et al, 2010) demonstrated some flaws which includes reflection of the safety culture at one point in time, poor local engagement and the single method used to measure safety; rendering the findings unreliable. While the study used a small sample of participants with overlapping themes, it was well written in line with its aim. The Skinner (2011) paper erroneously states this is a 56.5% response rate, rather than 48%; leading to questions about the findings.

Overall, whilst the studies highlight some important points, there were a number of limitations of this review, which include the same authors (Scamell and Skinner) in more than two studies and little primary research was found outside of electronic databases.

Discussion

The findings establish that there are two main competing discourses in the world of midwifery; that of normality and risk management/surveillance. The studies identified that the midwives were not fully comfortable with the concept of risk management, mainly because it conflicted with practice and further, there was an element of disempowerment as a consequence.

Whilst the studies sought to unearth the impact of risk on clinical midwifery aligned to safety culture, they failed to explore key factors pertaining to risk management, directly impacting on the social reality of midwifery practice. The study on midwives' attitude to vaginal examination based on fear of medical intervention which is associated with risk (Scamell and Stewart, 2014), exposed an area of midwifery practice which is significant in determining progress in labour.

Some of the studies referred to risk categorisation as part of the entrenched risk management framework for pregnant women, but have not addressed how the other key principles within that construct fit with midwives' practice in reality. Jordan and Murphy (2009) suggest that risk assessments are important to assist with outcomes, but there is a need to find the balance. It would have been beneficial if the studies had taken an approach whereby, the midwifery participants were enabled to demonstrate their understanding of the salient features of risk management as pertaining to midwifery and the direct connection and responses to it in practice.

Further research is needed to explore and uncover the question; do risk management principles fit with the social reality of midwives ‘being with women’? My research will seek to uncover the factors affecting midwives' ability to make a genuine connection with risk management principles, and working safely and competently within their inherent social construct as independent practitioners.

Conclusion

The literature review reveals the absence of primary research on how the risk management principles and framework match the social reality of clinical midwifery in all settings. The literature has, to a larger extent, touched on some factors which fall under the risk umbrella with regards to safety and culture. Nonetheless, there is little depth regarding how the risk expectations can be safely combined with clinical practice, to achieve a satisfactory equilibrium between risk surveillance and normality.