Vaginal examinations are the most common intervention in labour (Pickles and Herring, 2020), and are historically embedded in maternity care (Downe et al, 2013; Shepherd and Cheyne, 2013; Shabot, 2021). Developed as a quantifiable measure for use in the 1950s alongside a partogram (Friedman, 1956), vaginal examinations are now used routinely by midwives and obstetricians to assess labour progression. They can also be used to confirm commencement of active labour, providing information on cervical dilation, effacement and position and descent of the presenting part of the fetus in the maternal pelvis (Downe et al, 2013; Moncrieff et al, 2022).

Global and national guidance currently recommends offering vaginal examinations at 4-hourly intervals in the active first stage of labour (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017; World Health Organization, 2021). However, this is based on limited and dated evidence (Moncrieff et al, 2022). Additionally, overuse of vaginal examinations has been consistently reported (Naughton, 2019; Shabot, 2021; Miller et al, 2022). This may have both a psychological impact on maternal mental health, inhibiting hormones involved in physiological labour progression, and can lead to overdiagnosis of labour dystocia, a delay in the progress of labour (Çalik et al, 2018). This can contribute to a cascade of unnecessary interventions (Downe et al, 2013; Hazen, 2017), potentially resulting in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes (Çalik et al, 2018). Research does not highlight any conclusive improved birth outcomes as a result of vaginal examinations (Downe et al, 2013; Naughton, 2019; Moncrieff et al, 2022). However, as studies have yet to produce high-quality evidence to support another method of assessment of labour progression, there has been minimal change in recent years (Moncrieff et al, 2022).

Enabling women's informed consent, is a central role of the midwife (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018; Pickles and Herring, 2020). However, over two decades ago, research highlighted the phenomenon of healthcare professionals seeking acquiescence in place of consent when the vaginal examination was unwanted (Ying Lai and Levy 2002; Lewin et al, 2005). If performed without consent, vaginal examinations have been documented in reports on obstetric violence (Perrotte et al, 2020). The ‘#MeToo’ movement is a global campaign centralising empowerment of women and the rejection of sexual violence against females (O'Neil et al, 2018). It closely mirrors the abuse of power seen in unconsented vaginal examination's during childbirth (Hill, 2020). This highlights the societal and cultural relevance of current research in this area.

Despite recent prioritisation of women's rights, there has been minimal research into understanding women's experiences of vaginal examinations in labour (Downe et al, 2013; Shabot, 2021; Moncrieff et al, 2022). The aim of this literature review was to collate what is known about these experiences, raise awareness and identify any gaps in knowledge to prioritise future research or guide policy.

Methods

This systematic literature review was conducted with the aim of understanding women's experiences of vaginal examinations in labour. This approach was deemed appropriate as detailed reporting of the methods ensures high validity and replicability (Aveyard, 2019). Literature reviews play a fundamental role in synthesising research, identifying gaps in knowledge to facilitate future research and providing thematic development (Frederiksen and Phelps, 2017; Paul and Criado, 2020). The literature review was conducted following the steps outlined by Aveyard (2019).

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed, aided by the ‘PEO’ search strategy framework (Kahn, 2003), which identifies key concepts, focusing on population, exposure and outcome, as seen in Table 1. Relevant synonyms were considered, using medical and lay language to maximise retrieval of relevant literature (Bramer et al, 2018). Additionally, wildcards (#) and truncation (*) accounted for pluralisation and differing spellings (Davies, 2019). The Boolean operator ‘OR’ was inputted between synonyms; ‘AND’ was used to combine each PEO concept (Table 1).

| Search concepts | Search terms | Boolean operator | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Women in labour | Wom#n OR mother* OR primigravida* OR multipa* OR primipa* OR maternal OR intrapartum OR labo#r OR childbirth OR birth OR delivery | AND |

| Exposure | Vaginal examinations | Vaginal examination* OR vaginal assessment* OR cervical assessment* | AND |

| Outcome | Women's experience | Experience* OR perception* OR view* OR opinion* OR feeling* OR satisfaction OR attitude* | AND |

While the search was conducted to explore experiences, which were likely to elicit mainly qualitative or mixed-methods studies, quantitative studies were not excluded if they fit the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Research from the last 10 years was included to reflect the paradigm shift in women's empowerment following the global #MeToo movement in 2017 (O'Neil et al, 2018). The search was originally conducted in December 2022 and then repeated in December 2023 prior to publication, to ensure all relevant research was included. No papers were removed at the point of updating the search, to retain the knowledge gained from the initial search. Only papers considering women's experiences were included, because of the directional interest of the research question. No studies were excluded based on geographical location, as although women's experiences may vary because of cultural and societal differences (Çalik et al, 2018), it was thought important to include all experiences collectively. Additionally, papers that considered vaginal examination antenatally or postnatally were excluded, as this review focused on labour care.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Global studies | Duplicated papers |

| English language | Not available in the English language |

| Primary research: quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods | Other systematic reviews |

| Women's experiences | Research that only explores the experiences of partners or other healthcare professionals |

| Published from 2012 onwards | Published before 2012 |

| Vaginal examinations in labour or to confirm labour commencement | Vaginal examinations antenatally or postnatally |

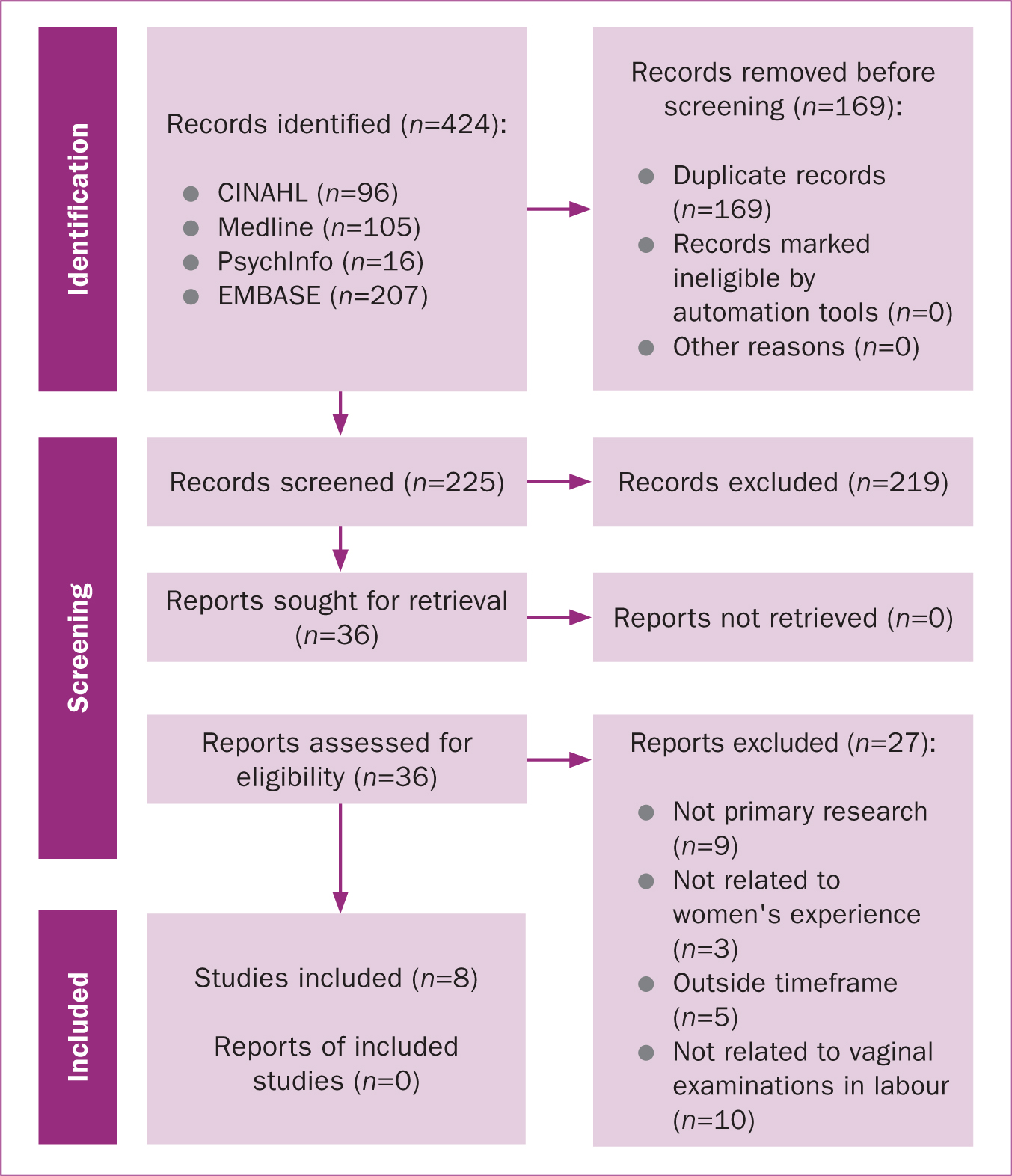

Four electronic databases were searched: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, PsychInfo and Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE). Four databases were deemed suitable to acquire sufficient breadth of relevant primary research (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2020). The databases used also needed to be available to the author through the university library. Medline and CINAHL were selected for their large volume of medical- and life science-based research (Bramer et al, 2018; Davies, 2019). EMBASE was used because of its biomedical standing (Davies, 2019), while PsychInfo provided a social science perspective on women's experiences, potentially revealing a deeper understanding of the topic (Frederiksen and Phelps, 2017). The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis diagram was used to direct and present the identification, screening and selection of papers (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

The studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018; 2020) tools for qualitative and randomised controlled trial designs and the British Medical Journal (2023) critical appraisal checklist for surveys, which was adapted for the four cross-sectional surveys (Cavaleri et al, 2018). Appraisal tools are essential in literature reviews as they systematically determine rigour and risk of bias (Noyes et al, 2018) to ensure the highest quality evidence is used in guiding clinical practice (Cavaleri et al, 2018).

Overall, the majority of studies met most of the appraisal criteria and were considered mid-high quality (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018; 2020; BMJ, 2023). No studies were excluded on the basis of the quality appraisal, however the appraisal informed interpretation of the findings, where studies measured the highest quality were considered first and those of lower quality were given less priority in the discussion (Cavaleri et al, 2018). The results of the quality appraisal are shown in Table 3.

| Reference | Quality appraisal |

|---|---|

| Dabagh-Fekri et al (2020) | High quality. |

| Klerk et al (2018) | High quality. |

| Hassan et al (2012) | High quality. |

| Keedle et al (2022) | High quality. |

| Rodrigues et al (2022) | Mid quality. |

| Seval et al (2016) | Mid quality. |

| Teskereci et al (2020) | High quality. |

| Yildirim and Bilgin (2021) | Mid quality. |

Interpreting and synthesising findings

Data from the included studies were mainly qualitative, derived either from interviews or open-ended survey questions, with some quantitative data from closed survey questions and anxiety scales. Qualitative data were analysed first, generating initial codes inductively, before combining them into themes (Clarke and Braun, 2017). Related quantitative data that could explain or contradict the qualitative themes were coded and integrated to develop the themes further. This broadly followed Guest et al's (2012) explanatory sequential approach to integrating qualitative and quantitative data.

In total, 424 papers were retrieved and exported into EndNote, a reference management software. Following the removal of duplicates, 255 records remained. These were screened via title and abstract to determine relevance and a further 219 papers were excluded at this point, in line with the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 2). Following full-text review of 36 papers, eight were included in the final review.

Results

The studies included in this review were four cross-sectional surveys from Palestine, the Netherlands, Iran and Australia (Hassan et al, 2012; de Klerk et al, 2018; Dabagh-Fekri et al, 2020; Keedle et al, 2022), three qualitative studies, two from Turkey and one from Brazil (Teskereci et al, 2020; Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021; Rodrigues et al, 2022), and one randomised controlled trial from Turkey (Seval et al, 2016). The studies are summarised in Table 4.

| Reference | Methodology and aims | Design | Sample and setting | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabagh-Fekri et al (2020) | Quantitative cross-sectional study exploring Iranian women's perceptions of vaginal examinations during labour | Questionnaire (demographic and obstetric data). Experiences measured by 5-point Likert scale | 200 primiparous women in teaching hospital in Tehran, Iran | Two thirds (62.9%) reported negative perception of exams. Significant relationship between perception of exam and perceived duration (P=0.02). Comfort with examiner increased perception of exam (P=0.006). One-person increase in number of examiners decreased perception of exam by 0.81 (P=0.031) |

| de Klerk et al (2018) | Mixed-methods cross-sectional study investigating women's experience of vaginal examinations during labour | Online survey, closed and open-ended questions | 159 postnatal women in the Netherlands | Quantitative: 35.2% reported negative experience during labour, 41.7% examined more often in labour than advised by international guidelines (every 2–4 hours). Birthing at home had significantly less risk of negative experience compared to in hospital (odds ratio: 0.28; 95% confidence interval: 0.11–0.72; P=0.01). Number of exams during labour increased odds of negative experience (odds ratio: 1.3; 95% confidence interval: 1.1–1.5; P<0.01). |

| Hassan et al (2012) | Mixed-methods cross-sectional study exploring women's feelings and experiences of vaginal examinations during childbirth | Semi-structured questionnaire delivered via face-to-face interviews | 176 postnatal women in Palestinian public hospital | Quantitative: 36% received ‘potentially high’ number of exams during intrapartum care, 41% reported being examined by high number of providers. Exams significantly higher in primiparous than multiparous (P=0.037), 82% reported pain during exam. |

| Keedle et al (2022) | Mixed-methods cross-sectional study exploring prevalence and experiences of obstetric violence by women who had a baby in past 5 years | Australian Birth experience study: national survey | 8546 women who responded to obstetric violence question and 626 women who provided qualitative response in Australia | Quantitative: demographic trends to higher rates of obstetric violence; younger age range (6% vs 3%), lower income, lower education (13% vs 10%), Aboriginal heritage (3% vs 1%), 48% responded ‘yes/maybe’ to question. Qualitative: Dehumanisation, powerlessness and violation. Exams second biggest subcategory considering obstetric violence. Negative experiences associated with poor rapport, consent and additional procedures not consented to (sweeping/artificial rupture of membranes). Women given multiple exams by different professionals, which negatively impacted the experience. Healthcare professional did not document extra procedures in notes |

| Rodrigues et al (2022) | Qualitative study that aimed to understand women's perceptions regarding care received during labour and birth | Semi-structured interviews in private room in hospital. Descriptive exploratory approach | 54 women recruited postnatally in hospitals in Rio De Janeiro | Obstetric interventions in birth: a counterpoint to scientific evidence. Humanisation as a necessity in the daily routine of obstetric care in women's voices. Vaginal examination perceived by women as disrespectful intervention if received without dialog and empathy |

| Seval et al (2016) | Quantitative study investigating association between digital vaginal examination during labour and psychological distress and pain compared to transperineal ultrasound assessment | Randomised control trial. Single blinded | 90 multiparous women recruited antenatally in a hospital in Turkey | Pre-admission anxiety levels similar between groups (P=0.93 vs P=0.65). Pain perception reduced during latent (P<0.01) and active (P=0.03) stages of labour and in postpartum period (P=0.02) for transperineal ultrasound group (statistical significance only found in latent phase). Anxiety levels similar between groups |

| Teskereci et al (2020) | Qualitative study exploring women's experiences regarding vaginal examinations during labour | In depth, semi-structured interviews. Hermeneutic–phenomenological approach | 14 women <24 hours postpartum in public hospital in Turkey | Hard to explain, necessary despite everything, facilitators, barriers, which one: professionalism or gender and humane approach. Pain, aches, embarrassment, fear and anxiety all expressed during exams. Felt exams were necessary in labour but performed too frequently. Women expressed importance of supportive approach by healthcare professional performing exam. |

| Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin (2021) | Qualitative study to determine experiences and factors related to vaginal examination during labour | Semi-structured interview and observation of women's behaviour during interview | 20 women recruited before discharge in two public hospitals in Turkey | Meaning of vaginal examinations, experience and emotional reactions, 8 participants felt lucky to experience same professional during exams, 12 described frequent exams as negative. Negative experiences associated with limited privacy. Shame, fear and embarrassment most common emotion during exams. Most women preferred female healthcare professional |

Four key themes were derived from the data: frequency of vaginal examinations, true, informed consent, emotional reactions and rapport building and humanisation.

Frequency of vaginal examinations

Women reported high frequency of examinations in all but the randomised controlled trial. High frequency was defined as a vaginal examination more than every 2 hours (de Klerk et al, 2018), over five vaginal examinations during labour (Dabagh-Fekri et al, 2020) or by self-reported excess of vaginal examinations by the women (Hassan et al, 2012; Keedle et al, 2022; Rodrigues et al, 2022). Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin (2021) highlighted that women reported vaginal examinations taking place as often as every 10–15 minutes. When describing the context in which their study was conducted, Hassan et al (2012) reported that midwives justified a high frequency of vaginal examinations in response to demand from women. However, only 3% of women who responded to the survey stated that this was true (Hassan et al, 2012).

Four studies suggested that women's experiences of vaginal examinations were influenced by how often they were performed (Hassan et al, 2012; de Klerk et al, 2018; Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021; Keedle et al, 2022). De Klerk et al (2018) found a significant correlation between the increased number of vaginal examinations and women interpretating negative experience, with the odds increasing by 31% for each vaginal examination. This exemplifies the importance of reducing unnecessary examinations. Women also perceived that vaginal examinations were often not recognised as an intervention by professionals and instead felt they were being used for educational purposes (Keedle et al, 2022).

True, informed consent

Vaginal examination without consent was a major theme in Keedle et al's (2022) research on obstetric violence during childbirth. Lack of discussion prior to the procedure, failure to stop the vaginal examination following withdrawal of consent and additional unconsented procedures performed, such as manual stetch of the cervix or artificial rupture of the membranes, were highlighted by women as causes to why true informed consent was not received (de Klerk et al, 2018; Keedle et al, 2022). One woman reflected on her experience in line with the ‘#MeToo’ movement, suggesting a cultural shift in women speaking out against sexual assault in childbirth (Keedle et al, 2022). Hassan et al (2012) also confirmed the inadequacy of prior information to achieve true informed consent. By surveying women's understanding as to the necessity of vaginal examinations, Hassan et al (2012) identified that the majority of women (95%) felt that it was required to ensure their baby's safety. This suggested misinformation, or at best misunderstanding, of the rationale for vaginal examinations in labour.

Additionally, de Klerk et al (2018) highlighted that women felt vaginal examinations were not presented as a choice. Keedle et al (2022) reported that women felt a pressure to conform through use of language and emotional blackmail.

Emotional reactions

Women consistently reported that vaginal examinations could be painful, distressing and invasive (Hassan et al, 2012; de Klerk et al, 2018; Dabagh-Fekri et al, 2020; Teskereci et al, 2020; Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021; Keedle et al, 2022; Rodrigues et al, 2022). The randomised controlled trial also found a non-significant trend towards higher levels of anxiety in participants in the vaginal examination trial arm, compared to the transperineal ultrasound arm (Seval et al, 2016). De Klerk et al (2018) found that women birthing at home reported a more positive perception of vaginal examinations.

Rapport building and humanisation

Another significant theme across five of the studies was humanisation (Hassan et al, 2012; Dabagh-Fekre et al, 2020; Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021; Keedle et al, 2022; Rodrigues et al, 2022). When women reported a good relationship with the professional administering the examination, their positive perception of the examination was increased (Dabagh-Fekri et al, 2020). This was supported by Yildirim and Bilgin (2021), where women who had one continuous healthcare provider throughout labour reported a more positive association with vaginal examination.

Hassan et al (2012), Keedle et al (2022) and Rodrigues et al (2022) suggested that negative experiences were associated with automated or impersonal approaches by the examiner. Word choice and use of language were contributary factors to negative perceptions. Additionally, some studies outlined that approach differed depending on the profession and gender of the attending clinician (Hassan et al, 2012; Teskereci et al, 2020; Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021). Women reported male physicians to be more insensitive (Hassan et al, 2012; Yildrim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021). The care provided combined obstetric and midwifery-led models in all but the randomised controlled trial, which was solely obstetric-led.

Discussion

This literature review aimed to understand women's experience of vaginal examinations in labour. Vaginal examinations played an integral part in positively or negatively influencing women's experiences of birth. More positive experiences were aligned with continuity of carer, birth at home and a compassionate approach by those delivering care. Lack of informed consent, an impersonal approach and frequency of examinations were associated with increased negative perceptions across women from a range of countries and cultures.

Guidelines in the UK recommend 4-hourly vaginal examinations in labour (NICE, 2017); however, this is based on one randomised controlled trial undertaken in 1996 (Abukhalil et al, 1996). This exemplifies the lack of research to justify offering routine examinations in labour. NICE (2014) recognised this, stating in their evidence summary that there is low-quality research to support the frequency of vaginal examinations in labour. Although they also endorse determining the necessity of vaginal examinations in conjunction with women's wishes, they continue to recommend routine vaginal examinations in clinical practice (NICE, 2017). This is important considering that if used in excess, vaginal examinations can disrupt physiological birth and potentially lead to maternal and neonatal complications (Naughton, 2019). Additionally, considering de Klerk et al's (2018) finding regarding the correlation between increased frequency of vaginal examinations and negative experiences, midwives have a responsibility to limit unnecessary vaginal examinations in labour (Shepherd and Cheyne, 2013). However, the present review and other literature indicate vaginal examinations are often used more frequently than the recommended guidelines (Downe et al, 2013; Moncrieff et al, 2022).

Using vaginal examinations as a teaching aid for junior doctors and student midwives has been theorised as a reason for excessive use of this intervention (Downe et al, 2013; Naughton, 2019; Nelson, 2021). However, there is limited evidence-based information to fully understand why vaginal examinations occur so frequently in clinical practice (Moncrieff et al, 2022). Home births have been suggested to reduce interventions (Hazen, 2017), a theory supported by de Klerk et al (2018). This may extend to a reduction in the frequency of vaginal examination in a home birth setting and explain why women birthing at home had a more positive perception of vaginal examinations in labour (de Klerk et al, 2018). This increased positivity could also be causal to continuity of carer (Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021), with fewer healthcare professionals being present at home births. This draws parallels to the plethora of research supporting midwifery-led continuity of care models (Sandall et al, 2016).

The gender and profession of the attending clinician affected women's experience of vaginal examinations, with more negative experiences aligned with male doctors performing the examination (Hassan et al, 2012; Teskereci et al, 2020; Yildirim and Çitak Bilgin, 2021). However, this was not a universal finding, which could suggest cultural or preferential differences between studies (Dabagh-Fekri et al, 2020), potentially limiting the transferability of findings across countries and cultures.

There is a concerning connection between vaginal examinations and lack of true informed consent. A non-consented vaginal examination is a major invasion of human rights (Vedam et al, 2017; Pickles and Herring, 2020) and can lead to significant physical and psychological trauma for women (Nelson, 2021; Shabot, 2021). Nelson (2021) described vaginal examinations as the ‘gatekeeper’ to accessing maternity care during COVID-19, because of the reformed admission policies. This exemplifies a power dynamic between healthcare professionals and birthing women and highlights the engrained and often unquestioned use of vaginal examinations in childbirth (Hassan et al, 2012; Shabot, 2021). The societal expectation to consent to medical practices is embedded in culture and the image of the ‘good girl’ ideal where women have to be ‘good’ and ‘submissive’ (Creech, 2019) reflects the passivity sometimes expected in regards to women consenting to vaginal examinations in labour. This can lead to coerced consent as a result of fear of opposing societal expectations (Nelson, 2021).

The importance of this research merges with the recent paradigm shift after women's protests against sexual violence, in the #MeToo movement (O'Neil et al, 2018). Women have begun to feel empowered to address deep-rooted issues surrounding vaginal examinations in maternity care, following this global campaign (Keedle et al, 2022). Where vaginal examinations were perhaps previously perceived by women as an unpleasant but necessary part of labour care (Hassan et al, 2012; Shabot, 2021), they are now being questioned on the harm caused if women are coerced or examinations are performed without consent (Hill, 2020; Nelson, 2021). This was mentioned in Keedle et al's (2022) survey, highlighting the significant cultural relevance of these findings and the importance of ensuring true, informed consent during vaginal examinations worldwide (United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, 2016).

Humanisation, defined as the behaviour and attitudes of healthcare professionals before and during examinations (Curtin et al, 2020), has potentially become more negative as a result of desensitisation to the invasiveness of a vaginal examination. Increasing work demands, prioritising efficiency over individualised care and the overmedicalisation of birth (Curtin et al, 2020; Nelson, 2021) are perhaps contributory factors to this. Ultimately, this has resulted in women feeling their choices are being neglected (Pickles and Herring, 2020; Nelson, 2021) and consequently impacting the autonomy that should be upheld for women during childbirth.

Implications for practice

The findings of this review indicate the need for further education for healthcare professionals about ongoing informed consent that is free from coercion, using appropriate communication, determining the necessary frequency of vaginal examinations and avoiding desensitisation (Curtin et al, 2020). Additional training on true informed consent and alternative or adjunct ways of assessing labour progression, such as maternal physical and behavioural cues (Shabot, 2021; Moncrieff et al, 2022), should be well-established in hospitals, to minimise vaginal examinations when not clinically indicated and stop any that are not consented to.

Future research

There is currently limited high-quality evidence supporting the use of examinations to benefit maternal and neonatal outcomes (Moncrieff et al, 2022). Future research should centre on the development of different methods of measuring labour progression, aiming to reduce or replace vaginal examinations with less invasive methods (Shabot, 2021). In addition, women's experiences should continue to be sought by qualitative means, to gain an in-depth understanding of whether newly acquired interventions and consent practices are meeting women's expectations for a positive and empowering birth experience. Future research should consider the relevance of geographical location and cultural differences on women's perceptions of vaginal examinations in labour, to support culturally relevant practice development and further inform the findings.

Strengths and limitations

This literature review effectively collates research and highlights the importance of further study in this area of maternity care. As this literature review was undertaken as part of an undergraduate midwifery degree, the data extraction and identification of themes was done by a single author, with support from a supervisor, because of the specific academic requirements. Implementing an additional author to identify and compare themes during the initial analysis phase could have increased the reliability and validity of the themes identified.

Conclusions

It is evident that global reform is needed with regard to vaginal examinations in labour, which, when performed in excess and without true informed consent, negatively impact women's labour experiences. Training to reinforce and update consent practices should be prioritised, as well as facilitating alternate measurements of labour progression. Barriers to implementing changes are likely, considering the widespread and historical use of vaginal examination in labour. However, continuing this research is essential, working in collaboration with women and healthcare professionals to maintain safety while preventing negative experiences and ending obstetric violence.