The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) holds the overall responsibility for regulation of midwives. Following the removal of statutory supervision in 2017, a new model of employer-led supervision, A-EQUIP (Advocating for Education and Quality Improvement) was introduced in England (NHS England, 2017). NHS Trusts should now follow the same investigation and supervision of practice process for all staff (NHS England, 2017). The other three countries in the UK have also adopted employer-led models of supervision, but have chosen to continue to use the term ‘supervisor’ rather than professional midwifery advocate (PMA). A-EQUIP was introduced in seven pilot sites throughout England in 2017 and implemented locally at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust in 2018.

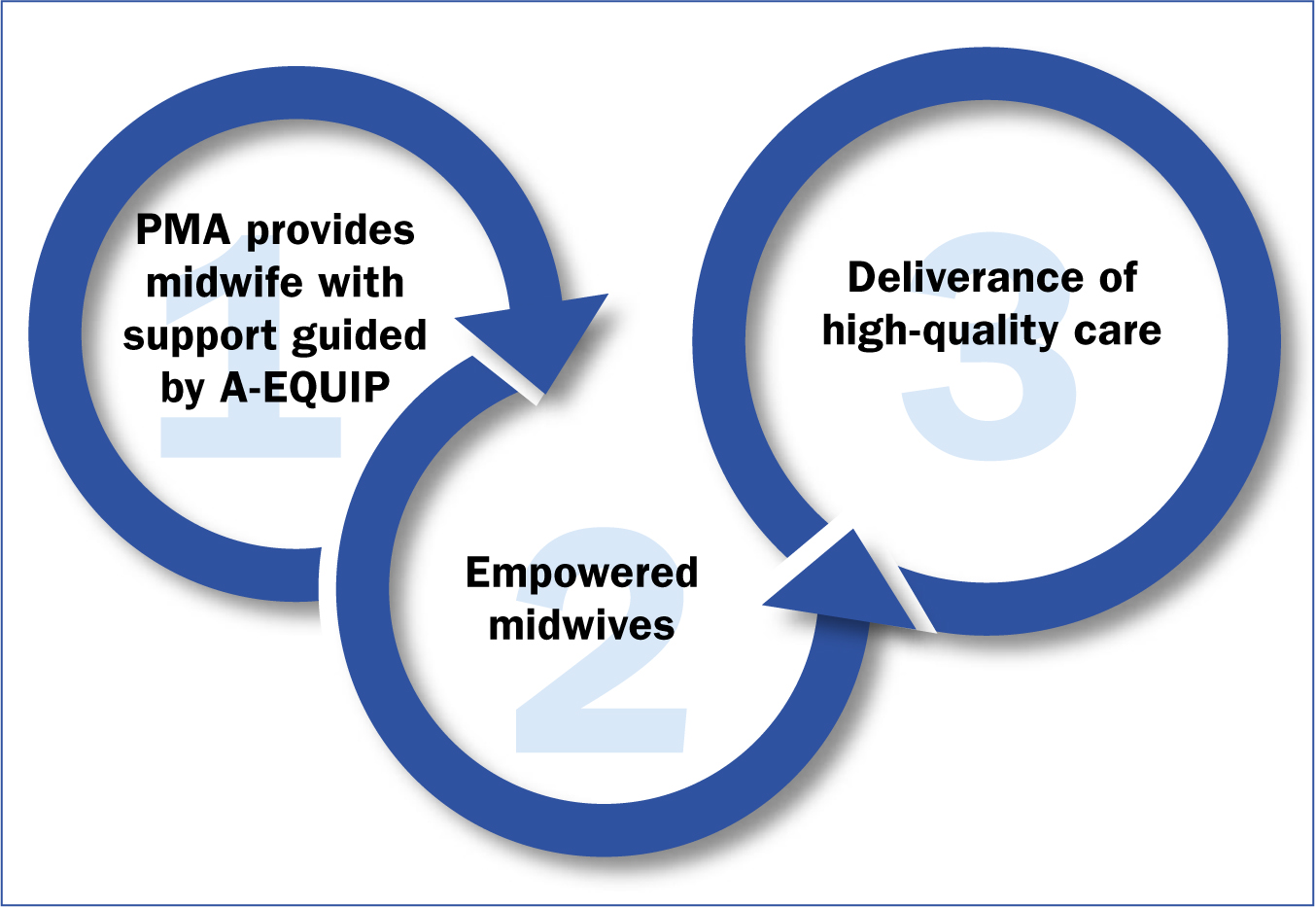

NHS England (2017) studied the needs and requirements for midwives, present and future, during the development of A-EQUIP. Some of the stresses and pressures emphasised in today's workplace are not necessarily new; Kirkham (1999) also highlighted inadequate skill mixes, low staffing numbers and long working hours. More recently, the Mind the Gap report (Jones et al, 2015) discussed ‘Generation Y’ becoming an increasing part of the workforce and highlighted the requirement for employers and educators to consider models of supervision as a strategy to support staff according to the likely needs of each generation. Similar pressures have been recognised by the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) in Why Midwives Leave—Revisited (RCM, 2016). This evidence reinforced the continued strain that midwives face in the workplace and the requirement for support to enable them to manage pressures and carry out their role to the best of their ability. Supervision, in its supportive function, is still considered a principle part of midwifery practice and in light of this, the supervisor of midwives role has been replaced by the PMA (Figure 1).

Restorative clinical supervision

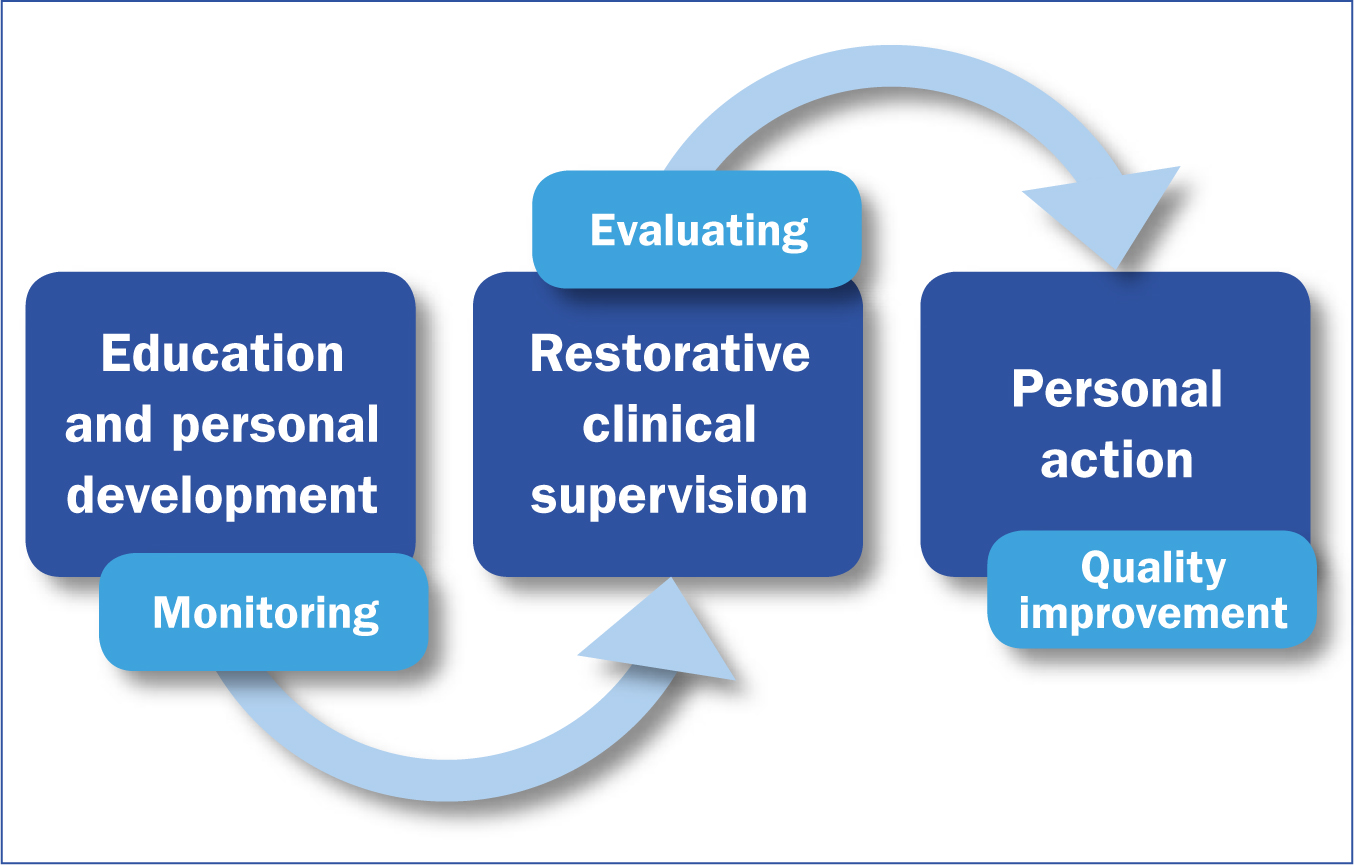

The PMA role encompasses a wide range of supportive measures for midwives and is underpinned by A-EQUIP (NHS England, 2017). The model has four distinct functions: normative, restorative, personal action for quality improvement and education and development (Figure 2). This reflection focuses principally on the restorative function.

Restorative clinical supervision is led by PMAs. It offers midwives the space and time to process experiences, supporting them to increase their levels of resilience and outlining coping strategies for the future. The ultimate goal of restorative clinical supervision is to offer midwives a safe environment to consider options, reflect constructively and challenge negativity; this in turn could empower the individual to realise what they can do themselves to improve their working life and reduce stress and burnout (de Haan, 2012).

Restorative clinical supervision and its benefits are explained in great detail by Wallbank (2014), and are a key aspect of the PMA role. The PMA must be able to instil positivity, raise self-awareness and increase understanding in staff, so that individuals who are motivated through restorative means, are generally encouraged to continue progressing towards positive goals, both personally and professionally (Wallbank, 2014; NHS England, 2017). A positive relationship between the PMA and the midwife provides the building blocks for successful restorative clinical supervision, with a focus on creative and collaborative learning, which leads to personal and professional growth. This in turn allows the support and monitoring of midwives and overall, contributes to the welfare and safety of women (Pettit and Stephen, 2015). PMAs must be aware that restorative clinical supervision is influenced by personal values, life experience and knowledge of the different components in which supervision can be provided. Wonnacott and Wallbank (2016) acknowledge the apparent confusion between different types of supervision in healthcare and explain how restorative clinical supervision can be effective for practitioners. Inskipp and Proctor (2001) refer to different tasks of supervision and Proctor's original model of clinical supervision (Proctor, 1986) (Figure 3), which was used in the development of A-EQUIP, provides further insight into understanding this method.

Supervisory relationships formed and developed on the idea of person-centeredness offer greater depth of learning, personal self-awareness, professional growth and feelings of respect and trust (The Person Centered Association, 2018). Proctor (2004) agrees that by feeling received, the ‘supervisee’ feels safe, understood and valued, making them more open to supervision. In addition, the psychological needs of learners should be addressed to enable their motivation to learn. Maslow (1987) provides a useful tool for highlighting the importance of meeting learner's basic needs and addressing these areas in more detail. The Solihull Approach (2015) is a method that could be considered for use with restorative clinical supervision, especially for tackling conflict resolution or challenging behaviours. It underpins and supports different models of therapy, focusing on the structure of good relationships, so that techniques can be extra effective. It also uses concepts of containment, reciprocity and behaviour management as the basis for developing relationships. Although its focus is on relationships between parents and children, it could be used in clinical supervision to support the PMA, who could use containment to allow emotions to be processed in a calm manner, providing capacity to think. Suitable behaviour management strategies are developed from an awareness of feelings, which is part of being a successful PMA. While being aware of potential barriers, PMAs should strive to foster a worthy relationship with those they represent, as this will enhance the outcome of restorative clinical supervision.

Like all relationships, the supervisory one requires consideration and responsiveness. Rogers (1951) offers a useful description of the non-directive methodology used for this style of supervision. Schon (1987: 92) likens Rogers to Socrates:

‘Functions as a paradoxical teacher who does not teach but serves as gadfly and midwife to others' self-discovery—provoking in his interlocutors.’

Change management

Since its introduction at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, the role of the PMA is becoming more recognised for the important benefits it can offer. It was noted locally that some midwives responded with caution (personal correspondence, 2018), which could be due to a lack of awareness about the change. It was also noted, from further investigation (personal correspondence, 2018), that some midwives were previously unwilling or reluctant to engage with clinical supervision. NHS Education for Scotland (2017) examined how time pressures and staffing levels could affect resistance to change and discussed why staff find it difficult to accept change in the workplace. Being responsive to the engagement of staff with the implementation of the A-EQUIP could be a driver towards acceptance (NHS England, 2017); however, this will require further evaluation in the future. Providing guidance to staff and explaining the benefits that restorative clinical supervision has to offer could lead to staff acknowledgement of the benefits and willingness to participate in sessions (NHS Education for Scotland, 2017). Transformational leadership, in which leaders inspire positive changes in those who follow (Cherry, 2018), can assist when implementing change and when inspiring and motivating staff (Fischer, 2017). Research evidence clearly shows that groups led by transformational leaders have higher levels of performance and satisfaction than groups led by other types of leaders (Riggio, 2009). Adopting leadership styles that involve networking, engagement and compassion could improve connections and the development of emotional intelligence (Wallbank, 2014).

It is suggested in the research used throughout this reflection that restorative clinical supervision can aid personal positivity and clarify change, therefore increasing the ability to feel more at ease with managing certain situations, and reducing stress and burnout (Pettit and Stephen, 2015). This evidence has been used locally to reassure and improve midwives' understanding of the benefits of restorative clinical supervision and the potential for quality improvement.

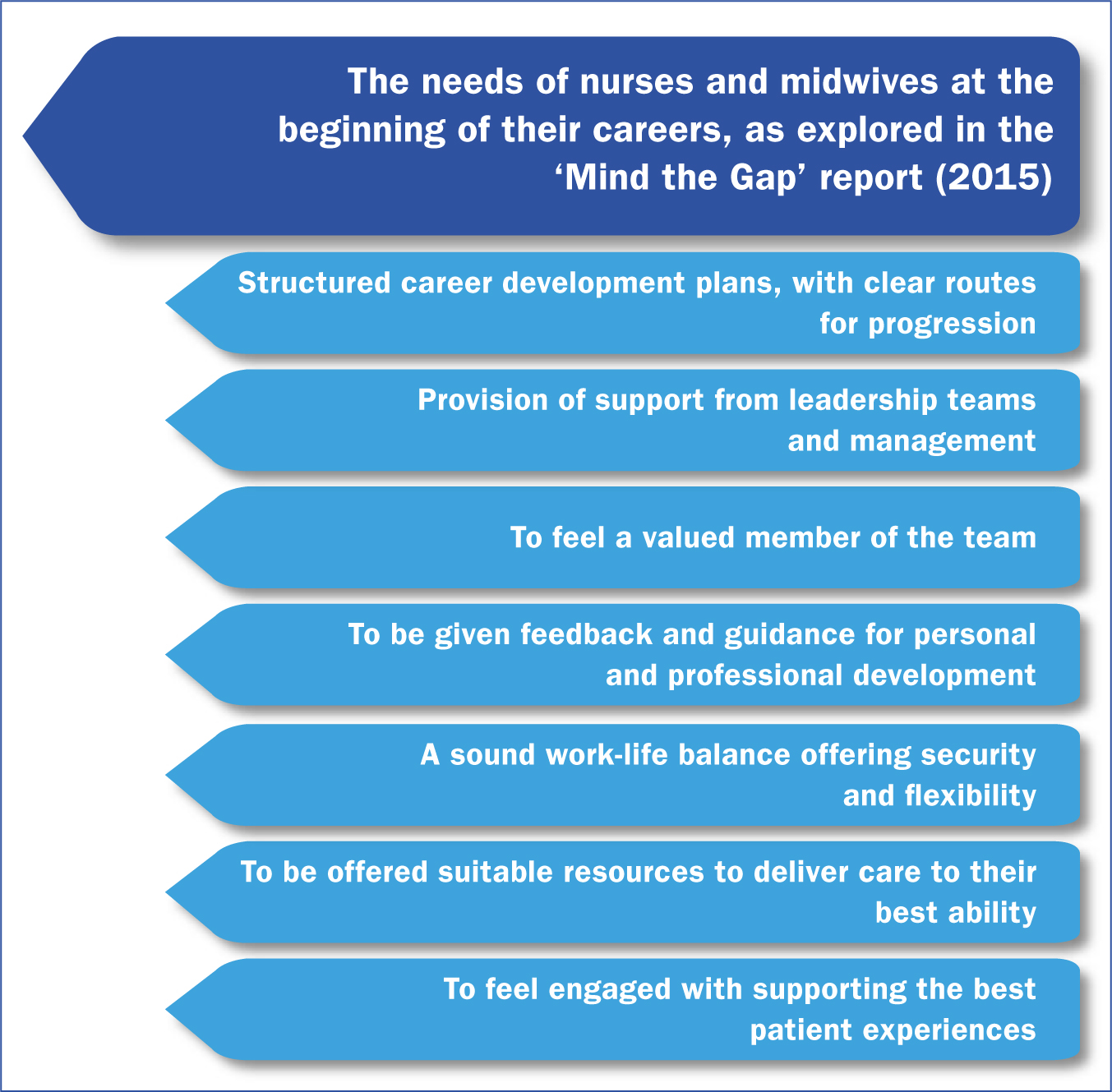

Overview for pilot sessions

Restorative clinical supervision sessions were initiated with newly qualified midwives, as the local group of PMAs acknowledged that these midwives of the future were pivotal members of the team; and that those with experience should guide and positively influence changes in staff culture (Sterry, 2018). The Mind the Gap report (Jones et al, 2015) recognised that newly qualified midwives can find the transition from a student to a registrant difficult, and detailed seven aspects of their requirements post-qualification (Figure 4). These aspects reinforce how the A-EQUIP model can be valuable. Introducing sessions with this staff group seemed most appropriate, with the added consideration that they would not have previous knowledge, preconceptions or experiences of engagement with supervisors of midwives. It was envisaged that action learning sets (Hawkins and Smith, 2013) would evolve from the restorative clinical supervision sessions provided. Action learning sets have been found to be extremely valuable for continued support in groups.

The session

The restorative clinical supervision session was run by two PMAs (previously supervisors of midwives) and attended by five newly qualified midwives. It was underpinned by a verbally agreed contract between the PMAs and the group, and the author participated as a student PMA. Stacey et al (2018) provide a referenced guide for leading restorative clinical supervision, which also offers direction when planning sessions. An explanation of restorative clinical supervision was given at the beginning of the session. This is important for setting parameters, which explains to participants the degree of safety found in a confidential and non-judgmental space, where provision is offered for discussion and reflection (Stacey et al, 2018).

The session was not documented, nor was a register taken. Previously, supervisors of midwives were required to document any meeting, one of the many differences between the supervisor of midwives and PMA roles. Because of these differences, bridging programmes have been provided for supervisors of midwives to transfer and develop skills. Restorative clinical supervision sessions should be led by PMAs who have undertaken a bridging course or the full programme (NHS England, 2017).

The time and length of sessions is important and should be clarified at the start. Providing midwives with the time to reflect on experiences that have affected them can improve their capacity to review the care that they deliver to women and the decisions they make (Wallbank, 2013). However, without a timeframe to provide structure, the session could be prolonged. Els van Ooijen (2003) explains the importance of developing a ‘working agreement’ when providing clinical supervision. Three steps (‘what?’, ‘how?’ and ‘what now?’) are discussed in detail and could be used to guide the questions that are asked in order to mutually agree conditions during sessions of restorative clinical supervision.

The session ran for 1 hour. The midwives spoke for the majority of the time with some small gaps throughout, in which the PMAs waited for them to continue or invited further discussion using inquiry-based questions (Els van Ooijen, 2003), based on Hammond's (2013) ongoing research into the underlying theory behind appreciative enquiry and its use as an approach to change. The difference between the PMA and supervisor of midwives role was acknowledged and it took great concentration not to interject with thoughts or opinions but instead to use appreciative enquiry to allow further reflection. Although moments of silence during this session were minimal, there was an understanding that it was acceptable.

The discussion

The discussion was mainly work-related, with reference to feeling unsupported by certain practitioners. In Hunter and Warren's study (2013), participants identified instances when they thought midwives were more predisposed to workplace adversity, such as when newly qualified or providing care in challenging cases. In these discussions, however, thoughts regarding teamwork and how the multidisciplinary team affected these interactions were considered. Positive interactions with team members were mentioned as well as exciting developments for self-progression. Three midwives expressed experiences of stress and working in a pressured environment and one midwife became visibly upset after recalling the recent experience of an obstetric emergency. Another had encountered pressure from a colleague to complete tasks outside of her scope of practice. One midwife provided an example of encountering increased expectations for qualification level, which left her questioning her chosen career pathway. Despite the difficulties of these experiences, participants seemed to be at ease with sharing within the group, as they spoke freely and without hesitation. This confirmed the session as a ‘safe space’, without which participants may not have felt able to disclose such experiences. Proctor (2004) explains the private relationship between the ‘client’ and the ‘supervisor’ as the supervisor encouraging the reflection process but not demanding detail. Restorative clinical supervision provides the space for midwives to use ‘transference’ as a coping mechanism towards reflecting and understanding the experiences they face (Dryden and Reeves, 2008). In this context, transference relates to the way in which people understand one another and form relationships with one another (Dombeck, 2019). The PMA provides challenge by way of appreciative enquiry in a style that guides further thought for learning and growth. The discussion focuses on the identification of what works and how this can grow or be used, rather than contemplating negativity around certain experiences (Stacey et al, 2018). In reflecting on the experiences shared and the discussions that took place during the group session, as anticipated, resilience was highlighted as a major factor in midwives' coping strategies. Discussion of long-term strategies for enhancing resilience took place, which included recognising warning signs and anticipating what action they might take to avoid or reduce stress and adversity in the future. Sessions came to a natural close.

Why resilience?

Some of the research discussed in this reflection tells us that the emotional demand on midwives can contribute to increased levels of stress, rates of sickness, attrition and low morale in the workplace (Kirkham, 1999; RCM, 2016; Jones et al, 2015; NHS England, 2017; Sterry, 2018). Challenges in the workplace also led to concerns regarding quality of care for women and seems to be a common theme in the research cited in this article. It is clear that careful consideration of how best to support midwives in preparation for the pressures they face is required. Hunter and Warren (2013) indicated that the emotional skills that midwives use can be unrecognised and unappreciated. The emotional challenges that midwives face is further increased by the rising birthrate, larger numbers of women with complex needs and the national shortage of midwives (RCM, 2016). In 2012, the Government advised that it would strive to increase the number of qualified nurses and midwives (Department of Health and Social Care, 2012). This expansion of UK professions is resulting in an increased number of students, the management of which is being reflected in the new NMC standards for education and training in nursing and midwifery (NMC, 2018a; 2018b).

‘Despite of all of these challenges, the majority of midwives prosper and succeed in the workplace. This positivity and demonstration of professional resilience indicates that if midwives are equipped, they will likely have the ability to adapt, grow and flourish in challenging environments’

This pressure on staff is exacerbated by workplace adversity and yet, despite of all of these challenges, the majority of midwives prosper and succeed in the workplace. This positivity and demonstration of professional resilience indicates that if midwives are equipped, they will likely have the ability to adapt, grow and flourish in challenging environments (Hunter and Warren, 2013). Encouraging staff to consider their abilities, to be willing to change and to think about the ways they can support quality improvement is a key aspect of the PMA role and can be used in restorative clinical supervision. The ‘Plan, Do, Study, Act’ (PDSA) model (NHS Improvement, 2018) can provide staff with a useful tool to guide a quality improvement initiative. Restorative clinical supervision can be used as part of an alternative leadership focus, supporting staff in a variety of ways and providing opportunities for reflection, with an emphasis on quality improvement, not only by tackling stressors and increasing resilience, but also to ensuring excellence in care (Wallbank, 2013). Giving midwives the opportunity to contribute actively in audit, research and/or other quality improvement activities, not necessarily in a clinical setting, will help to address service improvement requirements and job satisfaction (NHS England, 2017). Involvement in the review and evaluation of cases during risk, guideline and governance meetings embeds the lessons from incidents in practice, in order to implement findings and providing reassurance and answers to service users.

Much of the research on restorative clinical supervision has been undertaken in other professions and further studies are required to provide additional investigation into the understanding of resilience in midwifery.

Some of the challenges to resilience that midwives face have been categorised in Hunter and Warren's study (2013). Resilience strategies are usually developed during midwives' careers as a result of experience (Wallbank, 2014). Midwives constantly juggle different emotionally charged situations, life and death experiences in which professionalism and accountability are required at all times. This can prove challenging, and Hunter and Warren further explore the effect this has on personal resilience incorporating the balance of both work and personal circumstances. This juggle contributes to their own progression of endurance, leading to resilience. Restorative clinical supervision, guided by a PMA, should lead midwives to use their previous personal and professional experiences to develop their attributes for solution-focused discussion of their own identified needs.

During a restorative clinical supervision session, the PMA supports and empowers colleagues. Resilience is likely to have already been learnt through experience; however, it can also be developed. The implications of teaching resilience to manage stress and burnout should be considered as we look for ways to instil resilience at earlier stages in midwifery (such as during pre-registration training). A pedagogical teaching approach is considered by Grafton et al (2010), who also discuss the difficulty of teaching resilience. The effectiveness of teaching resilience theory to student midwives requires further investigation (Hunter and Warren, 2013). Wallbank (2013) recognises that evaluating the effectiveness of restorative clinical supervision overall requires wider study, but nevertheless provides evidence for its importance in today's demanding workplace.

Evaluation of sessions

Trusts can anticipate that the Care Quality Commission (CQC) will deem it important to collate evidence to demonstrate that A-EQUIP can provide staff with the support that they require. Constant reflection and evaluation of interventions can lead to well-led sessions and can in turn develop PMAs' skills in this area (Els van Ooijen, 2003). Evidence could be collected by use of activity forms; the promotion of the PMA role on mandatory training; representation at guidelines, risk and governance meetings or by participating with maternity voices groups. Other examples include collating evidence of development and upkeep of display boards; holding regular PMA meetings; recording when restorative clinical supervision is provided and conducting an ongoing review of key performance indicators (known to the Trust Board). Sharing good practice and celebrating success of quality improvements can also develop a valued, positive and resilient workforce (Sterry, 2018). While positive verbal evaluation is reassuring, it is important to evaluate supervision sessions effectively and to note the potential barriers that could present in future sessions. It would be reassuring to know that the midwives at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust are benefitting from the sessions provided, and so further evaluation will be sought by use of the professional quality of life questionnaire (Hudnall Stamm, 2010).

Conclusion

Considering the emotional and physiological stress on the NHS workforce, investing in resilience is a cost-effective and positive step towards protective strategies for staff (Sterry, 2018). If staff resist adversity and are responsive in a positive way, we can be assured that they are displaying optimal resilience. The research so far suggests that offering support through restorative clinical supervision will develop and encourage resilience. Restorative clinical supervision also offers support to midwives in the form of a positive supervisory relationship. If PMAs and midwives work together in a safe space, restoration can take place and resilience will ensue. The research mentioned in this reflection highlights the importance of tackling the support and development needs of health professionals through clinical supervision and reflective practice. Evidence clearly identifies that staff who feel supported, valued and developed are more likely to provide a valuable contribution to outcomes for women and their families. At the core of midwife is their love of midwifery practice, which can sometimes be marred by professional and personal strains. At University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, it is expected that restorative clinical supervision will be offered to midwives at different stages of their careers and in different clinical roles. The PMA role can involve the development of interventions, the promotion of resilience and the safeguarding of exceptional care for women.