Working in line with the Nursing and Midwifery Council's ([NMC], 2018) code of conduct, midwives are expected to be with woman, yet the welfare of the baby must remain paramount in this, as directed by the Children Act of 1989 and 2004. Currently, care applications for babies to be taken into care are at a national high (Macfarlane, 2018). In England, between 2007–2017, 16 849 babies under one week old were subjects of local authority care proceedings (Broadhurst et al, 2018). This is concerning, as life outcomes can be significantly impaired for those children who are taken into care (UK Government, 2017). Yet in offering evidence-based support and interventions for vulnerable women and families, some babies could be prevented from being taken into care (McCracken et al, 2017). Several strong predictors of having one's first baby taken into care at birth have been identified. These include substance use, the mother being in care at the time of her baby's birth, mental ill health, lack of antenatal maternity care and the presence of a developmental disability (Wall-Wieler et al, 2018). Yet again, these risk factors could be mitigated with the use of appropriate interventions.

Consideration must also be given to the emotional trauma experienced by the mother who is separated from her baby, as these women are more likely to suffer from depression, problem substance use and mental illness, even when compared to women who've experienced a baby bereavement (Kenny, 2017). This may be because of the increased social support and sympathy provided to a bereaved mother as opposed to the stigma associated with child removal. In any case, the rise in care cases places extra pressure on the care system and support services, resulting in cost implications for society. As such, there is a need to support childbearing women who are at risk of having their baby removed at birth more effectively to improve outcomes for the whole family and pressured services. Moreover, the more knowledge a midwife has in relation to removing babies at birth, the better his or her ability may be to professionally make sense of it, mitigate the effects of moral distress and demonstrate resilience (Marsh et al, 2019). Consequently, for a target audience of midwives, the aims of this review were as follows:

Aims

- To explore the contemporary literature in relation to supporting childbearing women at risk of having their baby removed from them at birth

- To identify effective and contemporary therapeutic mechanisms and interventions which midwives could draw from, to facilitate better support for childbearing women at risk of having their baby removed from them at birth.

Methods

A review of the literature was conducted in the Autumn of 2019. The exclusion and inclusion criteria applied to this review is presented in Table 1. Contemporary research articles, presenting primary evidence in relation to cohorts displaying strong predictors of having their baby taken into care at birth such as substance use, being in care at the time of the baby's birth, mental ill health, lack of antenatal maternity care and the presence of a developmental disability were pursued (Wall-Wieler et al, 2018). As some women with these risk factors are also known often to have complex histories, including experience of childhood trauma, domestic violence and abuse, and typically negative models for parenting (Pajulo et al, 2006) along with involvement with the criminal justice system (Phillips and Gleeson, 2007), relevant evidence pertaining to these issues was also sought for inclusion.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Justification | Exclusion | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Written in English language | Author limitations | Books | Unlikely to be current and may offer bias |

| Must involve removal from birth and include an intervention | To ensure focus | Literature reviews | To prevent duplication and bias |

| Published anytime since the beginning of 2016 | Child protection is dynamic and therefore evidence needs to be current | Does not include health intervention or social intervention in pregnancy | Does not meet targeted audiences needs |

| Peer-reviewed | To ensure quality and non-bias | Women/families with vulnerabilities not related to child protection | Not focused on aims |

| Must be related to child protection | Topical to question and to ensure focus | Involves maternity services but outside of remit | To ensure recommendations of findings are suitable for application in practice |

The databases which were employed for this task included NELSON, the British Nursing Index, Science Direct, CINHAL, SAGE, Scie, Amed and Assia. The search terms used related to family, care orders, safeguarding, child protection, birth, child abuse, pre-birth assessment, babies and women along with support, obstetric and maternity services. The decision to include articles was based upon their relevance to the subject area and ability to address the aims of this review. Selected articles which met the inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed and reported on primary data published anytime since the beginning of 2016.

The review team primarily critiqued articles deemed broadly relevant and screened them to ensure that the final selected studies remained focussed upon meeting the aims of this review. Subsequently, in order to establish initial themes arising from the data presented within the articles selected for inclusion, a summary table was created. This detailed the main features and critique of each article selected for inclusion. Following this process of summarisation, themes of relevance were annotated, collated and categorised under thematic headings in a series of refinements.

Findings

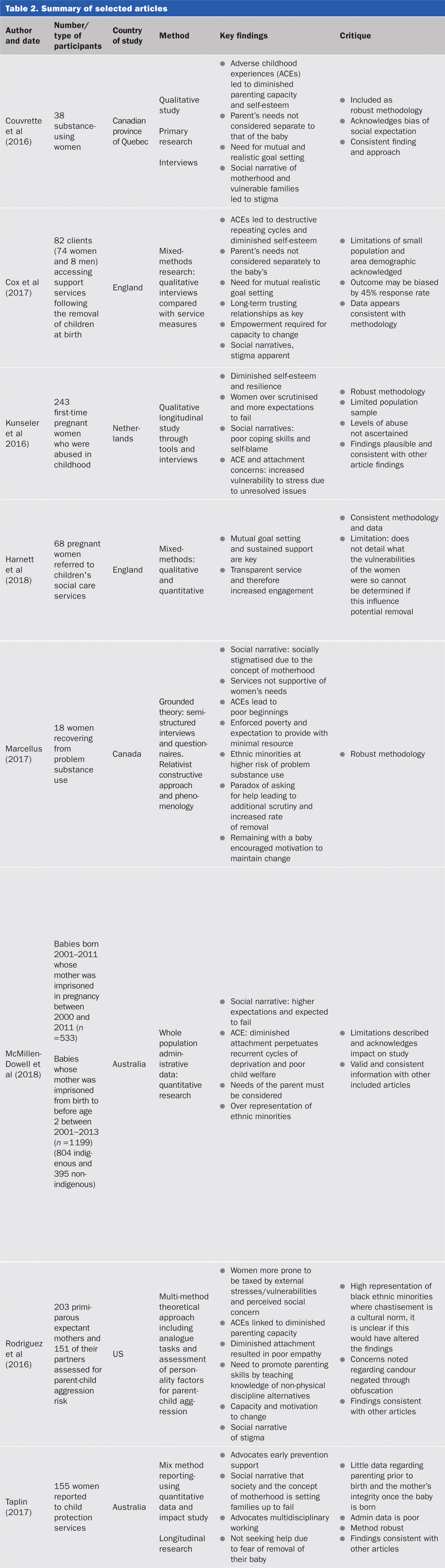

A total of eight articles were selected for inclusion. The studies reported on were conducted in Canada (Couvrette et al, 2016; Marcellus, 2017), Australia (Taplin, 2017; McMillen-Dowell et al, 2018), England (Cox et al, 2017; Harnett et at, 2018), the Netherlands (Kunseler et al, 2016) and the US (Rodriguez et al, 2016). They included a total of 2 539 participants. A more detailed summary of these studies along with a critique of each article is presented in Table 2. Ethical approval was granted for all studies included.

Table 2. Summary of selected articles

Table 2. Summary of selected articles Table 2. Summary of selected articles

| Author and date | Number/type of participants | Country of study | Method | Key findings | Critique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couvrette et al (2016) | 38 substance-using women | Canadian province of Quebec | Qualitative studyPrimary researchInterviews |

|

|

| Cox et al (2017) | 82 clients (74 women and 8 men) accessing support services following the removal of children at birth | England | Mixed-methods research: qualitative interviews compared with service measures |

|

|

| Kunseler et al 2016) | 243 first-time pregnant women who were abused in childhood | Nether-lands | Qualitative longitudinal study through tools and interviews |

|

|

| Harnett et al (2018) | 68 pregnant women referred to children's social care services | England | Mixed-methods: qualitative and quantitative |

|

|

| Marcellus (2017) | 18 women recovering from problem substance use | Canada | Grounded theory: semi-structured interviews and question-naires. Relativist constructive approach and phenomenology |

|

|

| McMillen-Dowell et al (2018) | Babies born 2001–2011 whose mother was imprisoned in pregnancy between 2000 and 2011 (n = 533)Babies whose mother was imprisoned from birth to before age 2 between 2001−2013 (n = 1 199) (804 indigenous and 395 non-indigenous) | Australia | Whole population administrative data: quantitative research |

|

|

| Rodriguez et al (2016) | 203 primiparous expectant mothers and 151 of their partners assessed for parent-child aggression risk | US | Multi-method theoretical approach including analogue tasks and assessment of personality factors for parent-child agg-ression |

|

|

| Taplin (2017) | 155 women reported to child protection services | Australia | Mix method reporting-using quantitative data and impact studyLongitudinal research |

|

|

Findings were categorised into three overarching themes comprising social narratives, adverse childhood experiences and the needs of the adult. Seven sub-themes were also identified. In the following sections, themes have been separated for clarity. However, the themes themselves can be considered composite in their relationships.

Theme one: social narratives

The articles of Couvrette et al (2016), Cox et al (2017), Kunseler (2016), Taplin (2017), McMillen-Dowell et al (2018), Marcellus (2017) and Rodriguez et al (2016) all alluded to the concerns that society has in regard to vulnerable women such as those under consideration here. Largely, findings suggest that the concept of motherhood in this context may have already set women up to fail (Couvrette et al, 2016). Such conclusions may support some midwives' ability to professionally make sense of how those at risk are perceived and may be affected by social narratives.

Sub-theme: the paradox of help-seeking, fear and stigma

‘The societal shame that they feel is phenomenal and that does further impede them from making any step forward. You just can't shrug that off (Cox et al, 2017).’ Kunseler (2016) discussed the high expectations associated with women receiving interventions from social care. Marcellus (2017) reported that women who are supported by social care also have significant socio-structural challenges in maintaining an acceptable home environment in order to support their children effectively. For example, women who are in the childcare system were found to have higher incidence of having children with special educational needs.

Some women in deprived situations were also found to be required to do more with less, and yet achieve the same progress as those without such barriers in reaching a suitable home environment (Marcellus, 2017). Paradoxically, some women may also fear and/or avoid accessing antenatal care due to narratives they hear in relation to child removal (Taplin, 2017). This dissuasion to engage with services may in turn sabotage the chances of creating the stable family life they are expected to sustain. As such, it will be important for midwives to address and dispel such fears in pursuit of more effective engagement with services.

Sub-theme: childbearing as a motivator for change

Despite the social stigma associated with families in the child protection system, Couvrette et al (2016) noted that many women, especially those who were in recovery from problem substance use found the responsibility and social expectations of motherhood offered a strong motivation to make the changes required to adequately parent their children. In becoming a mother, some women with previous substance use problems were also able to re-establish a sense of self that had been lost (Marcellus, 2017). In this sense, Marcellus (2017) described motherhood as a form of social capital which could pay for a conventional life and help build resilience in recovery. Yet Taplin (2017) discussed concerns that babies born into such disadvantaged demographic populations may lack the capacity to change due to a potential increased incidence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. In any case, it will be important for midwives to recognise that childbearing can act as a key motivator for change.

Midwives were found to be determined to prevent removals where they could (Cox et al, 2017). Moreover, during custodial sentences in the criminal justice system, where maternity care is regulated and inmates have access to basic nutrition and healthcare, pregnant women and their families were found to thrive (McMillen-Dowell, 2018). Seemingly, motivation for change involves all parties and can act as a powerful catalyst in some scenarios. In recognising this, midwives could usefully harness this opportunity in women's lives to champion sustained rehabilitation and recovery with optimism.

Sub-theme: inequalities in ethnic minority groups

Consistently throughout the selected articles, there are specific references made to the disadvantaged families of ethnic minorities. The articles of Talpin (2017), McMillen-Dowell (2018), Marcellus (2017) and Rodriguez et al (2016) all report an over representation of minority groups within the social care system in Canada, America and Australia. Here, some minority families felt that they were subject to false accusations, racism, systematic scrutiny and that they had diminished rights when involved with legal proceedings regarding their children which resulted in feelings of powerlessness and persecution (Marcellus, 2017). In overcoming such inequalities, these families may enjoy improved outcomes overall.

Theme two: adverse childhood experiences

Couvrette et al (2016), Cox et al (2017), Kunseler et al (2016), Marcellus (2017), McMillian-Dowell et al (2018) and Talpin (2017) found adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), along with patterns of diminished attachment and self-esteem to be intrinsically linked. It is unclear which precedes which, however the impact of each theme appears to have an adverse effect on the other. Specifically, articles identified within this review describe the impact of the women's own ACEs having shaped the women's parenting styles and feelings of resilience, worth or self-esteem (Couvrette et al, 2016; Kunseler et al, 2016; Cox et al, 2017; Marcellus, 2017; McMillian-Dowell et al, 2018). Often, ACEs led to diminished parenting capacity and self-esteem (Couvrette et al, 2016). In understanding these links, midwives may be better able to identify and support those affected.

Sub-theme: capacity for change and self-esteem

Articles by Kunseler et al (2016) and Rodriquez et al (2016) suggest that low self-esteem could be a factor in parents with decreased empathy. Such factors were also reported to increase emotional responses to children in distress (Kunseler et al, 2016), and physical chastisement (Rodriquez et al, 2016), potentially leading to further adverse childhood experiences. Additionally, in the study by Rodriquez et al (2016), the father was the perpetrator in half of all cases of child chastisement, yet the focus primarily remained with women to initiate change. This expectation may reinforce social stigmas around the role of women in families and their capacity to change overall.

Marcellus (2017) found that for women facing recovery from problem substance use, restoring a sense of self was imperative in ‘holding it together’ as a parent. Here, women felt a sense of pride in their capacity to maintain a functioning family home, despite their challenges and the difficulties that their disadvantaged families faced (Marcellus, 2017). As such, enhancing women's self-esteem may be a key factor in increasing their capacity for change in this context.

Theme three: the needs of the adult

Cox et al (2017), Harnett et al (2018), Taplin (2017), Marcellus (2017), Couvrette et al (2016) and Rodriquez et al (2016) all recognise that the needs of the adult must be recognised and met as they are integral to positive behaviour change in this context. Themes around goal setting, the development of meaningful relationships and early intervention featured throughout the literature identified for inclusion.

Sub-theme: mutual and realistic goal setting

Mutual and realistic goal setting was found to be therapeutic for childbearing women at risk of having their baby removed from them at birth (Couvrette et al; 2016; Cox et al, 2017; Harnett et al, 2018). Cox et al (2017) in particular found that the best results were achieved when women were able to set their own goals rather than being provided with an overwhelming list of unachievable goals. Mothers who use substances and identify as being ‘deviant’ specifically felt more able to change once they believed that goals in relation to their children were attainable (Couvrette et al, 2016). It was also important for women to take ownership of their goals, especially when facing the stigma of society (Cox et al, 2017). Evidently, supporting women to have autonomy in their decision-making empowers them in their goal setting and improves their self-esteem (Harnett et al, 2018). Furthermore, in the work of Cox et al (2017), it was reported that women who were empowered and supported to set goals also developed more empathy and self-awareness. Interestingly, these were qualities that Rodriquez et al (2016) also found to be factors in preventing child parent aggression. Consequently, midwives could usefully engage childbearing women at risk of having their baby removed from them at birth in mutual and realistic goal setting in this context.

Sub-theme: professional relationships

Cox et al (2017), Harnett et al (2018), Taplin (2017) and Marcellus (2017) noted that women are likely to have a skeptical view towards practitioners from social care. This is mostly evident where social care and safeguarding services have been involved in the removal of a previous child. Harnett et al (2018) also noted that prior to commencing innovative intervention programmes, some women were anxious and defensive due to their perception of services. In response, the above authors along with Couvrette et al (2016) press on the importance of support workers developing a strong, positive and supportive relationship with families. Specifically, Cox et al (2017) suggest that there are four main relationship themes required for recovery: respect, choice, empathy and critical friendship. Interestingly, Cox et al (2017) also found that creating a positive relationship with a support worker benefited all the relationships in participants' lives, allowing for additional support from the wider circle of friends and family.

Some women felt better supported by agencies alternative to social care and safeguarding services (Marcellus, 2017). For example, in the work of Cox et al (2017), 50% of participants felt that they had a good or excellent relationship with their support worker and 63% felt they had similar relationships with other agencies. Yet in relation to maternity services, Taplin (2017) noted the challenge in that pregnant women have a shortened time span to develop trusting relationships and to meet the required targets that reassure the baby's safety at birth. Moreover, women may be referred to support services later in pregnancy, reducing this window further. As such, midwives face the challenge of working quickly and early on to build such trusting relationships in pursuit of optimal outcomes for these families.

Sub-theme: early and sustained interventions

Rodriguez et al (2016), Marcellus (2017) and Taplin (2017) all suggested the need for early and sustained interventions for families which are supportive of women's individual needs. All directed the success of home visiting and residential programmes for women to help achieve their needs in partnership with multidisciplinary teams of professionals. Yet unfortunately, Taplin (2017) reported that interventions usually occurred in the last trimester of pregnancy or a short time after, where most of the babies in these cases were removed within a hundred days of birth. Consequently, the challenge here will be to engage women in such interventions as early as possible. Ensuring that services are transparent may increase engagement with services overall (Harnett et al, 2018).

All selected studies noted that blended programmes which include community support services were of most value to women, especially when combined with a strengths-based perspective where there is greater emphasis placed on strength and capacity rather than deficit-based constructions (Marcellus, 2017). Rodriguez et al (2016) specifically made a key recommendation that the best way to support women would be to endorse the creation of an integrated maternity care model including relevant agencies to meet the needs of the woman in this context. The promotion of parenting skills, teaching knowledge of non-physical discipline alternatives was also recommended where childbearing women have access to support programmes over an extended period of time (Rodriguez et al, 2016). These findings may inform the development and enhancement of both new and existing support services as progress continues to be made in this area.

Discussion

This review of the literature has explored contemporary evidence in relation to supporting childbearing women at risk of having their baby removed from them at birth. It has also identified effective and contemporary therapeutic mechanisms and interventions which midwives could draw on to facilitate better support for women at risk of having their baby removed from them at birth. Three themes and seven sub-themes recount the recent evidence base in relation to social narratives, adverse childhood experiences and the needs of the adult in providing effective support to these women and their families. Here, mutual, and realistic goal setting along with the development of strong professional relationships and early and sustained interventions appear to be most effective in supporting the vulnerable cohorts identified within the literature presented. These findings emulate those of earlier studies, where the development of strong professional relationships (Harvey et al, 2015), along with realistic goal setting (Curry et al, 2006) have also been cited as key in improving outcomes in this context.

Findings presented here also reveal how society may have a conventional view of what a mother and family should be. As such, any deviation from these socially accepted norms may result in mothers being considered failures. This, along with evidence of other social stigmas, biases and inequalities may in turn have further fuelled existing beliefs that social care and safeguarding services are simply a surveillance service looking to remove children from their parents (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009; Broadhurst et al, 2013; Cox et al, 2016; Sharps et al, 2016).

Indeed, pregnancy was found to be a motivator and opportunity for change (Couvrette et al, 2016), yet due to such mistrust of services, some vulnerable women were reportedly reluctant to seek help (Taplin, 2017). This phenomenon has also been reported on elsewhere (Tsantefski et al, 2011). Additionally, it has been suggested that as the families in question are typically disadvantaged, they may not be viewed by society to have capacity to achieve acceptable change in order to parent their child effectively (Marcellus, 2017; Taplin, 2017; McMillin-Dowell, 2018). This appears to be due to their perceived lack of resources to meet even the basics of their own needs and subsequently that of their children (Marcellus, 2017; Talpin, 2017; Harnett et al, 2018). Similar findings have been presented elsewhere (Lewin et al, 2017). These societal beliefs may prove to be further barriers in seeking and seizing opportunities for support. Future support services could usefully act to dispel such mistruths and distrust.

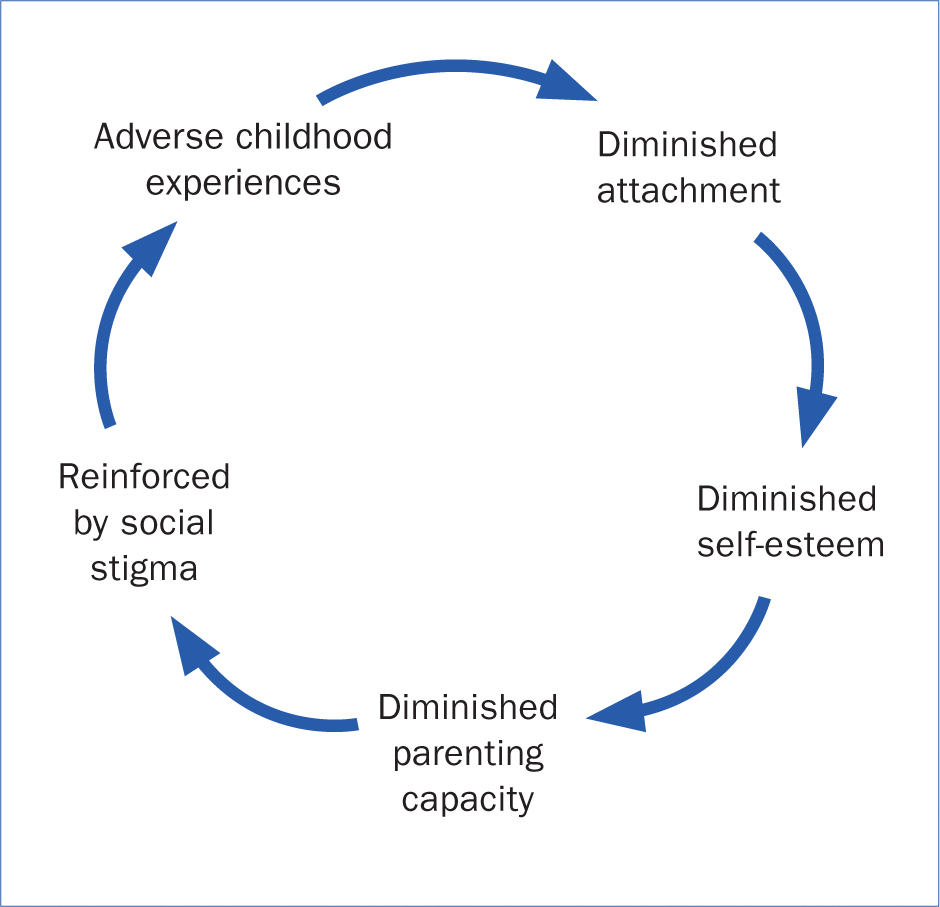

A clear consequence of their disadvantaged lives is that some participants within these studies have been exposed to ACEs (Courvrette et al, 2016; Kunseler et al, 2016; Rodriquez et al, 2016; Marcellus, 2017; McMillen-Dowell et al, 2018). Some of these have in turn led to diminished attachment with future children (Corvette et al, 2016; Kunseler et al, 2016; Rodriquez et al, 2016; McMillen-Dowell et al, 2018). The parent's resulting poor self-esteem and attachment can then be reinforced and further diminish parenting capacity, subsequently increasing the likelihood of further ACEs (Couvrette et al, 2016; Kunseler et al, 2016; Rodriquez et al 2016; Cox et al, 2017; Marcellus, 2017; McMillian-Dowell et al, 2018). These consequences can then be further reinforced by social stigma (Courvrette et al 2016; Rodriquez et al, 2016; Cox et al, 2017; Marcellus, 2017). Similar findings have been presented elsewhere (Iyengar et al, 2014; Young et al, 2017). Uniquely, using the themes presented within this review, we have been able to model this cycle as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Cycle of maltreatment model

Figure 1. Cycle of maltreatment model

The role of the midwife

Named midwives for safeguarding babies have a key role to play in integrated safeguarding teams, working to progress national, regional and local safeguarding agendas. Yet there are five essential functions of all named professionals in child safeguarding. These involve interagency cooperation, training, monitoring, supervision and the leading of safeguarding activities at an organisational level (Green, 2019).

The importance of this role to society cannot be underestimated in light of the increased understanding of the negative effect the removal of a child can have on both parent and child, and the integral role this has in the repeating cycle of troubled families (Widom et al, 2015). Yet it is the role of every midwife, in partnership with other organisations and professionals, to monitor the health and well-being of both the pregnant woman and her unborn baby (Department for Education, 2014). This includes identifying risk factors which could impact upon the ability of parents to care for their baby safely in complex social situations which some midwives may not be adequately prepared for (Halsall and Marks-Maran, 2014). Ultimately, to preserve safety, all midwives are guided by the NMC code in this regard. Yet further education in this area could also mitigate some of the barriers to women seeking support from safeguarding services presented within this review.

Midwives who care for women whose babies are removed at birth can experience high levels of moral distress and report this experience as being one of the most distressing in contemporary clinical practice (Marsh et al, 2019). Yet as increased knowledge in this area can mitigate some of the negative effects of moral distress such as anger, anxiety, guilt and frustration, further education along with the findings presented here may go some way to supporting midwives in this area of clinical practice too. In any case, as this review only yielded eight studies in total, further research could usefully inform a richer provision of research inspired teaching and training in this area.

Conclusion

Midwives are well-placed to advocate for the needs of women. Pregnancy provides a key opportunity to support and educate vulnerable women in building healthy attachments to interrupt any destructive repeating cycles apparent. This review uniquely presents a model in relation to the cycle of maltreatment. This is a contemporary thematic cycle, representative of the eight articles reviewed. The findings and insights presented here may inform the development of future interventions designed to support women at risk of having their baby removed at birth more effectively.

Key points

- A contemporary thematic cycle of maltreatment model, representative of the eight articles reviewed is presented

- Findings point to the development of blended, early and sustained intervention services for vulnerable women and their families

- Goal setting and the development of strong professional relationships can be of great benefit to the lives of vulnerable women and their families

- Adverse childhood experiences play a key role in the quality of future parenting

- Social stigma, fear and inequalities remain key barriers to women seeking support from safeguarding services

CPD reflective questions

- What are some of the key barriers to women seeking support from safeguarding services?

- What are some of the needs of the adult in relation to safeguarding children?

- What inequalities currently exist for the participants included in this review?

- What challenges might midwives face in supporting women at risk of having their babies removed from them at birth?

- Can you identify some of the societal myths surrounding safeguarding services?