Where are you from? At first glance, this question seems innocuous, emanating from the curiosity of a patient or colleague. However, when the answer to this question is followed by ‘where are you really from?’ or a variation on that query, it can act as a rejection of a person's sense of self-identity. Regardless of intent, this is a microaggression, specifically a racial one. The term ‘racial microaggression’ was first coined by Chester Pierce in 1970 and reintroduced by Derald Sue Wing in 2007 (Sue et al, 2007). Racial microaggressions can be thought of as frequent, subtle and often unintentional insults towards a marginalised racial group (Williams et al, 2021). The impact of racial microaggressions cannot be overstated and the cumulative effects have been shown to lead to poorer physical and mental health outcomes for those on the receiving end (Wong et al, 2014; Spanierman et al, 2021). This article explores the types of racial microaggressions that may be encountered in the workplace, considers how these could be addressed and empowers people to become allies or active bystanders.

What are racial microaggressions?

Racial microaggressions, by their nature, are subtle slights or insults based on a person's race, that may go unnoticed by their perpetrator or those other than the recipient (Smith and Griffiths, 2022). Although the perpetrators of racial microaggressions tend to be from non-marginalised racial groups, they can also come from marginalised racial groups. This reflects the fact that even among marginalised racial groups, there is a great deal of heterogeneity. This is despite the common tendency to use classifications such as Black, Asian and minority ethnic to describe a population with significant differences as a homogenous entity. Sue et al (2007) classified racial microaggressions into three main categories: microinsults, microassaults and microinvalidations.

Microinsults

Microinsults are verbal or non-verbal acts of rudeness or demeaning behaviour on the basis of race (Sue et al, 2007; Kim et al, 2019). Examples include being dismissive of colleagues of a marginalised racial group, not paying attention or appearing distracted in conversations with colleagues from marginalised racial groups, or implying that a person's career progress or appointment is a result of their race (Box 1).

Box 1.Examples of microinsults

- ‘Are you the new cleaner?’

- ‘Oh, so you got the job? I guess they had a quota to fill.’

- ‘I love your hair, it's so exotic. Can I touch it?’

- ‘Where are you really from?’

- Assuming someone's ethnicity based on their skin colour

- ‘When is the real doctor getting here?’

- ‘Your English is surprisingly good.’

- ‘I expected you to have a different accent.’

- ‘Are you sure you know what you're doing? Should we wait for [junior White colleague] to get here?’

- ‘I wish all foreigners were more like you.’

Microassaults

These are the most overt microaggressions and can include the use of racial slurs or overt hostility towards colleagues from a marginalised racial group (Kim et al, 2021). Examples include the direct use of a racial slur towards a person from a marginalised racial group or the use of race-based stereotypes (Box 2).

Box 2.Examples of microassaults

- ‘What's up my [n-word]?’

- ‘There's too many Asians in this town, I wish it was like it used to be.’

- ‘The kitchen has a funny smell, must be those new Indian doctors with their food.’

- ‘Oh you're [insert ethnic group]? So did your parents force you to do medicine?’

- ‘If you don't like it here why don't you go back home?’

- ‘I wouldn't leave your phone out, [Black person] will probably steal it.’

- ‘Your names are always so hard to pronounce, I'm just going to call you John.’

Microinvalidations

Microinvalidations are acts that demean a person's racial identity or lived experience (Kim et al, 2019). This can take the form of constantly confusing the only two people from a marginalised racial group with each other despite clear differences in appearance or constantly mispronouncing a person's name despite being corrected each time (Box 3).

Box 3.Examples of microinvalidations

- ‘I don't see race, I treat everyone the same.’

- ‘Racism doesn't exist in this day and age, just look at you, you're doing well for yourself.’

- ‘You'll never be English, but British, sure.’

- ‘It's so hard to get any opportunities as a White person these days because of all these quotas.’

- ‘Stop being so sensitive, you're reading too much into it. I'm sure they didn't mean it in that way.’

- ‘If you work hard, anyone can succeed.’

- ‘Race is less of a factor than you think.’

- ‘I'm not racist, my partner/friend/relative is a person of colour.’

The impacts of racial microaggressions

As racial microaggressions are subtle, it would be easy to assume that they have little or no impact. However, studies have shown significant impacts to both the physical and mental health of recipients as a result of their cumulative effect (Paradies et al, 2015; Ohrnberger et al, 2017; Sudol et al, 2021). It is important to note that the cumulative impacts can apply to both doctor and patient. In the UK, several examples of the cumulative effects of microaggressions can be seen in both groups.

Professional consequences

Several reports have documented the difficulties faced by doctors from marginalised racial groups. The medical workforce race equality standards report highlights poorer outcomes in doctors of marginalised racial groups compared to their White counterparts (NHS England, 2021).

The report highlights that doctors from marginalised racial groups:

- Have proportionally fewer clinicians at clinical or medical director level

- Have proportionally fewer clinicians in consultant roles

- Have greater numbers being subject to complaints, referrals and investigations

- Are more likely to have an adverse annual review of competence progression outcome

- Are less likely to pass postgraduate examinations

- Are more likely to have suffered abuse, bullying or harassment at work.

These findings are supported by the General Medical Council's (2023) report into tackling disadvantage in medical education, which also highlighted the lower rate of offers into specialty training made to people from marginalised racial groups compared to their White counterparts.

The data are conclusive and show a clear disparity in outcomes between doctors from marginalised racial groups and their White peers. While the reasons for these outcomes are likely to be multifactorial, it would be remiss to not consider racial microaggressions as playing a significant role. Encouragingly, there is an acceptance of the data and several action plans have been put in place to try and address the negative outcomes (NHS England, 2023a, b).

Patient consequences

The existence of health inequalities in the NHS is widely recognised. A rapid review by the NHS Race and Health Observatory highlighted inequalities in access to both adult and child mental health services, access to and outcomes of maternity services and potentially in access to genetic testing among others (Kapadia et al, 2022). The Marmot review and its 10-year update also highlighted health inequalities for patients in marginalised racial groups, such as a lower disability-free life expectancy than their White counterparts (Marmot et al, 2020).

Disparities became more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients from marginalised racial groups had higher rates of infection, hospitalisation and death than their White counterparts (Lo et al, 2021; Osama et al, 2021). The disparities in general health outcomes in marginalised racial groups compared to White patients may also explain differences in vaccine uptake. A large study reviewing vaccine hesitancy and uptake found that people from marginalised racial groups were more hesitant and therefore less likely to have received a COVID-19 vaccine than their White counterparts (Nguyen et al, 2022).

Consequences for physical health

As explored earlier, racial microaggressions have a cumulative effect that can impact on physical health. The effect of racism on physical health is well documented, with studies indicating a link with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, poor sleep and physical fatigue (Paradies et al, 2015). A proposed explanation is that frequent stressors cause a constant physiological stress response leading to elevated heart rate, blood pressure and cortisol levels (Pascoe and Richman, 2009).

In addition to direct impacts on physical health, racial microaggressions can also lead to increased unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking or alcohol use, and decreased levels of physical activity (Pascoe and Richman, 2009). These negative health behaviours compound the issue and demonstrate the devastating impact that microaggressions can have.

Consequences for mental health

Racial microaggressions also have a negative impact on mental health. Depression and anxiety are among the most common mental health issues reported by victims of racial microaggressions but are not the sole complications (Paradies et al, 2015). Among the physician population, racial microaggressions have been shown to increase the rates of burnout (Sudol et al, 2021).

Other mental health impacts include increased suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem and paranoia (Paradies et al, 2015). A systematic review by Pascoe and Richman (2009) reported an increased probability of developing mental illness as a result of the cumulative effects of racial microaggressions and similar experiences. Given the interplay between physical and mental health (Ohrnberger et al, 2017), the effects of racial microaggression on mental health are likely to impact on physical health and vice versa.

Intersectionality

While racial microaggressions form the basis of this article, a person's identity is rarely defined by one characteristic. This forms the basis of intersectionality, whereby a person cannot be distilled into one aspect of their being but rather the interplay of all of their characteristics (Crenshaw, 2013). It is important to note that microaggressions can occur as a result of gender, sexuality, disability, religion or on the grounds of any other protected characteristic (Sue, 2010). Table 1 gives examples of microaggressions related to some other protected characteristics.

Table 1. Examples of wider microaggressions

| Gender | Female doctors repeatedly being confused for nurses, despite wearing a different uniform and a name badge clearly stating their role. |

| ‘You should become a GP since you're a woman, it will be easier for you to have a family that way.’ | |

| Patients or other staff assuming a male doctor is more senior than a female doctor. | |

| ‘You should smile more, you'd look so much friendlier/prettier.’ | |

| Consistently asking the female juniors to go on the coffee round. | |

| Patients asking female doctors to get them a cup of tea during ward round. | |

| Focusing on more ‘soft’ skills when describing a female doctor's strengths. | |

| Consistently asking female staff to complete more labour-intensive or admin-focused tasks. | |

| Female doctors being described as ‘bossy’ when men are ‘confident,’ or being described as ‘lacking assertiveness’ when men are described as ‘team workers.’ | |

| Being asked about reproductive plans in a work setting and/or people giving unprompted reproductive advice. | |

| Sexuality | ‘I couldn't even tell you were gay/lesbian.’ |

| ‘You can't be [insert specialty] if you're gay.’ | |

| ‘You're not a lesbian, you've just not met the right man.’ | |

| ‘I usually don't let men examine me but you're gay so it's fine.’ | |

| ‘Bisexuals are just confused, pick a side.’ | |

| ‘I thought you were gay because of the way you talk. Are you sure you're not?’ | |

| Disability | ‘You can't be disabled, there's nothing wrong with you.’ |

| ‘Don't ask them, they won't be able to do it.’ | |

| ‘Are you sure you can do this, I think it may be too difficult for someone like you.’ | |

| ‘Why don't you just do the paperwork, it's all you're good for.’ | |

| ‘How can you be a doctor? You're disabled!’ | |

| ‘You're better off doing something else, medicine is hard work.’ |

How to address microaggressions

Having explored the myriad of ways racial microaggressions can impact the physical and mental health of doctors and patients, this article now explores what can be done to address them. It is important to note that there are a variety of interventions and actions to help address racial microaggressions and there is no single solution. The solutions presented here will not suit every situation or individual.

Education

As with many issues, education is key to finding solutions to problems. The subtlety of racial microaggressions means they often go unnoticed, and their existence may even be questioned. Pearce (2019) suggested that using the testimony of victims of microaggressions to show their impact may be helpful in educating the unaware. It can also help to start a conversation about race, something that is often avoided as it can cause uncomfortable feelings for people from marginalised and non-marginalised racial groups alike (Song, 2020; Obasi, 2022). Additionally, by introducing case vignettes into education sessions and exploring their meaning and impacts, participants can consider how they may respond either as a victim or a witness (Pearce, 2019).

Actions

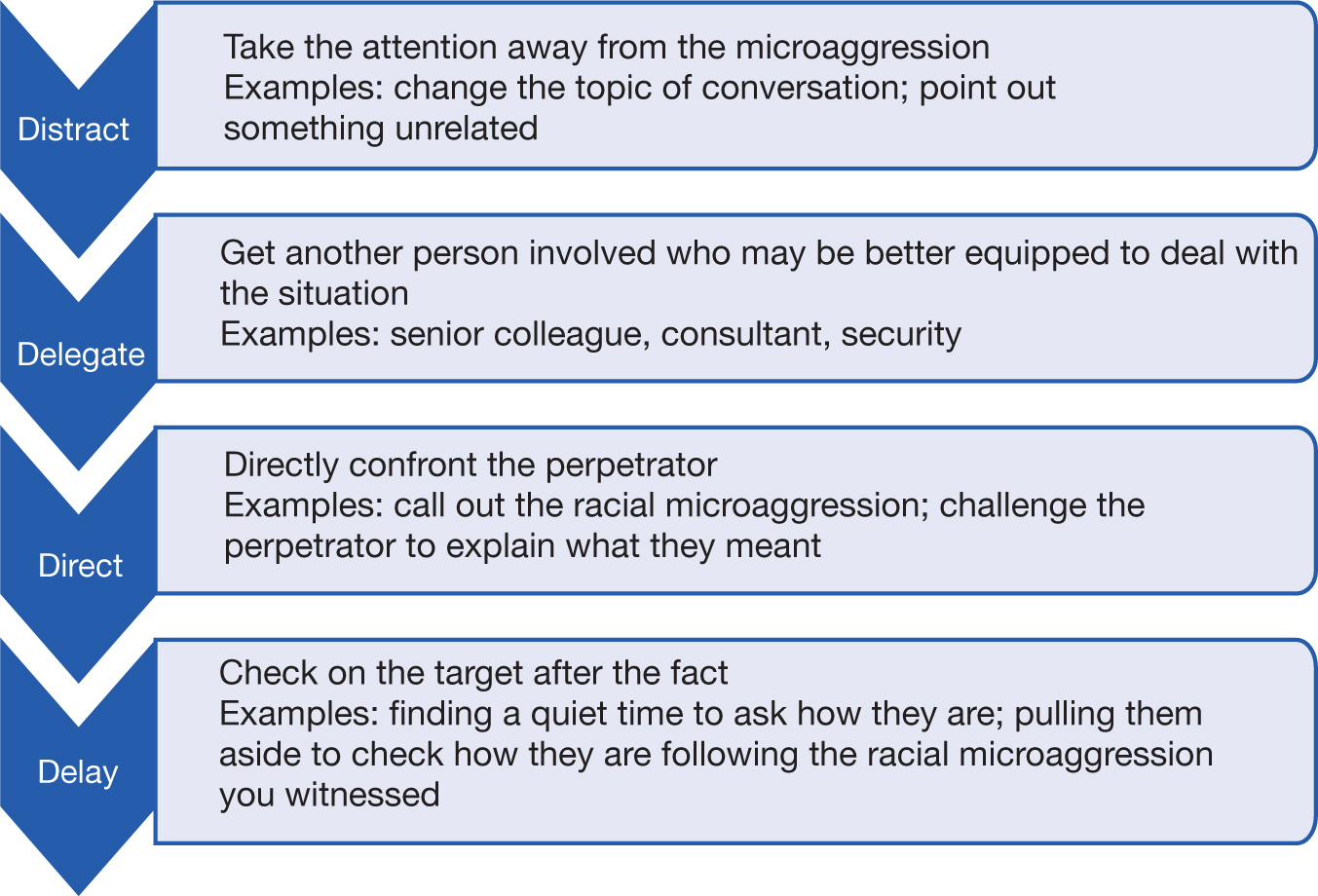

There is no one solution to tackle racial microaggressions. The most important consideration when deciding what action to take is one's physical and psychological safety in doing so. It can also be helpful to think of actions in terms of the role or proximity to the racial microaggression. Sue et al (2019) propose the consideration of actions through three lenses – targets, allies and bystanders. This article also proposes two models for addressing racial microaggressions: the 4Ds, whereby distraction, delegation, direct action or delay can be used, dependent on the situation (Figure 1) and PACE, which acts to turn an unconscious comment or action into a conscious one by probing the meaning behind a comment or action, alerting a perpetrator to possible interpretation, challenging them if there is non-acceptance and ending interaction if it is clear that there is an unwillingness to acknowledge the impact of the racial microaggression (Figure 2).

Targets

Targets, as the name suggests, are the recipients of racial microaggressions. They are people from marginalised racial groups and are often looked upon to provide the solutions while dealing with the effects of the racial microaggression (Sue et al, 2019). One potential strategy is confrontation, as described by Houshmand et al (2019). Examples may include calling out stereotypes or insults, confronting non-verbal acts and explaining the impact that this has had on them, in the hopes it will educate the perpetrator about the harms of their actions, unconscious or otherwise. However, not all targets are willing to confront what they identify as racial microaggressions. Ignoring racial microaggressions or choosing not to engage is another strategy that has been adopted. Examples include leaving employment as a result of racial microaggressions and choosing not to shop in places where non-verbal racial microaggressions occur (Houshmand et al, 2019). The decision to ignore or avoid racial microaggressions may be the result of racial battle fatigue, a phenomena born from a weariness of the relentless nature of racial microaggressions and the seeming lack of change in their frequency (Gatwiri, 2021). While the act of ignoring or avoiding racial microaggressions may have benefits to physical and mental wellbeing, it can also result in the loss of opportunities, the cost of which must be weighed against the potential harm from remaining in environments with frequent microaggressions.

Allies

Allies are those who are from non-marginalised racial groups who actively support people from marginalised racial groups in the hopes of ending the disparities between the two groups (Sue et al, 2019). The importance of allyship cannot be overstated, as allies from non-marginalised racial groups are more likely to occupy positions of power and more likely to have their voices heard when calling out racial microaggressions. As such, allies can address microaggressions in several ways. As an ally, important steps include calling out microaggressions in the absence of people from marginalised racial groups, educating others from non-marginalised racial groups on the impacts of racial microaggressions, advocating for greater representation of marginalised racial groups in positions of power and creating an environment where people from marginalised racial groups feel able to share their experience (Selvanathan et al, 2023). Importantly, allies must also recognise and reconcile with their own privilege and know when to take a step back to enable marginalised racial groups to tell their own stories in their own voices (Droogendyk et al, 2016).

Bystanders

While there can be overlap between bystanders and allies, bystanders are less likely to be actively involved in advocating for people from marginalised racial groups and are more likely to stumble across situations in which racial microaggressions occur (Sue et al, 2019). When faced with these situations, bystanders may fail to recognise racial microaggressions or avoid any involvement through fear of receiving similar treatment to the targets (Sue et al, 2019). Bystanders who identify that a racial microaggression has taken place may choose, much like targets, to be active or passive (Figure 1). An active bystander could act to dispel racial stereotypes or to acknowledge the experience of a person from a marginalised racial group that may have been dismissed by a perpetrator (Sue et al, 2019). A passive bystander may seek to check in on a target after the event to ensure they know that their experience of a racial microaggression was noted and to offer them support (Dada and Laughey, 2023). Not all bystander actions can be deemed helpful, for example trying to rationalise a racial microaggression, dismissing the target as being overly sensitive or reading too much into things, or refusing to believe that a comment or action was racist regardless of the perpetrator's intent (Sue et al, 2019). This could transform a bystander into a perpetrator of a racial microaggression.

Resistance

While the onus should never be on the target of racial microaggressions to deal with their impacts, building resistance to them has become a necessity to mitigate the physical and mental health effects. Resistance may be built in the form of seeking community and collective support in others from marginalised racial groups. The ability to share experiences in a psychologically safe space without the need to justify or qualify the racial microaggressions can be empowering (Spanierman et al, 2021). Another strategy for resistance is in the rejection of the stereotypes associated with marginalised racial groups and a refusal to conform with what is often a White male centric ‘norm’ (Spanierman et al, 2021). Being able to bring one's authentic self into an environment means people are more likely to feel fulfilled and seen for who they are rather than who they are expected to be (Brown and Del Rosso, 2022). Self-care is another mechanism that has been shown to be helpful. Activities that promote positivity in one's identity, whether through community activities or positive stories of other people from marginalised racial groups, can also prove beneficial (Houshmand et al, 2019; Spanierman et al, 2021).

The challenges of culture change

The actions suggested in this article can be attempted on an individual basis, but changes to the wider workplace culture are likely to be more effective. However, as with most change, there are likely to be barriers, perceived or otherwise. First, denial of the problem. As explored previously, racial microaggressions are commonly subtle and so may go unnoticed or be dismissed as oversensitivity. This can be disheartening to those trying to shine a light on the problem in order to shift culture. Second, the diversity in the leadership of organisations may not reflect those likely to experience racial microaggressions. Anyone can be an ally, but those with lived experience are more likely to be invested in driving cultural change from the top down. Last, for the more direct actions, there may be an unease at highlighting racial microaggressions, and in challenging or indeed trying to educate perpetrators. This may be a manifestation of racial battle fatigue given the toll that racial microaggressions can take on its targets and recipients. While not an exhaustive list, these challenges, among many others, should be considered when starting to create a more inclusive workplace culture.

Conclusions

Racial microaggressions can have a devastating impact on the physical and mental health of their victims. Owing to their subtle nature, racial microaggressions often go unnoticed by those not from marginalised racial groups and can therefore present complexity in the response when they are raised. The most important way to address racial microaggressions is by being able to identify them. People from marginalised racial groups are likely to face some form of racial microaggression daily, so the onus is on those from non-marginalised racial groups to educate themselves as to the words and actions that can constitute racial microaggressions and acknowledge the impact they can have. The authors hope that by highlighting this issue, they can inspire a generation of allies and active bystanders that will lead to a growing understanding of and eventual eradication of racial microaggressions.

Key points

- Racial microaggressions are subtle slights or insults that can have a devastating impact on the physical and mental health of their recipients.

- While racial microaggressions are usually perpetrated by people from non-marginalised racial groups, people from the same or other marginalised racial groups can also be perpetrators.

- There is no single solution when it comes to addressing racial microaggressions, but use of the 4Ds (distract, delegate, direct, delay) or the PACE (probe, alert, challenge, ending) frameworks may help.

- Allyship is a powerful tool in the fight against racial microaggressions but cannot be effective without acknowledging and reconciling with one's privilege.