According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021), the number of caesarean section births continues to increase globally, accounting for more than one in five (21%) of all births (Betran et al, 2021). This proportion is expected to increase over the next decade, with almost a third (29%) of all births likely to occur via caesarean section by 2030 (Betran et al, 2021).

A caesarean section can be crucial in situations such as prolonged or obstructed labour, fetal distress or when the fetus is in an abnormal position; however, not all caesarean sections performed are necessary for medical reasons (WHO, 2021). Unnecessary surgical procedures can be dangerous, both for the woman and her baby. As for all types of surgery, caesarean sections can have risks, including the potential for severe bleeding or infection, slower recovery time after birth, delays in breastfeeding and early breastfeeding initiation and increased chances of complications in subsequent pregnancies (WHO, 2021).

Preference for caesarean section

Many countries, including Indonesia, have shown increasing rates of caesarean section for non-medical cultural reasons, with limited consideration of how this can impact the mother and baby, in both the short- and long-term (Tribe et al, 2018). In Indonesia, as in other regions globally, cultural elements can impact opinions about childbirth, including considerations relating to social status, the desire to appear ‘modern-thinking’, safety, convenience and control.

Caesarean sections may be seen as more fashionable or esteemed compared to vaginal births. This perception is linked to social standing and financial prosperity, with caesarean sections seen to indicate a higher socioeconomic position because of the associated cost and the need for more specialised medical resources. This phenomenon has been noted in multiple studies, and research suggests that socioeconomic inequalities substantially impact the prevalence of caesarean sections in Indonesia (Lazasniti et al, 2020; Nastiti et al, 2022). Additionally, if prominent figures, such as celebrities, choose to have a caesarean section, the general population may perceive this as a more fashionable or preferable choice (Nastiti et al, 2022).

As a result of modernism and technological progress, caesarean sections may be perceived as more contemporary or technologically sophisticated in comparison to vaginal births. In a society that values technology and modern practices, this can be perceived as a demonstration of progress and innovation (Nastiti et al, 2022). Some may believe that caesarean sections are inherently safer or less risky than vaginal births, although this is not universally true, which may be preferable, particularly for those who have had adverse experiences of vaginal birth (Muula, 2007).

The perception that caesarean sections provide greater authority and reliability (Lazasniti et al, 2020) may influence the desire to have a caesarean section. The capacity to schedule a caesarean section gives individuals a sense of agency in determining the time of birth. This may be attractive to individuals with hectic schedules or specific planning requirements, as it reduces uncertainty around the birth (Lazasniti et al, 2020; Nastiti et al, 2022). In addition, despite the surgical nature of caesarean sections and the associated hazards, the operation may be seen as less painful than vaginal births because of the use of anaesthesia. This may encourage those who are apprehensive about the discomfort associated with childbirth to request a caesarean section (Lazasniti et al, 2020).

Risks of caesarean section

The growing perception that caesarean sections are preferable may not always align with medical best practice and contributes to increased rates of unnecessary caesarean section. Caesarean birth is associated with a greater risk of respiratory morbidity and higher cardio-metabolic risks in babies (Tribe et al, 2018). A meta-analysis by Słabuszewska-Jóźwiak et al (2020) found that babies delivered by caesarean section may have a higher risk for respiratory illnesses, such as respiratory tract infections, asthma and child obesity. Additionally, maternal mortality and morbidity is higher for caesarean section births than vaginal births (Zandvakili et al, 2017). Women with a history of caesarean section are at increased risk of physical consequences such as uterine rupture, mal-placentation and ectopic pregnancy (Sandall et al, 2018). There are also emotional and psychological consequences to having a caesarean section. Compared with women who had a spontaneous vaginal birth, women who had an emergency cesarean section more often report symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress at 6 months postpartum (Skov et al, 2022).

The role of midwives

To respond to the higher risks associated with caesarean sections, the WHO (2021) suggests implementing a care model primarily managed by midwives as a strategic approach to reduce the rate of caesarean sections. Midwives are globally recognised as primary maternal healthcare providers who have the critical expertise to support, enable and enhance normal childbirth (International Confederation of Midwives (ICM), 2024a). In particular, midwifery philosophies differentiate them from other healthcare providers. Midwifery philosophies established by the ICM have been adopted globally to optimise midwifery care, and are outlined in Table 1. Promoting, pursuing and maintaining physiological childbirth aligns with midwifery philosophy. Since 2016, the WHO (2016; 2018; 2022) has released guidance on ensuring positive experiences during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum.

Table 1. Philosophies of midwifery care

| International Confederation of Midwives (2024b) philosophies of midwifery care | Indonesian philosophies of midwifery according to the Indonesian Midwives Association (2024) |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy and childbirth are normal physiological processes | Pregnancy and childbirth are natural processes and not diseases |

| Pregnancy and childbirth are valuable experiences that profoundly impact women, their families and society | Every woman is a unique individual who has rights, needs and desires |

| Midwives are the most appropriate healthcare professionals to help mothers give birth | The primary function of the midwife is to strive for the welfare of the mother and baby; physiological processes must be respected, supported and maintained |

| Midwifery care promotes, protects and supports reproductive and sexual health rights and respects cultural and ethnic differences | Through communication and counselling, women must be empowered to make decisions about their health and families |

| Midwifery care is holistic and sustainable, built on understanding women's social, emotional, cultural, spiritual, physical and psychological experiences | Midwifery places women as partners, and requires a holistic understanding of women as a unit of physical, psychological, emotional, social, cultural, spiritual and reproductive experiences |

Evidence has shown that ‘being with woman’ is an important element of the midwifery model of care (Bradfield et al, 2018). The social model of care (Walsh, 2012), which is related to the midwifery and holistic models (Davis-Floyd, 2011), views humans as holistic creatures able to adapt and adjust to everything that happens in the body (Davis-Floyd, 2011; Walsh, 2012). Women who receive continuous midwife-led care are more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth (Sandall et al, 2024). Hanahoe (2020) highlighted that there is a low incidence of caesarean sections among low-risk pregnant women who receive midwife-led maternity services. Decreased rates of caesarean section can be achieved by providing continuity of care, high-quality antenatal care and support during labour and birth from a dedicated team of midwives. However, applicability may vary depending on the healthcare system, cultural norms and resources available across different settings. The availability of midwives, access to antenatal care and support services during labour and birth may differ between countries or regions (Hanahoe, 2020).

Model of care and mode of birth

Understanding the relationship between the midwife-led care model and mode of birth is essential to establishing whether this model promotes physiological childbirth, thereby reducing the caesarean section rate. Studies that have investigated the relationship between practice models and type of birth have reported varying results. Some found that the midwife-led model positively impacts birth, resulting in lower rates of intervention and increased spontaneous vaginal births compared to obstetric care, standard care or hospital birth (Cheung et al, 2011; Grigg et al, 2017; Souter et al, 2019). However, Kearney et al (2017) reported that there was no association between model of care and mode of birth.

A meta-analysis by Hoxha et al (2023) found that midwifery involvement in care was associated with consistent and significantly lower chances of caesarean birth. This could be attributed to midwives' preference for and expertise in facilitating physiologic birth. This review was conducted to explore the relationship between the midwife-led care model and mode of birth, with the intention to assess the impact of implementing midwife-led care as a primary approach in maternal healthcare.

Methods

A systematic review is the best approach to determine the most effective intervention/treatment in clinical decision-making (Harvey and Land, 2017). This method follows explicit, rigorous and systematic procedures to achieve comprehensive identification, assessment and synthesis, eliminate the possibility of bias during the research process, and increase strong and rational forms of scientific evidence (Bowling, 2014; Harvey and Land, 2017). This systematic review and meta-analysis followed six essential steps (Harvey and Land, 2017): developing the research question, determining eligibility criteria, performing a literature search, assessing the quality of selected literature, and then extracting and analysing data.

Research question

The PICO guidelines were used to generate the research question (Higgins and Green, 2011). In this study, PICO was defined as:

- Population: women who gave birth (regardless of settings or gravidity)

- Intervention/treatment: midwife-led care model

- Comparison/control: standard/conventional care (any other model of care)

- Outcome: mode of birth/choice of mode.

The eligibility criteria are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | |

| Quantitative research, both observational and experimental | Best method to assess relationship between management/intervention and outcome (Bowling, 2014) |

| Year of publication: 2010–2023 | The World Health Organization (2021) recorded global caesarean section births from 2010 |

| Full text available | To conduct a comprehensive review |

| Published in Indonesian or English | To avoid misunderstanding/mistranslation |

| Open Access | To explore articles published on databases that the authors did not have access to |

| Exclusion | |

| Studies that assessed association between midwife-led model and birth plan | Study aimed to explore births that had already taken place rather than those in the planning stages |

Search strategy

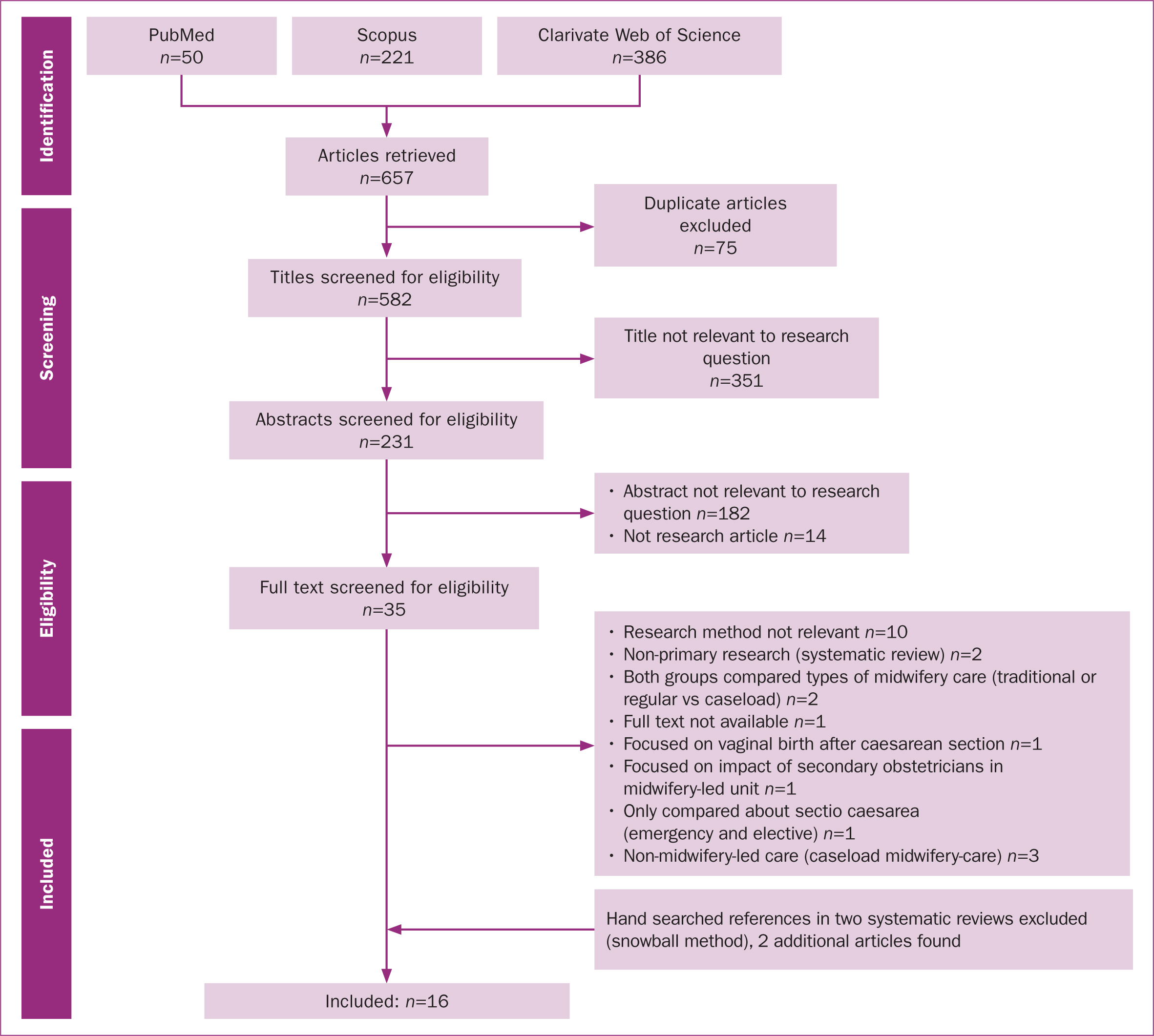

The search explored three databases: PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The search process is shown in Figure 1. The key terms used were: mode of delivery OR choice of a mode of birth OR mode of birth OR type of childbirth OR method of childbirth OR type of deliver* OR delivery method* OR type* of birth. The results were combined using AND with another key term: midwife-led care. The keywords childbirth wom*n, parturient and wom*n giving birth were not included, as they reduced the number of articles found in the initial search.

Quality assessment

The Effective Public Healthcare Panacea Project was used to assess the quality of the included studies in this article (Canadian Health Care, 2024), and results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics and quality appraisal of included studies

| Authors and year | Aims | Methods | Setting | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin-Arribas et al, 2022 | Examine association between care received (midwifery vs obstetric) and maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with normal, low- and medium-risk pregnancies | Prospective, multicentre, cross-sectional (part of COST Action IS1405) | 44 public hospitals in Spain, 2016–2019 | Strong |

| Tietjen et al, 2021 | Compared outcomes of births planned alongside midwifery units with matched group of low-risk women in obstetrician-led units | Prospective, case–control, multicentre | Six of seven midwifery units in North Rhine-Westphalia, recruitment from Nov 2018–Sept 2020 | Strong |

| Zhou and Yang, 2021 | Explore influence of midwifery care on mode of birth, duration of labour and postpartum haemorrhage of elderly parturients | Case–control | Tongde Hospital, Zhejiang Province, China, May 2018–Aug 2019 | Weak |

| Souter et al, 2019 | Compare midwife and obstetrician labour practices and birth outcomes in women with low-risk pregnancies who gave birth in the hospital | Retrospective cohort | Singleton births of 37+0/7–42+6/7 weeks' gestation at 11 hospitals in USA, 1 Jan 2014–31 Dec 2018 | Strong |

| Mortensen et al, 2019 | Analysed relationship between midwife-led care model and maternal and neonatal health outcomes | Register-based, retrospective cohort | Singleton births at Nablus Governmental Hospital, 1 Jan 2016–31 May 2017 | Weak |

| Carlson et al, 2018 | Evaluated associations between provider type and mode of birth, including examination of intrapartum management in healthy, labouring nulliparous women | Retrospective cohort | USA academic medical center, 2005–2012 | Weak |

| Grigg et al, 2017 | Compare maternal and neonatal outcomes and morbidities associated with birth in a freestanding primary midwife-led maternity unit or tertiary obstetric-led maternity hospital in Canterbury, Aotearoa/New Zealand | Prospective cohort | Women who intended to give birth in unit/hospital, 2010–2011 | Moderate |

| de Jonge et al, 2017 | Compare mode of birth and medical interventions between broadly equivalent birth settings in England and the Netherlands | Cohort | England and the Netherlands, Apr 2008–Apr 2010 | Moderate |

| Kearney et al, 2017 | Compare mode of birth (any vaginal vs caesarean) between pregnant women accessing midwife-led group vs conventional individual antenatal care | Retrospective matched cohort | Collaborative antenatal care between local university and regional public health service, Queensland, Australia, 2013 | Weak |

| Monk et al, 2014 | Compare maternal and neonatal birth outcomes and morbidities associated with birth in two freestanding midwifery units and two tertiary maternity units | Prospective cohort | New South Wales, Australia, 1 Apr 2010–31 August 2011 | Moderate |

| Dencker et al, 2017 | Evaluate maternal and neonatal outcomes and transfer rates in large midwifery-led unit sites for 6 years | Retrospective cohort | Midwifery-led unit and consultant-led unit, 2008–2013 | Moderate |

| White et al, 2016 | Compare intended and actual vaginal birth after caesarean section rates before and after implementation of midwife-led antenatal care for women with one previous caesarean birth and no other risk factors | Retrospective, comparative cohort before and after implementation of midwife-led antenatal care | Teaching hospital, England. Two cohorts: women from 2008 (obstetrician-led) and women from 2011 (midwife-led) | Moderate |

| Jiang et al, 2018 | Determine effects of midwife-led care during labour on birth outcomes for healthy primiparas | Randomised controlled (666 primiparas in labour). Half received midwife-led care (intervention) | Child Health Hospital, Fuzhou, China, Feb 2012–Feb 2014 | Strong |

| Knape et al, 2014 | Examine association between attendance and workload of midwives with mode of birth outcomes in low-risk women in a German multicentre sample | Prospective controlled multicentre trial | Four German hospitals, 2007–2009 | Strong |

| Cheung et al, 2011 | Report clinical outcomes of first 6 months of midwife-led normal birth unit in China in 2008, aiming to facilitate normal birth and enhance midwifery practice | Part of action research project that led to unit implementation. Retrospective cohort and survey used. Data analysed thematically | Urban hospital in China with 2000–3000 births per year | Weak |

| Begley et al, 2011 | Compare midwife-vs consultant-led care for healthy, pregnant women without risk factors for labour and birth | Unblinded, pragmatic, randomised trial | Two maternity hospitals in Ireland | Strong |

Data analysis

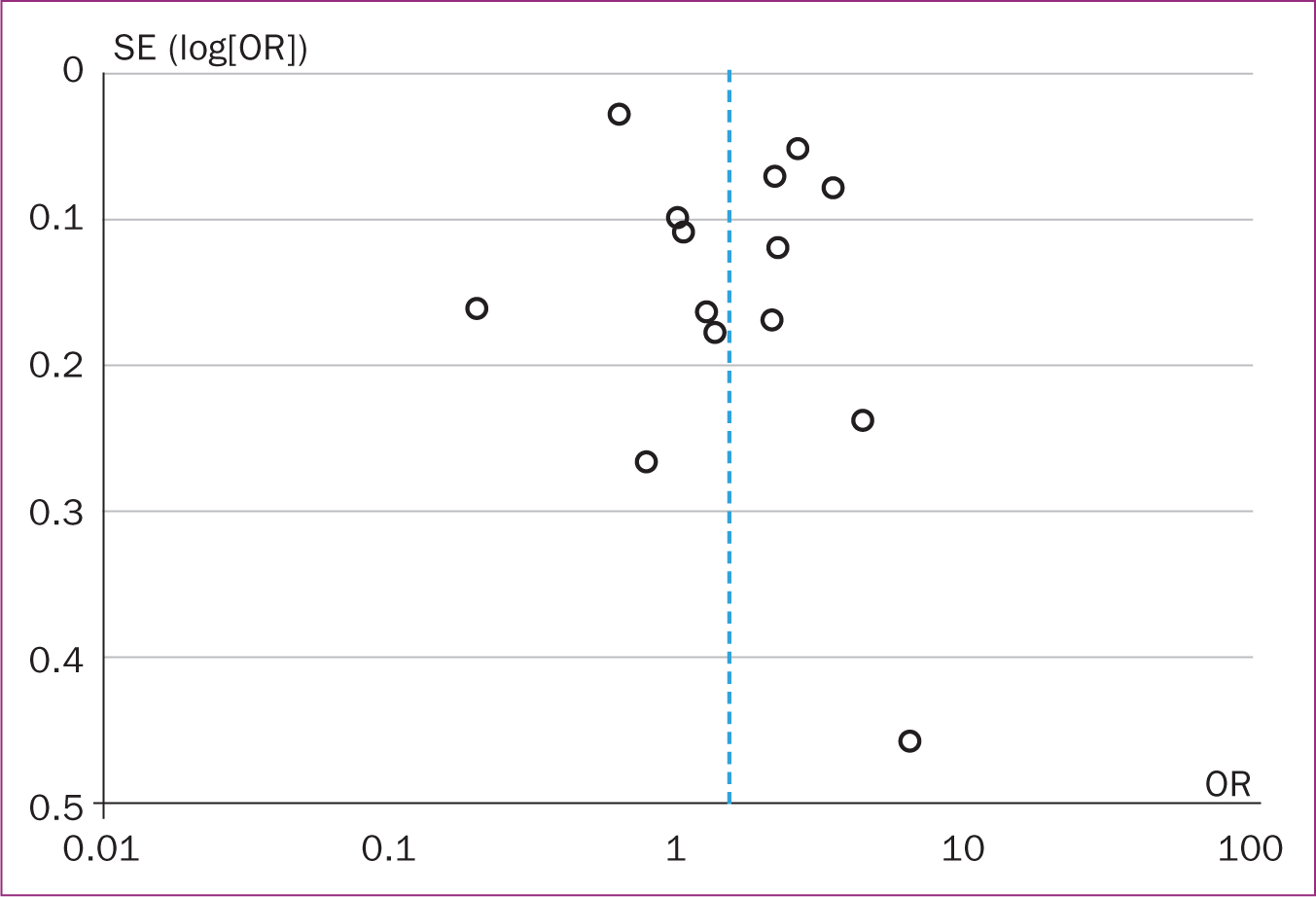

Using the Mantel–Haenszel method, a typical odds ratio estimate and 95% confidence interval were obtained. The random-effects estimator was used to assess the relationship between the midwife-led care model and mode of birth. Statistical findings >50% were categorised as having high heterogeneity. Funnel plots were used to investigate publication and other biases.

Results and discussion

Included studies

The included studies' characteristics are shown in Table 3. Two studies with experimental designs and 14 observational studies were obtained with a total sample of 125 201 people (Table 4). The studies were conducted in countries categorised by economic group: high-income countries (Australia, Spain, Germany, the UK, Ireland and the USA), upper middle-income countries (China) and lower middle-income countries (Palestine).

Table 4. Data extraction details

| Article | Total sample (midwife-led care) | Total sample (other) | Spontaneous vaginal births in midwife-led care | Spontaneous vaginal births in other care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin-Arribas et al, 2022 | 10844 | 693 | 8029 | 307 |

| Tietjen et al, 2021 | 391 | 391 | 322 | 301 |

| Zhou and Yang, 2021 | 85 | 80 | 78 | 50 |

| Souter et al, 2019 | 3816 | 19284 | 560 | 1142 |

| Mortensen et al, 2019 | 703 | 1498 | 502 | 1062 |

| Carlson et al, 2018 | 590 | 749 | 521 | 639 |

| Grigg et al, 2017 | 407 | 285 | 318 | 177 |

| de Jonge et al, 2017 | 37887 | 19096 | 2706 | 2021 |

| Kearney et al, 2017 | 110 | 330 | 28 | 73 |

| Monk et al, 2014 | 494 | 3157 | 400 | 2044 |

| Dencker et al, 2017 | 2410 | 1474 | 1878 | 900 |

| White et al, 2016 | 405 women with one previous caesarean section | |||

| Jiang et al, 2018 | 648 | 331 | 297 | 255 |

| Knape et al, 2014 | 999 | 810 | ||

| Cheung et al, 2011 | 226 | 226 | 196 | 133 |

| Begley et al, 2011 | 1101 | 552 | 761 | 372 |

Although many of the included studies were carried out in high-income countries, the results could be used as a basis for developing policy in lower-income countries. It is important to provide support for optimising spontaneous vaginal birth, particularly in resource-limited settings, as this will improve maternal and neonatal outcomes, as well as have financial benefits. A physiological birth usually does not require special facilities or complex maintenance, making services more affordable for the community and healthcare facility (Negrini et al, 2021). Additionally, the medical risks arising from non-physiological birth can be minimised and the risks of postnatal care are more manageable than in other models of care (Iida et al, 2014; Hua et al, 2018).

Statistical findings

The midwife-led care model was shown to support spontaneous vaginal birth (odds ratio: 1.57, 95% confidence interval: 1.00–2.46, P=0.05) when compared to other models of care. The heterogeneity test indicated that I2=99%; hence, the random-effects model was assumed in the analysis. This meant that the observed estimates of treatment effect varied as a result of of real differences in the treatment effect in each of the included studies, as well as because of sampling variability. The impact of midwife-led care was not only in reducing the number of caesarean sections but also in shortening the duration of labour, reducing anxiety and depression and increasing the satisfaction of women giving birth. Zhou and Yang (2021) highlighted that for women aged over 35 years, the midwife-led model gave women a better understanding of the benefits of vaginal birth, and increased their self-confidence and psychological resilience. Midwives play a crucial role in promoting and facilitating vaginal birth, contributing to the health and safety of both mother and baby during the childbirth process.

There was a positive correlation between the degree of asymmetry and the risk of considerable bias in the meta-analysis. The x-axis intercept in a symmetrical funnel plot should be around 0 but may vary significantly in an asymmetrical funnel plot. The asymmetry of the funnel plot revealed the presence of publication bias, as shown in Figure 2.

Model of care used

Many terms were used to describe the care model in the included studies. The term ‘midwife-led care’ was most frequently used (Cheung et al, 2011; Knape et al, 2014; White et al, 2016; Kearney et al, 2017; de Jonge et al, 2017; Jiang et al, 2018), as well as the similar term ‘midwife-led models of care’ (Jiang et al, 2018; Souter et al, 2019; Mortensen et al, 2019; Tietjen et al, 2021). Three articles examined ‘freestanding primary level midwife-led maternity units’ (Monk et al, 2014; Grigg et al, 2017; de Jonge et al, 2017), and two used ‘alongside midwifery units’ (Jonge et al, 2017; Tietjen et al, 2021). Other studies used the term ‘midwife-led continuity model of care’ (Mortensen et al, 2019) and ‘midwife-led units’ (Begley et al, 2011; Dencker et al, 2017). Although the terminology used varied, the critical component of care were led by midwives during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum, either independently or collaboratively with midwives and other healthcare professionals, to optimise maternal and neonatal outcomes in primary or hospital settings.

Midwives' role in promoting physiological birth

Midwifery-led care increases the likelihood of vaginal birth mainly because midwives are equipped with an in-depth understanding of the anatomy and physiology of pregnancy and childbirth (ICM, 2019). Critical components of midwifery care include respectful and woman-centred care, clinical competence, communication and support, advocacy and empower ment, cultural competence and collaboration in the healthcare team (ICM, 2019). The WHO (2016; 2018) highlighted the significance of midwives providing continuous emotional support to women during labour and childbirth, contributing to a positive birth experience. This underscores the essential role and competency of midwives in improving vaginal childbirth.

In Indonesia, midwifery competencies are regulated by the Ministry of Health (2020); the standards of competency describe the knowledge, attitudes and skills that midwives must have. Competence in midwifery is a multifaceted concept encompassing knowledge, clinical skills, emotional support, evidence-based practice, holistic care and collaboration in healthcare teams. These competencies underscore midwives' essential role in promoting and facilitating normal childbirth for the wellbeing of mothers and infants.

Implementing midwifery-led care

McLachlan et al (2012) suggested improving the adaptation, development and regular evaluation of the midwifery-led care model. Dencker et al (2017) supported training and development for midwives, as well as continuous evaluation and research into the effectiveness of midwifery-led care in improving pregnancy outcomes, interdisciplinary collaboration and empowerment for women and their families. Jiang et al (2018) promoted education and training for midwives, along with advocacy for midwifery development, community awareness and engagement on the importance of midwifery-led care. They also highlighted the importance of working collaboratively with other healthcare professionals, and the need for research and development into the benefits of midwifery-led care for vaginal birth (Jiang et al, 2018).

Tracy et al (2013) suggested collaborating with stakeholders to help implement the midwifery-led care model in clinical settings, promote staff engagement and support, and expand the model to diverse settings. Begley et al (2011) highlighted the risks of unnecessary medical interventions and encouraged midwifery practice that focused on the mother's needs, while developing transfer criteria during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum that could be implemented widely. They also emphasised the need for collaboration and the positive outcomes that stem from the use of the midwife-led care model.

Limitations

This review only included studies published in English and Indonesian, meaning studies in other languages may have been missed. The majority of the studies included in the review were conducted in high-income countries, which may not represent settings with minimal resources. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the midwifery-led care model in terms of mode of birth in these settings.

Conclusions

Implementing a midwifery-led care model can optimise physiological birth and decrease the use of caesarean sections, particularly for low-risk pregnancies. Efforts should be made to optimise care, from raising awareness among midwives to advocating for stakeholder and community understanding of the benefits of this service model. It is important to note that the benefits of the midwife-led care model extend beyond specific settings, underscoring the significance of promoting and implementing this model for low-risk pregnancies in maternity care.

Key points

- The midwife-led care model has been shown to optimise physiological birth and reduce the rate of caesarean section, especially for low-risk pregnancies.

- This model emphasises the importance of personalised care tailored to the mother's needs, minimising unnecessary medical interventions.

- The studies included in this review suggest that midwife-led care not only improves birth outcomes but also enhances maternal satisfaction and reduces perinatal anxiety and depression.

- Implementation of midwife-led care requires collaboration with stakeholders to ensure its integration into clinical settings and promote awareness of its benefits.

CPD reflective questions

- How does the midwife-led care model differ from traditional obstetric-led care in terms of patient outcomes and satisfaction?

- What are the main barriers to implementing midwife-led care in diverse healthcare settings, and how can they be overcome?

- In what ways can midwife-led care reduce rates of unnecessary medical interventions during childbirth?

- How can healthcare providers and policymakers collaborate to promote the midwife-led care model in low-resource settings?