It is reported that a growing number of people are moving away from the traditional norms of gender, and identifying themselves as transgender and non-binary. In 2018, UK statistics saw a rise of 53.2% of parents who identified as LGBTIQA+ (Gabb and Allen, 2020). The term ‘transgender’ describes people who identify with a gender different from that assigned at birth (Berger et al, 2015). The term ‘non-binary’ refers to people who identify as either male, female or neither (Jennings et al, 2022). In addition to these two definitions, there are people who have a fluid gender identity, but to encompass the range of groups of people who identify as neither male nor female, they usually identify as non-binary (National Centre for Transgender Equality, 2016). A full glossary of terms is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Asexual | A sexual orientation that encompasses no or little sexual attraction | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Bisexual | Sexual or romantic attraction to people of the same and other genders (it is important not to assume that there are only two genders) | Flanders et al, 2016 |

| Cisgender/Cis | A person that identifies with the binary gender that they were assigned at birth | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Cisgenderism | An intentional or unintentional discriminatory social or structural view. Cisgenderism is the belief that gender identity is determined at birth and a fixed identity based on binary biological sex characteristics | Transhub, 2021 |

| Gay | A male sexually or romantically attracted to other males | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Gender fluid | A person who shifts with their gender | Robinson et al, 2014 |

| Gender identity | A person's sense of whether they are male, female, non-binary, agender, genderqueer or genderfluid. A notion that gender can be binary (male/female) or non-binary (people who do not identify with any gender) | TransHub, 2021 |

| Gender pronouns | Words that a person wishes to be expressed as. For example, she/her or their/they | Rainbow Health Australia, 2016; Johnson et al, 2020 |

| Gender questioning | A person who is unsure of the gender that they identify with | TransHub, 2021 |

| Heteronormativity | A view that heterosexual relationships are normal relationships, excludes anybody that does not identify within the binary gender form | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Heterosexual | A person sexually or romantically attracted to the opposite gender | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Lesbian | A woman sexually or romantically attracted to other females | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| LGBTIQA+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer or questioning, asexual and other sexually or gender diverse | TransHub, 2021 |

| Midwife | A registered health professional who works in partnership with women to give support, care and advice during pregnancy, birth and in the postnatal period. The role of the midwife differs internationally, but is grounded in women-centred and evidence-based maternal care and midwives are integral part of maternity care | Department of Health and Aged Care, 2021 |

| Misgendering | When a person is not addressed using the language, they have chosen to match their gender identity, for example, incorrect pronouns. | Rainbow Healthcare, 2016 |

| Non-binary | The umbrella term that describes a person that sits outside or across the spectrum of the male and female binary | TransHub, 2021 |

| Pansexual | A person who is sexually or romantically attracted to others, not restricted by gender | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Queer | A range of sexual orientations and gender identities used as an umbrella term to encompass all LGBTIQA+ persons | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Service user | A birthing person accessing maternity care | |

| Sex | A grouping made at birth in binary male or female, based on external anatomical features | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

| Transgender | Umbrella term for those whose birth-assigned sex does not match their gender identity. They may or may not surgically or medically modify their bodies, and have the same sexual orientations as the heteronormative population | |

| Trans | People who adopt various gender pronouns; incorrect pronouns are disrespectful and seen as a form of misgendering | Child Family Community Australia, 2022 |

The health experiences of sexual and gender minority people are a contemporary topic, with midwives positioned to play a crucial role in the health experiences of all people that access maternity services. There is a wealth of international literature that explores the point of view from the service user, being the LGBTIQA+ community, which is essential. However, to be able to create a truly inclusive environment for all people that access maternity services, investigating the perceptions of healthcare professionals that provide care is equally important.

There are currently limited studies that investigate the use of gender-neutral language in maternity settings. This narrative literature review aimed to examine the use of gender-neutral language in maternity settings and collate the literature available, to expose any knowledge gaps.

Methods

A preliminary search of the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and MEDLINE databases was undertaken to identify articles relating to the topic. Search terms or text words contained in titles, abstracts and keywords of relevant articles were used to develop a complete search strategy. Words used to develop the search were: ‘midwife, midwives or midwifery’, ‘gender-neutral language’ and ‘perceptions, attitudes, opinion or experiences.

Selection criteria

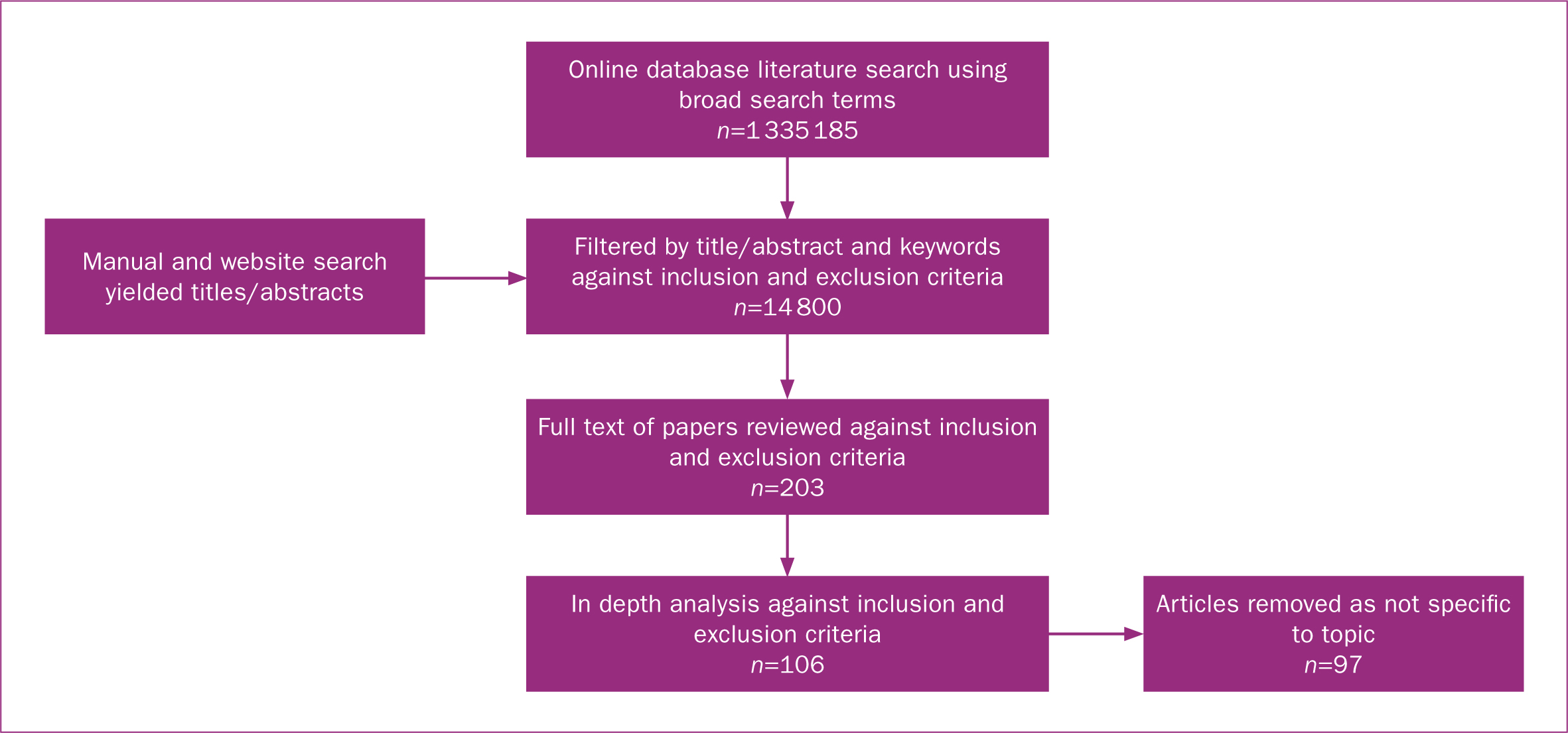

Any relevant literature retrieved from the search was included for reviewing. Only literature or studies conducted within the last 10 years were included. As a result of the limited literature retrieved, primary research and literature reviews were used in this review. Studies that involved the LGBTIQA+ population, healthcare professionals and where gender-neutral language was used in any type of clinical practice were included. The sources were largely qualitative; however, some quantitative articles were included to examine demographics and introduce a broader perspective. The full PRISMA diagram for study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Data analysis

This scoping review was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for scoping reviews and uploaded to RAYYAN© (41). All papers involving an aspect of maternity services were selected for inclusion and screened for eligibility, by title, abstract and full text review, by four independent reviewers against the inclusion criteria. Theme mapping was conducted, and the themes were synthesised into categories.

Results and discussion

Gender-neutral language

Language and gender studies have been a scholastic enquiry in western cultures since the mid-1970s (Mills and Mullany, 2011). Gender can be limited to the binary and the individual level of a person's characteristic, or it can be an all-encompassing range of genders within a structural and interactional level of analysis (Anderson, 2005; Cannon et al, 2015; Messinger, 2017). This field of research leads to a discussion of the Women's Movement and emergent feminist theories, starting with Brubaker (2021), who reported in their commentary that it is essential not only to embrace feminist theory but to expand it and develop new ways of thinking. For example, there have been four historical waves of feminist theories. The first wave was liberal and radical, which has different epistemological assumptions, but shares fundamental ontological assumptions of women's oppression (Manning, 2022). This theory raised concerns of equality and sought solutions to how men and women could exist together without oppression or subordination (Gherardi, 2003; Calas and Mirich, 2006).

Alternative ontologies and worldwide views then began to enter the feminist discourse. The second feminist waves produced socialist and poststructuralist theories that suggested gender to be a socially systematic process, produced through societal power, history and dominant discourses, with institutions becoming enfranchised as ‘the way it is’ (Calas and Smircich, 2006; Manning, 2022).

Post-feminism was the third and fourth wave (Ozkazanc-Pan, 2019). While each wave had a different ontological and epistemological assumption, the third and fourth waves of feminism saw the integration of the alternative lived experience, such as the experiences of questioning gender and gender binaries, where knowledge and experiences were understood to be socially and culturally situated (Hooks, 1981; Haraway, 1988; Mohanty, 2005; Calás and Smiricich, 2006).

Multiple theories argue that gender and sexuality are linked systems of oppression that seek to enforce a gendered social structure, which places women in the home, encompassing motherhood, and promotes men's access to power and resources (Gamson, 1995). Everett et al (2022), argued that structural sexism and structural LGBTIQA+ stigma were inherently linked systems of oppression that establish structural heteropatriarchy, because they reinforce the dominance of traditional heterosexuality. This punishes men and women who do not embody the heterosexual norm.

A narrative of the word ‘sex’ is that humans are sexually dimorphic (Griffin et al, 2021), either male or female. Gender is a societal system that varies over time and location and involves shaping behaviours deemed appropriate for one's sex (Ashley, 2019). Griffin et al (2021) concluded that gender operates instinctively via social norms. When sex refers to biology and gender to socialisation, gender identity can be psychological (Steensma et al, 2018).

The concept of gender identity has evolved since the 1960s (Money, 1994) to include those who do not identify as female or male: a person's self-concept of their gender, regardless of sex, is called gender identity (Lev, 2013). The foundation of gender identity is a multiform phenomenon, and the multiplicity of gender expression argues against a simple or unitary explanation (Lippa et al, 2014). Gender theorists suggest that everyone has a gender identity, which is not variable (Griffin et al, 2021). The Gender Identity Development Service (1998) discussed gender fluidity and gender fluctuation in gender identity that is also recognised, with categories such as ‘non-binary’ and ‘gender fluid’ (Bonfatto and Crasnow, 2018)

Strong societal norms surrounding gender identity are shifting (Parker et al, 2023). This is because of the developing knowledge of rights to fertility among trans and non-binary people, and the development of education on issues related to the health of LGBTIQA+ people (Brandt et al, 2019). In the perinatal period, existing health inequalities can be heightened by the norms and biases that surround parenting, increasing vulnerability, unmet needs and lack of trust and engagement in perinatal services (MacDonald et al, 2016; Hoffkling et al, 2017; Garcia-Acosta et al, 2019; Malmquist et al, 2019; Singer et al, 2019).

Considerations of gender-neutral language often focus on altering only female-specific language, rather than adjusting male-associated words (Dahlen, 2021). Gender-neutral language risks confusing people; as gender-neutral language is intended to include all LGBTIQA+ people, so clinicians should reflect on any disproportionateness in what language is adopted (Quann, 2020).

Etymology and the origins of language in maternity

It is important to ascertain and examine the history in which language is developed. ‘Midwife’ is a word that has been historically linked to a female-dominated profession, acknowledged by the general population as supporting women throughout pregnancy, labour and the immediate postpartum period (Madlala et al, 2020). This is because, historically, midwifery services focused on women with accompanying etymology, such as maternity (maternal being from the French ‘maternal/maternelle’, itself from Latin ‘maternus’, from mater, meaning ‘mother’) (Darwin and Greenfield, 2019).

The word midwife is derived from Middle English; it can be broken down into two elements, ‘mid’ and ‘wife’ (Mair, 2022), with ‘wife’ meaning ‘woman’ and the prefix ‘mid’ meaning ‘together with’ (Oxford Languages, 2022). The etymology of obstetrics is from the Latin source ‘obstetrix’, which can also be broken into two elements. The verb ‘obstare’ means ‘to stand in front of’ and is used with the feminine suffix ‘trix’ (American Heritage Dictionary, 2022). It is also important to acknowledge the legally protected nature of the name midwife in many countries, for example, the UK (Peate and Hamilton, 2014).

Midwifery has been documented for over 800 years as a profession provided by women for women; that is supported in the history of lexicography, as there is no supported terminology for a male midwife (Donnison and MacDonald, 2017). The male role in maternity care originally centred entirely on labour, intending to expedite what men widely regarded as a risky mechanical process (Pendleton, 2019). Men that entered the profession of ‘midwife’ were known as ‘man-midwives’ (Donnison, 1977), leading to the male scope of practice focusing on pathology and intervention. In today's world, this is professed as an obstetrician and reflects that medical model of care (Angstmann et al, 2019).

Taking this into account, the midwife's purpose has traditionally been to assist childbearing women; however, the International Confederation of Midwives (2017) reported that a midwife's philosophy should focus on the commitment to providing flexible, empowering and supportive care of all, which includes LGBTIQA+ people who access maternity services. This acknowledges the growing number of individuals who identify as part of the LGBTIQA+ community (Toze, 2018).

For a person who does not identify as woman or female, there does not seem to be a universally accepted word that embodies the process of pregnancy, birth or childbearing. One qualitative study interviewed 10 non-binary people about their familiarity with accessing maternity services and reported that at least nine different terms were used to refer to their gender identity (Hoffkling et al, 2017). Silver (2019) suggested that inclusive language for maternity services would work better as an additive. Therefore, instead of removing the word ‘women’, the Brighton and Sussex NHS Trust published the first guidance in the UK that included gender-neutral language (Green and Riddington, 2020). This guidance used a ‘gender-additive approach’ to language to ensure everyone was represented to provide what could be perceived as an all-inclusive model of care.

The Brighton and Sussex NHS Trust guidance did not address the word ‘midwife,’ proposing it sits at the restraints of what the word ‘midwife’ can do to accentuate or erase gender (Green and Riddington, 2020). Conversely, transgender and non-binary people require care that matches their bodies, but may not wish to be designated by words that mention their biological sex (Dahlen, 2021).

Gender-neutral language should be established when choosing complementary vocabulary (Dahlen, 2021). For example, maternity care is accessible between 22 weeks' gestation and up to 7 days after birth. ‘Maternity’ denotes a female person in the process of pregnancy and childbirth, whose medical needs may span pre-pregnancy, as well as antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care (Dahlen, 2021). The Brighton and Sussex NHS Trust's suggested using the word ‘perinatal’ instead of ‘maternity’; however, this may risk confusion around medical context and accuracy (Dahlen, 2021). As a separate phenomenon, reproductive biology and personal identity are essential to medicine and research (Mauvais-Jarvis et al, 2020).

The effects of language in maternity

Maternity services are beginning to acknowledge that not all pregnant and birthing people are women, and to ensure that the model of care provided is inclusive (Parker et al, 2023). However, given the identified gap in research of healthcare providers' views, this may be difficult to implement. This positions midwifery's women-centred philosophy as a unique challenge. Ross and Solinger (2019) suggested that when introducing gender-neutral language, there is a vulnerability involved when removing the word ‘women’, as this will affect the lived experiences of women. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health reported that the trans health movement is making gains in securing healthcare rights for the population and challenged midwifery to meet the cultural needs of the LGBTIQA+ population (Parker et al, 2023).

Bradfield et al (2018) piloted an integrative review of the meaning of ‘with woman’, and reported that being ‘with woman’ is a philosophy of midwives' identity, and pursued an analysis of the phenomenon across 32 papers. The authors explained that the terms ‘midwife’ and ‘with women’ have more than an etymological significance, but also provide midwives with a philosophical framework that allows them to focus on the needs of each individual birthing person.

The epistemic tensions between obstetric and maternity professions have significantly been explored in midwifery journals, and centre around the importance of language (Pendleton, 2019). Zeidenstein (1998) posited that inhibiting and symbolising language in maternity has been immortalised by the medical model of care and the obstetric team. Language in maternity should not occupy an imaginary social reality, as social constructionism is an epistemology that allows a freedom of choice for maternity healthcare professionals to provide individualised care and could create an agenda that is understood worldwide (Pendleton, 2022).

There is an increase in published evidence that addresses the gendered meaning of midwifery language, and this literature centres around an additive approach to encompass all birthing persons, without interrupting midwifery philosophy and history, and without the erasure of women (Pendleton, 2022). The etymological significance has yet to be addressed, but ‘gender-neutral’ language refers to service users by using the words ‘client’ and ‘childbearing family’, to emphasise the importance of the etymological orientation device of the word ‘mid’ (Pendleton, 2022).

Women-centred midwifery is perceived as a group of gender-critical individuals, with an appreciative perspective of a person as a sexually dimorphic species, when it comes to all things maternity (Hyde et al, 2019). A person with the ability to give birth is defined as a woman regardless of the gender that person identifies with. The same logic that supports gender-inclusive language for transgender people should apply to women who may feel erased by language that takes a neutral approach (Dahlen, 2021). The aim is to amplify respect for everyone. Therefore, language should follow that females who identify as women cannot be expected to adhere with language in which they do not exist (Ross and Solinger, 2019).

Kerppola et al (2019) reported that empowerment came from recognition. Using a qualitative inductive content analysis, Kerppola et al (2019) interviewed 22 participants who identified as LGTBQ, and summarised that co-operation, interaction, respecting parents' autonomy, equity and gaining parents' trust as healthcare professionals revealed knowledge of the family's unique needs.

Attitudes

Since the late 20th century, midwives have upheld that language matters (Pendleton, 2022). Current midwifery practice has changed to include people who identify within the LGBTIQA+ population with female reproductive organs and, therefore, can get pregnant and give birth (Obedin-Maliver and Makadon, 2016). One integrative review identified heteronormativity as a pre-dominant approach in healthcare settings, with the language used by midwives as a critical factor (Stewart and O'Reilly, 2017). A positivist view of maternity has led to a technocratic approach that sees the birthing body as a systematic process rather than holistic and stems from a male-dominated obstetric model of care (Pendleton, 2019).

LGBTIQA+ inclusion is premised on the human rights of all people to feel safe and receive inclusive care and evidence-based quality sexual and reproductive healthcare (Coleman et al, 2022). Whatever a birthing person's gender, the idea of midwives being with women is widespread and universal (Wickham, 2018). Tuohy (2022) states in an article that transgender spokespersons say that inclusion can be achieved without erasing the term women. Representing everyone who gives birth from a diverse cultural and linguistic background is possible.

Perry (2021) reported that pregnant women, birthing women and new mothers have unique vulnerabilities that require protection. Dahlen (2021) also suggested that pregnancy, birth and motherhood are fundamentally sexed, not gendered issues. Expanding on this, Dahlen (2021) reported that confusing gender identity and the reality of sex risked adverse health consequences and more discrimination against women. In maternity services, gender is commonly conceptualised in ways that combine sex characteristics, such as a female having a uterus, with a gender role or expression of women (Pergadia, 2018). For someone who can be pregnant and give birth, they are, biologically, a woman (Parker et al, 2023). Conversely, gender essentialism does not include people born with a variation in sex or people that identify differently from a sex assigned at birth (Skewes et al, 2018). Gender essentialism has been appraised for how it has emphasised discourse about birth in ways that have led to challenging constructions of good and bad mothers (Kurz et al, 2020).

In a mixed-method cross-sectional study conducted in Australia by Bennett et al (2017), verified questionnaires were completed by 51 nurses and allied healthcare professionals. This is one of the few studies performed from the healthcare provider perspective. Through statistical analysis, Bennett et al (2017) found no significant relationships in knowledge, attitudes and gay affirmative practice scores by sociodemographic variables or professional groups. In Bennett et al's (2017) study, the questionnaire collected free-text qualitative data, analysed thematically. One of the six themes discussed was management; participants felt that there needed to be a shift in healthcare paperwork and that there was no flexibility to enable appropriate gender identification (Bennett et al, 2017). This is applicable information because it was not healthcare professionals' attitudes that affected parents, but the formal language used in paperwork. Additionally, this study focused on established families, not on healthcare providers that were providing care.

In a study examining attitudes from healthcare professionals' perspectives in Turkey, Bilgiç et al (2018) carried out a descriptive cross-sectional study in two nursing and one midwifery school. The surveys gathered students' personal demographics and asked open-ended questions, with responses analysed using the ‘attitudes towards lesbians and gay people scale’, originally designed by Herek (1998). Bilgiç et al (2018) found a negative correlation between attitudes to lesbians and gay people, but only among nursing students; student midwives displayed positive attitudes (Bilgiç et al, 2018). The study did not examine other members of the LGBTIQA+ population and only discussed those representing themselves as lesbian or gay, as this tool had been developed in 1988. A more extensive quantitative study, performed in Israeli women's healthcare centres by Tzur-Peled et al (2021), used a cross-sectional design administering self-report questionnaires to 184 nurses. It was noted that Israeli’ nurses' knowledge was low, and that they had a negative view of lesbianism. Additionally, they found a significant association between age, education, residence, seniority and professional status and attitudes to treatment of lesbians (Tzur-Peled et al, 2021). It is important to note that this study, like Bilgiç et al (2017), did not include the full population of people who identify as LGBTIQA+, instead focusing on lesbians.

Prevailing literature suggests that maternity care is currently inadequate at meeting the needs of LGBTIQA+ people (Roosevelt et al, 2021). Some of the literature has identified transphobic behaviours by maternity care providers (Hoffkling et al, 2017; Malmquist et al, 2019). Tollemache et al (2021) audited 19 medical students concerning ‘Rainbow Healthcare’, a programme that supports LGBTIQA+ community (Carman et al, 2020). The authors identified that UK students needed more understanding when answering questions concerning maternity and childbirth. This reinforces that education for healthcare professionals is vital to address health inequities that gender-diverse people experience. However, what does this look like if the opinions of maternity-specific healthcare professionals still need to be represented or investigated?

Pezaro et al (2023) conducted a study on perinatal care for trans and non-binary people in the UK, where maternity care is delivered primarily by midwives as autonomous practitioners. The researchers used an interpretive framework of constructivism and a pragmatic theory that supported their mixed-methods approach, enabling detailed exploration of complex phenomena. Midwives' attitudes were found to be highly positive to trans and non-binary people (Pezaro et al, 2023). However, their findings also stated that a heteronormative care model showed oppressive outcomes for the trans and non-binary population.

Dolan et al (2020) recommended that healthcare professionals should have access to relevant evidence-based guidelines, and informs future research and partnerships with those from the LGBTIQA+ community. Pellicane and Ciesla (2022) suggested that that trans and non-binary people may need additional protection, given they experience disproportionate rates of victimisation and depression compared to their cisgender peers. This is from a suggestion that some childbearing women may find sharing a ward with trans men disconcerting (Pellicane and Ciesla, 2022), leading to further questions of providing a safe environment for all, and not changing the environment for solely the trans and non-binary community.

Social media and language

Social media has manipulated language and shapes how people communicate online. Social media use has been magnified because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Li et al, 2020). It is apparent in the literature that people of childbearing age engage with social media frequently (Chee et al, 2023). Women and the gender-diverse community experience gender discrimination within social media discourses and are under-represented in public health debates (Mishori et al, 2019). For example, a review by Zhu et al (2019) identified 6442 speakers and co-authors of research presented at the Academy Health's Annual Research Meeting in 2018, and reported that male researchers had momentous influence in social media platforms compared to their female peers.

The efficient use of social media has become a priority for studying health-related behaviours through a gendered lens; therefore, healthcare and social media research has concentrated on studying how gender stereotypes are presented in health-related content. For example, a study by LeBeau et al (2020) investigated how health-related content was shared on social media platforms. The study concluded that content shared on social media is fundamental, especially when considering the repercussions that content may have for behaviour; in particular, social media platforms tended to promote gender stereotypes and norms for health and sexual health (LeBeau et al, 2020).

Conclusions

Midwifery remains a profession marginalised in broader healthcare systems worldwide that continue to advantage biomedically governed pregnancy. This narrative literature review emphasises that the available literature is chiefly from the point of view of the service user, the LGTBIQA+ population who have accessed maternity and childcare services. Not all literature available was from maternity specifically, but also involved childcare centres. Nevertheless, this valuable literature provides insight into how to improve maternity services and considers many types of people who access maternity services. It is recommended that education is provided for healthcare professionals when working with LGBTIQA+ people; updating paperwork and policies at a structural level will have a vast impact holistically.

However, it is evident that further research is needed from healthcare providers' and maternity professionals' perspectives. Maternity services may differ not only in geographical location, but also in model of care. Researchers should direct their efforts to identifying the attitudes and perceptions of maternity-specific healthcare professionals. Supporting midwives, the history of feminist midwifery and its work in ensuring equality for women's rights is essential to ensure all angles and considerations have been performed to provide a well-rounded and genuinely all-inclusive environment. Challenges such as communication, professional embarrassment around a topic, anxiety about using the wrong terminology or unintentionally asking intrusive, inappropriate questions need to be explored.

Key points

- This literature review explored the use of gender neutral language in maternity services, highlighting the LGBTIQA+ perspective, but also a lack of research into healthcare professionals' views on its use

- Valuable suggestions from the LGBTIQA+ community highlighted that further education for staff members is required alongside a structural level change of paperwork, such as in birth certificates

- Further research is needed to identify the needs of midwives, with the aim to promote confidence, provide support to midwives and enable them to fulfil their full scope of practice when providing care.

- Etymology is important to consider when investigating and adapting language, as not only does it provide historical importance, but promotes understanding and interconnects language and culture.

CPD reflective questions

- What do you know about gender neutral language?

- What do you know about non-binary people?

- What do you think of replacing words such as ‘mother’ with gender neutral terminology? Do you think an additive approach is better?

- What do you think of the term ‘chestfeeding’ instead of ‘breastfeeding’?

- What do you think of the term ‘non-birthing parent’?