The past decade has seen significant, system-wide changes to the midwifery profession. These have arisen as a result of a number of public enquiries, commissioned reports, publications and policy documents: Maternity Matters (Department of Health, 2007), Midwifery 2020: Delivering Expectations (Chief Nursing Officers of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 2010), the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (2013) report into midwifery supervision and regulation, the report into midwifery regulation (The King's Fund, 2015), The Report of the Morecambe Bay Investigation (Kirkup, 2015) and Better Births (National Maternity Review, 2016). A recurring theme throughout these documents is the importance of professional midwifery leadership at a local, regional and national level. The purpose of this article is to explore this further, to gain insight into whether the system-wide changes that the profession has seen in recent years call for clearer definition of professional midwifery leadership roles in England, and a remodelling of where they are situated within provider organisations and at regional and national levels. The hope is that the findings from this review will contribute to organisational planning and restructuring to ensure that the priorities of midwifery care and maternity services are heard at the right level, that high quality, safe care is delivered and that outcomes are improved for mothers, their babies and their families.

In 2016, on commencing his role as Director of Leadership and Organisational Development with The King's Fund, Marcus Powell made the following observation:

‘Keeping things the same serves organisations well when the context within which they are operating does not change. However, when the context does change, it is essential that organisations have the reflexive capability to notice the changes and the ability to adapt, otherwise, like many bureaucratic organisations in the private sector, they will simply become irrelevant and disappear.’

For the purpose of this review, professional midwifery leadership is defined as the formal part of leadership—setting the vision (or the ‘why’) for midwifery and maternity services within an organisation; creating a process for achieving organisational goals and ambitions; and aligning people, processes, and policy with the infrastructure to achieve those organisational goals (Badshah, 2013).

Professional leadership should always be combined with personal leadership, which can be thought of as the behaviour that leaders display when they perform the responsibilities of professional leadership. This includes trust, due regard, honesty, integrity and compassion. These personal behaviours make a professional leader successful and will convey the professional message to the organisation (Badshah, 2013).

Background

In January 2015, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) made the historic decision to separate statutory supervision of midwives from legislation and to take complete control of midwifery regulation. During the Council meeting, the NMC accepted that they had a ‘moral responsibility’ to ensure that the support for midwives that was so valued in the statutory framework should continue in a new model of ‘non-statutory’ midwifery supervision. The question was asked by an observer as to how the NMC was going to be assured that professional midwifery leadership would be secured regionally and nationally when the regulatory changes came into force; the NMC accepted that this was a responsibility for the wider sector to share.

Changes to the nursing and midwifery legislation took place under Section 60 of the Health Act 1999 and on the 28 February 2017, the Draft Nursing and Midwifery (Amendment) Order 2017 was put before the House of Lords with an amendment to the motion moved by Lord Hunt of Kings Heath, stating:

‘This House regrets that the draft order abolishes the statutory midwifery committee; and calls on Her Majesty's Government to ensure that robust arrangements are in place to ensure the continuation of supportive clinical supervision and leadership for midwives.’

While Lord Hunt's amendment to the motion was withdrawn, an important debate followed and was captured in Hansard (2017) with Lord Hunt and Baroness Cumberlege expressing the following views:

‘There are some issues of the visibility of professional leadership of the midwifery profession which I worry about. We know that midwives are subsumed under nursing leadership, and that has some consequences when it comes to priorities and resources.’

‘Can my noble friend consider having a chief midwifery officer at the national level, with directors of midwifery within the NHS England regional teams? We need that leadership.’

‘Are midwives around the right table? […] the experience of the health service is that they are never around the table at all. This is the problem. Whether the meetings are at board level of an English NHS Trust, at the top level of the senior management of a regional office of NHS executive, at the Executive itself, or at the department, they are never there. The big problem of how we get midwifery input at those top levels is one that we are still struggling with.’

The debate in the House of Lords raised many questions about the profile of professional midwifery leadership in England, and its effect locally, regionally and nationally.

Methods

Access to an online survey was sent all 136 Heads of Midwifery and Directors of Midwifery in England between March and May 2017. The survey asked questions about the profile of midwifery leadership in their organisation to gain an understanding of the profile of midwifery leadership at a local, provider level. Of the 136 recipients, 89 responses were received, which was a 65% response rate.

In addition, 17 one-to-one meetings were conducted with senior NHS professionals, including chief executives from the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and Royal College of Midwives (RCM); politicians (n=1) and members of the House of Lords (n=2); and the president of the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM). Consistent themes were explored with all interviewees.

Survey results

Titles

To gain a greater understanding of the titles used for the most senior midwife in provider organisations, the respondents were asked to state their title. Results are shown in Table 1.

| Options | Responses n (%) |

|---|---|

| Head of Midwifery | 50 (56.2) |

| Director of Midwifery | 15 (16.9) |

| Other (please specify) | 24 (27.0) |

The title ‘Head of Midwifery’ was the most common title used in England (n=50; 56.2%); however, there was a lack of consistency across the country, with a variety of other titles being used.

For the most part, the ‘Director of Midwifery’ title was used in large tertiary referral units, or in roles where there were additional responsibilities, such as gynaecology or reproductive health.

The RCM report, Directors of Midwifery in the Modern NHS (RCM, 2003), highlighted the importance of the Director of Midwifery role and stated that it was essential for maternity services to incorporate a more strategic and policy-influencing role. This is to ensure that maternity services are able to meet the Government's ambition for maternity and child healthcare.

This survey suggests that the RCM report has had minimal influence in increasing the number of Director of Midwifery roles in England. The survey could also point to a reluctance of provider organisations to consider the significant benefits to incorporating a more strategic and influential role at director level. This is replicated at regional and national level, where there are no Director of Midwifery roles.

Feedback received from the one-to-one meetings reflected a general agreement that the most senior midwifery role in a provider organisation should be that of a Director of Midwifery, who has direct access to the Trust Board on matters relating to maternity services. It was apparent from the survey that Trusts might include other portfolios such as women's services or paediatrics in the role. Some large Trusts with a number of site-specific maternity services have a Director of Midwifery with Heads of Midwifery on each site.

Remuneration

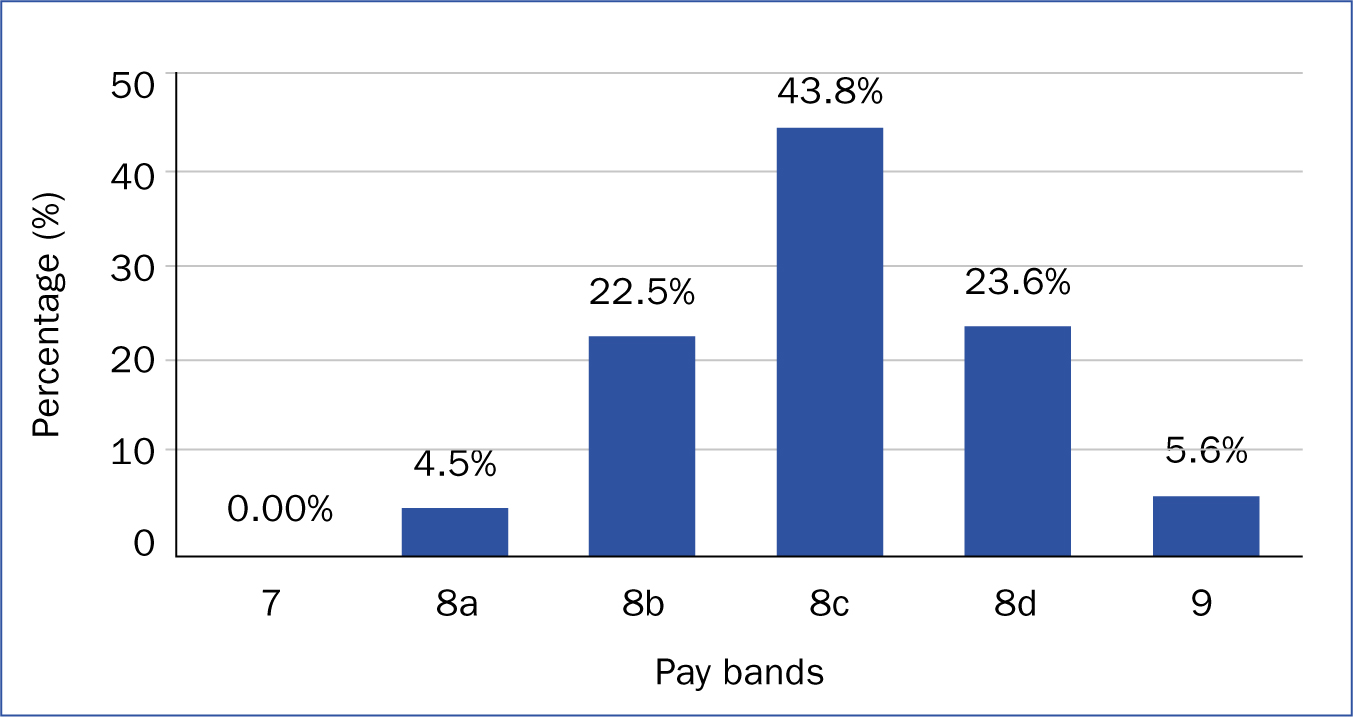

Figure 1 shows that most Heads of Midwifery and Directors of Midwifery reported that they were remunerated at the pay band 8c; however, the range from bands 8a–9 shows a significant variation across the country. This demonstrates a link between higher pay bands and Director of Midwifery roles, suggesting that the greater level of responsibility in relation to numbers of births and services the role oversees, the higher the level of remuneration.

There appeared to be a disparity between nurses and midwives at all levels concerning remuneration for senior nursing and midwifery roles. This was seen locally, regionally and nationally.

The highest level for a midwife to achieve at a national level is a band 9. This may explain Lord Hunt's comment (Hansard, 2017), when he described the challenge for midwives, who have to become directors of nursing to be represented at director level. This is especially difficult for midwives who are not dual-qualified, and creates a glass ceiling for members of the midwifery profession.

Midwives are encouraged to diversify and gain experience in other speciality areas, should they wish to apply for more senior roles and progress their careers. An important aspect of retention is to be clear about career opportunities and to be creative with development opportunities in the profession. It would benefit the profession if there could be greater availability of more senior, director-level roles for midwives.

Representation on the Trust Board

The findings of the survey demonstrated that just 4 respondents (4.5%) sat on their Trust Board. Other respondents reported that matters relating to midwifery were taken to the Trust Board via the following routes:

Membership of NHS Trust Boards is governed by the National Health Service Trusts (Membership and Procedure) regulations [1990] (Box 1).

The legislation directs that there is one allocated seat on the Trust Board that can be occupied by a nurse or a midwife; however, it is important that the board member fully represents the majority of the workforce and clinical areas. The Director of Nursing would be the person nominated by the chief executive officer (CEO). This would explain why only 4 respondents to the survey sat on their Trust Board. However, the survey responses highlighted the importance of inviting the Head of Midwifery and/or Director of Midwifery to attend the Board when maternity and midwifery issues are discussed so that they can represent the maternity agenda and respond accordingly to any queries.

It is important to note that more than 80% of respondents were seen as the professional lead for midwifery in their Trust. If this was not the case, the Director of Nursing or Chief Nurse was stated as the professional lead for midwifery.

Perception of the professional lead for midwives in England

To understand who the Heads of Midwifery and Directors of Midwifery saw as the professional lead for midwives in England, a free text question was asked.

Most respondents (n=42; 47.0%) identified the NHS England Head of Maternity, Children and Young People as the professional lead for Midwives in England; while 31 (35.0%) recognised the NHS England Chief Nursing and Midwifery Officer in that role. A small number (n=4; 4.0%) believed that it was the job of the RCM chief executive (Table 2). This therefore suggests that greater clarity is needed.

| Free Text | Responses n (%) |

|---|---|

| Not sure/Local maternity system/Local supervising authority midwifery officer | 2 (2.0) |

| Royal College of Midwives chief executive | 4 (4.0) |

| NHS England Chief Nursing and Midwifery Officer | 31 (35.0) |

| NHS England National Head of Maternity, Children and Young People | 42 (47.0) |

Development requested by Heads of Midwifery and Directors of Midwifery

A total of 74 responses were submitted to the question ‘What personal development would most assist you in your role currently?’ The responses were grouped into categories and listed in order of the number of times each category was mentioned (Table 3). Many areas for development were only mentioned once and appeared under the category of ‘other’.

| Category | Number of mentions |

|---|---|

| Leadership events, workshops and programmes | 16 |

| Coaching and mentoring | 12 |

| Trust Board exposure | 10 |

| Keeping abreast of national changes in maternity | 5 |

| Project management skills specific to Heads of Midwifery | 5 |

| Strategic planning | 5 |

| Finance and payment pathways | 4 |

| Resilience | 4 |

| Other | 13 |

The profile of midwifery and maternity in NHS Trusts

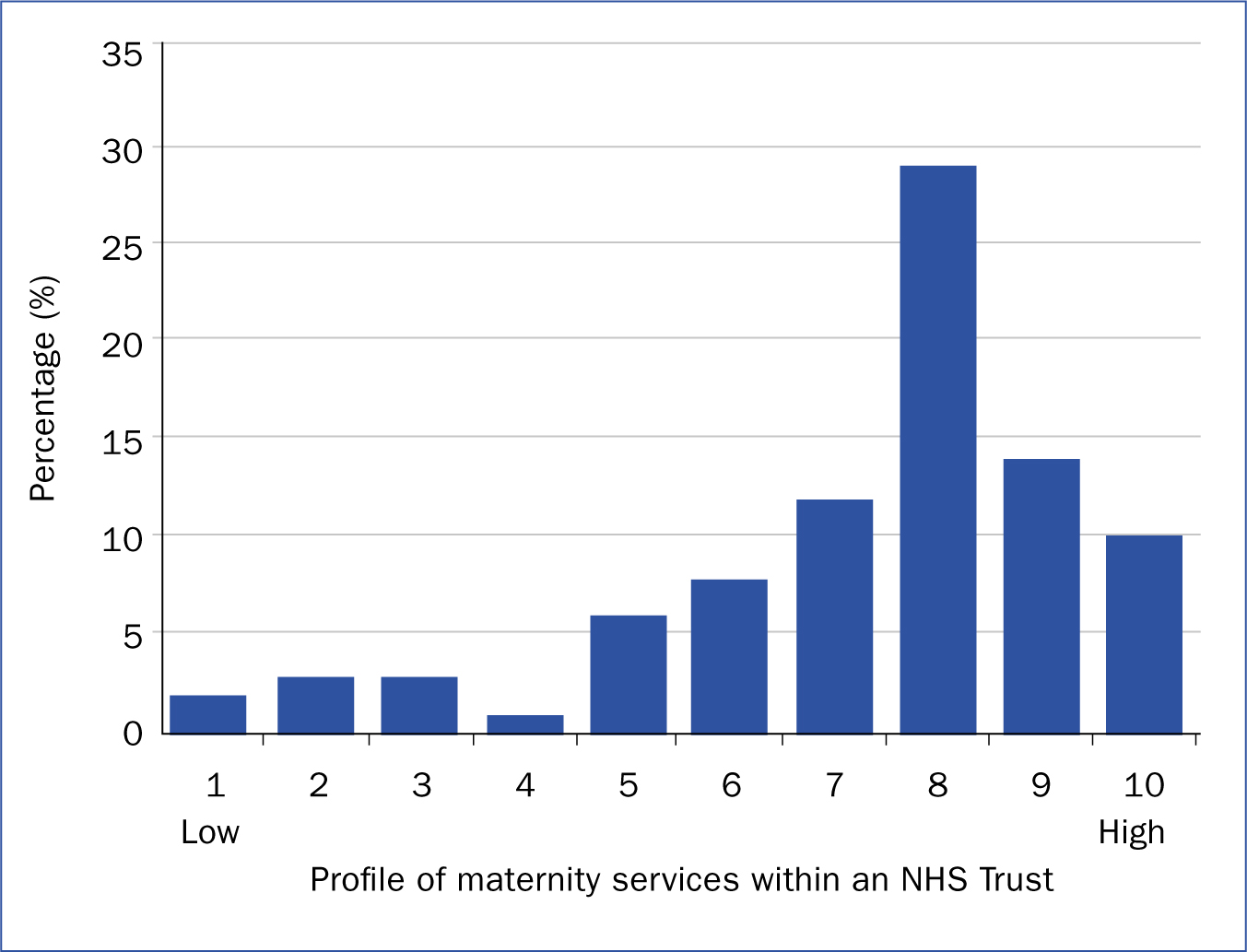

Respondents were asked to say on a scale of 1 (very low) to 10 (very high) where they saw the profile of midwifery and maternity in their Trust.

A larger number of respondents stated that maternity services had a high profile (Figure 2), which may reflect the focus on maternity transformation and implementation of Better Births. Respondents were asked to provide some characteristics of organisations with a high and low maternity profile in their Trusts. Responses are displayed in Table 4.

| Trusts where maternity and midwifery was high-profile | Trusts where maternity and midwifery was low-profile |

|---|---|

| ‘Well-resourced’ | ‘Maternity voice not heard and under-resourced’ |

| ‘Close and proactive Trust Board oversight of maternity and the maternity dashboard’ | ‘Micromanagement, which hinders innovation and development of maternity services’ |

| ‘Maternity agenda and midwifery voice heard at Board level’ | ‘Difficulty in getting maternity issues heard at Board level’ |

| ‘Trust Board receptive to business cases’ | ‘Financial constraints, having to prove value for money or defend staffing levels’ |

| ‘Chief executive well informed on maternity issues and raising the profile Trust-wide’ | ‘Lack of understanding and knowledge of maternity at Board level’ |

| ‘Involvement in key commissioning of services and quality initiatives that are seen to influence the nursing agenda (instead of vice versa)’ | ‘Staffing requirements not fully understood, and compared to nursing’ |

| ‘Supported but also under scrutiny’ | ‘Support is reactive rather than proactive’ |

| ‘Respected highly and valued by the executive team’ | ‘Required to regularly defend staffing numbers and uplift’ |

| ‘High profile has a positive impact on being able to provide a high quality, safe service’ | ‘No midwifery voice at an influential, executive level (responsibility without authority)’ |

| ‘Close and collaborative working between the Director of Midwifery, Head of Midwifery and Director of Nursing’ | ‘Inability to make changes, transform and innovate to improve quality and safety’ |

| ‘Strong maternity governance that serves as an exemple to others’ | ‘Difficulty getting business cases cited and agreed at Trust Board’ |

| ‘Director of Midwifery in-post’ | |

| ‘Director of Midwifery role clearly identified within the Trust clinical leadership strategy’ | |

| ‘Nominated non-executive director at Board level working closely with Director of Midwifery’ |

These characteristics are familiar from several Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspection reports of services where a ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’ rating has been given under the well-led domain (one of the five domains inspected by the CQC).

This demonstrates the importance of raising the profile of midwifery and maternity services within hospital Trusts to ensure that the service is adequately resourced and safe care is delivered.

Individual meetings

A total of 17 one-to-one meetings with senior NHS professionals, RCM and RCN chief executives and politicians were undertaken to gain a range of views regarding the profile of midwifery leadership in England. The meetings were focused on the standing of the midwifery profession in England and whether change was needed to address the midwifery leadership gaps; reflect the maternity transformation agenda; and understand and address the scale of the challenges to recruiting, training and retaining midwives.

Professional standing

According to the the Lancet Series on Midwifery:

‘The Midwifery profession is highly respected and greatly valued and is a vital solution to the challenges of providing high-quality maternal and newborn care for all women and newborn infants, in all countries.’

The NMC and the RCM have acknowledged anecdotally that a large proportion of the midwifery workforce does not hold a nursing qualification. A shortened midwifery training programme of 18 months is offered to postgraduate nurses; however, in some parts of the country, the number of nurses applying to undertake the shortened course is declining and the longevity of the course is being questioned.

It is important to acknowledge the changes taking place within the population of midwives in England, in order to give midwives visible leadership and a strong voice that is heard and responded to in the right place and at the right time. In the author's experience, the new generation of midwives do not tune in to ‘nursing language’ and will not hear messages directed to ‘nurses and midwives’. It is important that these significant changes are recognised and answered.

The State of Maternity Services Report 2018 (RCM, 2018) highlighted the fact that, for every 30 midwives trained in the UK, the workforce increases by the equivalent of one full-time midwife. Focused attention is required nationally to address this to ensure that the aims and ambitions of Better Births (National Maternity Review, 2016) and the Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019) are delivered.

Midwife numbers make up 6.6% (n=43 168) of the total number of registrants on the NMC register (n=690 773) (NMC, 2019). This demonstrates how easy it is for the midwifery profession to become ‘subsumed under nursing leadership’, a point made by Lord Hunt (Hansard, 2017). During the one-to-one meetings, some referred to midwifery as a ‘lost profession’, with midwives not being invited to meetings where a midwifery voice was required to demonstrate due regard. It also became apparent that midwives faced difficulties gaining promotion or were disqualified from shortlisting for not having a nursing qualification. Discussions during the one-to-one meetings included the need to discern whether the specific clinical qualification (nursing or midwifery) was relevant in senior director roles.

Addressing the gap

Other interviewees articulated the need for leaders of the profession to ‘manage up’ in order to negotiate a Director of Midwifery role at Trust level with direct access to the Board on all maternity matters. It was certainly apparent from the one-to-one meetings that the relationship between the Director of Nursing and the Director of Midwifery at Trust level was crucial, with some stating that they should be professional equals. During the meetings, chief executives from both the RCN and the RCM agreed that England should have a Chief Midwife to demonstrate the significant difference in the professions and apply due regard at a national level. This could then be replicated at regionally in England by having a director-level role, working alongside other Directors of Nursing and Directors of Quality, focusing on all aspects of maternity services and midwifery, including maternity transformation, quality and safety, and improvement programmes. The role could also encompass other portfolios as required.

It was acknowledged during the one-to-one meetings that provider organisations could do more to develop their senior midwives and identify a talent pool of aspiring directors. Responses highlighted the following:

Titles

Each person interviewed during the one-to-one meetings recognised that the title and level of authority held by the most senior midwife in England needed to be reviewed. The title of ‘Chief Midwife’ is already used by executive NHS Leaders to describe this role and it remains unclear as to what the barriers are to instigate this change, but as NHS England and NHS Improvement work towards an integrated model, and a review of staffing structures is anticipated at a national and regional level, this may be the right opportunity.

A Chief Midwife in England would greatly increase the professional capital for midwifery, ensuring that the profession and its challenges were represented before the Department of Health, NHS England, NHS Improvement and other bodies. Prioritising the wellbeing of mothers and babies at the highest level, and maximising the contribution of midwives, is important as the NHS leads on integrated care while improving population health and reducing health inequalities as outlined in the Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019).

The equivalent roles in Scotland are Chief Midwifery Advisor and Associate Chief Nursing Officer, who each have similar responsibilities for briefing Government ministers and influencing policy as the current role in England. A key advantage in Scotland is that the role is well known to all midwives which is not the case in England, as Table 2 demonstrates.

The ICM supports the participation of midwives at the highest level of policy and decision-making at global, regional and local levels. In 2017, following a programme of work led by the ICM, Kyrgyzstan appointed a Chief Midwife in the ministry of health to ensure a strong presence and a voice for the midwifery profession as well as actively participating in policy discussions. Before the establishment of this post, all midwifery activities were overseen by the country's Chief Nurse.

During a one-to-one conversation, the President of the ICM stated that few countries have a Chief Midwife, which is of great concern to the ICM. The president also cited worries that midwifery is becoming isolated, despite the ICM's belief in opportunities for midwifery globally, such as the integration of midwifery in the public health agenda. In the President's view, given the UK's global influence, the appointment of a Chief Midwife in England would demonstrate the value and importance of the profession and would have an international effect.

For further discussion

A Director of Midwifery role should be considered in every maternity service. They should work closely with the Director of Nursing and have direct access to the Trust Board on all issues relating to maternity and midwifery, alongside a non-executive director as the Board maternity safety champion.

Within NHS England, a Director of Midwifery role should be considered, with responsibilities as required by individual regions.

Consideration should be given to the appointment of a Chief Midwife in England with professional responsibility for midwives and midwifery, and working alongside the Chief Nursing Officer. The remit would include setting strategy in line with the Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019), briefing the Department of Health and government ministers on midwifery and maternity matters, and representing England to the ICM and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Conclusion

Midwives need a means by which they can work in partnership and collaboration with nurses and not be subsumed beneath the nursing agenda. A Chief Midwife in England and senior midwifery leadership at regional and local levels would give a voice to midwives across the country, maximising the benefits of midwifery care for women and their families. It has been recognised by UNFPA, ICM and WHO that midwives prevent approximately two-thirds of deaths among women and newborns globally (Renfrew et al, 2014), and the return on investments in midwives are seen as the best buy in primary healthcare. As the RCM's former Director for Midwifery, Louise Silverton, wrote:

‘The Lancet series on Midwifery […] shows that investment in midwives, their work environment, education, regulation and management can and does improve the quality of reproductive, maternal and newborn health in all countries.’

Policy drivers such as Better Births (National Maternity Review, 2016) and the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019) provide the opportunity for wide-ranging organisational changes that could provide great benefits and improve outcomes for women and their families. Significant leadership capabilities, formal authority and confidence are required to do things differently. New leadership structures can and should be considered to enable the very best midwifery and maternity care to be delivered and sustained; ‘remaining the same’ should not be an option.

‘You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete’ (Richard Buckminster Fuller).