Maternal sepsis is now the leading cause of direct maternal death in the UK (Knight et al, 2015), as well as being a major cause of maternal death and morbidity worldwide (Bamfo, 2013). Arulkumaran and Singer (2013) report that there are more than five million new certified cases of maternal sepsis each year worldwide, with an estimated 62 000 deaths. Historically, it was one of the most prevalent causes of maternal death—known as puerperal fever or childbed fever—and was responsible for more than 50% of maternal deaths in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries (Ronsmans et al, 2006).

In the UK, the maternal sepsis death rate has increased from 0.85 deaths per 100 000 in the years 2003–05 to 1.56 per 100 000 in the years 2009–13 (Knight et al, 2015). For this reason, a collaboration was established between the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (Dellinger et al, 2013) to address the number of deaths through sepsis in the maternity population. Both organisations outline the need for education and the promotion of teaching an escalation approach as well as triggers and guidelines for intervention. The RCOG divides maternal sepsis into three categories: sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock (Table 1).

| Sepsis category | Clinical signs |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | Infection, or manifestations of infection, in pregnant women or women up to 6 weeks postnatal |

| Severe sepsis | Sepsis compounded by organ dysfunction or tissue hypoperfusion |

| Septic shock | Hypoperfusion regardless of adequate intravenous fluid therapy |

The need for good-quality training on the subject of maternal sepsis is indisputable, and it was for this reason that a maternal sepsis training package was initiated by the researcher, based on the maternal sepsis guideline at the Trust involved. The maternal sepsis guideline was based on the RCOG (2012a; 2012b) Green-top Guidelines and considered by the Trust to be a comprehensive document.

This study aimed to assess the impact of this intervention, to substantiate its validity and ensure continuing support by the Trust.

Maternal sepsis training package

Two elements made up the sepsis training package available to staff during April 2013 – September 2013:

In the UK, the maternal sepsis death rate increased from 0.85 deaths per 100 000 in the years 2003–05 to 1.56 per 100 000 in the years 2009–13

The training, based on the guidelines, was heavily influenced by the Modified Early Obstetric Warning Score (MEOWS). Developed as a physical early warning system that utilised patient observations in order to prioritise care, the MEOWS chart is a maternity-specific tool that is now integral to the provision and escalation of care in maternity units in the UK (Singh et al, 2012). Table 2 lists the specific observation categories and indications of a ‘red’ or ‘yellow’ score.

| Observation | Red score | Yellow score |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | < 35.1° or >37.9° | 35–36° or 37.5–37.9° |

| Pulse | > 100° | 35–50° or 100–110° |

| Respiration | < 10° or > 30° | 20–30° |

| Systolic blood pressure | < 80° or > 150° | 80–90° or 140–150° |

| Diastolic blood pressure | < 40° or > 100° | 40–50° or 90–100° |

| Lochia/wound | n/a | Abnormal |

| Pain score number (0–5) | n/a | 4–5° |

| Looks unwell | n/a | Yes |

MEOWS Modified Early Obstetric Warning Score

All grades of midwives and obstetric doctors had access to and completed either or both elements of the training. Over the 6-month period, approximately 150 midwives and 30 doctors accessed the training.

Methodology

This study was undertaken as an audit, which is a process used to critically appraise the quality of clinical care in a systematic fashion. This can include the procedures and processes of a diagnosis, the treatment and care provided or, as in this case, the impact of a training initiative (Paton et al, 2015). Audit is a valuable tool to assess the quality of service delivered as well as presenting an opportunity to re-evaluate the intervention's necessity and consider a different pathway (Begley et al, 2015).

Audit was chosen as a methodology for this study as the aims and objectives follow the definition by Begley et al (2015). The maternal sepsis training package has large financial implications when considering provision of the course to large numbers of staff. The cost of the course, as well as the number of staff released from clinical practice, must be considered if there is shown to be little value of training on quality impact. In the current financial situation, health care organisations still need to deliver high-quality training that is well evaluated by staff; however, if there is little impact on care, initiatives must justify their value for money (Drummond et al, 2015).

Aim

This audit aimed to examine whether there was a statistically significant impact of the maternal sepsis training package, provided during the period 1 April – 30 September 2013 (quarters 2–3), on maternity staff's documented compliance with the Trust's maternal sepsis guideline within maternity notes.

Objectives

Study design

Population

The population for this audit was maternity service users who were pregnant or < 6 weeks postnatal, and receiving care from the Trust involved in the study between 1 January – 31 December 2013.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

There was no control group with any of the women showing signs or symptoms of sepsis, regardless of manage ment, owing to the unethical nature of knowingly omitting care. There was no randomisation as all women showing signs of sepsis were included in this study.

Women who were treated prophylactically for sepsis, but showed no physical signs of sepsis or any MEOWS observations indicating sepsis, were excluded.

Interventions

The maternity notes for each woman highlighted through the data collection process, who also fit the inclusion criteria, were reviewed against a pro forma. The pro forma was designed to apply the 12 comparable variables of the Trust maternal sepsis guideline. Each variable was assessed as compliant or not compliant against the documentation in the maternity notes. If the variable was achieved in the notes it received 1 point.

Comparators

The 12 variables were:

Outcomes

The 12 variables were combined into a final score for each woman per quarter. The total of all women's scores was combined for a mean quarterly total, from which quarter 1 could be reviewed against quarter 4 in order to assess whether there was a statistically significant increase owing to the implementation of the training package in quarters 2–3.

Method

Data collection

Sample population data were gathered from three sources:

The Trust involved in the study had an electronic data information system specifically designed for the maternity unit. At points throughout a woman's pregnancy, staff enter data onto the system, which is used for care and communication as well as audit and research. A list of those women who had been entered onto the system, who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, was requested. Relying on one data source can result in a questionable study validity (Friedman et al, 2015), so an additional two sources were requested.

The second source of data was the Trust's coding department, which specialised in producing data on all patients and service users, in this case, having had an infection episode. Coding departments are common in UK Trusts and are often situated on site. All health care records and notes are returned to relevant coding departments after a patient or service user is discharged, so that the episode can be coded against a national framework. These codes are the information on which Trusts receive government payments for the care they deliver. As maternity notes are handheld, they are not returned to coding until after discharge from maternity services. For this reason, all episodes of maternity care are coded through the maternity information system mentioned above (Cimino, 1996).

The researcher reviewed all Trust coding headings relevant to the inclusion criteria, from which a list was compiled to be cross-referenced against hospital numbers. The coding headings highlighted by the researcher were:

As relevant coding headings did not exist to reflect the antenatal population, to ensure these women were also represented in the data any maternity patient admitted to ITU or HDU was used, as this would highlight any antenatal women with sepsis who did not eventually end up with one of the previous codes. As there were relatively small numbers of women admitted each year to the ITU or HDU, it was possible for the researcher to include or exclude them in a timely fashion.

The third source of data was the information sent to UKOSS by the Trust. UKOSS is an initiative that combines the resources and data of the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. It collects, collates and researches data concerning rare conditions and high-risk pregnancies. Trusts are encouraged to report on serious pregnancy outcomes that are usually highlighted through the patient safety reporting system, including sepsis. This information was held by the patient safety midwife within the maternity unit.

As the data were collected separately from the three sources, it was expected that there would be some duplications. When all sample data had been collected, the researcher removed duplications before data analysis.

All 12 months' worth of data collected were retrospective in nature and recorded at quarterly intervals. The researcher was the main person collecting the data; however, assistance was provided from an experienced band 6 midwife.

Data analysis

Owing to the quantifiable design of the pro forma used for data collection, the data could be quantified into the numerical measurement of ratio data, with a higher degree of considered precision than ordinal or nominal data. Data collection was designed in this way in order for statistical analysis to be possible, to enable a broader scope for this study (Moule and Hek, 2011). The main distinguishing trait of ratio data is that there are intervals in the data that include an absolute zero, which represents a meaning. This influences the type of statistical tests that can be applied (Gray, 2013).

Each woman's score out of 12 variables on the pro forma was collected. For each quarter, all mean scores were collated to provide a mean score increase or decrease throughout the year. To evaluate any statistical significance, a t test was completed of the mean score between quarter 1 and quarter 4, which would show whether there was a statistically significant impact of the maternal sepsis training package on maternity staff's compliance with the Trust maternal sepsis guideline, as documented in maternity notes.

Data management

No identifiable information was retained. All electronic data were stored in a protected computerised project space, maintained by the Trust in accordance with the NHS data security policy. The space was password-protected with encryption methods. Paper-based information was stored in a locked project cupboard at the Trust. The researcher operated in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. Data will be retained for a period of at least 10 years from the date of publication.

Time frame

This work was conducted as a longitudinal study as data were collected over the 4-month period January–April 2014. This was done to increase the probability that all maternity notes would be available for examination without hindering care for inpatients.

Ethical considerations

This study has complied with ethical considerations and received a favourable ethics opinion from the University of Surrey, as well as the Trust R&D. National Research Ethics Service did not require an application for this audit. At the Trust involved in this study, all women's handheld notes include a consent form entitled ‘Information and consent for data collection, storage and access’. All women are required to sign the form if they consent to their anonymised records being used for audit purposes. This form remains in their handheld notes for the duration of their pregnancy and is retained after the pregnancy for the shelf-life of the notes, which at present is 25 years. The form informs women that, in regard to their care:

‘Some of the information may need to be shared with other staff and health care agencies to facilitate care required for you and your baby and may be used for statistical data analysis to help monitor quality and assist in allocating resources appropriately.’ (Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 2013: 2)

No notes were used that did not contain a signed consent form.

In the unlikely event that there was unsafe or dangerous care noted, the researcher would have escalated the situation to the patient safety team.

Issues of reliability and validity

In this study, the consistency of measurements are the 12 variables of care in the guideline. They are unchanging regardless of the woman or member of staff collecting the data, and are the fixed aspects of the pro forma.

Results

A total of 330 women were highlighted through all three data collection sources. After duplications were removed, 320 remained. Of those, 168 women were assessed as appropriate for the study as per the inclusion criteria.

The women eliminated from the study were excluded largely because they had been provided with prophylactic antibiotics for conditions such as group B streptococcus infection; however, owing to limited overall codes available to the coding department, these women had been coded into the headings chosen by the researcher. Ten women were eliminated as they had been coded incorrectly and two further women were eliminated from the study population as their pro forma was incomplete, owing to researcher error.

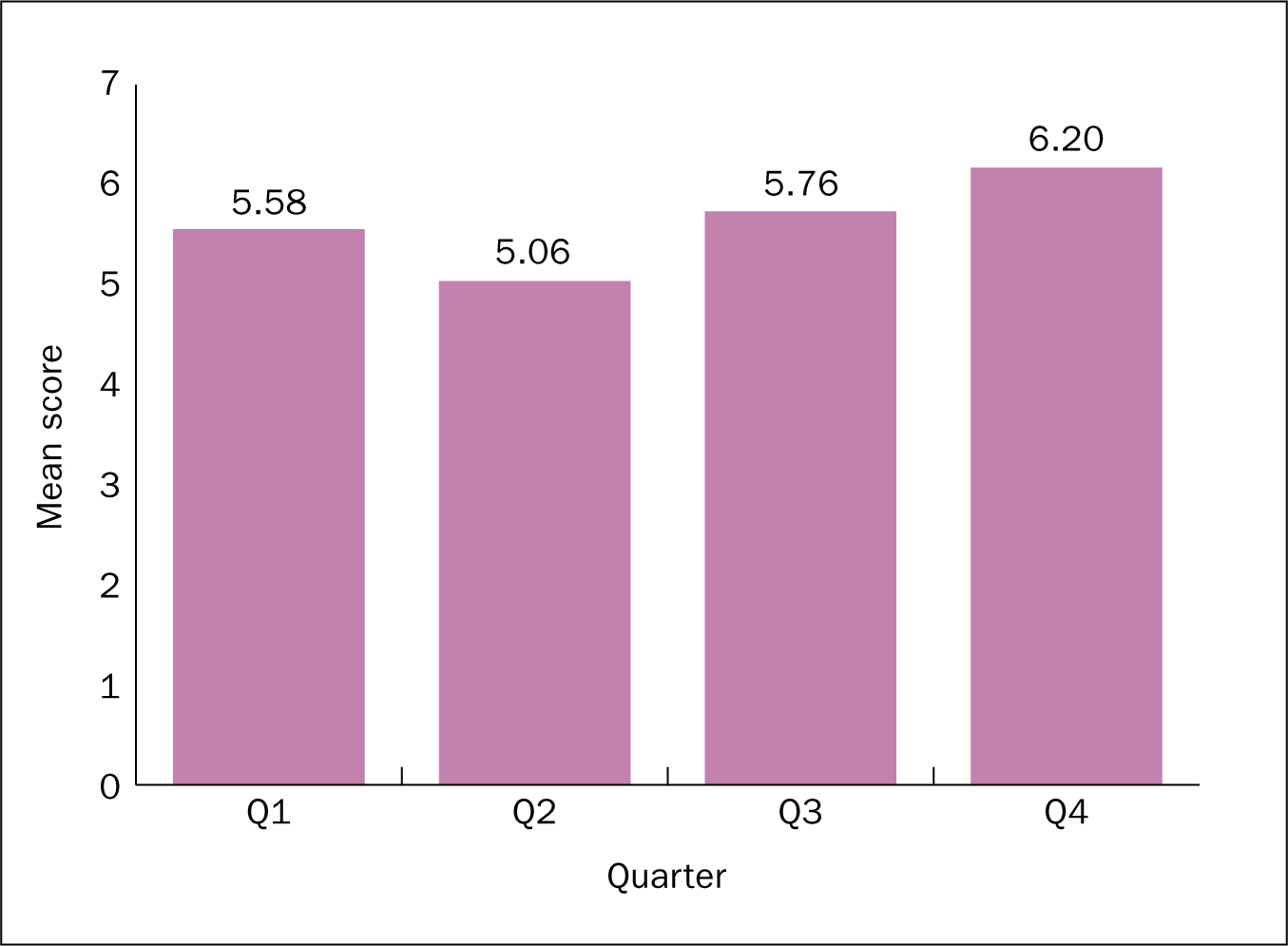

Data were compiled using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. For each quarter, a mean score of the variables was collated (Table 3). A mean increase trend can be seen through the four quarters, although this is slight (Figure 1).

| Quarter 1 | Quarter 2 | Quarter 3 | Quarter 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean variable score | 5.58 | 5.06 | 5.76 | 6.20 |

| Total number of patients | 36 | 39 | 48 | 45 |

To evaluate any statistical significance, a t test was completed of the mean score between quarter 1 and quarter 4 and is shown in the descriptive statistics in Table 4 and Table 5. A t test is used to compare two variables or scores in order to understand whether there is any significance between them. A result of < 0.05 suggests there is significance between the two groups (Gray, 2013). The result would indicate there was no statistically significant increase from quarter 1 to quarter 4.

| Quarter | n | Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 variables added together | January–March | 36 | 5.58 | 1.873 | 0.312 |

| October–December | 46 | 6.20 | 2.334 | 0.344 |

| 12 variables added together | Significance (2-tailed) |

|---|---|

| Equal variances assumed | 0.203 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 0.191 |

Discussion

The findings of the audit show that, although there was a slight increase in the mean average from quarter 1 through to quarter 4, there was no statistically significant increase in maternity staff's compliance with the Trust maternal sepsis guideline, as documented in the maternity notes. This would suggest that the maternal sepsis training package, which was provided from 1 April – 30 September 2013 (quarters 2–3), had only a limited impact.

This could be affected by two main elements. The first is that the training package may not have been implemented for long enough to have made a lasting impact. The second is that the training package may not have been effective enough, either in content or presentation, to have an impact.

Limitations

The study size could be viewed as a limitation when considering a powered sample size and any specific link to the training package. Any further studies would benefit from a larger sample, as well as a benchmark against which to consider the findings.

Conclusion and implications for practice

The findings of this audit are not easy to accept, especially given that training such as the maternal sepsis training package took a great deal of time, energy and finance to achieve. Either, or both, of the elements that could have influenced the results indicated that reassessment of the training is needed.

When an initiative that initially seemed promising starts to deliver mediocre results, value for money needs to be assessed. Reassessing services in the true interest of quality care and the safety of patients and service users must always be the priority.