The loss of a baby is an overwhelming experience for parents and families (Serrano et al, 2018). Approximately one in five parents suffer intense and prolonged grief following the death of a baby at the time of birth (Meaney et al, 2017). The death of a baby through miscarriage, stillbirth, neonatal loss or elective termination for fetal abnormalities is an experience with devastating impacts, affecting more than 5 million women globally (de Andrade Alvarenga et al, 2021). Globally, 20–30% of pregnancies result in miscarriage (Meaney et al, 2017), and in 2021, the global stillbirth rate was 23.0 per 1000 births at 20 weeks' gestation or later (Comfort et al, 2023). In 2021, more than 5000 babies per day were stillborn at 28 weeks or more, accounting for approximately 1.9 million stillbirths (Unicef, 2023).

Definitions of pregnancy loss vary. The World Health Organization (2021) defines perinatal loss as fetal death from 28 weeks onwards, and infant deaths up to the seventh day postpartum. Others define perinatal death as including pregnancy loss from early miscarriage (up to 12 weeks), late miscarriage (13–23 weeks), and stillbirth (intrauterine death after 24 weeks) (Hughes and Riches, 2003). Some researchers extend this period to include birth and up to 28 days after birth (Cassidy, 2018; Berry et al, 2021). Pregnancy loss includes all types of loss, including spontaneous and medically supervised terminations that can occur during a pregnancy from the first to third trimester (Health and Safety Executive, 2022).

The death of a fetus can cause parents great suffering from the loss of their dreams of a future life with the baby (Due et al, 2017). Parents and families must receive adequate support from carers and their direct social network to manage their grief (Koopmans et al, 2013). Although both parents experience painful grief following a perinatal loss, reactions to grief may vary according to gender (Arach et al, 2022). For mothers, pregnancy and childbirth are usually joyful transitions. Perinatal loss disrupts this process, and can alter maternal self‑perception, causing considerable psychological and physical stress (Kirui and Lister, 2021).

Over the past 30 years, a substantial body of research has examined the psychosocial impact of perinatal loss on mothers (Sutan et al, 2010). In addition, primary research on pregnancy and perinatal loss has significantly increased in recent decades, with much of this work focusing on quantifying the prevalence of gestational loss and exploring its underlying causes (Badenhorst et al, 2006; Ugwumadu, 2015). Other studies have explored mothers' experiences following perinatal loss, addressing factors such as the role of hope after perinatal death (de Andrade Alvarenga et al, 2021) and the specific bereavement support needs of women coping with such a loss (Fenstermacher and Hupcey, 2019). Qualitative review studies have analysed the phenomenon from the couple's or father's perspective. Berry et al (2021) conducted a metasynthesis on couples' experiences of perinatal loss and concluded that it is a transformative event leading to further kinds of loss and an intense and complex emotional response. Some studies have reported that fathers tend to express grief less intensely than mothers (Badenhorst et al, 2006; Turton et al, 2006). When looking at the phenomenon from the father's perspective alone, Aydin and Kabukcuoğlu (2020) found that, for social and cultural reasons, the father is seen as a more resilient figure and an emotional force who has a role in supporting and protecting the partner after the loss. Nevertheless, the authors demonstrated that the belief that a father's role is solely supportive in perinatal loss is inaccurate (Berry et al, 2021). A longitudinal study on bereavement in mothers and fathers who lost children to cancer revealed differences and changes in parental experiences over time, with mothers showing more intense grief reactions initially that gradually subside over time. In terms of coping strategies, mothers maintained closer contact with their extended family and focused more on their surviving children, while fathers concentrated mainly on work and practical activities (Alam et al, 2012).

To provide holistic, gender‑appropriate, and culturally sensitive care, understanding the values and needs of parents during perinatal loss is essential (Berry et al, 2021). In particular, focusing on maternal perceptions and experiences is key to improving care for women in this context. There is a significant gap in the systematic exploration of maternal perspectives on gestational loss. A review centred specifically on mothers' experiences could provide a valuable contribution to the field, offering deeper insights into this unique experience and its broader implications. The aim of this review was to examine pregnancy loss solely from the mother's perspective, systematising the findings.

Methods

This thematic synthesis of qualitative research was conducted to identify common themes and implications for practice (Thomas and Harden, 2008; Butler et al, 2016). This method allows for a deeper understanding of complex issues by synthesising diverse perspectives from existing qualitative studies.

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‑analyses model was used to organise and report the study selection and data extraction process (Moher et al, 2009). Tong et al's (2012) guidelines on enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research were followed, increasing the clarity, reliability and reproducibility of the review process. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO® under number CRD42023407314 and is publicly available (Moreira Freitas et al, 2024).

Search strategy

The research question was formulated using the population, context, and concept framework. Respective descriptors in English were identified using search syntaxes appropriate to each of the databases searched: Medline, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Scopus and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

The following keywords were used: perinatal loss, gestational death, perinatal death, gestational loss, stillbirth, fetal death and fetal loss, combined with mother, pregnant, parents, experience, attitude, perception, perspective and view. Combinations of descriptors, medical subject headings and subject terms were used for each of the databases through the Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’, used in search queries to refine and control results, making it easier to find relevant information. The search was conducted by the first author.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were primary qualitative studies involving women aged ≥18 years who experienced pregnancy loss before or during childbirth, focusing on their experiences and perceptions. The search was limited to studies published between 1 January 2012 and 31 March 2024 to ensure that the evidence included was as recent and relevant as possible. Studies involving voluntary or medical terminations, twin pregnancies and post‑birth infant deaths were excluded, as were those published in languages other than English, Spanish or Portuguese. The principal investigator is proficient in these three languages, ensuring accurate comprehension and analysis of the original texts without requiring external translation or validation. Studies were only considered for analysis if it was possible to determine that the results exclusively concerned the mother and death before or during birth.

Selection and quality assessment

Search results were imported into reference management software. Duplicates were removed, and two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full texts of the remaining references were reviewed for inclusion in the final review. Discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third researcher for consensus. The articles included were coded and numbered chronologically.

The studies were appraised for rigour, credibility and relevance using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program tool for qualitative research (Hannes, 2011). The tool is designed to help researchers evaluate the quality of qualitative studies based on criteria such as study design, clarity and potential for bias, making it easier for non‑specialists to assess methodological rigour.

Two reviewers independently applied the appraisal tool, resolving disagreements with a third reviewer. A scoring system was used to exclude studies with lower quality ratings; only studies scoring above 5 points were included in the synthesis. This threshold was chosen to ensure that only studies meeting a high standard of rigour contributed.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data were obtained using customised extraction forms, recording authorship, year, country, study objective, participant characteristics, data collection method, results and quality score (Hannes, 2011). Data extraction involved multiple independent readings of the articles.

Thematic synthesis was used to synthesise data (Thomas and Harden, 2008). A three‑step analysis was conducted as recommended (Barnett‑Page and Thomas, 2009). First, text segments from the results and discussion sections were independently coded line by line by two researchers using ATLAS.ti® (version 23), considering first‑order (participants' expressions) and second‑order constructs (authors' categorisation). Second, raw codes were labelled to form descriptive themes, which were discussed and finalised by consensus. Finally, analytical themes were generated inductively (Barnett-Page and Thomas, 2009) from the descriptive themes, with continuous comparison and relation of codes, using diagrams and mind maps to explain themes. The final analytical themes were presented as a main theme with several sub‑themes, illustrating their relationships, which built a visual structure.

Results

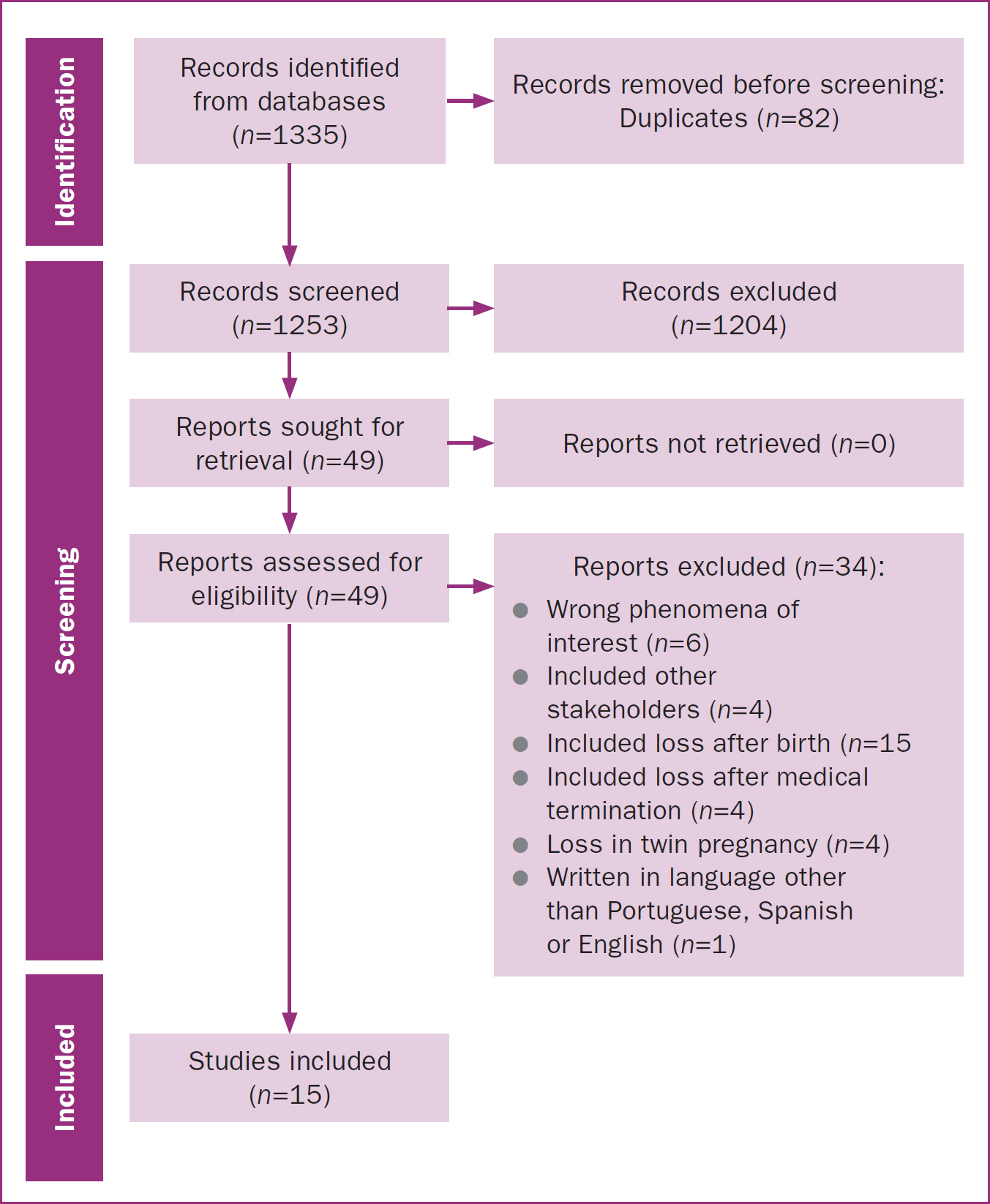

A total of 1335 articles were initially retrieved. After removing duplicates, 1253 articles were selected for first analysis by title and abstract. The 49 articles remaining after screening were read in full, with 15 included in the final review (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarises the included studies' characteristics. In cases where studies included mothers and other groups or examined fetal/neonatal death before, during and after birth, this review focused on findings specifically related to mothers and when death occurred before or during birth.

| Reference and setting | Aim | Participants | Methods | Main themes | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordlund et al (2012) Sweden | Explore experiences of mothers after death of a baby and interaction with healthcare professionals | Women (n=84) who lost a baby before/during labour, after 22 weeks and answered ‘yes’ to open question | Content analysis of open question ‘do you currently feel sad, hurt, or angry because of something health professionals did in relation to your baby's birth?’ | Sad, hurt or angry about something healthcare professionals did (or did not do) during birth | 7.0 |

| Murphy (2012) UK | Explore the parental stillbirth experience | Mothers (n=12) and couples (n=10; 5 had joint and follow-up interviews) | Qualitative, in-depth interviews, grounded theory analysis | Stillbirth as stigmatising, finding positive in loss | 7.5 |

| Golan et al (2016) Israel | Examine meaning that women attribute to loss and the lost figure | Women (n=10) who experienced a stillbirth | Qualitative based on phenomenology, in-depth interviews | Perception of lost figure, essence of stillbirth: prolonged internal ambiguity | 8.5 |

| Osman et al (2017) Somalia | Describe experiences of Somali Muslim mothers who lost babies at birth | Women (n=10) who lost babies before they were born | Qualitative based on Giorgi's phenomenology; semi-structured interviews | Alienation, altered stability, pain when sight of baby turns into precious memory, wave of despair eases | 8.5 |

| Gopichandran et al (2018) India | Understand psychosocial impact, aggravating factors, coping styles and health system's response to stillbirth | Women (n=8) who had stillbirth in last year; healthcare professionals (n=2) | Qualitative, in-depth interviews | Insensitive attitudes of healthcare providers, poor quality of health system and services, search for cause and blame, guilt and remorse, grief, factors aggravating grief and guilt, coping strategies | 9.5 |

| Nuzum et al (2018) Ireland | Explore lived experiences and personal impact of stillbirths on bereaved parents | Women (n=12) and men (n=5) from babies born after fetal death | Qualitative, in-depth semi-structured interviews, analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis | Maintaining hope, importance of personhood of baby, protective care, relationships (personal and professional) | 8.5 |

| Camacho-Ávila et al (2019) Spain | Describe and understand experiences and perceptions of parents who had a perinatal death | Women (n=13) and men (n=8) who had perinatal death | Qualitative based on Gadamer's hermeneutic phenomenology, in-depth interviews | Perceiving threat and anticipating baby's death, emotional outpouring, need to give identity to baby and legitimise grief | 9.0 |

| Martínez-Serrano et al (2019) Spain | Explore parents' experiences with care received during labour in cases of stillbirth | Women (n=7) and men (n=4) who have experienced a stillbirth | Qualitative with hermeneutic phenomenological framework, semi-structured interviews | Denial of grief, life and death paradox, guilt, go through and overcome loss | 9.0 |

| Ahmed et al (2020) Pakistan | Explore cultural practices in pregnancy and childbirth and perceptions of women with recent perinatal deaths | Women (n=25): 11 stillbirths and 14 early neonatal deaths | Qualitative exploratory, in-depth interviews | Perceptions and use of traditional home remedies, lack of emotional support and care, perceived causes | 6.5 |

| Fernández-Sola et al (2020) Spain | Explore, describe and understand impact of perinatal death on parents | Women (n=13) and men (n=8) who had perinatal death | Qualitative based on Gadamer's hermeneutic phenomenology, in-depth interviews | Perinatal death affects family dynamics, parents' social environment severely affected | 9.0 |

| Sinaga et al (2020) Indonesia | Explore experiences of mothers with intrauterine fetal death/miscarriage | Women (n=7) who experienced intrauterine fetal death | Descriptive qualitative with phenomenological approach, in-depth interviews | Mothers' response: loss is painful and traumatic experience, moral support received, negative behaviou from others, physical and psychological changes that interfere with role as wife and mother | 7.0 |

| Asare et al (2022) Ghana | Explore parents' psychosocial experiences of child loss | Women (n=18) and men (n=2) who experienced prenatal, perinatal or postnatal loss | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | Emotional, psychological and social experiences, financial loss | 8.0 |

| Popoola et al (2022) Nigeria | Describe beliefs and strategies for coping with stillbirth | Women (n=20) who lost their baby antepartum or intrapartum | Qualitative, descriptive approach, phenomenography, semi-structured interviews and focus group with 7 women | Beliefs about stillbirth, strategies for coping | 9.0 |

| Amankwah et al (2023) Ghana | Explore lived experiences of mothers with perinatal loss | Women (n=9) who lost baby in womb after 28 weeks or in first 7 days after birth | Qualitative, exploratory-descriptive design and hermeneutic phenomenology, semi-structured interviews | Maternal experience of loss, maternal reaction to loss, poor communication and counselling | 8,5 |

| Popoola et al (2024) Nigeria | Describe women's experiences of bereavement after death of stillborn child | Women (n=20) who had stillbirth | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | Experience of care in health facilities, emotional and psychological experiences, coping with stillbirth” | 9,0 |

Six of the included studies were European (Murphy, 2012; Nordlund et al, 2012; Nuzum et al, 2018; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020), four were Asian (Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Ahmed et al, 2020; Sinaga et al, 2020), and five were African (Osman et al, 2017; Asare et al, 2022; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024; Amankwah et al, 2023). One had a mixed methodological approach (Nordlund et al, 2012), with the remaining studies being exclusively qualitative.

For data collection, almost all studies used semi-structured (Osman et al, 2017; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Asare et al, 2022; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024; Amankwah et al, 2023) or in-depth interviews (Murphy, 2012; Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Nuzum et al, 2018; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Ahmed et al, 2020; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020; Sinaga et al, 2020). All but two of these studies conducted individual interviews, while Murphy (2012) conducted joint interviews and Popoola et al (2022) used focus group methodology. The mixed study performed content analysis of an open question (Nordlund et al, 2012).

There was a large disparity between studies in terms of the time elapsed between the loss and the interviews. Some studies held interviews at a specific time point after the loss, including at 1–3 months (Osman et al, 2017), 6 months (Murphy, 2012; Sinaga et al, 2020) or 18 months (Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019). Others used wide timeframes, including between 3 months and 5 years (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020) or between 6 months and 3 years (Popoola et al, 2022; 2024). One study set a maximum time limit of 6 months (Amankwah et al, 2023), while two others set it at 1 year (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Ahmed et al, 2020). In one study, the time elapsed between the loss and the interview ranged from 1–9 years (Golan and Leichtentritt 2016). Three studies did not report the time elapsed between the loss and data collection (Nordlund et al, 2012; Nuzum et al, 2018; Asare et al, 2022).

In total, the studies involved 278 women who experienced a pregnancy loss. All studies explored spontaneous pregnancy loss/fetal death. However, in one study, 50% of the participants had received a diagnosis of a life-limiting condition (Nuzum et al, 2018). The studies considered fetal death occurring at different gestational ages, including from 22 weeks (Nordlund et al, 2012; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020), 23 weeks (Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016) 24 weeks (Murphy, 2012; Nuzum et al, 2018), 28 weeks (Osman et al, 2017; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024; Amankwah et al, 2023) and 32 weeks (Gopichandran et al, 2018). Two studies did not specify gestational age at the time of loss (Ahmed et al, 2020; Asare et al, 2022).

Methodological quality

Most of the included studies were of high quality, and generally fulfilled the criteria of the appraisal tool. The most critical aspect of this assessment was related to the relationship between the researcher and the participants, which was described in only two of the selected articles (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Popoola et al, 2024).

Themes

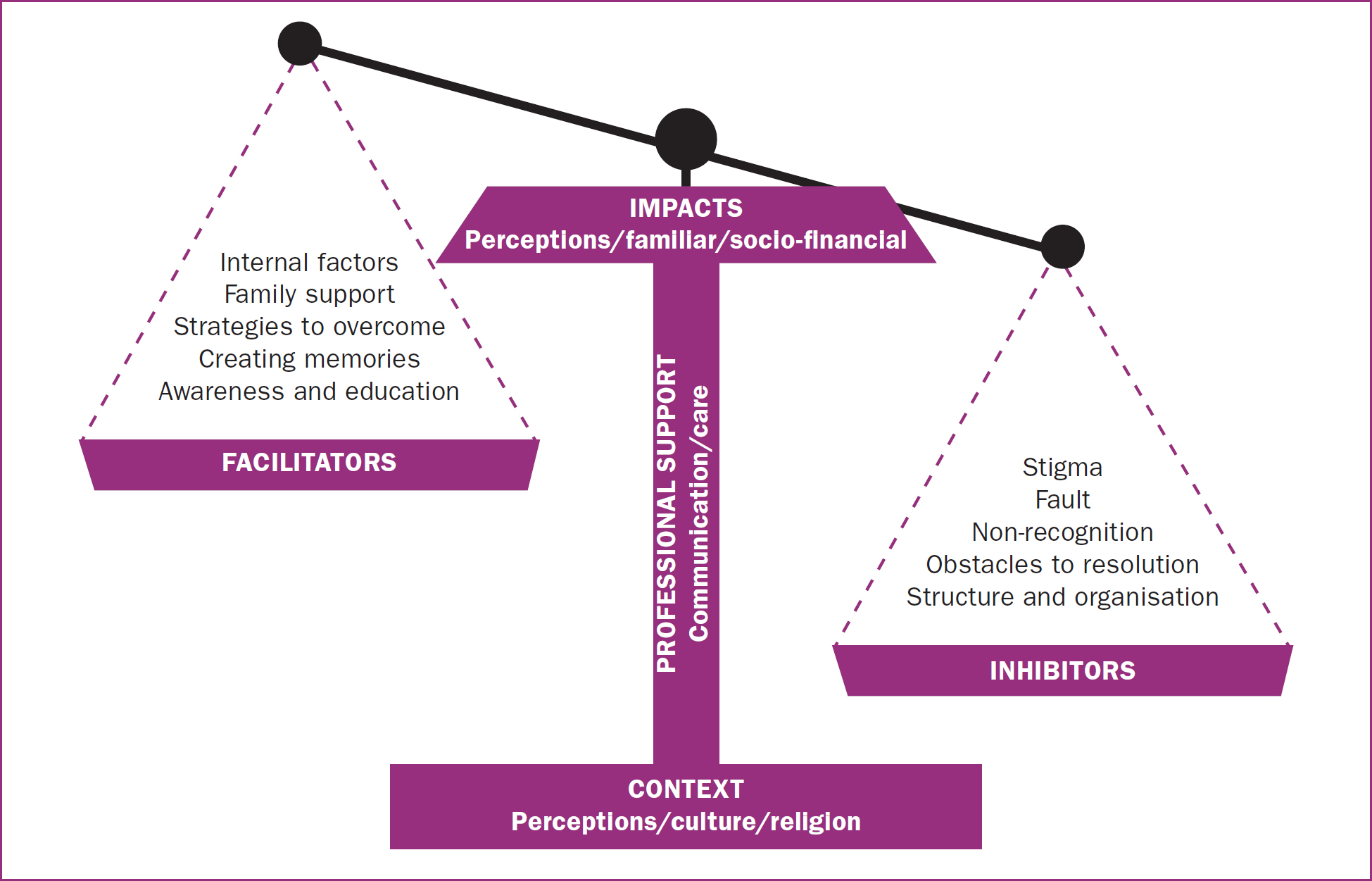

Five major themes were identified in relation to women's experiences of gestational loss: facilitators, inhibitors, contexts, professional support and impacts (Figure 2).

Facilitators

The studies reported on methods that mothers found helpful when managing pregnancy loss. This theme represented 35 quotes, including five sub-themes: internal factors, family support, strategies to overcome the loss, creating memories, and awareness and education.

The studies reported that mothers themselves recognised individual characteristics that facilitated coping and adaptation after the loss. Internal factors included attitudes of acceptance (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024) or feelings of gratitude for having survived the loss (Popoola et al, 2022).

Reported strategies to overcome the loss included focusing on looking after other young children (Gopichandran et al, 2018), or work (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020) as a way to keep busy and focused. Some reported having other children (Popoola et al, 2022) to manage their grief. Family, friends and neighbours were identified as important support elements (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Sinaga et al, 2020). Behaviours or attitudes, including seeing, touching and holding the baby (Osman et al, 2017; Nuzum et al, 2018; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Amankwah et al, 2023), helped mothers to experience the phenomenon, validating and recognising the existence of their child, and creating memories. Awareness and education addressed mothers' concerns about the experience of loss and their efforts to promote community awareness and education about pregnancy loss (Murphy, 2012).

Inhibitors

Several factors were reported to make the experience of loss difficult, representing a total of 60 quotes. Sub-themes in this area included stigma, fault, non-recognition, obstacles to resolution, and structure and organisation.

Behaviours that made the process harder included that the woman did not identify as a mother (Nordlund et al, 2012; Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Osman et al, 2017; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019) or did not recognise the fetus as a child (Nordlund et al, 2012; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019).

Fault and stigma were also identified as challenges to managing the loss. Women reportedly blamed themselves (Osman et al, 2017; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Nuzum et al, 2018; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Ahmed et al, 2020; Amankwah et al, 2023; Popoola et al, 2024) or healthcare professionals (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Ahmed et al, 2020; Asare et al, 2022). Stigma included reported behaviours of family members, friends and society that made the process harder, including social (Murphy, 2012; Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020; Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022) and family stigma (Murphy, 2012; Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Sinaga et al, 2020).

After the diagnosis of pregnancy loss, miscarriage or stillbirth, labour inevitably followed. Mothers highlighted that aspects of this process could be difficult, including experiences of physical pain (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019), fear (Osman et al, 2017), suffering (Osman et al, 2017) and regret, which was expressed by some mothers who did not see their dead baby (Nordlund et al, 2012; Osman et al, 2017).

Structural and organisational characteristics of health institutions were also identified as having a negative impact on the process. The lack of differentiated spaces for mothers during the loss often meant that mothers were exposed to seeing/hearing pregnant and postpartum women with living babies (Nordlund et al, 2012; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Nuzum et al, 2018; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Amankwah et al, 2023). Additionally, there were institutional policies that hindered the creation of memories (Nordlund et al, 2012; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Nuzum et al, 2018; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Amankwah et al, 2023). For example, there were restrictions on parents taking objects associated with their baby. Nordlund (2012) reported a mother's memory of initially not being allowed to take home the hospital blanket in which her baby had been placed, despite it being the only tangible item that carried his scent. She was only able to obtain it after experiencing severe anxiety upon returning home and agreeing to replace it with another blanket. Such policies can create additional distress for bereaved parents, making it more difficult for them to preserve meaningful memories of their baby.

Contexts

The theme ‘contexts’ included 59 quotes, grouped into three sub-themes that represented circumstances that significantly influenced the experience of pregnancy loss: maternal perceptions of the experience, culture (including customs, rituals and traditions that influence the experience) and religion, where beliefs and spirituality were addressed.

Several studies reported different women's interpretations of various aspects of the loss (Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Osman et al, 2017; Nuzum et al, 2018; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024; Amankwah et al, 2023). These perceptions were related to the lost figure, the perception/cause of death, and the mother's perception of the father's reaction.

Societal customs, practices, rituals and traditions shaping a mother's upbringing were also relevant, either facilitating or hindering recovery from the loss (Osman et al, 2017; Gopichandran et al, 2018; Popoola et al. 2022; 2024). Two studies highlighted that a mother's faith, spirituality, interpretation of dreams/nightmares and beliefs (for example, about omens or fate) were key in accepting and coping with pregnancy loss (Osman et al, 2017; Popoola et al, 2022).

Professional support

The theme professional support comprised 52 quotes, and identified healthcare professionals as key mediators. Professional support was seen as both a positive, facilitating factor by some women or a negative, hindering influence by others. Two main sub-themes emerged: communication and care. Mothers recognised a lack of communication (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Popoola et al, 2024) and inadequate information (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Asare et al, 2022) as hindering the grieving process. However, clear, honest communication from professionals, even when admitting uncertainty about the cause of the loss, was seen as helpful (Asare et al, 2022).

Mothers' testimonies highlighted the importance of how the diagnosis was communicated. Failing to prepare a mother for the news (Gopichandran et al, 2018) or waiting for a significant person to be present (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019) hindered the recovery process. In particular, managing silences and professionals' body language was seen as crucial (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019). Omitting the diagnosis was viewed as a barrier, although some mothers acknowledged that delaying the news sometimes allowed time to adjust without worsening their condition (Ahmed et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2024).

The subcategory care included healthcare professionals' behaviours and attitudes that facilitated or hindered the experience of loss. Mothers highlighted hindrances including poor professional practice (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Ahmed et al, 2020; Amankwah et al, 2023), preventing them from seeing/touching the baby (Osman et al, 2017; Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019; Popoola et al, 2024) and inappropriate behaviour (Nordlund et al, 2012; Gopichandran et al, 2018). Examples of poor practice included inappropriate interventions (pressure on the uterine fundus during expulsion, frequent vaginal exams, poor pain management, interventions without consent). Inappropriate/offensive behaviour included disrespect, verbal abuse, lack of empathy and accusations of inexperience/unreadiness.

Some mothers shared experiences and suggestions to improve care during pregnancy loss (Murphy, 2012; Nordlund et al, 2012; Golan and Leichtentritt, 2016; Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022). These prompts emphasised the need for compassionate, respectful and empathetic care to avoid unnecessary emotional suffering during a sensitive time. The importance of accurate and sensitive communication was emphasised, with one mother sharing her distressing experience of being congratulated for a birth while undergoing a procedure to remove the placenta after a loss (Nordlund et al, 2012). Another mother called for comprehensive support from healthcare systems, not only in the prevention of stillbirth but also in addressing broader issues related to reproductive health (Popoola et al, 2022). Mothers emphasised the importance of professional support in coping with pregnancy loss (Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Sinaga et al, 2020). Assertive, respectful care was key, helping mothers feel supported and respected, which was essential in navigating the loss.

Impacts

The theme ‘impacts’ outlined the consequences of gestational loss using 65 quotes, divided into three sub-themes that encompassed the personal, family and socio-financial dimensions of loss.

On a personal level, pregnancy loss led to a range of feelings, including frustration (Murphy, 2012; Popoola et al, 2022; Amankwah et al, 2023), shame (Murphy, 2012), feelings of unconsciousness, dizziness and tension (Sinaga et al, 2020), lack of concentration (Gopichandran et al, 2018), intense crying (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024), nervousness, insomnia, anger (Sinaga et al, 2020), sadness (Sinaga et al, 2020; Asare et al, 2022; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024), fear (Asare et al, 2022) and pain (Popoola et al, 2024). Immediate reactions such as shock (Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2024) and denial (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Nuzum et al, 2018) also reflected the impact of the loss.

The impact on future pregnancies included fear (Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Ahmed et al, 2020; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020), panic (Fernández-Sola et al, 2020), anxiety/distress (Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Popoola et al, 2024), trauma and pain (Sinaga et al, 2020), stemming from concerns about recurrence. However, future pregnancies also brought hope, and were seen as a potential way to overcome the loss (Gopichandran et al, 2018).

The family dimension subtheme covered the impact of pregnancy loss on marital relationships, other children and the extended family. In marital relationships, the loss led to estrangement and arguments with a woman's partner (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020). However, for some mothers, the experience brought the couple closer (Nuzum et al, 2018; Popoola et al, 2024). The loss also affected other children (Osman et al, 2017; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020), as well as the mother–child relationship (Fernández-Sola et al, 2020). Mothers noted that existing children suffered from the loss and expressed feelings of neglect (Osman et al, 2017; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020). To mitigate these issues, women used strategies such as omitting details to protect their children from additional suffering (Fernández-Sola et al, 2020) and increasing care out of a fear of losing their other children (Osman et al, 2017).

The phenomenon also affected mothers' social and professional/financial lives. Socially, mothers felt isolated and withdrew from friends during festive events such as birthdays and Christmas, as a result of grief (Gopichandran et al, 2018, Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020; Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024). The social impact was significant when interacting with pregnant women and children (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Martínez-Serrano et al, 2019; Sinaga et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022), which was especially challenging for mothers who had experienced pregnancy loss. On a professional/financial level, the loss led to significant expenses and difficulties such as depression and absenteeism (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Fernández-Sola et al, 2020), which sometimes resulted in job loss (Fernández-Sola et al, 2020).

Discussion

The death of a child during pregnancy or birth is a traumatic, complex and overwhelming experience that turns a typically joyful transition into a painful one (Ravaldi et al, 2018; Serrano et al, 2018; Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020; Berry et al, 2021). The loss can have significant impacts on parents and family (Due et al, 2017; Aydin and Kabukcuoğlu, 2020), with unfulfilled maternal desires causing severe pain (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão 2020). The impact of pregnancy loss varies based on personal, cultural and religious factors, as well as the support received from family, friends and healthcare professionals.

Pregnancy loss can have profound effects on women's personal, family and professional lives. Women may experience intense emotions, including anger, sadness, frustration, shame and tension. Parents can experience psychological trauma and shock, coupled with feelings of hopelessness and inadequacy; some may have nightmares as a result of perinatal loss (Aydin and Kabukcuoğlu, 2020). Normal responses to bereavement include depression, irritability, anxiety and changes in eating and sleeping (Koopmans et al, 2013). Depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder may persist in the longer term (Lisy et al, 2016).

This review's findings highlighted that pregnancy loss can affect future pregnancies, heightening fear and anxiety. In subsequent pregnancies, women may experience increased anxiety, depression and reduced prenatal attachment, with higher risks of complications and fetal death (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020). Recognising and managing anxiety in women with previous pregnancy loss is therefore crucial (Ugwumadu, 2015). Conversely, for some women, a new pregnancy can offer hope, easing grief despite the associated fears (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2019). Pregnancy loss also impacts other children, altering the mother–child relationship. Increased care for existing children, driven by fear of further loss, is common (Camacho-Ávila et al, 2020), although attention can also decrease (Aydin and Kabukcuoğlu, 2020).

Support from family and friends is vital when experiencing perinatal loss (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020). However, mothers may face stigma or insensitivity in their social circles (Berry et al, 2021). Professional support is therefore essential, and interactions with healthcare professionals can significantly impact parents, with lasting effects (Lisy et al, 2016; Berry et al, 2021). The quality of care provided during diagnosis, birth, post-birth and follow-up shapes experiences of pregnancy loss (Lisy et al, 2016). Effective communication during stillbirth/labour, respect for pain perception and comprehensive discharge preparation are essential (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020; Wheeler et al, 2022). Multidisciplinary support should be assertive, respectful and woman-centred to mitigate long-term psychological effects (Cacciatore, 2010).

Comprehensive care from healthcare professionals, especially nurses and midwives, can help mothers form a connection with their deceased baby, transforming grief (Cacciatore, 2010). Although grief is universal, its expression and coping strategies are influenced by social and cultural contexts (Fernández-Basanta et al, 2020). Reactions and coping mechanisms vary by culture, socioeconomic status, religion, ethnicity and personal characteristics (Cacciatore, 2010; Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020; Fernández-Basanta et al, 2020). This review highlighted significant cultural influences, with four of the included studies conducted in Asia, five in Africa and six in Western countries. The role of rituals, customs, and traditions was highlighted in the non-European studies (Gopichandran et al, 2018; Ahmed et al, 2020; Popoola et al, 2022; 2024). These findings underscore the need for culturally and spiritually sensitive care, respecting parents' beliefs, customs, and values (Alvarenga et al, 2021).

Support during perinatal loss should respect families' cultural backgrounds and preferences, including allowing parents to see the baby, take photos and arrange a funeral (Fernández-Basanta et al, 2020). Transcultural care is essential, informed by parents' cultural and historical contexts (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah, 2018). In low- and middle-income African countries, which have the highest stillbirth rates, cultural and religious factors are key to experiences of perinatal loss (Ugwumadu, 2015). Osman et al (2017) found that in Somalia, acceptance of death as Allah's will provided comfort. In Muslim culture, stillborn children are taken away immediately, and mothers typically do not see or touch them (Alvarenga et al, 2021). However, some women still wish to see and touch their babies, echoing findings from European studies (Nuzum et al, 2018), which stress the importance of sensitive care, including allowing mothers to see or touch their deceased babies and obtaining consent for interventions. Several of the reviewed studies emphasised the role of beliefs and spirituality (Osman et al, 2017; Popoola et al, 2022). Religion can help mothers cope with grief and find meaning in their loss, offering protection (Fernández-Basanta et al, 2020).

Implications for practice

While prior studies have explored the perspectives of couples (Berry et al, 2021) and fathers (Aydin and Kabukcuoğlu, 2020), and an increasing number address maternal experiences, the unique viewpoint of mothers in gestational loss remains insufficiently systematised. Unlike recent reviews focused on high-burden contexts (Kuforiji et al, 2023), this review encompassed both high- and low-income settings, providing a comprehensive view of the maternal experience across the entire trajectory of loss, from diagnosis to resolution. The findings underscore key facilitators and barriers to the recovery process, emphasising the role of communication, professional support and the influence of cultural and religious factors, as well as the broader personal, familial, and socioeconomic dimensions of loss from mothers' perspectives.

The findings of the review can be used to reformulate current hospital care and support systems for mothers who experience pregnancy loss. For example, spirituality plays a crucial role in adaptation, with stillbirth being one of the most challenging bereavements, causing lasting psychological, social, and financial impacts (Alvarenga et al, 2021). Promoting culturally and spiritually sensitive care is essential, and needs to address parents' beliefs, customs and values.

Healthcare professionals can support bereaved parents by anticipating their needs and offering high-quality, individualised care (Berry et al, 2021). Effective delivery of the initial diagnosis requires a considerate approach, using an appropriate tone and language for an individual mother's cognitive and socio-economic level (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020). Verbalising care availability is also crucial (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020). An evidence-based, woman-centred approach, free from personal biases, is essential (Fernández-Basanta et al, 2020). Nurses and midwives play a key role in compassionate care, from admission and diagnosis to childbirth and confronting loss (Casalta-Miranda and Brites-Zangão, 2020). Their care is crucial for psychological support (Wheeler et al, 2022) and a multidisciplinary approach should be ensured (Fernández-Basanta et al, 2020).

Limitations

This review synthesised and interpreted mothers' experiences based on 15 studies in which various experiences of perinatal loss were explored. Important information may have been unintentionally omitted because of the search strategy, for example because studies where the timing of death was unclear were excluded, and the results presented are limited to quotes from the selected qualitative studies. The diverse life experiences of participants, including those with miscarriage or infertility, may have influenced the results. Additionally, only studies published in English, Portuguese or Spanish were included. Although including multilingual studies adds diversity, nuances may have been lost in translation, especially regarding cultural or linguistic subtleties. The authors aimed to minimise this through a careful review process, but acknowledge that some meaning may have been impacted.

Conclusions

Maternal perception of pregnancy loss are deeply shaped by internal factors, cultural and religious aspects, and the support received from family, friends and healthcare professionals. This review's findings underscore the importance of recognising fixed factors, such as cultural and religious aspects, in providing sensitive care. Importantly, the review highlights facilitators and inhibitors that healthcare professionals can actively address to better support mothers experiencing loss.

Healthcare professionals play a central role as mediators, enhancing positive coping mechanisms and proactively addressing potential challenges. This requires an evidence-based, individualised approach, attuned to each woman's unique needs and wishes, free from imposed values and beliefs. To achieve this, professional training is needed to equip professionals with the necessary skills to support women compassionately and effectively through this experience. Midwives and nurses occupy a privileged position in offering compassionate care, fostering hope and guiding women through healthier processing of gestational loss.