Recent years have seen growing consensus that global health dynamics still need ‘decolonisation’ (Kim et al, 2019; Hindmarch and Hillier, 2023). Momentum has been building in humanitarian circles for decades, but wider social movements like Black Lives Matter have given way to a distinct ‘moment of reckoning’ (Krugman, 2023). In maternity care, the main imperative comes from a glaring inequity: people living in, or descended from, countries previously oppressed by Western powers are still far more likely to lose their life during pregnancy, childbirth, the postnatal period or as a newborn (Knight et al, 2023; Unicef, 2024; World Health Organization (WHO), 2024).

This article assesses global health conference culture through the lens of decolonisation theory (O'Dowd and Heckenburg, 2020; Krugman, 2023), and considers potential implications for maternal and newborn outcomes. It then takes WomenLift Health as a case study to explain the practicalities and benefits of holding an international summit in a country facing disproportionate challenges with midwifery-related sustainable development goals (United Nations (UN), 2023). Jacqueline Dunkley-Bent, global chief midwife, highlighted why the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM, 2023a) prioritises meeting in regions with the greatest need for accelerating universal, high-quality midwifery.

The problem: where is health policy made?

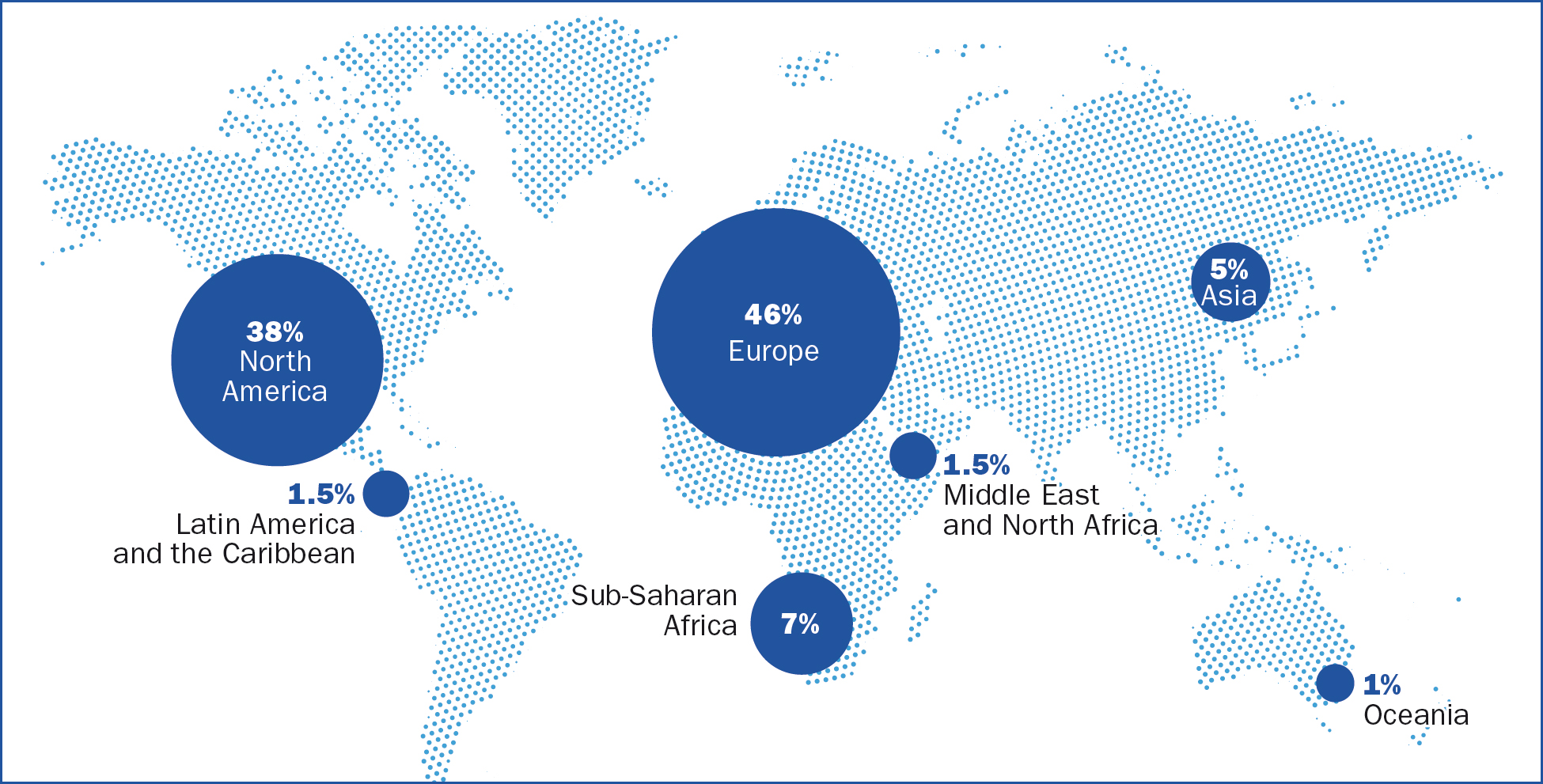

Despite talk of ‘bottom up’ strategy, global health conferences often still perpetuate a mechanism of ‘top down’ agenda-setting by wealthy nations (Smith, 2006; Horton, 2019; Khorsand et al, 2022). One analysis of 112 summits found that 96% were held in high-income countries, with only a third of delegates coming from the resource-poor contexts that were the primary focus of discussion (Velin et al, 2021). The researchers identified five barriers to attendance: financial challenges, visa restrictions, political issues, racism and limited speaking opportunities (Velin et al, 2021). One global health academic has encapsulated this dynamic as ‘Davos syndrome’, referring to the Swiss ski resort where the world's richest people gather annually to talk about poverty (Pai, 2018). It all points to a tendency for the ‘minority world’ (influential nations, predominantly north of the equator) to talk about, rather than with, the ‘majority world’ (low- and middle-income countries, usually in the south). The map in Figure 1 illustrates one factor in the geopolitics: 85% of global health bodies have headquarters in Europe and North America (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

The impact: how does this compromise maternity outcomes?

It follows that those working in contexts with the highest maternal and neonatal mortality rates are less likely to be part of identifying solutions (Velin et al, 2021). Concerns have already been raised by reports including the state of the world's midwifery (United Nations Population Fund, 2021), which showed that midwives do not always have a say in how to build capacity in maternity services and meet women's needs.

One metric for whether programmes are working can be found in countries’ track record with the UN's (2023) sustainable development goals. Those most pertinent to maternal, neonatal, sexual and reproductive health are goals 3 and 5. Goal 3 is good health and wellbeing, which includes universal family planning and sexual healthcare, as well as targets to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths. Goal 5 is gender equality, which includes the end of forced marriage and female genital mutilation, support for those doing unpaid domestic chores and equal access to leadership jobs regardless of sex (UN, 2023).

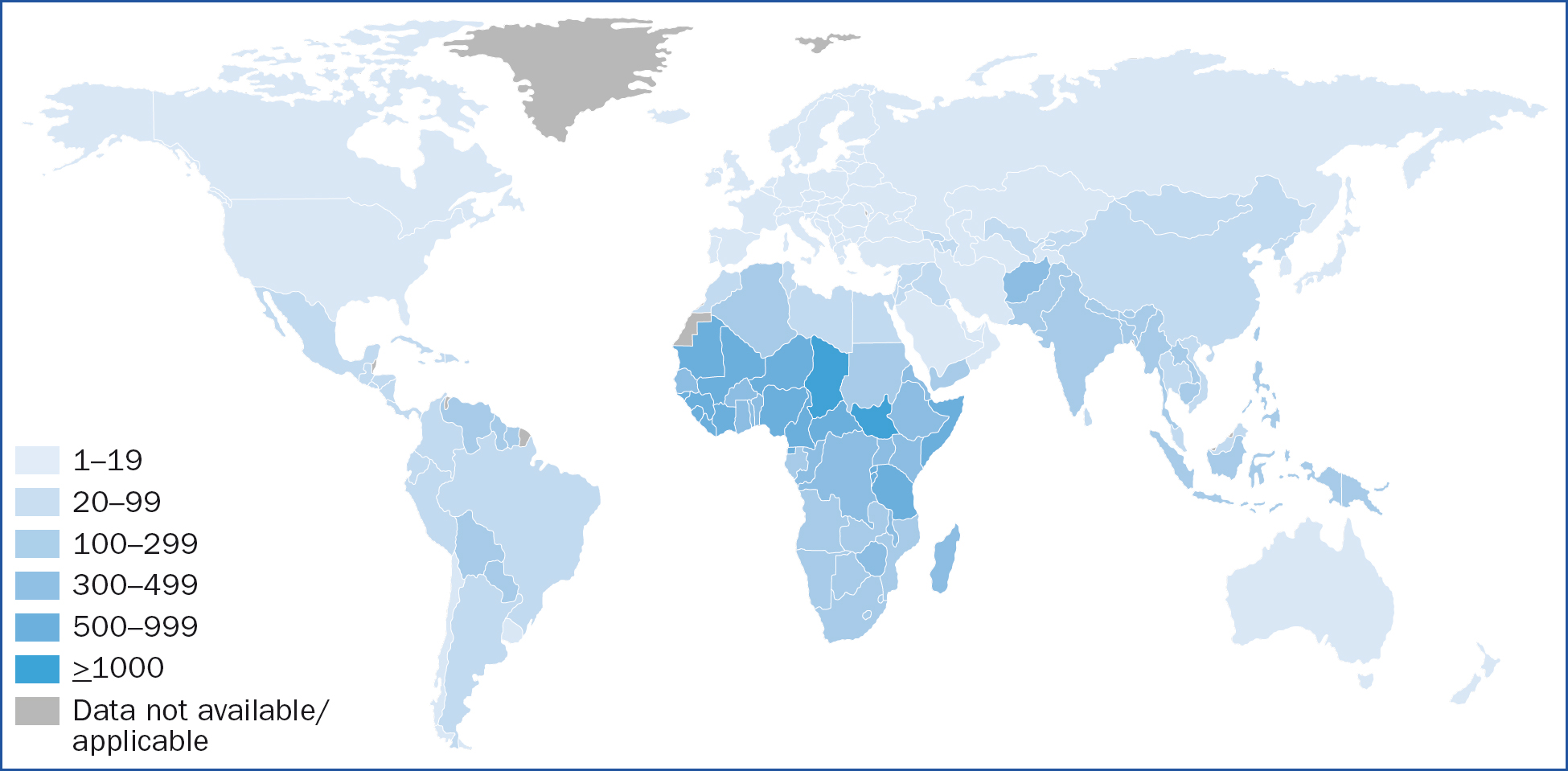

The world is not on track with these targets, and inequity pervades the picture. The latest available global maternal mortality ratio stands at 223 per 100000, over three times the goal of 70. Every 2 minutes, a mother dies and 70% of these deaths are in sub-Saharan Africa, as shown by the map in Figure 2 (WHO, 2024). The neonatal mortality target is 12 per 1000 live births, but 18 in every 1000 newborns still die within the first 28 days. Again, a disproportionate number of these deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa, contributing to a regional rate of under-5 mortality that has only just reached the global average achieved 20 years ago (UN, 2023).

The metrics: slow progress on sustainable development goals

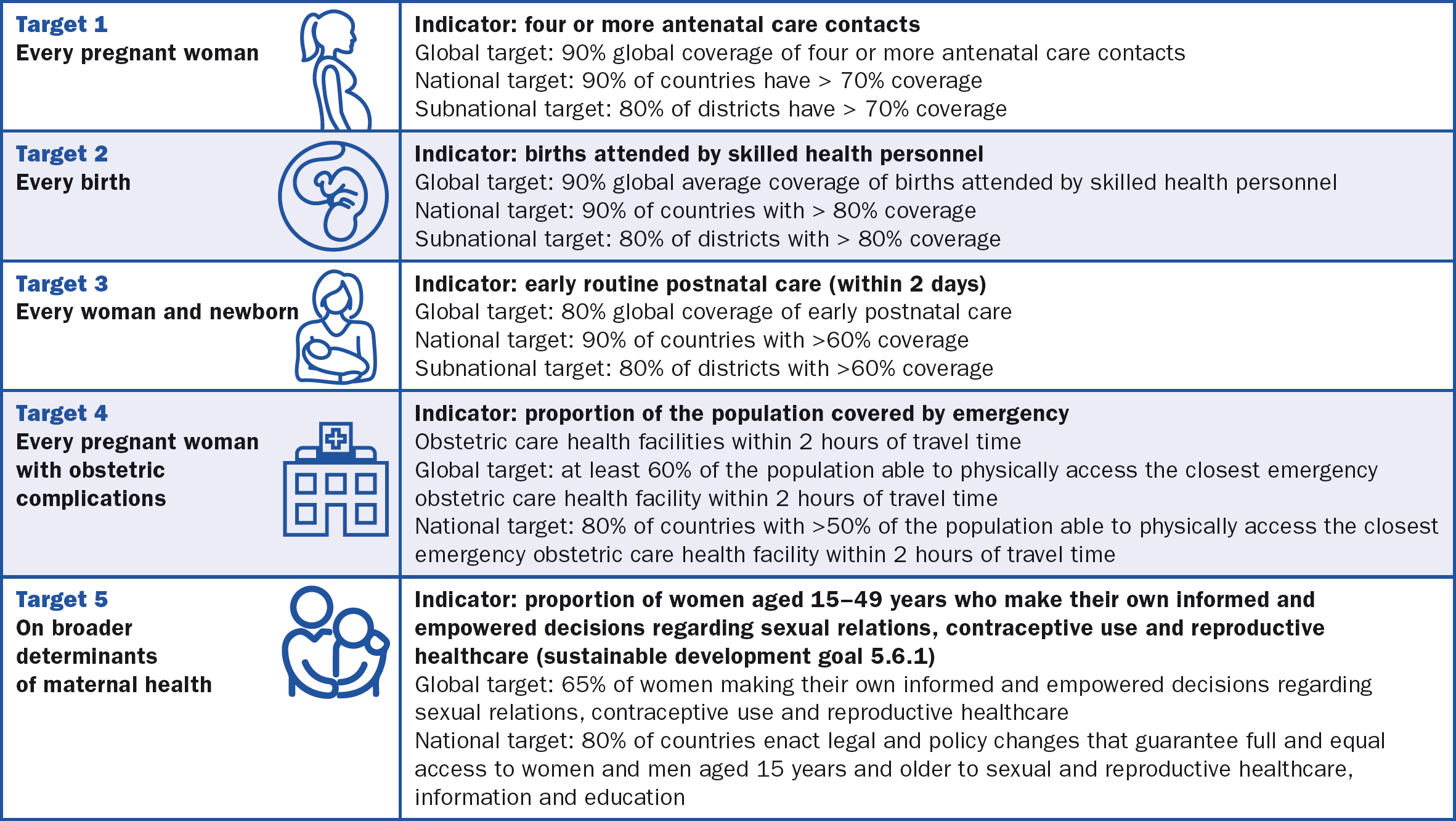

The reasons for slow progress with the goals are beyond the scope of this article; they include broader geopolitics and economics, fundamental challenges in low- and middle-income countries with infrastructure, procurement and financing and issues of politics and culture (Grown et al, 2014). However, the under-representation of experts from the majority world at global conferences is arguably a factor hampering a bottom-up approach. ‘Localisation’ has been a buzzword in policies to tackle the sustainable development goals since their launch in 2012, but the world is dealing with legacies of colonialism that hamper progress (Smith, 2006; de Campos et al, 2024). For instance, the WHO's (2021a) ending preventable maternal mortality campaign emphasises the importance of ‘tailoring responses to the countries where women face the greatest risks’ and urges under-performing governments to have national maternity policies with steps to actively address each sustainable development goal component, as laid out in Figure 3. But building capacity costs money, and just 2.1% of global humanitarian assistance is given at a local or national level (Development Initiatives, 2023). While low- and middle-income country dependency on high-income country donors is acknowledged to be a problematic dynamic in itself, there remains widespread agreement that the most reasonable course in an imperfect world is one of ‘non-abandonment’. This is the idea that a former power, having disrupted a country, has a duty to continue supporting where it can (de Campos et al, 2024).

A solution? Moving south

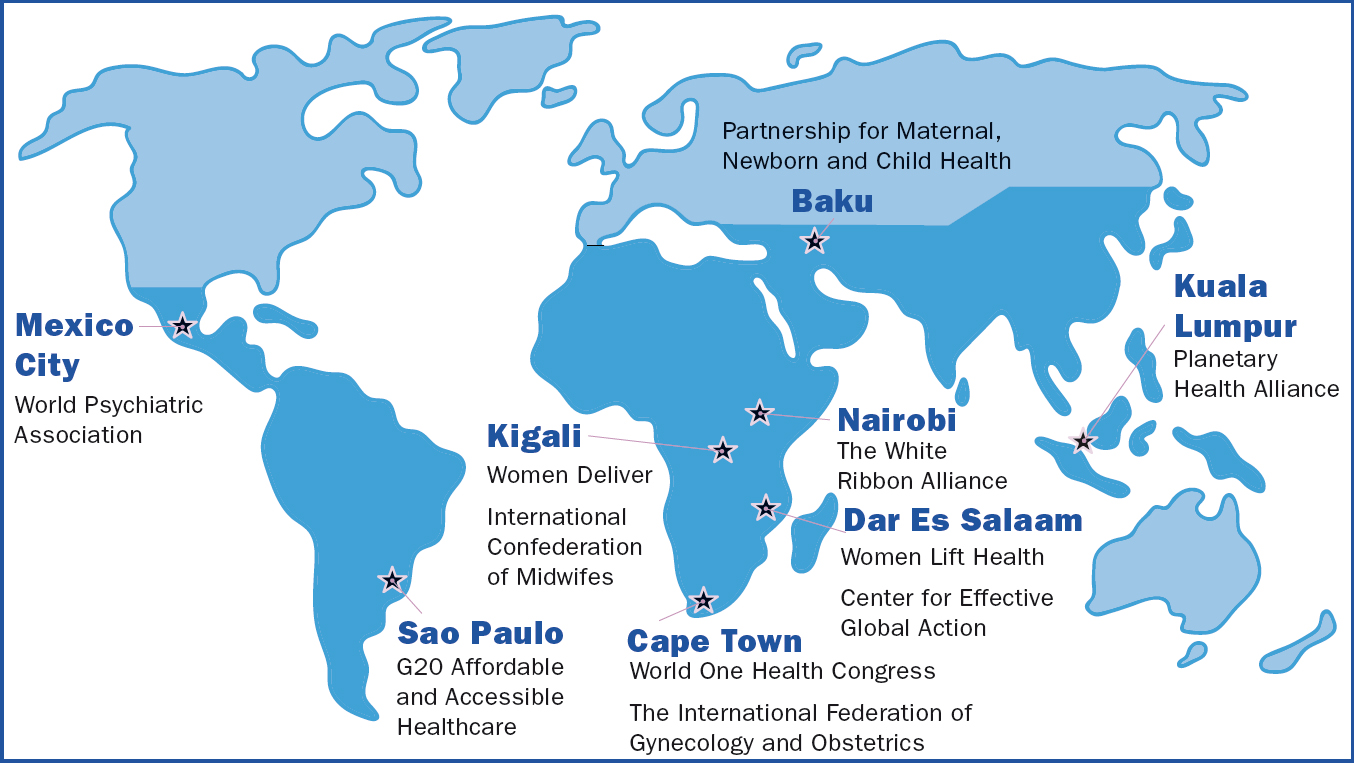

Increased awareness about post-colonial dynamics, along with the ‘moment of reckoning’ in global health circles, has prompted greater efforts to reform how and where policy is made (Krugman, 2023). The following case study reflects a wider trend of non-governmental organisations making an intentional shift to convene in regions of focus, as illustrated in Figure 4.

WomenLift Health global conference

A conference convened by WomenLift Health in 2024 sought to address barriers to equitable representation of experts from low- and middle-income countries. It also reported insights from clinicians from the region, who had a platform because of the deliberate action of WomenLift organisers to amplify majority world viewpoints on how to tackle context-specific issues in maternal, neonatal, sexual and reproductive health.

Background: tackling the gender gap in health leadership

WomenLift works to improve health outcomes and gender equality by investing at an individual, institutional and societal level to close the gender gap in health leadership worldwide. The fast-growing non-governmental organisation gathered steam after the WHO (2021b) revealed an underused talent pool: while 70% of the world's healthcare is provided by women, females get just 25% of top jobs. In the poorest countries, that number falls to 5% (WHO, 2021b). With funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, WomenLift now has hubs in East Africa, the US and Canada, India and southern Africa. Their focus is on developing mid-career women and influencing the environments where they live and work (WomenLift Health, 2023). Actions include mentoring to help people get past personal obstacles to career progress, the creation of networks who boost health outcomes (and each other's job prospects) and thought leadership to tackle gender bias that otherwise stalls women at the peak of their potential. Given that WomenLift's core work involves tackling conventional power structures, the programme naturally extends to addressing broader intersectional barriers, including global conference inequity.

The location: Tanzania

In April 2024, WomenLift convened more than 1000 stakeholders from 41 countries in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Delegates travelled far from UN headquarters, global campaigns, Western corporation donors and private foundations. The summit also heard directly about the nuts and bolts of working in the world's most under-resourced communities, listening to clinicians, finance officers, technical managers, hospital administrators, local health authorities, community advocates, local academics, health advocacy practitioners and social enterprise projects.

WomenLift's communications and engagement director Lizz Ntonjira encapsulated a primary reason why East Africa was their chosen location: ‘global health conferences are mostly held in the global north, ironically with the goal of addressing critical health gaps that are eminent in the global south … conference inequity is a pervasive issue marked by limited attendance from [low- and middle-income countries], often due to systemic barriers' (Velin et al, 2021). WomenLift were also responding to calls for greater representation of global south participants, collaboration between global and local health actors and opportunities to speak, present, and network (Development Initiatives, 2023). Ntonjira added that ‘this in turn helps shape agendas informed by and aligned with local needs' (Development Initiatives, 2023).

The evidence: visa discrimination

Visa discrimination is an existing issue (Hawkes, 2018). Defensive immigration policies can make it harder to travel from poor countries to rich ones, with visa fees that can harm low-income groups the most (Wairu, 2018; Weaver, 2018; Velin et al, 2021; Tsanni, 2023). When WomenLift was starting out, 17 delegates were refused entry to attend a UK meeting, prompting the director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to write to the UK Home Secretary. He said ‘our school is already considering moving the locations of many of our large international meetings to outside of the UK so that valued global experts can participate more easily’ (Piot, 2018).

The action: minimising visa restrictions

WomenLift chose Tanzania, a relatively ‘visa-friendly’ country compared to many in the global south as it requires no visa at all from citizens of 70 countries, many in east and southern Africa. This saved visa fees and allowed those on tighter budgets to book flights early, further cutting costs.

The impact: giving voice to local midwives

Midwives from Cameroon, Uganda and Kenya needed no visa to join the official ICM delegation. Harriet Nyega, leader of Midwife-Led Community Transformation, a coalition in Uganda, spoke about the practicalities of reaching marginalised women, including adolescents. This informed high-level stakeholders who are able to influence global maternity policy, including Anne Kihara, president of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics.

The evidence: low- and middle-income country participants may be seen but not heard

Analysis has shown that acceptance rates for conference presentations by researchers from low- and middle-income countries remain lower than acceptance rates from high-income countries, meaning that even if delegates are able to attend, the opportunities to influence discussions are proportionately few (Kpokiri et al, 2024). Factors for this include language barriers, less developed academic infrastructure and limited access to networks. This has prompted calls for culturally appropriate mentoring. ‘Epistemic injustice’, where knowledge is taken either more or less seriously based on the person who knows it, is a persistent post-colonial bias that affects how research is funded, authored, published and presented (Horton, 2019; Bhakuni and Abimbola, 2021).

The action: building confidence for public speaking

WomenLift has leadership journeys that integrate mentorship programs in the respective hubs in India, east Africa and southern Africa, where senior health academics offer mid-career researchers tools for pitching convincing proposals to world-class conferences (WomenLift Health, 2024). By building infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries, WomenLift is promoting a research and policymaking environment more ready for authentic partnerships with institutions in the global north. This nurtures ‘agency within the context of tailored assistance driven by community needs’ (in other words, responsive support), which experts have pinpointed for the pursuit of ‘global health justice’ in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (de Campos et al, 2024).

The impact: platforming an advocate for reproductive rights in South Sudan

A plenary ‘spotlight talk’ was given by WomenLift's alumnus Idyoro Ojukwu, the first female obstetrician in South Sudan, which has the highest maternal mortality rate in the world: 1223 per 100000 (Unicef, 2023a).

‘There are teenage pregnancies, child marriages – [and for those people] there is no contraception. Once married, women are meant to give birth until the menopause’. Dr Idyoro Ojukwu

She shared firsthand experiences to explain factors leading a country like hers to lag in the sustainable development goals. Describing caesarean sections she had performed in the rural health centre near her family home, she said the only available pain relief was ‘diazepam and local anaesthesia – to save a life’.

‘Women die in labour, some on their way to the health facility, some there [at the health centre, where they are] unattended too. Some develop fistulas, if they survive the labour’. Dr Idyoro Ojukwu

Highlighting the gap between policy and practice, she discussed how cervical cancer is detected too late for women to be treated, adding that ‘the WHO set goals in 2018 – but my country still doesn't have a cervical screening programme. Women die on the wards, due to lack of facilities. There is lack of skill and personnel’. Dr Idyoro also explained complex challenges in sexual and reproductive health, telling the story of a girl orphaned at 9 years old.

‘At the age of 10, she was raped. By 15 years, she was HIV infected. She presented at the hospital aged 19, with end-stage cervical cancer, and she died aged 20. This is a story heard around many countries in Africa’. Dr Idyoro Ojukwu

The evidence: prohibitive costs

Data show the disproportionate cost faced by someone travelling from a low- or middle-income country to a high-income country, compared to their equivalent going in the opposite direction (Khorsand et al, 2022). For those living and working in weak or emerging economies, exchange rates can be prohibitive (Velin et al, 2021). For instance, the World Health Assembly, which takes place every year in Switzerland, requires attendees from around 150 countries to face visa fees and requirements, and to pay to stay in Geneva, the seventh most expensive city in the world (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2023).

The action: adjusting fees and economising

Anyone attending the Dar es Salaam conference from a low- or middle-income country paid half price to register. This equitable approach has been adopted by many global health organisations, but charging according to means is not universal (Arend and Bruijns, 2019). For WomenLift's delegates, the money came from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and corporate firms, along with support from Co-Impact and End Malaria. By gathering people in Tanzania, WomenLift demonstrated alignment with its main sponsor, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (2024), which states ‘solutions to Africa's greatest challenges can come from within Africa’. A cost-saving mindset pervaded other areas of WomenLift's logistics: the meeting was held in low season and over a weekend when corporate hotel and conference venue rates are lower. It hardly needs stating that average services cost less in Tanzania than in any high-income country.

‘Side benefits of the summit came from delegates supporting local businesses, building rapport with the host government and fostering trust in neighbouring communities. Working side by side on a big project, and then making it happen, really shows you can walk the talk’. Lizz Ntonjira

The evidence: prejudice and indignity

Racism is also an evidenced barrier to full participation at global conferences (Velin et al, 2021). Attendees from low- and middle-income countries reported facing prejudice from people in high-income countries. For instance, ‘fears they would apply for refugee status on arrival’. One Rwandan researcher described a 14-hour wait for a visa to attend the World Health Assembly and the ‘cognitive load’ of not knowing whether he would make it, having missed two other presenting opportunities within a year (Alayande, 2023). He said the conferences themselves could be alienating and called for a more welcoming climate, adding ‘just arriving at a meeting is not enough’.

The action: opening channels

WomenLift put stepping stones in place to help delegates enter Tanzania.

‘We worked with the immigration department to expedite visa processing, and with the airports authority to set up a booth at arrivals to ensure seamless logistics for all delegates’. Lizz Ntonjira

The conference organisers were also deliberate in opening social channels, both in-room and virtual, to open networking opportunities for delegates who might feel excluded (Alayande, 2023).

‘We wanted to confront a range of barriers that can stop people connecting, to help those who might not otherwise have had the means or the nerve to make contact’. Lizz Ntonjira

Opening remarks by WomenLift's president Amie Batson urged every participant to ‘say hello to someone you don't know’. She then waited 5 minutes for people to mix.

‘To tackle our biggest challenges, we need both women and men at decision-making tables, bringing a diversity of perspectives, experiences and of course expertise. Understanding the challenges, designing the solutions, determining the policies, implementing the action – it all needs to be done with equal participation of women – fully half the population’. Amie Batson

Another ready way of making contacts was a dynamic conference app for direct messaging between any delegate on the list, regardless of rank. Further, a ‘mentorship breakfast’ brought health workers, including many midwives, to sit at tables of 10 with a senior leader. Q&A sessions, all consciously informal, during plenary and break-out panels also helped bring newcomers in.

‘It costs nothing to be friendly, but the dividends of expanding the conversation can be great. Global health is an ecosystem; all parts need each other. So we created “soft spaces”, with informal seated areas and an overall tone of relaxed openness’. Norah Obudho, WomenLift's East Africa director

Benefits of being ‘on the ground’

Being located in a country still grappling with the sustainable development goals allowed delegates to witness first-hand challenges faced by maternity clinicians in a resource-poor context. WomenLift held a field trip to a treatment centre for women recovering from obstetric fistula, which can cause permanent urinary and fecal incontinence if untreated. A complication of obstructed labour, the injury disproportionately affects women in low- and middle-income countries, with an estimated 500000 facing aftereffects that are physically, mentally and socially debilitating (Ruder et al, 2022). The sustainable development goals aim to eliminate it by 2030, but that is looking unlikely (Maternal Health Thematic Fund, 2024).

WomenLift's delegates visited the Mabinti Centre, in the capital city Dar es Salaam, to hear about issues including social stigma that compromises women at home and work; delayed diagnoses for lack of bright lights; life-threatening haemorrhage; and sepsis (Ruder et al, 2022). Being on the ground overcame what one academic called ‘sitting in fancy hotels and resorts … disconnected from the reality’ (Pai, 2018).

A field trip: cashflow for survivors of childbirth injury

WomenLift invested in a social enterprise based at the Mabinti Centre, buying beadcraft conference lanyards from survivors who had been equipped with skills and machines to make accessories and toys. WomenLift also hosted a pop-up Mabinti shop. One seller said WomenLift was helping challenge stigma, adding ‘we have suffered. But this is a chance to take money home and be proud’.

International Confederation of Midwives

The ICM Global Chief Midwife Jacqueline Dunkley-Bent travelled to Tanzania from the Netherlands to collaborate with partners in the interest of optimising maternal and newborn outcomes across the world. The ICM (2023a) ‘push for midwives’ campaign continues to call for 900000 more midwives who are well trained, regulated and supported, many of whom are needed in sub-Saharan Africa. As the global champion of quality midwifery care, the ICM convened members in Kigali, Rwanda in September 2024.

‘Holding regional conferences is an important way to ensure that midwives can more easily access our events and the professional growth they offer. It also helps lower the carbon footprint and costs of travel’. Prof Dunkley-Bent (ICM, 2023b)

Counter arguments

Changing the location of global conferences will not single-handedly improve outcomes linked to the midwifery-related sustainable development goals. Global health bodies face challenges when gathering people in low- and middle-income countries. Issues include south-south visa restrictions, delegate security and brand damage by association with governments whose human rights record may be questionable (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2024).

Conclusions

Meaningful ‘decolonisation’ of maternal, neonatal, sexual and reproductive health policy needs to listen and respond to clinicians working with the world's most vulnerable women and babies. WomenLift Health has demonstrated how and why organisations are hosting summits in regions most lagging with the UN sustainable development goals. Their 2024 conference in Tanzania empowered midwives from a range of low- and middle-income countries to bring localised insights on optimising maternity outcomes. By sharing opinions with policy influencers including UN agencies and major donors, these midwives promoted the ICM campaign for universal, high-quality midwifery.

Key points

- Most global health conferences happen in high-income countries – which restricts attendance from nations lagging on the midwifery-related sustainable development goals.

- Under-representation of the ‘global south’ hampers the locally-driven approach necessary for maternal, neonatal, sexual and reproductive health policy to tackle context-specific challenges.

- Bodies like WomenLift Health and the International Confederation of Midwives are turning the tide by holding conferences in low-and-middleincome countries.

- WomenLift Health's summit in Tanzania gained insights from midwives, obstetricians and sexual and reproductive health experts to inform policy for the most vulnerable.

- The International Confederation of Midwives, which held a regional conference in Rwanda in September 2024, says further benefits include cutting the carbon footprint and costs of travel.

CPD reflective questions

- How does the evidence on conference inequity relate to your own professional life?

- How can maternity workers and academics best support colleagues facing structural disadvantages?

- How might the legacy of colonialism affect the experience and outcomes of maternity service users in the context where you work?

- Consider the issue of ‘epistemic injustice’. How might this affect you and your colleagues?