Hyperemesis gravidarum is an important and under-recognised condition that can be debilitating for women. In 2021, an international Delphi survey created the Windsor definition for hyperemesis gravidarum, with the following criteria for diagnosis: pregnancy, intractable nausea and vomiting, with onset before 16 weeks' gestation, inability to eat and drink normally and significant impact on daily living (Jansen et al, 2021). Assessment tools for hyperemesis gravidarum include the pregnancy-unique quantification of emesis and nausea score to measure symptom severity. Quantification of nausea, vomiting, and retching symptoms are assessed indicating mild, moderate or severe impact (Hada et al, 2021).

While relatively rare, hyperemesis gravidarum has a reported incidence of 1.3% and is a leading cause of hospital admission for pregnant women in the first trimester of pregnancy (Nurmi et al, 2022). In addition to the physical maternal morbidity that can result in electrolyte disturbance, dehydration, malnutrition and weight loss, hyperemesis gravidarum symptoms can also cause a major psychosocial burden that may lead to depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and pregnancy termination (Boelig et al, 2018; Nana et al, 2021). Social isolation, loss of employment, inability to perform caregiving activities and relationship strain all contribute to poor mental health outcomes for women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum, emphasising the critical need for holistic assessment (Fletcher et al, 2015).

The aetiology of hyperemesis gravidarum has been poorly understood, and while research is evolving, beliefs around psychological causes persist (MacGibbon, 2020). The role of healthcare professionals' attitudes to women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum has been highlighted, with women describing doctors, nurses and midwives as disbelieving and unsympathetic, and that their concerns were trivialised (Gadsby et al, 2011; van Vliet et al, 2018). Poor healthcare experiences are unhelpful in improving women's mental health outcomes or optimising health outcomes for mother and baby.

Hyperemesis gravidarum clinical management lacks uniformity on a global level (Wang and Ma, 2018; Tsakiridis et al, 2019). Treatment centres on a combination of anti-emetic medication, fluid resuscitation with electrolyte replacement, nutrition support and lifestyle modification. Holistic assessment and support should be provided to address the psychological burden women experience, although research indicates this is often poorly executed (Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017a).

Assessment and treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum is frequently sought in the emergency department (Clark et al, 2024), and wide treatment variability and drug monotherapy are hallmarks of care (Sharp et al, 2016). Presentations for hyperemesis gravidarum increased between 2006 and 2014 in the USA, accounting for over 400 000 visits annually (Fejzo et al, 2023). Women accessing care through emergency departments experience long wait times and high rates of re-presentations for further hydration when their symptoms reoccur (Nurmi et al, 2022). Effective hyperemesis gravidarum management is complicated by a lack of clinician understanding of safety data to guide medication dosing in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding (Stock and Norman, 2019).

Out-of-hospital hyperemesis gravidarum management was proposed more than 30 years ago as a model of care that may be as cost effective as hospital-based management with comparable outcomes for women (Naef 3rd et al, 1995). Ambulatory or outpatient care models are services that provide acute medical care without inpatient admission or overnight stay and can include a ‘hospital in the home’ service (Lasserson et al, 2018). A systematic review into management options for hyperemesis gravidarum only identified two outpatient studies and concluded that day-case (outpatient) management of women with moderate to severe symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum was feasible and acceptable (O'Donnell et al, 2016). Outpatient models of care for hyperemesis gravidarum may have the potential to reduce hospital inpatient stays, leading to cost savings without negatively impacting women's care and outcomes.

Currently, there are no systematic reviews of the literature focusing on hospital outpatient models of care for women with hyperemesis gravidarum. This scoping review's aim was to identify and summarise the current literature regarding outpatient models of care available for women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum.

Methods

A scoping review was chosen as the most suitable methodology because it enables a wide-ranging sweep of available literature and evidence to highlight key aspects of hyperemesis gravidarum outpatient care, identify any gaps in the literature, and develop recommendations for future research (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005; Munn et al, 2022). To ensure a systematic process was followed, Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) scoping five-stage framework was used, requiring the researchers to identify the research question, identify relevant studies and papers, select the relevant papers for inclusion, chart the data and collate, summarise and report the results. The review question was formulated using the population, intervention, comparison, outcome model: for women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum, what are the characteristics and outcomes of the outpatient models of care currently reported in the literature?

Search strategy

A preliminary search of Medline (Ovid), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted in January 2023 and no current or underway systematic reviews or scoping reviews on the topic were identified. An initial scoping search was conducted in PubMed to identify a set of key relevant articles. The MeSH terms and keywords used to index these articles were used to create a search strategy.

MeSH terms and keywords were used separately and in combination with Boolean operators (OR, AND) to search Medline (Ovid). The search strategy was then adapted for Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), The Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. Searches were performed in January 2023 and updated in October 2024. Citation tracking, reference lists and Google Advanced searching were used to identify further references.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were decided before conducting the initial searches. All study methodologies and types of publication published in English between January 2010 and July 2023 were included. This timeframe was chosen to limit the review to contemporary studies, in order to reflect changes in hyperemesis gravidarum care globally. Studies and published reports, articles, conference papers and abstracts were eligible where the authors defined severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in a manner consistent with the characteristics of the Windsor definition and examined a care setting of an outpatient, community, ambulatory or home care model. The term ‘outpatient’ encompassed models of care provided in an outpatient, community or hospital in the home model, including day assessment units where women were provided intravenous fluid rehydration and/or medications during the day with no overnight care provision. Interventions were eligible if they offered a model of care appropriate for hyperemesis gravidarum that included aspects such as clinical review, medication administration and intravenous fluid resuscitation.

Studies were excluded if they did not meet the model of care outlined, the study design required hospital admission for inpatient treatment and management or the participants' diagnosis did not meet the Windsor definition of hyperemesis gravidarum. Studies were also excluded if the full text was not available.

Article selection

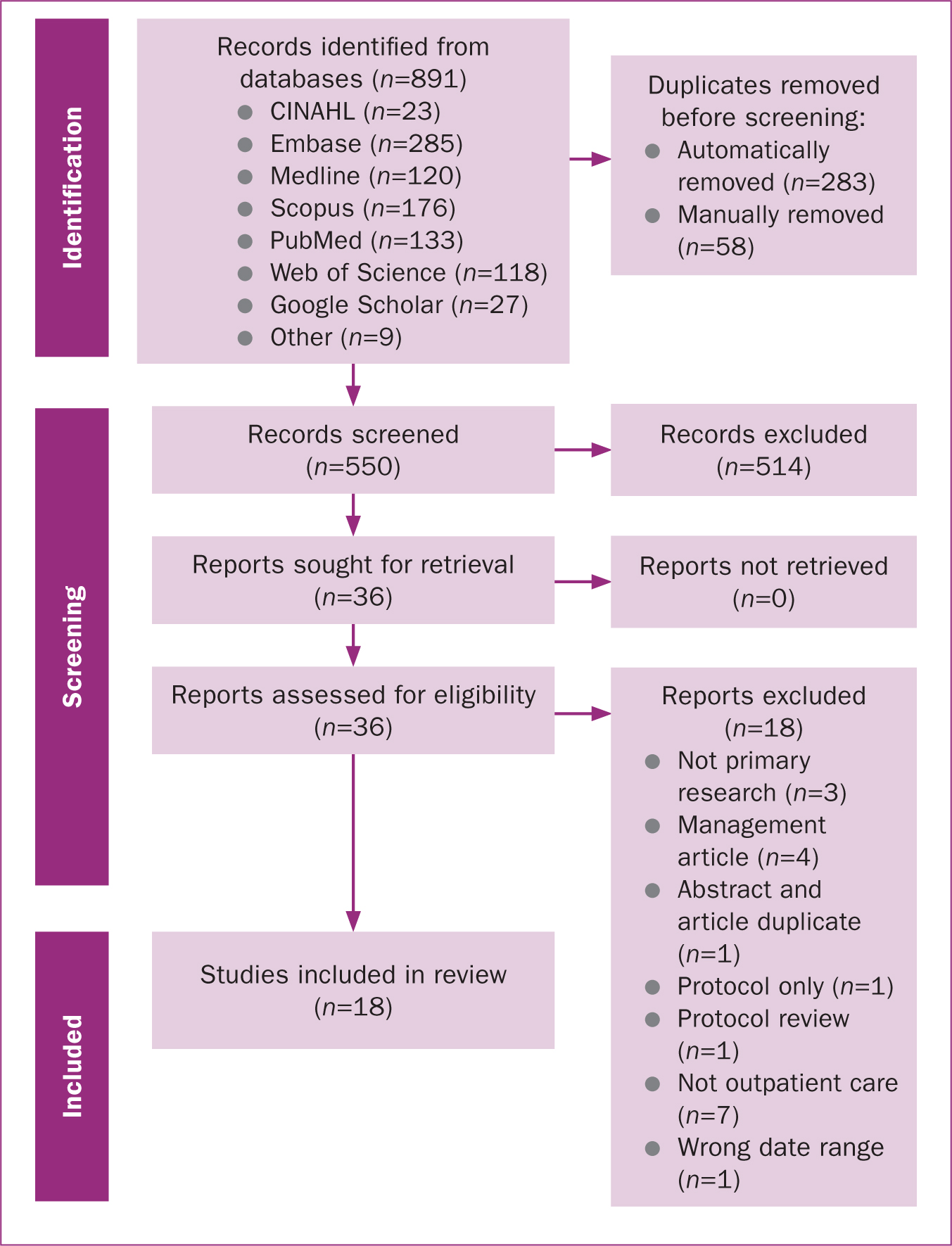

All eligible publications were exported into an EndNote library. Publications were then uploaded to the Covidence systematic review software and duplicates were removed. Retrieved references underwent title and abstract screening with the initial screening performed by two reviewers (RLP, PF) according to the eligibility criteria. Eligible articles were dual reviewed in full text with conflicts resolved by a third reviewer when required (KC). A PRISMA flow diagram detailing the selection process is shown in Figure 1.

A total of 891 citations were identified from database searches, with 341 duplicates removed, 283 identified following importation and 58 through manual searching. Following de-duplication, 550 records were eligible for title and abstract screening, with 36 records deemed eligible for full-text assessment. A total of 19 records met the inclusion criteria; however, an abstract and peer-reviewed paper reported the same data. The abstract was excluded, leaving 18 records for the final review.

Data extraction and analysis

The included studies were evaluated against the inclusion criteria by all authors using a data extraction template adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (Tricco et al, 2018). Data were categorised according to pre-defined fields arrived at via team consensus. Dual data extraction took place with discussion and resolution of disagreement or uncertainty through research team group consensus. Not all data fields were available in the published material. For all missing data, three attempts were made to contact the nominated corresponding author at the designated email for correspondence. Additionally, authors that could be located through research forums were contacted. Two replies were returned, and no additional data were obtained.

As a scoping review assesses the scope of available literature, quality assessment was not undertaken. A risk of bias assessment was not conducted because of the lack of data available. The included studies, literature and categorised outcomes are presented in a narrative summary because of the heterogeneity of the reported findings and the limited data identified.

Results

The 18 included studies' characteristics are summarised in Table 1. They consisted of full-text papers (n=10), and conference abstracts (n=8). The articles included qualitative studies (n=2), retrospective cohort studies/audits (n=4), case-control studies (n=2), randomised control trials (n=3), quality improvement projects (n=5), one economic evaluation and one survey.

| Reference and location | Aims | Design and dates | Conflicts of interest | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Channing and Doraiswamy (2021)

|

Quality improvement project introducing day case unit in gynaecology ward | Quality improvement Dec 2012–Oct 2018 | Not reported | None |

|

Coleman et al (2014)

|

Evaluate day case service | Audit |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Dean et al (2017a)

|

Identify reasons for women's preference of care settings | Qualitative part of cross-sectional survey |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Dean et al (2017b)

|

Establish if treatment in day case setting is associated with improved satisfaction compared to hospital admission | Survey |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Doherty et al (2023)

|

Ascertain women's experiences of hydration clinic, help assess viability and highlight improvements | Qualitative |

None declared | Health Services Executive Nursing and Midwifery Planning and Development Unit, South Dublin, Kildare & Wicklow |

|

Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy (2021)

|

Assess if patients are referred appropriately from GP and Accident and Emergency to gynaecology emergency care and onto ward, in line with national guidelines | Quality improvement |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Hordern et al (2013)

|

Determine admission rate, hydration status, length of stay and re-admission rates | Case control |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Ijaz et al (2016)

|

Analyse efficacy and performance of rapid hydration clinic | Audit |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Khan et al (2013)

|

Gain patient experience feedback, assess if protocol followed and hydration clinic successful in reducing inpatient admissions | Audit |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

McCarthy et al (2014)

|

Examine day care treatment compared with traditional inpatient management | Randomised controlled trial |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

McParlin et al (2016)

|

Assess feasibility of rapid intravenous rehydration and ongoing midwifery support compared to routine in-patient care | Randomised controlled trial |

Not reported | Funded by NHS Directorate of Women's Services, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University |

|

Mitchell-Jones et al (2017b)

|

Determine whether ambulatory outpatient treatment is as effective as inpatient care | Randomised controlled trial |

Not reported | Part-funded by National Institute for Health Research under Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care programme for Northwest London |

|

Murphy et al (2016)

|

Analysis of McCarthy et al (2014) |

Economic evaluation |

Not reported | Not reported |

|

Ostenfeld et al (2023)

|

Reorganise treatment offered to release midwife resources while optimising organisation and patient satisfaction | Quality improvement |

None declared | Part funded by Nordsjaellands Hospital as part of fellowship programme |

|

Ryan et al (2019)

|

Stratify patients into successful day case management | Case control |

None declared | Not reported |

|

Tompsett et al (2013)

|

Review implementation of structured ambulatory care bundle | Implementation plan/quality improvement |

Not recorded | Not recorded |

|

Ucyigit (2020)

|

Investigate impact of ambulatory unit on inpatient admission rate and length of stay | Audit |

Not recorded | Not recorded |

|

Wang and Ma (2018)

|

Move treatment from inpatient to outpatient model | Quality improvement |

Not stated | Not stated |

Overall, 13 articles described a single-site study (Hordern et al, 2013; Khan et al, 2013; Tompsett et al, 2013; Coleman et al, 2014; McCarthy et al, 2014; Ijaz et al, 2016; McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Wang and Ma, 2018; Ucyigit, 2020; Channing and Doraiswamy, 2021; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023), with one case-controlled study comparing different models of care at two separate sites (Ryan et al, 2019). The studies were based in the UK, Ireland or Denmark and covered 2004–2020, but were published after 2010.

All study settings fulfilled the definition in the inclusion criteria. One study (Ostenfeld et al, 2023) included home management models of hyperemesis gravidarum, seven clarified the location of outpatient care, with six set in day areas of an existing gynaecology ward or gynaecology emergency clinic (Ijaz et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ryan et al, 2019; Channing and Doraiswamy, 2021; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023) and one in maternity services (McParlin et al, 2016). The other articles did not provide a description of the ambulatory care location. Only eight articles noted that the service was ongoing (Hordern et al, 2013; Coleman et al, 2014; Ijaz et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Channing and Doraiswamy, 2021; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023).

Participants, referral patterns and staffing

All the studies described the care of pregnant women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum who met an accepted definition of hyperemesis gravidarum. Demographics described showed heterogeneity in the women's age, gravidity, parity, ethnicity and symptom. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for women with hyperemesis gravidarum were clearly outlined in nine articles (Hordern et al, 2013; Coleman et al, 2014; McCarthy et al, 2014; McParlin et al, 2016; Dean and Marsden, 2017a, b; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ryan et al, 2019; Doherty et al, 2023). All articles stated that care was provided by nursing or midwifery staff with consultation with medical staff available; however, only one article described a multidisciplinary team that offered holistic care (Doherty et al, 2023).

Of the 18 articles, seven described how women accessed hyperemesis gravidarum care, with women referred through multiple pathways, including primary care, emergency department referral, clinician or self-referral. There were different combinations of referral bundles described, with four accepting primary care referrals (Coleman et al, 2014; Ryan et al, 2019; Ucyigit, 2020; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021), four with emergency department referrals (Coleman et al, 2014; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ucyigit, 2020; Doherty et al, 2023), three allowing referrals from midwives or obstetricians (Coleman et al, 2014; Ucyigit, 2020; Doherty et al, 2023), and four accepting self-referrals (Coleman et al, 2014; Ucyigit, 2020; Channing and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023). Ryan et al (2019) specified that women who were referred from primary care could only access the hyperemesis gravidarum service if first-line management with anti-emetics was not successful.

Two of the randomised controlled trials described recruitment pathways, one from the maternity assessment unit and one from an existing outpatient clinic that offered intravenous fluid rehydration (McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b). The two qualitative studies recruited participants through clinic attendance or social media (Dean and Marsden, 2017a, b; Doherty et al, 2023).

Management and treatment

All articles that described outcomes related to clinical management included administration of intravenous fluids and anti-emetic medications (Hordern et al, 2013; McCarthy et al, 2014; McParlin et al, 2016; Dean and Marsden 2017a, b; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ryan et al, 2019; Ostenfeld et al, 2023; Doherty et al, 2023). Anti-emetic medications were described in 12 articles:

One article specified that first-line medications were required prior to programme admission but did not identify the medications. Six articles specified the type of intravenous fluid therapy, with normal saline (McCarthy et al, 2014; Ostenfeld et al, 2023), normal saline with potassium (Tompsett et al, 2013; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b) and compound sodium lactate described (McParlin et al, 2016; Ucyigit, 2020). Five articles described administration of intravenous fluids over 2 hours (Tompsett et al, 2013; McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ucyigit, 2020) or 2.5 hours (McCarthy et al, 2014).

Administration of low molecular weight heparin was described in two records (McParlin et al, 2016; Ostenfeld et al, 2023), and thiamine was directly discussed in three (Tompsett et al, 2013; Coleman et al, 2014; Ryan et al, 2019). Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy (2021) reported that 40% of women with prolonged hyperemesis were not prescribed thiamine. Two further articles mentioned multivitamin administration (McCarthy et al, 2014; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b).

Additional investigations and services were described in some articles. Routine pathology was specifically mentioned and included blood biochemistry in nine articles (Coleman et al, 2014; McCarthy et al, 2014; Ijaz et al, 2016; McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ryan et al, 2019; Ucyigit, 2020; Ostenfeld et al, 2023; Doherty et al, 2023). Six articles included urine testing for ketones or infection (Coleman et al, 2014; McCarthy et al, 2014; McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ryan et al, 2019; Doherty et al, 2023), with two describing ketones as a criterion for eligibility for their intervention (Coleman et al, 2014; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b). Only two articles described specific levels of ketones as a discharge criterion (McCarthy et al. 2014; Mitchell-Jones et al. 2017b). Ultrasound scan was specifically mentioned in six articles (McCarthy et al, 2014; Ijaz et al, 2016; Ryan et al, 2019; Ucyigit, 2020; Ostenfeld et al, 2023; Doherty et al, 2023). Monitoring weight progress was discussed in four articles (McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Ostenfeld et al, 2023; Doherty et al, 2023), and the pregnancy-unique quantification of emesis and nausea score was used in four articles (Tompsett et al, 2013; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023). Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy (2021) noted that this score was not completed in 94% of participants in their review.

Education for women regarding hyperemesis gravidarum was directly discussed in six articles (Tompsett et al, 2013; Dean and Marsden, 2017b; Ucyigit, 2020; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023; Doherty et al, 2023). Medication safety education was highlighted in one article, reporting 80% of all women prescribed ondansetron did not receive counselling about cleft lip and palate (Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021). Staff education was discussed in four articles (Coleman et al, 2014; Dean and Marsden, 2017a; Channing and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023). Women in the outpatient care model reported that they were more satisfied with staff knowledge of hyperemesis gravidarum (73.9% vs 46.3%; P<0.01) compared to the inpatient model (Dean and Marsden, 2017a).

Admissions/length of stay

The reported aim and primary outcome in some articles were to increase the use of the outpatient model. Channing and Doraiswamy (2021) reported that they recruited 40% of eligible women to an outpatient model in their intervention, decreasing inpatient admissions. Coleman et al (2014) found that hospital admissions for hyperemesis gravidarum decreased by 46% during the 6-month study intervention. Wang and Ma (2018) reported a decreased admission rate of 18% and a readmission rate of <0.5% over 6 months and Ijaz et al (2016) stated that the inpatient admission rate for hyperemesis gravidarum decreased from 73% to 10% over 12 months.

Many articles quantified the decrease in the length of hospital inpatient stay for women with hyperemesis gravidarum through increased use of outpatient-managed care. Hordern et al (2013) reported a decrease in 55.9 inpatient hours/month (2.3 days) and McCarthy et al (2014) reported a median difference of 2 inpatient day (2 vs 0; P<0.01). Ryan et al (2019) reported an overall length of stay for women with hyperemesis gravidarum of 1.67 vs 5.67 days (P<0.001) for outpatient management and inpatient care respectively. With adjustment for readmission, this remained statistically significant (0.39 vs 4.08 days, P=0.0002) for women in outpatient care compared to inpatient care (Ryan et al, 2019). Ucyigit (2020) also found a significant reduction in inpatient nights per year (424.5 vs 227.38, P<0.001), and length of stay in nights per admission (1.74 vs 0.89, P<0.0001) when outpatient care was introduced. Tompsett et al (2013) reported a median length of stay of 6 hours with a 61% discharge rate for women receiving outpatient care. One article did not find a difference in length of stay; however, there was a decrease in readmission time for women in the outpatient group (Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b). Another found significant reduction in mean total inpatient time in hours for the outpatient group compared to the inpatient group (27.2 vs 94.1, P<0.001), with 93% of outpatient cases discharged within 12 hours (McParlin et al, 2016).

Women's experiences

The Coleman et al (2014) audit found that 88% of women in the outpatient model were highly satisfied and 100% ‘felt that their concerns were listened to’ and ‘felt better after day care treatment’. Dean and Marsden (2017a) reported that more women in the outpatient model were ‘feeling better’ compared to the inpatient model (85.5% vs 61.4%, P<0.001). Most women in both models preferred an outpatient model of care (n=195, 57%) (Dean and Marsden, 2017a). Two articles reported that women had a better experience in an outpatient model, but these findings were not quantified (Khan et al, 2013; Ryan et al, 2019). The three randomised controlled trials found no significant differences in quality of life measures between outpatient and inpatient care models (McCarthy et al, 2014; McParlin et al, 2016; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b). One quality improvement project reported 100% participant satisfaction with the outpatient model of care (Wang and Ma, 2018). McCarthy et al (2014) reported that women randomised to outpatient care were as satisfied with their care as those in the inpatient care arm (client satisfaction questionnaire median: 63; interquartile range: 58–71 vs median: 67; interquartile range: 57–69). Ostenfeld et al (2023) reported that patient satisfaction was comparable before and after their model change. The two qualitative articles reported similar findings for women's experiences of the two care models (Dean and Marsden, 2017b; Doherty et al, 2023) and highlighted the importance of healthcare professionals that understand and acknowledge hyperemesis gravidarum as a medical condition with significant physical, social, family and employment impacts (Dean and Marsden, 2017b; Doherty et al, 2023).

The importance of hyperemesis gravidarum's impact on women's mental health and the need for appropriate information regarding the condition, management and support provided was identified (Dean and Marsden, 2017b; Doherty et al, 2023). The positive factors associated with an outpatient model included the opportunity to access and engage with multiple types of healthcare professionals, such as dietitians; continuity of care; early intervention for symptom control; provision of a support network; and a feeling of safety (Dean and Marsden, 2017b; Doherty et al, 2023). Both articles highlighted the need for all healthcare staff to be educated on hyperemesis gravidarum, as lack of knowledge or understanding decreased trust in care management (Channing and Doraiswamy, 2021; Doherty et al, 2023).

Economic impacts

Murphy et al (2016) performed an economic evaluation of the randomised controlled trial conducted by McCarthy et al (2014). This evaluation found that outpatient models had a cost saving for both the healthcare service provider and woman of €2852 compared to inpatient care (mean: €985; 95% confidence interval: €705–1456 vs mean: €3837; 95% confidence interval: €2124–8466) (Murphy et al, 2016). The probability of outpatient care being cost effective was 73%, compared to inpatient management of 23% (Murphy et al, 2016). The authors also reported a beneficial increase of 0.07 quality-adjusted life years for the outpatient group compared to the inpatient group (9.42; 4.19–12.25 vs. 9.49; 4.32–12.39) (Murphy et al, 2016). Ucyigit (2020) calculated the potential annual cost saving of outpatient care at £92 669 compared to inpatient care (£199 535 vs £106 866; P<0.0001).

Discussion

This scoping review identified significant gaps in the literature on understanding the ideal model and delivery of outpatient care for hyperemesis gravidarum. The available data covered some outcomes of care, including acceptability of an outpatient model for women and possible cost impacts.

Management and treatment

There was significant variation in the description of hyperemesis gravidarum management and the eligibility criteria for interventions. The exclusion of other contributing factors or underlying causes of hyperemesis gravidarum, such as thyrotoxicosis, was rarely outlined. Although the provision of medications and intravenous fluids was described, there was considerable variation with this and the provision of additional elements of care, such as thiamine and anti-coagulant therapy. Consistency in the approach to inclusion and management pathways for women in models of care is important as it enables clarity of comparison for evaluation. The core set of research outcomes proposed for hyperemesis gravidarum covering clinical care, maternal wellbeing and perinatal outcomes can be used to guide programme evaluation and reporting (Jansen et al, 2020). It is recommended that future research includes a clear definition of hyperemesis gravidarum, with inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation clearly outlined.

The pregnancy-unique quantification of emesis and nausea assessment tool, used to quantify the severity of symptoms of nausea, vomiting and retching a woman may experience within 12 or 24 hours, is an important inclusion for hyperemesis gravidarum identification and management. Only four articles described using this tool (Tompsett et al, 2013; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017b; Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021; Ostenfeld et al, 2023); however, most of the UK articles in this review were undertaken before the release of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists' (2016) guidelines that recommend its use.

Worldwide, the pregnancy-unique quantification of emesis and nausea assessment is endorsed by multiple clinical practice guidelines (Koren and Cohen, 2021). These include published guidelines from Australia and New Zealand (Lowe et al, 2019), the UK (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2021), France (Deruelle et al, 2022), the USA (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2018) and Canada (Campbell et al, 2016). Studies validating this tool have been conducted in non-English speaking countries, such as Norway (Hada et al, 2021), Japan (Yilmaz et al, 2022), Turkey (Dochez et al, 2016) and France (Dochez et al, 2016). Including this or a similar validated assessment tool to monitor treatment efficacy as well as evaluate overall management outcomes in future research is important, as it would enhance the capacity to evaluate and compare data.

The review identified two factors related to safety in prescribing medication for hyperemesis gravidarum: education for staff and information for women. It is concerning that only one article in this review mentioned medication safety (Fernandopulle and Doraiswamy, 2021). Studies have reported that many women cannot access to medications during pregnancy because of prescribing concerns from pharmacists and primary care providers (Madjunkova et al, 2014; Hsiao et al, 2021). The lack of approved indications for these medications in pregnancy may contribute to some pharmacists' and doctors' reluctance for ‘off-label’ use, particularly in the first trimester (Hsiao et al, 2021). Despite the well-documented impact of women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum, symptom control with medication is dependent on the knowledge and willingness of clinicians to prescribe and dispense medications (Tan et al, 2018). Women with hyperemesis gravidarum require information on medications and their safety profiles to create options in the management of hyperemesis gravidarum, preferably in both verbal and written forms in the relevant language (Madjunkova et al, 2014).

International clinical practice guidelines recommend objective parameters for monitoring and discharge, including weight monitoring; however, weight was not mentioned in most of the articles in this review. Weight was acknowledged as a potentially sensitive parameter in only one study (Doherty et al, 2023). When available, most women appreciated access to a dietician and individualised advice (Doherty et al, 2023).

There were differing parameters for discharge outlined in some of the articles, with a lack of consensus on objective measures, such as the level of ketones or pathology parameters for assessment of maternal dehydration. Ketonuria has been used previously as a hyperemesis gravidarum diagnostic criterion (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2016); however, there may be no association between hyperemesis gravidarum severity and level of ketonuria, and its use may lead to increased length of stay (Koot et al, 2020). Given that management of dehydration with intravenous fluids may be outside the scope of primary care, research regarding hyperemesis gravidarum outpatient services require clear parameters for discharge both for clinical safety and consistent communication with women, and to allow comparison of different model of care outcomes to evaluate the literature.

Women's experiences

Women's feedback indicated that those experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum required a high level of emotional and social support from care providers (Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017a; Dean et al, 2018). This review found that women's satisfaction with outpatient models was similar or higher than with inpatient models. Mental health was highlighted as an area where women desired better access to support, correlating with the acknowledgement of the mental health burden associated with hyperemesis gravidarum and its persistent impact on women, even after giving birth (Kjeldgaard et al, 2017). Acknowledging and validating women's distress from hyperemesis gravidarum and providing psychosocial supports is important to minimise the mental health burden that they experience. This would be a significant area where future research could clearly identify the type and frequency of mental health support that women with hyperemesis gravidarum require.

Doherty et al (2023) highlighted that women reported a ‘highly positive’ experience in an outpatient model, valuing continuity of care and a dedicated space that supported their physical and psychological needs. Care environments designed with consideration of sensory input are important, including the ability to dim lights, reduce noise and limit odours, as many women are highly responsive to triggers that may worsen their nausea and vomiting symptoms (van Vliet et al, 2018). Women have identified the provision of comfortable recliners to receive intravenous therapy (Dean and Marsden, 2017a) as well as privacy in a single room (Beirne et al, 2023) as important. These aspects of the physical environment could be further explored in the literature to help service redesign and implementation for hyperemesis gravidarum services.

Outpatient models that provided continuity and a woman-centred approach to care demonstrated the benefits of safety and trust, with two studies specifically mentioning the use of midwifery continuity (McParlin et al, 2016; Doherty et al, 2023). Midwifery-led continuity models of care should be explored further for hyperemesis gravidarum. Perinatal midwifery-led care models are supported by research demonstrating improved satisfaction for both women and professionals as well as reduced financial cost to women and comparable outcomes regardless of obstetric risk (ten Hoope-Bender et al, 2014; Sandall et al, 2016; Boelig et al, 2018).

The International Confederation of Midwives (2014) identified the importance of improved access to appropriate maternity care for women across the reproductive life cycle, including from conception. Models of care such as early pregnancy assessment services have facilitated improved access and provided an alternate pathway from emergency departments for assessment and management of some early pregnancy concerns (Freeman et al, 2023). Midwives' scope of practice is across the continuum of pregnancy and, as such, they are well placed to support women through innovative models of care in pregnancy, including outpatient care models for hyperemesis gravidarum (Watkins et al, 2023). This is an area where further research could significantly contribute to a change in clinical care, with the potential to improve the outcomes of women with hyperemesis gravidarum.

Admissions/length of stay

This review's findings suggest that a decrease in service use can be achieved without negatively impacting management and experience of hyperemesis gravidarum. In one article, cost benefits were assumed with a reduction in hospital use through decreased admissions and readmissions. The included studies reported lower readmission rates than with other published analyses of inpatient care (Nurmi et al, 2022). This is an important area to pursue in future research to understand if an outpatient model could lead to cost savings.

Loss of productivity in the workforce from hyperemesis gravidarum has been correlated with disease severity (Tan et al, 2018). Quantification of the full impact that hyperemesis gravidarum has on a family unit is challenging, as it would need to consider the direct costs of impact on the woman during pregnancy, indirect costs for those who care for her and ongoing impacts in the postpartum period (Piwko et al, 2007; 2013; Trovik and Vikanes, 2016). Inclusion of system costs as part of programme implementation and evaluation should be routine practice for service redesign, as it provides objective evidence for financial viability and sustainability (Juni et al, 2017).

Other studies support the findings that outpatient models of care are sustainable and less costly in comparison to inpatient models (Boese et al, 2019; Dimitrova et al, 2021). Understanding the full economic impacts of an outpatient model of care for hyperemesis gravidarum is an important outcome for evaluation.

Implications for practice

Outpatient services for hyperemesis gravidarum should be considered as an alternative to inpatient care, as they may reduce hospital admissions and length of stay without compromising women's health or satisfaction. Development of standardised, evidence-based protocols for outpatient hyperemesis gravidarum management is required, including consistent approaches to investigations, treatments, and education. Service evaluation should be performed and disseminated.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this scoping review is that it included all types of publications to ensure a comprehensive presentation of the available evidence regarding outpatient models of care for hyperemesis gravidarum. The broad search methodology in multiple databases that included all publication types means it is less likely that significant relevant literature was not identified. The methodology of a scoping review itself is a strength, as the available evidence has been mapped and knowledge gaps and emerging concepts identified.

The limitations of this review include the small number of studies available for analysis. Some of the included studies were reported as conference poster presentations, resulting in a lack of available data. The heterogeneity of the included articles, their methodology and reporting, combined with the lack of data, made it difficult to draw robust conclusions regarding the models of care. Formal quality appraisal was not carried out because of the nature of a scoping review and lack of data, making it difficult to rely on the validity and generalisability of the findings. The geographical location of the studies meant that they were carried out in similar health systems and structures, and this may make findings less generalisable to other health systems or locations.

Conclusions

To the authors' knowledge, this is the only scoping review to report on published data regarding characteristics and outcomes of outpatient models of care for women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Understanding outpatient models of care for hyperemesis gravidarum is an identified research priority. This review has shown that there is a significant lack of published literature reporting on the characteristics of outpatient models and outcomes of care for women with hyperemesis gravidarum. In the future, detailed descriptions of hyperemesis gravidarum outpatient models, including psychosocial care, should be reported so that thorough evaluation can enable system change and improved experiences and outcomes for women.