This May I should be celebrating my son's 7th birthday, however, sadly, I am grieving the 7 year anniversary of his death instead. It has been 3 years since I last wrote an article for British Journal of Midwifery to raise awareness of the virus and warn of its fatal risks (Craig, 2016). Much has changed since then, the biggest transformation being that I collated all of the work and resources I had created over the years into an official campaign name, What's In A Kiss? (WIAK).

Since 2012, I have had several impactful achievements with WIAK (Box 1). WIAK is the first UK campaign of its type that was established in conjunction with the NHS to highlight the importance of neonatal herpes among health professionals and the public. My campaign is run independently; I am not a charity because I still maintain a full time job in another industry.

In between these achievements, I have also worked with the Royal College of Midwifery (RCM), Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and a number of baby loss charities. I also conduct workshops at various London hospitals and deliver speeches for at the RCN and NHS Patient Safety Congress.

I am surprised at how far I have come, and how my determination to fight to raise the profile of neonatal herpes has evolved and developed over the years. I certainly didn't think, back when my journey started as a grieving mum, that I would have found the strength or the courage to have accomplished these milestones or be able to make a difference in the world. I have been incredibly fortunate along the way to have met so many wonderful, committed organisations, doctors, nurses and midwives all of whom have kindly supported me with their time and expertise.

Tay's story

For those of you who may not be familiar with my story, I want you to know why WIAK is so close to my heart. My son, Tay, was my first born and first true love of my life. His arrival was happily anticipated by our family and a significant turning point for me. I was a typical first time mum: I read and downloaded any baby-related information I could find, trying to protect my son from any potential danger—yet the biggest threat to his life, I had absolutely no knowledge of. Tay was born healthy, following a relatively normal labour. The day after his birth, we were allowed home. I was filled with excitement and nerves as I stumbled my way through dirty nappies and regular feeds. The joy quickly descended into darkness when, on day 3, I began to notice that he didn't seem to cry much and would sleep for hours on end, having to be woken for feeds or nappy changes. He had an irregular breathing pattern and I often found myself having to tap him gently when he was asleep, just to check he was still alive. I was reassured by friends, family and midwives that his silence was normal for newborns and that his lethargy was likely the result of jaundice. During my pregnancy, Tay had been a very active baby, so the changes in his movement were obvious. As much as I wanted to believe that he was content and relaxed, I couldn't ignore the uneasy feeling in the pit of my stomach and took him to A&E.

When I was asked what was wrong with him, I felt embarrassed to say it was because he didn't cry and slept most of the time. Surely most mums would be relieved to have a baby like this? I was assured that if there was anything seriously wrong with him, he would be screaming the place down. They couldn't have been more wrong. It is a common misconception that poorly babies tend to be irritable and cry; however, it is the quieter babies that tend to serve as a reminder that something sinister could be taking place. When a doctor attempted to take blood from Tay, he did not flinch or make a sound. My heart sank; instinctively, I feared that something was seriously wrong. I expressed concern about his brain, as he didn't seem able to register the pain, yet it was clear from his face that he was in discomfort. My concerns were dismissed and we were sent home.

Over the next 24 hours, Tay became increasingly non-responsive and his breathing became more erratic. When a midwife attended to do a heel-prick test, he barely opened his eyes. I returned to A&E insisting that he be admitted. We were sent to the birthing centre and he was placed on broad-spectrum antibiotics. There was no real sense of urgency or concern about his condition and I questioned if I was just being an overbearing new mum. Later that night, Tay's body became floppy and he stopped feeding. Finally, we saw a doctor who ordered a lumbar puncture for suspected meningitis.

Finally, I felt I was being listened to and my anxieties acknowledged, which was both a blessing and a curse. Tay underwent brain scans, blood tests and viral culture testing. The doctors could come to no clear agreement about what was causing him to deteriorate and they classed him as a bit of a mystery. I was frustrated that I couldn't understand why he was worsening by the hour, when he was on morphine and receiving respiratory support.

I was told that Tay's condition wasn't a ‘life-or-death situation’. Later that evening, Tay began having convulsions. This was the confirmation I needed that the illness was related to his brain. I felt that his treatment up until this point was not sufficient and asked for him to be transferred to another hospital. As they were preparing for the transfer, Tay's heart stopped beating; they fought to bring him back to life while I watched, helplessly, behind a screen. I could hear loud beeps and saw worried faces all around. Hours earlier, I had been assured this wasn't a life or death situation, yet now here I was, facing just that. They stabilised his condition and I was told that he was unlikely to make the short journey to the next hospital. The journey was awful. When we arrived, I was not allowed to see Tay for 5 agonising hours. When I did see him, he was lost in a mass of clinical tubes, monitors, machines and on dialysis. He was unrecognisable and his body was swollen three times its normal size.

When a doctor came to confirm my son's condition, after a week of tests and misdiagnoses, I was stunned. ‘Your son has neonatal herpes,’ he told me. I remember letting out a bemused laugh and saying, ‘Herpes? How can he have herpes? I don't even have herpes! He's a baby—how can he have a sexually transmitted disease?’ I had never heard of neonatal herpes; never had genital lesions or even a cold sore. I simply could not comprehend how he had contracted it and feared that others would assume that I had somehow passed on the disease to my baby.

In a strange way though, I felt a little reassured. I comforted myself with thoughts of ‘at least it's not cancer’ and ‘I've never heard of anyone dying of a cold sore before’. I dismissed the medical team's concerned tones and warnings that the condition was serious, preferring to believe that they were saying that as a precaution. I never once believed the virus would actually claim my son's life and looking back, perhaps it was just as well, because the hope kept me focused and strong.

It transpired that Tay had contracted the virus through a graze he had on his face when he was delivered by forceps. As I had no history of the virus, Tay was (ironically) more at risk because he did not have any maternal antibodies. Someone who had close contact with him while they had an active bout of the virus had kissed this area of his face where the skin was broken. I was shocked to learn this, as I had never known that risk existed. My mind raced as I tried to think of every single person who had ever visited, held him, kissed him or been in close contact with him. It seems silly now I know more about the virus, but at the time I felt embarrassed to tell my relatives that he had neonatal herpes because I was scared they would react as I did—after all, it is not an illness normally associated with a baby, and herpes still carries a negative stigma.

Tay then had to be transferred to another hospital due to liver failure, where the medical team affectionately referred to him as ‘their little hero’. Despite some small signs of improvement, Tay suffered a cranial bleed in his brain and I was told his life support would need to be removed.

I was heartbroken as I watched his heart rate plummet. The happiness he imparted, and the hope and joy he had brought into my life, was over as quickly as it started—now he was just a simple flat line on a monitor. The weeks before I had been excitedly choosing cots; now I would have to choose a coffin. He fought hard, but the infection won the battle. There is no pain comparable to that of losing a child. If just one person had considered neonatal herpes earlier in his journey, I could be sharing a very different story.

Understanding the virus

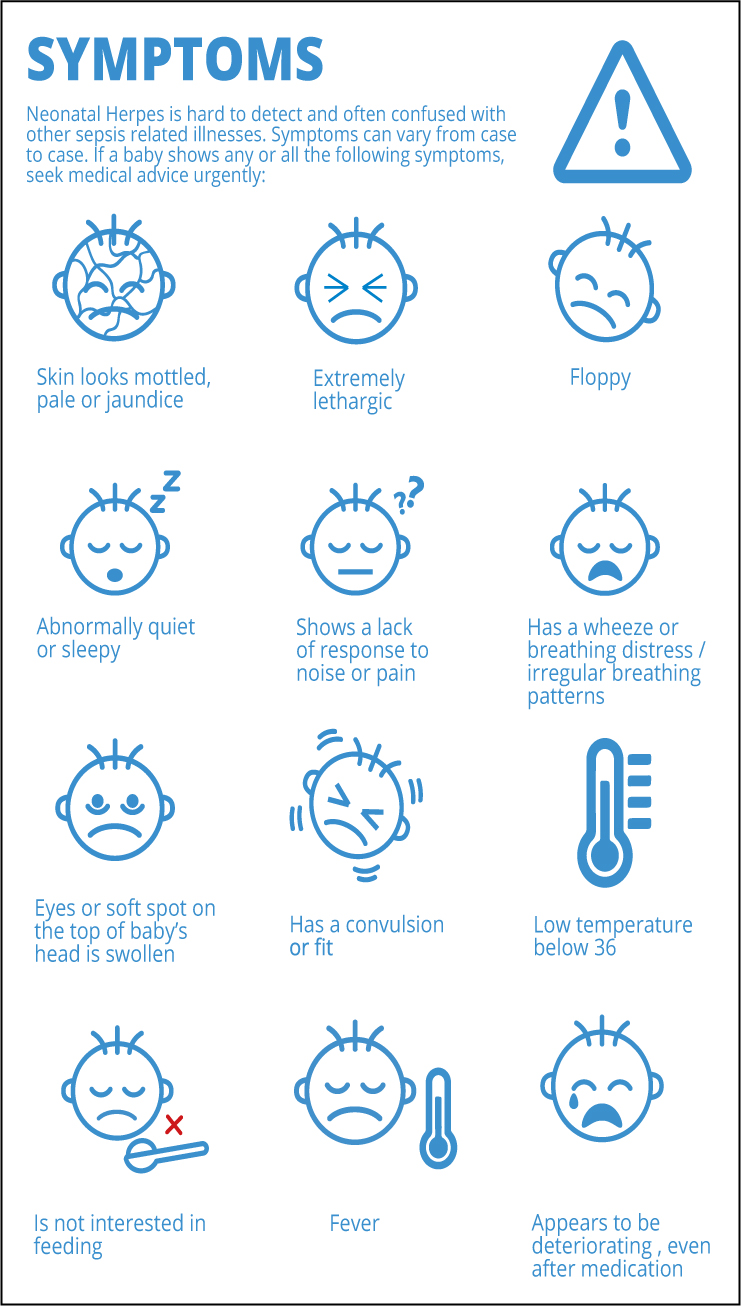

After Tay's death, I asked myself relentless questions about why I hadn't known about neonatal herpes, why no one had mentioned it, why it took so long to diagnose, and who Tay had contracted it from. I spent weeks trying to find doctors or medical professionals who could help me make sense of what had happened, but they were few and far between. Nobody could give me the answers I needed, so I researched medical journals, watched medical seminars on YouTube and read clinical trials to learn and understand more. I discovered that the symptoms of neonatal herpes are often mistaken for more common baby illnesses such as sepsis, strep B and meningitis. Because of this, medical professionals often consider neonatal herpes later in their investigations, by which time the damage is done and it is too late. There also is no one-size-fits-all set of symptoms, which makes neonatal herpes notoriously hard to detect. In Tay's case, more attention should have been paid to his extreme lethargy, raised ALT levels and his lack of response to pain and external stimuli. The viral cultures taken from him did not show that the infection had reached his brain and no one had highlighted or followed up his raised ALT levels, which would have been a key indicator that he had organ failure in the first few days of his admission to hospital.

I was shocked that key signs and indicators were missed or not followed-up. It was apparent that there needed to be more resources and education available for parents and neonatal staff. My research had identified a real lack of credible information and so I saw an opportunity for better awareness, education and training for medical professionals to address the misinformation. I pledged to myself that no other parent would have to find out about neonatal herpes like I did and that I would try to create resources that people could access if they found themselves in the same unfortunate predicament.

Losing my son to an illness that could have been preventable and treatable (if identified at an earlier stage), propelled me into action and in that moment, feeling lost, confused, frustrated and heartbroken, ‘What's In A Kiss?’ was born.

Raising awareness

At the time, I was informed that not much is written about neonatal herpes because of the fear of scaring the public. I decided that a poster to raise awareness would be a good starting point, to prompt people to think, ‘I didn't know babies could get that’. It would start a much-needed conversation. Initially when I launched my poster, many people were worried it would send the wrong message, but I felt that most people would prefer to know and be scared, rather than oblivious and bereaved.

As I have a full-time job, I used my days off and personal finances to fund the posters and eventually managed to persuade local hospitals and the NHS to support it. After that, several health professionals contacted me and over the years we have continually created, provided and financed resources that people can obtain from their GPs, hospitals or baby apps.

Conclusion

Neonatal herpes affects one or two babies in every 100 000 live births; however, I would suggest that the prevalence is certainly increasing: I have heard of at least six cases in the UK in 2019 so far. It is well documented that babies who contract this condition in the first 4-6 weeks of life are likely to die or suffer irreversible brain injury and multiple organ failure. Babies are at the highest risk within their first 28 days of life. If undetected, the infection spreads alarmingly quickly and is incredibly destructive. A baby's survival is largely down to health professionals' proactivity in identifying the illness and administering acyclovir as a precautionary measure if a baby continues to deteriorate following broad-spectrum antibiotics.

I am proud that my resources and campaign have been well received, and I am always grateful to receive calls or messages from the countless parents who contact me, searching for information or answers. I have also helped many mothers whose babies are in hospital or who have sadly died from neonatal herpes. I would be lying if I said that I didn't take it personally when I learn that the awareness didn't reach them. This is why I know that I have much more work to do so that all parents are informed of this illness during their pregnancies and after the birth.

Prevention and awareness are the only weapons we have to fight this deadly virus while we wait for more research. In 2019, three babies have already been saved because of the increased awareness and early medical intervention, which assures me that a change is slowly but surely coming. This year, my campaign will launch its official webpage. We have e-module training for health professionals under construction and we are running midwifery workshops in hospitals and universities throughout the year. In addition, I will continue offering bereavement support to parents who find themselves in this tragic situation, as it helps me to heal, knowing that I can be of service to others. I would encourage all health professionals to refresh their knowledge of neonatal herpes and the symptoms to look out for. If presented with a mystery baby like Tay, your quick thinking could be the difference between a baby's life or death.

Knowing that Tay's story has saved lives has been an overwhelming experience. His legacy is the only imprint that is left to show that he ever existed in the world. As long as I am alive I will continue to ensure that his legacy lasts forever and that his fight was not in vain.