As a result of the benefits of human milk, breastfeeding is advocated as the healthiest way to feed infants and has become one of the most effective universally promoted health measures for mothers and their infants (North et al, 2022). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2011; 2024) recommends that infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months postpartum and thereafter breastfed with complementary foods until 2 years of age or older to achieve optimal health, growth and development.

In children, breastfeeding protects against infections and malocclusion, is associated with increased intelligence quotient points and reduces the risk of being overweight and developing diabetes (Victora et al, 2016). Continuing breastfeeding after 6 months reduces the risk of various infections and helps decrease rates of food intolerance in children (Wray and Garside, 2018). Women who breastfeed have reduced risk of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, as well as ovarian and breast cancer (Fisk et al, 2011;Victora et al, 2016; Neves et al, 2021).

It is estimated that inadequate breastfeeding is responsible for 16% of child deaths each year (Victora et al, 2016; WHO, 2020). Victora et al (2016) estimated that the promotion of breastfeeding at a universal level could prevent up to 823000 deaths in children under 5 years old and 20000 deaths from breast cancer annually. These and other projected benefits of breastfeeding have driven governmental and national agencies to follow the WHO's (2024) recommendation that children initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth, be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months and begin complementary feeding from 6 months until 2 years or beyond.

Despite these recommendations, global breastfeeding rates continue to fall short of the desired targets. According to the WHO's (2022) global breastfeeding scorecard, 48% of infants were exclusively breastfed between 2015 and 2021, a 10% increase from the previous decade. Although this still falls significantly short of the 2030 target of 70%, it is reassuringly close to the World Health Assembly's target of 50% by 2025 (WHO, 2014a). The scorecard also revealed that 70% of breastfeeding mothers continued breastfeeding for 12 months and that only 45% breastfed for up to 2 years, as opposed to the 2030 targets of 80% and 60% respectively (WHO, 2022). The encouraging progress made in global breastfeeding rates over the past decade should further persuade individual nations to intensify their efforts to support continued breastfeeding to meet the 2030 targets.

To understand which aspects of existing support need strengthening and the type of novel support required, a regularly updated understanding of breastfeeding‑associated factors is important (Chambers et al, 2007). With studies estimating as high as 60–80% of breastfeeding mothers who discontinue breastfeeding doing so earlier than desired (Odom et al, 2013; Unicef, 2017), it is necessary to explore mothers’ breastfeeding experiences and identify factors that will improve targeted intervention strategies. This scoping review aimed to provide insight into the reasons behind mothers’ decisions to cease breastfeeding or switch to mixed feeding in the first 6 months postpartum.

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed, Ovid maternal and infant care and global health electronic databases was conducted using PRISMA guidelines (Page et al, 2021).

Search strategy

Appropriate search terms were identified using the population, intervention, control and outcomes tool. Extensive search string combinations were developed using Boolean operators and truncation to maximise search results. The retrieval strategy on all databases was: ((‘breastfeeding’ OR ‘exclusive breastfeeding’) AND (‘cessation’ OR ‘stopping’ OR ‘problems’ OR ‘challenges’ OR ‘barriers’ OR ‘experience’.

As the global nutrition targets were passed by the World Health Assembly in May 2012 (WHO, 2014b), only studies published from 2013 onwards were included. Identified databases were searched in April 2023. Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Parameter | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Language | English | Languages other than English |

| Year of publication | From 2013 onwards | Before 2013 |

| Study design | Primary research Quantitative and qualitative studies Cross-sectional studies Observational studies | Literature/systematic review Articles |

| Study participants | Mothers with a history of breastfeeding following a vaginal birth | Mothers who had caesarean section or other special circumstances (including extreme age and settings) All other participants |

Screening

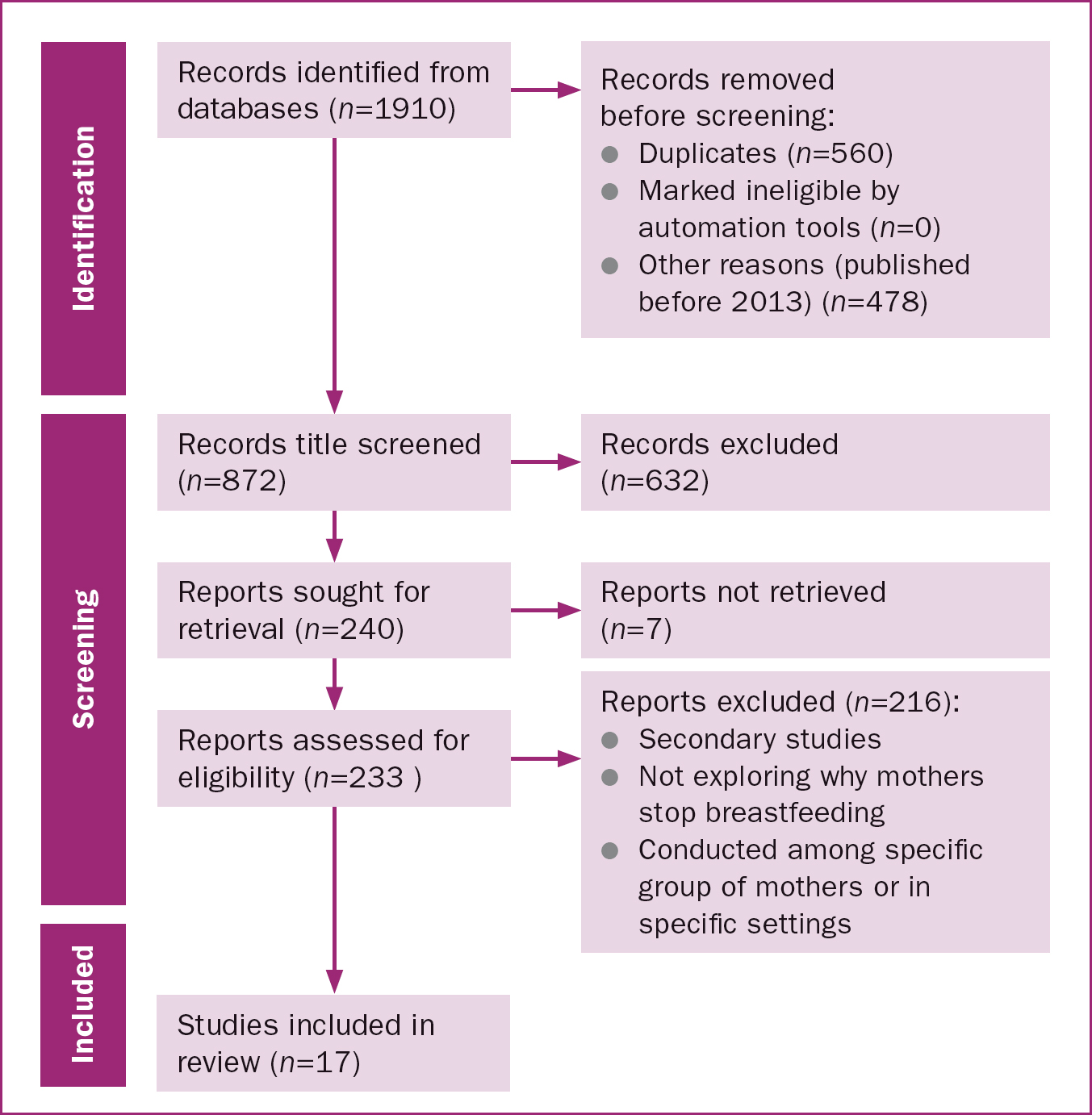

A total of 1910 studies were retrieved from PubMed and Ovid. Duplicates (n=560) and studies published before 2013 (n=478) were excluded, leaving 872 studies. Screening study titles resulted in the removal of a further 632 studies. Figure 1 outlines the search and screening process.

Study eligibility

Of the 240 studies included in the final round of screening, 233 were available for full‑text review, 17 of which met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. As this was a scoping review, no quality assessment was performed.

Analysis

The extracted data from the included studies describing the challenges hindering the continuation of exclusive breastfeeding were analysed using Braun and Clarke's (2008) thematic approach.

Results

Table 2 summarises the 17 included studies, which were conducted in 14 countries across five continents. The studies used different methodologies, including interviews, observational analyses, mixed methods and qualitative exploratory approaches. Relevant data on why mothers chose not to continue exclusive breastfeeding were extracted. Mothers were reported to either switch to mixed feeding or discontinue breastfeeding entirely.

| Reference | Objectives | Design and sample size | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wagner et al, 2013 | To characterise breastfeeding concerns from open-text responses and determine association with cessation of breastfeeding by 60 days and feeding formula between 30 and 60 days | Interviews, 532 participants | USA |

| Gianni et al, 2019 | To investigate breastfeeding difficulties in first months after birth and association with early breastfeeding discontinuation | Observational, 792 participants | Italy |

| Norman et al, 2022 | To investigate factors that influence breastfeeding behaviour and understand healthcare professionals’ role in promoting and facilitating breastfeeding | Mixed methods, 1505 participants | UK |

| Hendaus et al, 2018 | To outline breastfeeding barriers | Cross-sectional, 453 participants | Qatar |

| Diji et al, 2016 | To assess challenges and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers attending child welfare clinic at regional hospital | Cross-sectional, 240 participants | Ghana |

| Shi et al, 2021 | To examine determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in first 6 months of infancy | Cross-sectional, 5237 participants | China |

| Feenstra et al, 2018 | To explore mothers’ perspectives on when breastfeeding problems were most challenging and prominent in early postnatal period, and identify possible factors associated with breastfeeding problems | Mixed methods, 1437 participants | Denmark |

| Chang et al, 2019 | To investigate factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding cessation at 1 and 2 months postpartum | Postpartum survey, 1077 participants | Taiwan |

| Al Shahrani et al, 2021 | To assess exclusive breastfeeding rates and identify risk factors for early breastfeeding cessation at maternal and institutional levels | Observational, 136 participants | Saudi Arabia |

| Tarrant et al, 2014 | To explore experiences of mothers who prematurely discontinued breastfeeding and identify contributing factors that might help women breastfeed longer | Qualitative exploratory 24 participants | Hong Kong |

| Brown et al, 2014 | To explore reasons why women stop breastfeeding completely before their infants are 6 months old and identify factors associated with cessation and timing of cessation | Qualitative exploratory 500 participants | Canada |

| Schafer et al, 2019 | To understand gap between breastfeeding initiation and duration through in-depth exploration of first-time mothers’ breastfeeding experiences | Interview, 82 participants | USA |

| Tampah-Naah et al, 2019 | To explore challenges to breastfeeding practices by considering spatial, societal and maternal characteristics | Qualitative exploratory 20 participants | Ghana |

| Khan and Kabir, 2021 | To understand factors that affect exclusive breastfeeing practice in Noakhali district | Mixed method, 220 participants | Bangladesh |

| Ratnayake and Rowel, 2018 | To assess prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and barriers for continuation up to 6 months in Kandy District | Cross sectional, 354 participants | Sri Lanka |

| Moss et al, 2021 | To describe demographic profiles of participants reporting different feeding practices and reasons for not exclusively breastfeeding to 6 months | Cross-sectional retrospective, 2888 participants | Australia |

| Sun et al, 2017 | To investigate reasons why mothers in mainland China stop breastfeeding before infants were 6 months old | Interview, 562 participants | China |

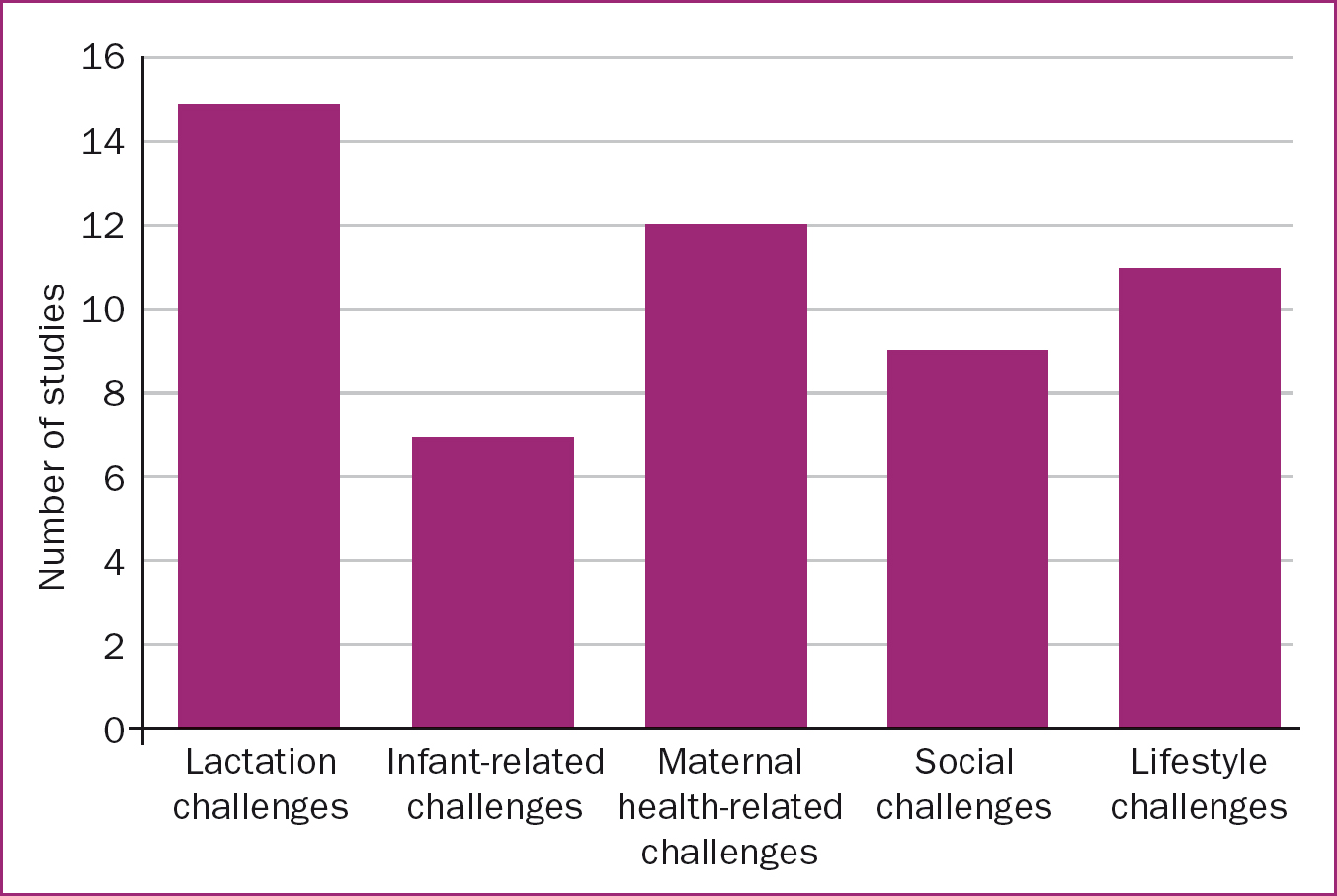

Five broad themes were identified, describing challenges with lactation, the infant, maternal health, social situations and lifestyle, as shown in Table 3. All studies reported challenges across more than one theme, with lactation‑ and infant‑related challenges being most and least frequently reported respectively (Figure 2).

| Theme | Associated factors |

|---|---|

| Lactation-related challenges |

|

| Infant-related challenges |

|

| Maternal-related challenges |

|

| Social challenges |

|

| Lifestyle challenges |

|

Lactation-related challenges

Of the 17 studies, 15 reported lactation‑related factors for early exclusive breastfeeding cessation. These included nipple injuries, breast pain, engorgement, breast swelling, perception of insufficient breast milk, nipple thrush, mastitis and breast abscess.

Although all studies reported more than one factor, perception of insufficient breast milk supply or feeling that the baby did not get enough milk was the most common lactation‑related issue given for breastfeeding cessation, reported in 11 of the 17 studies. An interview‑based study of 82 breastfeeding mothers in the USA found that the perception of insufficient breast milk production was associated with discontinuing breastfeeding in the early stages (Schafer et al, 2019). Similarly, an observational study with 136 breastfeeding mothers found that 37% of mothers stopped breastfeeding in the first 2 months (Al Shahrani et al, 2021). A mixed‑methods study among 220 mothers by Khan and Kabir (2021) found that 54% of those who had stopped breastfeeding gave inadequate breast milk supply as the primary reason.

However, a cross‑sectional study of 354 mothers in Sri Lanka by Ratnayake and Rowel (2018) reported that despite 99% of the participants being aware of exclusive breastfeeding practices, the main reason for early cessation was the mother believing that breast milk alone was not enough for the baby (53%). Breast milk alternatives reportedly given to babies in the first 6 months were water (91%), fruit juices (84%), mashed rice (71%) and formula milk (16%) (Ratnayake and Rowel, 2018).

Poor latch and breastfeeding skills were the second most common lactation‑related factor for discontinuing breastfeeding (Tarrant et al, 2014; Moss et al, 2021). Participants in a qualitative study felt that antenatal classes primarily focused on the advantages of breastfeeding but offered very little about the actual breastfeeding experience and expectations (Tarrant et al, 2014).

Breastfeeding‑related nipple pain and injuries were top reasons given in studies by Gianni et al (2019), Norman et al (2022) and Chang et al (2019). These studies were conducted in Italy, the UK and Taiwan respectively, with sample sizes ranging between 792 and 1505 participants. An exploratory study of 532 breastfeeding mothers found that feeding difficulty was the most common reason for cessation in the first week, while breastfeeding‑related nipple pain was the most common reason for discontinuing between 7 and 60 days (Wagner et al, 2013). Other studies identified thrush, mastitis and breast abscess as reasons for cessation (Wagner et al, 2013; Sun et al, 2017; Gianni et al, 2019; Moss et al, 2021; Norman et al, 2022).

Infant-related challenges

Infant‑related factors were quite diverse and included illness (Shi et al, 2021), tongue tie or inability to latch properly (Feenstra et al, 2018; Norman et al, 2022), refusal to feed (Wagner et al, 2013; Shi et al, 2021) or showing interest in regular food (Moss et al, 2021), failure to thrive on breast milk (Norman et al, 2022), being intolerant to breast milk (Hendaus et al, 2018) and biting (Wagner et al, 2013; Moss et al, 2021). Gianni et al (2019) found that 20% of mother who discontinued breastfeeding early did so on account of the failure of their infants to thrive. Khan and Kabir (2021) reported that although 308 of their 1505 respondents stopped breastfeeding because of tongue tie, failure to thrive was the second most common infant‑related reason for cessation.

Maternal health-related challenges

There were three key subthemes relating to how maternal health challenges led to changes in breastfeeding practice or breastfeeding cessation: maternal illness, including mental health or prescribed medication, fatigue and stress, and sleep deprivation. Norman et al (2022) found that 46.7% of respondents in the UK identified a change in their mental health while breastfeeding. Many (22%) reported feeling depressed, 10% felt guilty and 8% expressed anxiety. Of all mothers who experienced mental health issues associated with breastfeeding, 42.7% reported sleep deprivation (Norman et al, 2022).

A cross‑sectional study of 5237 breastfeeding mothers in China reported that 16% of mothers who stopped breastfeeding within 6 months cited maternal illness as the primary reason (Shi et al, 2021). Another cross‑sectional study of 2888 breastfeeding mothers in Australia reported that maternal health‑related factors made up 11% of reasons for ceasing breastfeeding before 6 months (Moss et al, 2021). An interview‑based study in China (Sun et al, 2017) found that medical factors (31%) in either the infant or mother was the second most common reason for discontinuing breastfeeding within the first 6 months postpartum. The reported maternal medical factors included mastitis, fever, wound infections and other illnesses. Maternal health conditions or prescribed medications were also highlighted as reasons for discontinuing breastfeeding earlier than desired by Al Shahrani et al (2021), Chang et al (2019), Gianni et al (2019) and Wagner et al (2013).

Gianni et al (2019) found that maternal fatigue was the third most common reason (30%) mothers gave for discontinuing breastfeeding, after cracked nipples (41%) and perception of insufficient breast milk (36%). A qualitative exploratory study among 500 breastfeeding mothers in Canada reported that the most frequent reason cited for early cessation of breastfeeding was ‘inconvenience/fatigue due to breastfeeding’ (23%) (Brown et al, 2014). This related to mothers perceiving breastfeeding as being tiring or demanding, as well as lacking sufficient time for breastfeeding while caring for other children. Al Shahrani et al (2021) also found that maternal fatigue (12%) followed insufficient or a lack of breastmilk (37% and 51%, respectively) as the third most common reason for stopping breastfeeding in the first 2 months postpartum. The study found that maternal fatigue was mostly reported at 6–8 weeks after birth.

Social challenges

The decision to discontinue breastfeeding and social and family influences on breastfeeding practices were the most reported social reasons why mothers stopped breastfeeding. Ratnayake and Rowel (2018) found that 51% of participants were advised by family members to cease breastfeeding early. Encouragement for early cessation mostly came from mothers‑in‑law (56%) or mothers (44%), with 29% reporting that their husband also influenced their decision. Another cross‑sectional study of 240 mothers in Ghana by Diji et al (2016) found that nursing mothers were culturally pressured to give water and artificial feeds to infants. This was the third most constraining factor to exclusive breastfeeding, following feelings of insufficient breast milk and short maternity leave. Tampah‑Naah et al (2019) identified close associates such as grandmothers, co‑tenants and other relatives as people who influenced and sometimes challenged mothers on exclusive breastfeeding in Ghana. The authors argued that relatives, particularly grandmothers, were sometimes so influential that they intentionally gave babies water, often against the will of the mothers, disrupting exclusive breastfeeding.

Chang et al (2019) showed that maternal choice, without further explanation, was the third most common reason (7%) for breastfeeding cessation in the first month postpartum and the second most common (9%) in the second month. Poor understanding of breastfeeding, likely as a result of deficient or inconsistent health education, was reported by Hendaus et al (2018) and Ratnayake and Rowell (2018). The latter study found that the main reason for early cessation of exclusive breastfeeding was the mother thinking that breast milk alone was not enough for the baby (53%). Around 68% of the respondents knew that breast milk could be expressed and stored, of which 65%, 48% and 12% knew it could be stored at room temperature, in a refrigerator and freezer respectively (Ratnayake and Rowel, 2018).

Poor breastfeeding support or signposting to support were highlighted by Tarrant et al (2014) and Gianni et al (2019). An exploratory study of the experiences of mothers who discontinued breastfeeding prematurely in Hong Kong found that many of the mothers reported feeling abandoned to figure out how to breastfeed on their own because midwives in public hospitals were too busy to provide direct support (Tarrant et al, 2014). Gianni et al (2019) found that 63% of participants experienced some form of breastfeeding difficulties in the first month, 9% in the second and 10% in the third month postpartum. Of these, 49% reported being supported by healthcare professionals, 20% addressed the issues on their own and 20% reported that the issues were never resolved. Of those whose issues remained unresolved, only 7% continued breastfeeding.

Lifestyle challenges

Returning to work was the main lifestyle‑related factor for ceasing breastfeeding entirely. Sun et al (2017) found that returning to work was cited by 12% of mothers who stopped breastfeeding within 1 month, 38% of those who stopped at 2–4 months and 48% of those who stopped at 5–6 months. Gianni et al (2019) reported that 4% of early cessation was because the mothers returned to work. Brown et al (2014) found that in Canada, return to work was cited as the primary reason for stopping breastfeeding by 8% of mothers who stopped in the first week, 11% of those who stopped at 1–6 weeks and 20% of those who stopped after 6 weeks. The study also found that mothers whose infants were 6 weeks or older were more likely to cite ‘return to work/school’ as their reason for breastfeeding cessation. Chang et al (2019) reported that 4% of mothers who stopped breastfeeding in the second month did so as a result of returning to work/school. They also found that only a third of breastfeeding mothers who returned to work continued to breastfeed beyond 2 weeks after resumption. Given that official maternity leave in Taiwan is only 8 weeks, the authors suggested consideration of lactation programmes with flexible work schedules as ways to improve breastfeeding duration (Chang et al, 2019).

Ratnayake and Rowel (2018) reported that 91% of participants who returned to work in the first 6 months did not practice expressing breast milk and therefore could not maintain exclusive breastfeeding. These mothers reported that their superiors and colleagues had neutral or discouraging attitudes towards expressing at the workplace. One of the participants stated that the presence of closed‑circuit television at work discouraged her from expressing, while another said she had to go to the toilet to express milk. The authors argued that a revision of the legislation was necessary to address the significantly shorter maternity leave allowed in the private sector. An exploratory study of 20 breastfeeding mothers in Ghana (Tampah‑Naah et al, 2019) found that work schedules often interfered with breastfeeding practices, as mothers were not typically allowed to take babies to work and crèches were often situated away from mothers’ places of work. They highlighted that most workplaces in Ghana do not have breastfeeding cubicles or rooms, as required by law.

Shi et al (2021) found that returning to work/school was the fourth most frequent reason for early breastfeeding cessation (7)%. Employed mothers who received relatively longer paid leave were more likely to exclusively breastfeed, indicating the opportunity cost of exclusive breastfeeding for mothers and the choice between working for money and continuing to exclusively breastfeed (Shi et al, 2021). A cross‑sectional study of 453 mothers in Qatar found return to work (16.3%) was the third most common barrier to breastfeeding (Hendaus et al, 2018). The authors suggested that despite the International Labor Organization support for maternity leave and family‑friendly strategies, the campaign, legislations supporting maternity rights and protections for women have not always been robust in the developing world.

Discussion

Studies have identified factors that may precipitate early cessation of breastfeeding, including mothers’ intention not to continue (de Jager et al, 2013; Sun et al, 2017). While this is often true, a clear understanding of why mothers choose to switch from exclusive breastfeeding to mixed feeding, or discontinue breastfeeding early (in the first 6 months) should form the bedrock of breastfeeding intervention strategies. Studies have shown that clinical supports are insufficient in helping mothers meet their breastfeeding goals, in line with the WHO targets (Odom et al, 2013). This study identified five themes, centring on challenges related to lactation, the infant, maternal health, social experiences and lifestyle.

Despite being conducted across 14 different countries, including the USA, China, Australia, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Ghana, Canada, Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, Denmark, Qatar, the UK and Italy, the 17 included studies reported common factors influencing mothers’ decisions to discontinue exclusive breastfeeding. Although the authors acknowledge that these countries are at varying stages of reaching breastfeeding targets and each faces unique issues, this shows that the overall picture of the challenges encountered by breastfeeding mothers is largely comparable globally.

Lactation

Lactation‑related reasons were the most frequently reported for early cessation. This is similar to Li et al's (2008) findings in an infant feeding study, which reported that lactational and nutritional reasons were most influential in the decision to stop breastfeeding in the first month. Within this topic, feelings of insufficient breast milk production and that the baby was not getting enough breast milk (33%) were most commonly reported. This is consistent with studies that have suggested that mothers who are not confident that their infants are getting enough breast milk are likely to stop breastfeeding early (Li et al, 2008; Huang et al, 2009; Atchan et al, 2011; Gökçeoğlu and Küçükoğlu, 2017; Widaryanti et al, 2022).

Factors influencing the feeling of insufficient breastfeeding are multifaceted, and breastfeeding self‑efficacy is a major factor. Generally, mothers with high efficacy will believe they are able to make sufficient milk for their babies’ needs (Huang et al, 2022). However, perception of insufficient milk supply has been argued to be subjective, rather than a clinical conclusion, and mothers’ concerns about breast milk supply are believed to begin even before commencement of breastfeeding and are precipitated by infant behaviours such as crying and suckling (Peacock‑Chambers et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2022). More than 95% of mothers are able to produce adequate milk to meet the nutritional requirement of their babies in the first 4 months (Brown et al, 2014). Better understanding of the breastfeeding process and normative behaviour of newborns may reduce the incidence of perceptions of inadequate supply (DaMota et al, 2012; Quinn et al, 2023).

Quinn et al (2023) carried out an online survey of 805 lactating mothers, aimed at understanding the influence of expressed breast milk on perception of milk supply. They found that descriptions of how participants felt about a potential increase, decrease or no change in their supply elicited a range of responses, some of which were unexpected. Some participants’ preconceived reactions about their breast milk supply did not change when they discovered that they produced more, less or the same volume of milk as they assumed they produce. Studies have attributed perception of insufficient breast milk supply, along with anxiety, to be closely related to mothers’ psychology (Walker, 2004; Atchan et al, 2011), influenced by personal experiences, such as caesarean section or traumatic births, delayed breastfeeding initiation and ineffective infant suckling (Huang et al, 2022).

Returning to work

Although data on breastfeeding prevalence after a return to work are generally scarce, return to work was the second most frequently reported reason for breastfeeding cessation or opting for mixed feeding. This is consistent with studies that associate return to work, particularly in the first 6 months, as a main reason for early breastfeeding cessation (Burns and Triandafilidis, 2019; Dutheil et al, 2021). Working conditions and flexibility (Lakati et al, 2002), along with heterogeneous external factors, may impact mothers’ ability to combine breastfeeding and work, including policies and work culture in specific regions of nations (Dutheil et al, 2021).

There are two main factors attributing return to work with breastfeeding cessation: returning too early and having an inconducive workplace and structure. The Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO, 2023) has estimated that over 500 million working women are not provided with essential maternity protections and that only 20% of countries require employers to provide paid breaks and facilities for breastfeeding or expressing breast milk. These factors force mothers to return to work too early and be away from their babies while they are at work.

A systematic review and meta‑analysis of breastfeeding prevalence after returning to work by Dutheil et al (2021) found that the intention to breastfeed was inversely associated with returning to work and the prevalence of breastfeeding after return to work was 25%. The authors reported that the general trends of the study findings were heterogeneity and lack of data. However, the results demonstrated a higher breastfeeding rate after returning to work in Asia than in Europe, and that the USA seemed to have a similar breastfeeding rate after return to work to Asia (Dutheil et al, 2021). The study also found that Middle Eastern countries have the lowest prevalence of breastfeeding after return to work, while data from Africa are unavailable (Dutheil et al, 2021).

As reported by Ratnayake and Rowel (2018), 91% of mothers who returned to work in the first 6 months did not express breast milk and therefore could not maintain exclusive breastfeeding. Tampah‑Naah et al (2019), Abekah‑Nkrumah et al (2020) and Wolde et al (2021) also emphasise the role of an inconducive workplace and inadequate support at work in early cessation of breastfeeding. Studies have proposed that codesigning policies that describe the role of each actor (ie managers and co‑workers) in supporting breastfeeding in the workplace are feasible solutions to these challenges (Pérez‑Escamilla et al, 2023). With such poor data, growing campaigns to curb these challenges are important, particularly during world breastfeeding week in 2023, which was themed ‘let's make breastfeeding and work, work’ (PAHO, 2023).

Inconvenience and fatigue

The inconvenience associated with breastfeeding was another lifestyle related reason for breastfeeding cessations. Brown et al (2014) reported that 23% of participants in Canada stated inconvenience was the primary reason for stopping breastfeeding. This is similar to the findings of cross‑sectional study conducted 7 years later in Australia by Moss et al (2021), which found that 16% of respondents listed inconvenience as the primary reason for discontinuing breastfeeding. Breastfeeding is often more challenging than mothers expect it to be (Elder et al, 2022), with over 60% of mothers estimated to have breastfeeding difficulties in the first month postpartum (Gianni et al, 2019). The challenges are even more pronounced in mothers who expect breastfeeding to be a smooth process with only positives, compelling healthcare professionals to offer honest and realistic information on breastfeeding expectations (Powell et al, 2014). This further underlines the need to have open and honest discussions on breastfeeding with mothers, to empower them to be better prepared for challenges and inconveniences commonly associated with the breastfeeding journey.

Postpartum fatigue has long been perceived as a common condition (Zhang et al, 2022). However, maternal fatigue made up 37% of maternal health reasons for breastfeeding cessation or change in practice identified in this review. This is consistent with Brown et al (2014), who found that fatigue/inconvenience were the most common reasons cited for early breastfeeding cessation. Despite an earlier study concluding that postpartum fatigue is not dependent on mothers’ infant feeding choice (Callahan et al, 2006), decisions to stop breastfeeding in response to fatigue could be a cry for help, especially as the occurrence of physical difficulties during breastfeeding has been associated with a higher risk of postpartum depression (Gianni et al, 2019).

Breastfeeding skills and knowledge

Inadequate breastfeeding skills and techniques are frequently reported primary reasons for discontinuing breastfeeding (Odom et al, 2013; Rollins et al, 2016; Colombo et al, 2018; Maharlouei et al, 2018). Inadequate techniques have also been implicated in other breastfeeding challenges, including nipple injuries, breastfeeding pain, engorgement and mastitis (Gianni et al, 2019). This suggests that effective breastfeeding support and education on techniques, latch and positioning would not only help prevent early cessation but also reduce the rate of complications.

It is crucial to ensure continuous comprehensive postpartum support. Effective, individualised antenatal education and postnatal support have been shown to increase exclusive breastfeeding rates and improve breastfeeding attitudes (Huang et al, 2019). The wide use of mobile devices has positioned mobile health as one of the most effective areas of healthcare transformation. Studies have explored the application of mobile technologies in improving breastfeeding rates and outcomes. A meta‑analysis by Qian et al (2021) found that interventions integrated into mobile health can improve exclusive breastfeeding rates and efficacy. Mother‑centred design and effective implementation of individualised breastfeeding support harnessing advancing digital health transformation will go a long way in improving breastfeeding outcomes and experiences for mother and baby.

Implications for practice

The present review's findings provide further insight into the reasons behind early breastfeeding cessation from the global perspective and an option for broad categorisation for targeted interventions. This highlights the importance of providing continued individualised support systems to overcome maternal breastfeeding difficulties from antenatal through to the postpartum period and on to a return to work.

Limitations

Although this review included studies from 14 countries across five continents, it may not fully capture the global diversity of breastfeeding experiences, particularly in under‑represented regions, such as developing countries or rural areas. The methodological heterogeneity of the included studies, ranging from qualitative interviews to large‑scale surveys, poses challenges for direct comparisons, as variations in sample sizes, data collection methods and analytical approaches may influence reported outcomes. Furthermore, the review is limited to studies published in English, potentially excluding important research from non‑English‑speaking regions.

Conclusions

The decision to stop exclusive breastfeeding early is the result of a wide range of factors in five main areas relating to lactation, the infant, maternal health, social experiences and lifestyle. Although different nations are at different stages of meeting breastfeeding targets and often take differing approaches, a lack of adequate support largely underpins mothers’ decisions to discontinue breastfeeding earlier than desired. Honest information on breastfeeding and its common challenges, and timely and efficient support from healthcare professionals, family and peers are essential throughout the postpartum period.