Exclusive breastfeeding is the optimal nutritional food for newborns and babies under 6 months old (Pérez-Escamilla et al, 2019). Numerous benefits for both babies and mothers, including antibody protection against pathogens for babies, have been reported (Victora et al, 2016; Xu et al, 2024). During the COVID-19 pandemic, Pace et al (2021) demonstrated that breast milk from infected mothers provides valuable antibodies against infection in the infant. Breast milk has also been linked to higher intelligence levels in babies (Lockyer et al, 2021; North et al, 2022) and a lower risk of diabetes and hypertension in mothers (Rameez et al, 2019). Evidence shows that breastfeeding mothers have increased uterine involution (Al Sabati and Mousa, 2019), lower postpartum cholesterol and triglyceride levels (Sattari et al, 2019), reduced ovarian cancer risk (Modugno et al, 2019), increased protection against breast cancer (Borges et al, 2020) and a lifelong positive effect on their health (Muro-Valdez et al, 2023). Breastfeeding has also been associated with savings in healthcare costs and is a cost-efficient economic option for infant feeding (Santacruz-Salas et al, 2019; Walters et al, 2019).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2023) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life to ensure that infants achieve optimal growth, development and health. Globally, approximately 41% of babies are breastfed exclusively for 6 months, and only 45% continue to breastfeed for up to 2 years (WHO, 2022). Breastfeeding rates in the UK are comparatively low relative to many other nations. In comparison to high-income countries such as the USA (27%), Norway (35%) and Sweden (16%), the UK's breastfeeding rate at 12 months is below 1% (Victora et al, 2016), which is attributed to the lack of consistent support and awareness regarding the benefits of breast milk (Mavranezouli et al, 2022). In Australia, while breastfeeding initiation is high at 96%, the most recent data show that only 35% of mothers continue to exclusively breastfeed until their baby is 6 months old (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023).

Women have reported ceasing breastfeeding before their baby is 6 months old for a variety of reasons, including lack of support in the workplace (Cervera-Gasch et al, 2020), sore or painful breasts (Morrison et al, 2019), perceived insufficient or low milk supply (Mohebati et al, 2021), engorgement and cluster feeding (Demirci et al, 2018; Scime et al, 2023), cracked or bleeding nipples (Simpson, 2019) and attachment/latching difficulties (Hornsby et al, 2019).

Inconsistent or confusing advice from midwives and child health nurses has been cited as a significant source of dissatisfaction with breastfeeding support, impacting breastfeeding outcomes (McAllister et al, 2009; Council of Australian Governments Health Council, 2019; Cramer et al, 2021) resulting in women ceasing to breastfeed before they otherwise would have, and prior to the recommended exclusive breastfeeding recommendations with deleterious effects for both mother and baby.

A preliminary scoping of the literature from 2013 to 2023 found that research pertaining to breastfeeding knowledge sources has predominantly focused on maternal experiences, support needs and sources of information (Newby et al, 2015; Burns et al, 2020; Shipton et al, 2023). However, specific sources of breastfeeding knowledge and support skills and how frequently they are used by midwives and midwifery students remains unclear. To address this, a scoping review was undertaken to systematically evaluate existing research on this topic and pinpoint any existing knowledge gaps.

Methods

This scoping review followed Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) framework and adhered to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews guidelines (Tricco et al, 2018). A review protocol was developed and registered with Figshare on 9 May 2024 (#25479334). Consistent with the aim of a scoping review, the authors sought to identify and map the breadth of published evidence available on sources of breastfeeding knowledge and support skills among midwives and midwifery students. The original research question was ‘from which sources do midwives acquire their breastfeeding knowledge?’. This was expanded to encompass breastfeeding support skills and the involvement of midwifery students as there were limited findings in the initial search, resulting in the refined question ‘what insights does the existing literature offer regarding sources of breastfeeding knowledge and the acquisition of breastfeeding support skills among midwives and midwifery students?’.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were estbalished to filter studies and materials written in English and published between January 2014 and April 2024. The search was limited to literature published from 2014 onwards to ensure cover of current evidence on the topic was included. Quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method research methodologies were included, as were studies with mixed populations if they involved midwives or midwifery students. Peer-reviewed publications as well as grey literature were included if they offered a comprehensive description of sources of breastfeeding knowledge and the acquisition of breastfeeding support skills. Exclusion criteria included materials unrelated to sources of breastfeeding knowledge or lacking credibility, such as marketing materials, and non-authoritative opinion pieces.

Search strategy

A multi-source search strategy was used to search electronic databases (CINAHL Plus with full text, Cochrane library, Embase, Medline/PubMed, Google Scholar), citations and reference lists. An exploratory search for additional material published in grey literature included a search in TROVE, WorldCat, Open Grey, Analysis and Policy Observatory and Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. The search was expanded to explore grey literature and included existing networks and relevant organisations (International Confederation of Midwives, Australian College of Midwives, Royal College of Midwives, Australian Breastfeeding Association) as well as social media platforms (Instagram, Facebook). With social media becoming an increasingly popular platform for sharing academic knowledge (Ojukwu et al, 2021), it can potentially provide sources of breastfeeding knowledge and skills for midwives and midwifery students. This broad spectrum of relevant grey literature sources was incorporated as valuable evidence to strengthen the rigor and reliability of the study findings (Paez, 2017).

To ensure a comprehensive search strategy, a librarian was consulted for initial guidance and assistance. The strategy was tested on the CINAHL Plus with full text database before being adjusted for subsequent databases. The keywords used were ‘midwives’,‘midwifery students’, ‘midwifery’, ‘breastfeeding’, ‘sources’, ‘education’, ‘knowledge’, ‘information’, ‘workshop’, ‘development’, ‘bootcamp’, ‘instruction’, ‘training’, ‘upskilling’, and ‘in-service’. Boolean operators were used to optimise search results.

Screening

Initially, one reviewer screened search results based on titles, followed by screening of abstracts and full-text review by four reviewers to determine study eligibility for inclusion in the review. Any disagreements in study selection and data extraction were resolved through discussion and consensus among the research team.

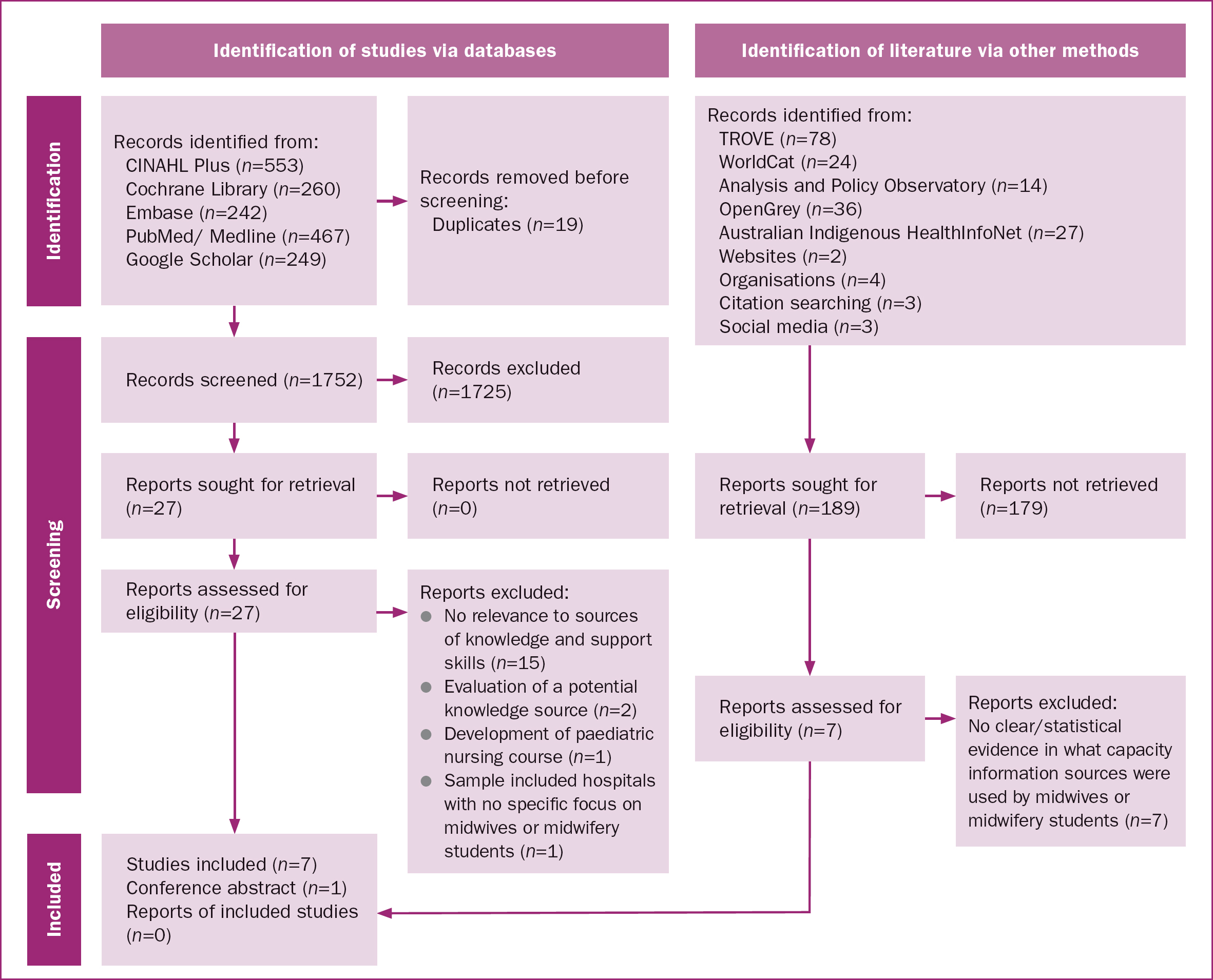

The search results yielded a comparable number of articles across databases (Figure 1), and the manual search of citations and reference lists identified three additional studies. In total, 179 relevant results were generated from various grey literature sources. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 1752 studies were screened. A total of 27 full-text articles were assessed, of which 19 were excluded, such as studies lacking the exploration of breastfeeding sources and skills for midwives or midwifery students. As this was a scoping review, no quality appraisal was performed.

Results

The scoping literature review yielded seven research studies and one conference abstract.

Study characteristics

A data extraction sheet was developed to summarise article characteristics (Table 1). Of the seven included studies, one was conducted in Australia (Hartney et al, 2021), one in Ghana (Dubik et al, 2021), one in Poland (Nehring-Gugulska et al, 2015), one in the USA (Grabowski et al, 2021), and three were conducted in the UK (Angell et al, 2015; Ssengabadda, 2017; Spencer et al, 2022). The eighth included paper was a published Australian conference abstract (Garland and Wright, 2022).

| Reference and country | Design, instrument and sample | Main outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angell et al, 2015 UK | Quantitative survey of n=178 midwives, students, mothers and pregnant women |

|

|

| Dubik et al, 2021 Ghana | Quantitative cross-sectional survey of n=104 nurses and midwives | ||

| Garland et al, 2021 Australia | Conference abstract on workshop with midwives | Workshop aims to equip midwives with tools from South Western Sydney Local Health District Breastfeeding Bootcamp, enhancing ability to maintain breastfeeding, address related challenges and effectively problem solve | Workshops are sources of knowledge and skills for healthcare professionals and community members in a local health district |

| Gabrowski et al, 2021 USA | Sequential explanatory, mixed methods (questionnaire and focus group) with n=9 nurse-midwifery students |

|

Classroom lactation simulation in midwifery curriculum enhances students’ knowledge and skills |

| Hartney et al, 2021 Australia | Proof of concept, cross-sectional study with quantitative and qualitative approach with n=106 midwives (n=81) and midwifery students (n=25) |

|

Instructional video which used in midwifery curriculum at Deakin University is effective in providing complex breastmilk physiology knowledge |

| Nehring-Gugulska et al, 2015 Poland | Quantitative questionnaire with n=361 midwives, nurses, doctors, pedagogue/psychologist other health professionals |

|

Programmes and postgraduate courses are effective sources of knowledge for practitioners who provide breastfeeding support |

| Spencer et al, 2022 UK | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) with n=17 final year midwifery students |

|

University curricula are source of knowledge and support skills for midwifery students. There are challenges and scope for improvement as modules did not prepare students for complexity of clinical practice and linking theory to practice |

| Ssenabadda, 2017 UK | Exploratory qualitative, focus group with n=8 final year midwifery students |

|

All participants did a breastfeeding module in first year of university training with both theory and practical workshops. Classroom learning did not reflect range and reality of challenges faced in real life support. Majority had learnt more in practice, while teaching and supporting women to breastfeed, than at university |

Sources of breastfeeding knowledge and support skills

The findings ranged from clear study findings to vague and tangential evidence related to the review question. Only one study, conducted in Ghana, provided a direct and comprehensive analysis of sources of breastfeeding knowledge and breastfeeding support skills (Dubik et al, 2021). The 104 surveyed midwives and community health nurses provided maternal and child healthcare in antenatal clinics, child health clinics and maternity wards, with the majority (70%, n=73) working in urban locations. The study reported that while most participants (83%, n=87) had pre-service training, 64% (n=67) cited in-service training as their primary source of breastfeeding knowledge. In contrast, just 25% (n=26) of the study population viewed their pre-employment training as their main source of breastfeeding knowledge, while 11% (n=11) drew from their personal experience. A large proportion of nurses and midwives (68%, n=69) identified posters, leaflets and books as their primary source of information, followed by academic journals (17%, n=17), conversations with colleagues (11%, n=11), the internet (3%, n=3) and media (2%, n=2). The overwhelming majority (80%, n=83) of Ghanaian nurses and midwives believed they required additional training on breastfeeding.

Education programmes

Three studies presented educational programmes as effective breastfeeding knowledge sources for midwives and midwifery students. A Polish study conducted a quantitative survey of midwives, nurses, doctors, educators, psychologists and other healthcare professionals (n=361) with 70% (n=253) working in hospital maternity units (Nehring-Gugulska et al, 2015). The test sample of 168 participants had completed a professional development course in breastfeeding knowledge, whereas the control sample of 193 participants had not, but obtained breastfeeding knowledge exclusively as undergraduates. A 10-point test was administered to both groups to assess lactation knowledge, categorised according to Wellstart International guidelines. The likelihood of achieving a high score was found to be higher when participants completed a professional development course in breastfeeding knowledge (odds ratio=8.73), underwent the most extensive training in breastfeeding support skills (odds ratio=4.80) or obtained International Board of Lactation Consultant Examiners certification (odds ratio=5.07). In the test sample, medical doctors and professionals from other fields achieved the highest mean scores. Conversely, nurses in perinatal departments and midwives with undergraduate education achieved the lowest mean scores.

Spencer et al (2022) interviewed 17 final-year UK midwifery students, and highlighted that while university curriculums were one source of breastfeeding knowledge, good supervisor-student relationships during clinical placements boosted students’ confidence with breastfeeding support. In contrast, students highlighted a lack of support and disinterest from hospital-based midwives, with one student expressing doubts about providing breastfeeding support after completing her qualification. The majority of midwifery students’ struggled to connect breastfeeding theory from their course with its practical application in the clinical setting. Students reported receiving extensive theoretical knowledge about breastfeeding during their first year of study, but felt they lacked adequate practical training in breastfeeding skills. They also noted a deficiency in practical guidance from the university regarding supporting mothers in infant feeding choices. Additionally, they emphasised the necessity for more opportunities at university to develop technical and relational skills, particularly to manage complex situations.

Similar findings were presented by Ssengabadda (2017) who interviewed eight final year midwifery students in the UK. The author noted that the breastfeeding module taught in the first year of the midwifery curriculum, which included theory and practical workshops, did not sufficiently prepare students for the diverse challenges of breastfeeding support encountered in practice. As a result, the majority of students reported they gained more practical knowledge by teaching and supporting women to breastfeed than they did during their university education. Some participants identified prior breastfeeding knowledge from personal experience or previous employment as a valued source of information, which they argued was reinforced and consolidated when they acquired new information and skills on exclusive breastfeeding as midwifery students. In general, midwifery students expressed a desire for increased practical exposure in exclusive breastfeeding teaching and preferred interactive learning methods, such as roleplaying and hands-on activities, over theory-based activities or completing workbooks.

Additional educational resources

Three studies and one conference abstract focused on specific educational tools as sources of breastfeeding knowledge. Grabowski et al (2021) piloted lactation simulation workshops on nine nurse-midwifery students in the USA, which were integrated into the curriculum in contrast to traditional didactic learning. This mixed-methods study reported a 14% increase in perceived self-efficacy in basic and advanced clinical lactation skills. The results also revealed that most students (n=5) expressed a desire for additional practice time in simulated clinical lactation skills, with some (n=2) specifically seeking more exposure to challenging breastfeeding concerns compared to common ones.

Hartney et al (2021) examined the ‘Breastfeeding Hormones in Play’ instructional animation video, which was used in the midwifery curriculum of an Australian university. Participating midwives overwhelmingly reported the video as a valuable learning resource, with 96.3% (n=77) finding it complementary to other breastfeeding resources. Midwifery students expressed a very high level of support for the, resource with combined agreement levels exceeding 95%. The study also found that 80% of student participants (n=20) relied solely on their course for breastfeeding education, without seeking additional sources of information.

Garland and Wright (2022) highlighted workshops as an effective educational tool for sourcing breastfeeding knowledge. The workshops, modelled after highly successful breastfeeding bootcamps in one Australian health district, focused on evidence-based foundational skills and aimed to enhance breastfeeding knowledge. Angell et al (2015) examined Healthtalk.org, a UK-based website that featured breastfeeding-related content presented through video interviews and factual evidence-based information on its webpages. A wider audience was targeted by identifying the resource users of Healthtalk.org, their roles and their opinions on breastfeeding. A total of 178 responses were collected, with 83.7% originating from users in the UK. While most respondents were students, 26% were mothers or pregnant women. The study did not specify whether the students included both nursing and midwifery students and how many midwives participated. The majority of respondents visited the website for educational resources (67%). More than half (56.1%) intended to apply the knowledge acquired from the webpages. It was not clearly stated whether this figure included midwives or midwifery students.

Grey literature

Alongside peer-reviewed journal publications from electronic databases, grey literature from relevant organisations, including the International Confederation of Midwives (2024), Australian College of Midwives (2024), Royal College of Midwives (2024) and the Australian Breastfeeding Association (2024), provided information regarding essential educational tools crucial for midwifery practice in promoting breastfeeding. Two websites that provide breastfeeding knowledge and support skills for midwives and midwifery students were also identified (All 4 Maternity, 2024; The Milk Meg, 2024), although this does not encompass all available resources. The content of these organisations and websites emphasised evidence-based practices and global initiatives aimed at supporting midwives and midwifery students in their role as advocates for breastfeeding (Table 2). They provided breastfeeding education via workshops, eLearning modules, classes, webinars, seminars, diploma courses, newsletters, podcasts and blogs.

| Source | Details |

|---|---|

| International Confederation of Midwives (2024) | Currently representing over 136 midwives’ associations in 117 countries – more than one million midwives globally. Professional developmen (breastfeeding) and networking |

| Australian College of Midwives (2024) | Educational tools (over 100 hours of free short courses and webinars that include breastfeeding knowledge, access to midwifery events, scholarships). More than 5000 midwife members |

| Royal College of Midwives (2024) | Over 50,000 midwives, student midwives and maternity support workers who together are the largest and strongest maternity organisation in the world. Sources of breastfeeding information |

| Australian Breastfeeding Association (2024) | Leading provider of breastfeeding education in Australia (workshops, eLearning modules, classes, webinars, seminars, diploma course, newsletter). 1,171 health professionals, from >150 countries, engaged in ongoing breastfeeding education. 1.4 million website users |

| All4Maternity (2024) | Resource for maternity workers, student midwives, midwives, parents and families across the globe. over 50 e-modules, newsworthy blogs and educational podcasts with midwifery influencers |

| The Milk Meg (2024) | Educational resources on breastfeeding for midwives, students and parents |

| student_midwife_studygram (Instagram) | Sources of breastfeeding knowledge and support (educational content, study tips, and resources related to midwifery and breastfeeding) for midwifery students |

| The Breastfeeding Co-operative Australia (Facebook) | Breastfeeding information by and for midwives, pharmacists, counsellors, nurses, researchers, doulas, and others |

| Breastfeeding and Medication (Facebook) | Guidance and assistance for healthcare professionals and mothers related to breastfeedin and potential risks associated with medication exposure through breastmilk |

Insights from social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook highlighted the role of digital communities and professional networks as sources of sharing best practice breastfeeding knowledge and fostering ongoing education among midwives and midwifery students (Table 2). Student_midwife_ studygram on Instagram served as a valuable resource for midwifery students seeking breastfeeding information, offering educational content including resources and study tips. The Breastfeeding Cooperative Australia, a source of breastfeeding knowledge on Facebook, was established by a dedicated group of women, including midwives, and other health professionals. The Facebook site Breastfeeding and Medication offered information and support to healthcare professionals and mothers navigating the balance between the benefits of breastfeeding and concerns about potential medication exposure through breastmilk. These examples illustrate just a few social media platforms commonly used for breastfeeding information by midwives and midwifery students. However, the majority of websites and social media platforms are geared toward pregnant women, mothers and their families.

This integrative search approach underscores the importance of diverse knowledge sources in equipping midwives and midwifery students with updated information and strategies to enhance maternal and infant health outcomes through effective breastfeeding support. However, it was beyond the scope of this study to gather statistical information from organisations, websites and social media platforms regarding the extent to which midwives and midwifery students use these sources.

Discussion

Successful breastfeeding relies on consistent guidance from midwives and midwifery students, who play a central role in supporting mothers throughout their breastfeeding experience. This scoping review examined sources accessed by midwives and midwifery students to acquire breastfeeding knowledge and support skills, investigating pathways and methodologies found in academic and grey literature. The review included seven peer-reviewed articles, and one conference abstract, supplemented by information from grey literature.

The findings highlight a significant gap in current literature, as only one study specifically examined sources of breastfeeding knowledge among midwives and midwifery students. On-the-job training experience emerged as the primary learning source. Sandhi et al (2023) found that during clinical practicums, where students interact with real patients, critical thinking skills and problem-solving skills are developed, as well as planning and monitoring strategies, resulting in improved learning outcomes. This calls into question whether on-the-job training receives the necessary attention in clinical settings where time constrains and staff shortages can limit learning opportunities (Tamata et al, 2021). While posters, leaflets and books were identified as a significant source of breastfeeding knowledge in Ghana, their popularity may be influenced by the dearth of other learning opportunities.

Most reviewed studies identified educational programmes as sources of breastfeeding knowledge and support skills, where challenges in translating theoretical university teachings to practical application were emphasised. This was also reported by Campbell et al (2022), who stated that hands-on experiences to develop student support skills in breastfeeding are lacking. Their findings uncovered a paucity of evidence on how breastfeeding knowledge translates into practice, and the specific time, resources and learning methods needed to effectively cultivate foundational knowledge, positive attitudes and skills in supporting parents in achieving their infant feeding goals. The authors also identified a lack of consistent approaches to breastfeeding education, which requires addressing to ensure more uniform care provided by midwives and midwifery students supporting breastfeeding mothers (Campbell et al, 2022). The present review's findings revealed that effective educational tools, such as simulation workshops, instructional animations and online resources, are crucial in equipping midwives and midwifery students with the necessary skills to support breastfeeding. Similarly, Campbell et al (2022) demonstrated that a wide range of teaching methods and the use of experimental learning enhanced acquisition of breastfeeding skills.

The findings from the present review revealed that numerous breastfeeding promoting organisations use various platforms including workshops, eLearning, webinars, seminars, diploma courses, newsletters, podcasts and blogs to promote continuous learning. Insights from social media platforms underscore the importance of digital communities and professional networks in sharing best practices and fostering continuous education among midwives and midwifery students on breastfeeding. The challenge remains to optimise and streamline educational efforts through consistent multidisciplinary collaboration and adherence to best practice standards for the benefit of consistency in breastfeeding support.

Implications for practice

On-the-job training as a primary source of breastfeeding knowledge, as well as various educational programmes, are critical for improving breastfeeding education and support. The findings revealed a need for more structured and consistent training approaches. Healthcare institutions and educational programmes should consider integrating standardised, evidence-based, interactive and accessible breastfeeding support tools into their curricula and training, such as simulation workshops, animation videos and online resources. The role of online platforms and social media as supplementary resources could be leveraged more effectively to ensure midwives and midwifery students are well-equipped with up-to-date, evidence-based information. Addressing these gaps could improve the quality of breastfeeding support provided by midwives and midwifery students, ultimately reducing the incidence of early discontinuation of exclusive breastfeeding caused by conflicting advice from healthcare professionals.

Limitations

Limiting the scoping literature review to studies published in English may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant research published in other languages.

Conclusions

While there are abundant resources providing education, information and guidance on breastfeeding knowledge and support skills for midwives and midwifery students, this scoping review revealed a notable gap in the literature concerning how extensively these resources are used. Understanding the use of these resources is crucial in addressing inconsistent advice provided to breastfeeding mothers.