The caesarean section (CS) rate in the UK has increased substantially in the last 20 years from 13% in 1992 to 25.5% in 2012/13 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2004; Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2013). With this increase has come a change in the indications for CS, one of which has been a rise in CS for maternal request (CSMR) without medical or obstetric indication. Caesarean sections save lives, and with medical advancements in the developed world, it could be argued that CSs are safer than ever. However, the increased maternal and neonatal morbidities associated with unnecessary caesareans, and the impact on subsequent pregnancies should not be underestimated (Lauer et al, 2010). In 2011, NICE added to their guidance for women requesting CS, that if after discussion and support, a vaginal birth is not acceptable, elective CS should be offered (NICE, 2011a). This article will explore the care of women who request CS and critically analyse the challenges and barriers that may be faced when leading developments in maternity services within the NHS. The implementation of a midwifery-led care pathway is proposed.

Caesarean section for maternal request without medical indication

The proposed care pathway is a strategy to reduce CSMR, while ensuring women are receiving holistic and evidence-based care. The World Health Organization (WHO) (1985) recommends a CS rate of 10–15%. However, the CS rate increased to 25.5% in England in 2012–13, of which approximately 40% were elective (planned in pregnancy for a specific medical or obstetric indication) and 60% were emergency CSs (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2013). It is estimated that 7% of CSs are for maternal request, with double the number of women initially requesting a CS. To what extent this has contributed to the rising CS rate is difficult to quantify as various studies have differing definitions of CSMR. It could be argued that a woman who had a previous forceps delivery and wants a CS in the subsequent pregnancy is a CSMR for previous traumatic birth experience. The incidence of CSMR in developed countries ranges from 1.5% to 28% of all CS (Thomas and Paranjothy, 2001). It is important to establish why women are requesting CSs without medical indications (NICE, 2011a). The majority of women identify common concerns in pregnancy, but 6–10% of women report a disabling fear of labour or childbirth known as tocophobia (Fisher et al, 2006). Reasons for primary tocophobia may include fear of pain, obstetric or pelvic floor injury, emergency CS, being left alone in labour or loss of control. This may be associated with previous trauma, abuse or mental health issues (Nerum, 2006). Secondary tocophobia stems from a negative experience in a previous labour and birth. As a result, women may experience increased stress and nightmares, request CS or avoid pregnancy (Melender, 2002; Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013). Robson's (2008) study found the most common reason for requesting a CS was concern about the risks of a vaginal birth to the baby. This highlights a perception that CSs are the safest mode of birth for babies, despite evidence that a CS rate over 13–15% is not associated with a decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality (Jonsdottir et al, 2009; Lauer et al, 2010).

Risks and benefits of caesarean section

The risks of CS have decreased in recent years with the introduction of routine antibiotics, improved anaesthetic and surgical procedures and thromboprophylaxis (Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013). Women should be informed that a planned CS is associated with a significantly increased risk of hysterectomy (RR 95.5 (95% CI 67.71–36.9) caused by postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) (Stanco et al, 1993), cardiac arrest, a longer stay in hospital and neonatal admission to intensive care units. Planned CSs are associated with a decreased risk of perineal and abdominal pain during birth and postpartum, injury to the vagina and obstetric shock (NICE, 2011a). Research findings are not always transferable to CSMR, as studies may have combined emergency and elective CSs or CS for medical indications (Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013). It is well documented that the risks of elective CS are less than those of emergency CS (Villar et al, 2006). However, risks are primarily focused on short-term outcomes with little evidence on long-term outcomes.

The Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE) comment that psychological issues that arise in, or are related to, pregnancy can contribute substantially to a woman's wellbeing even years after the pregnancy is over (Cantwell et al, 2011). It is important to discuss the impact of primary CS on morbidity and mortality in subsequent pregnancies. The increased risk is of abnormal placentation (e.g. placenta accreta, increta and percreta) and placental abruption which significantly increases the risk of PPH, blood transfusion and hysterectomy (Gilliam, 2006). Despite a large number of studies on the risks of CS, the current data is of low quality with no evidence from randomised controlled trials and many studies report conflicting results.

Management of CSMR

The care offered to women requesting CSMR varies widely in practice (NICE, 2011a). NICE (2011a) suggests strategies that could impact women's chosen mode of birth these include;

However, there is little evidence to support or discount these interventions and no established clinical practice on how to care for women with fear of childbirth who request a CS (NICE, 2011a). A review and analysis of the evidence highlighted the urgent need for further research in this area as the limited research available was of low quality with small sample sizes. NICE (2011b) suggests offering women with high levels of anxiety a 1 hour session with a midwife, and a 3 hour session with a clinical psychologist. Women with low level anxiety are offered 1- or 2-hour long sessions with a midwife. This recommendation is based on expert clinical opinion rather than research findings. Inclusion of sessions with a clinical psychologist was considered for the pathway. However, because this is not a research-based suggestion, the current evidence on alternative psychological interventions was evaluated.

A small study of 33 women who requested CSMR found that by discussing women's fears and offering counselling, half the number of women converted to plan a vaginal birth (Ryding, 1993). Another study randomised women to receive either CBT or usual care. In both groups, 62% of women who originally requested CS converted to vaginal birth and fewer women in the CBT group who had vaginal births reported fear of pain in labour and had shorter labours (Saisto et al, 2001). A Norwegian cohort study established a multidisciplinary team including a senior midwife, obstetrician, and a social worker to counsel and support women antenatally. It was significantly effective in avoiding CS (86% converted to planning a vaginal birth post intervention) and increasing maternal satisfaction. However, the sample of 86 women was relatively small and not randomised, making results difficult to generalise (Nerum, 2006).

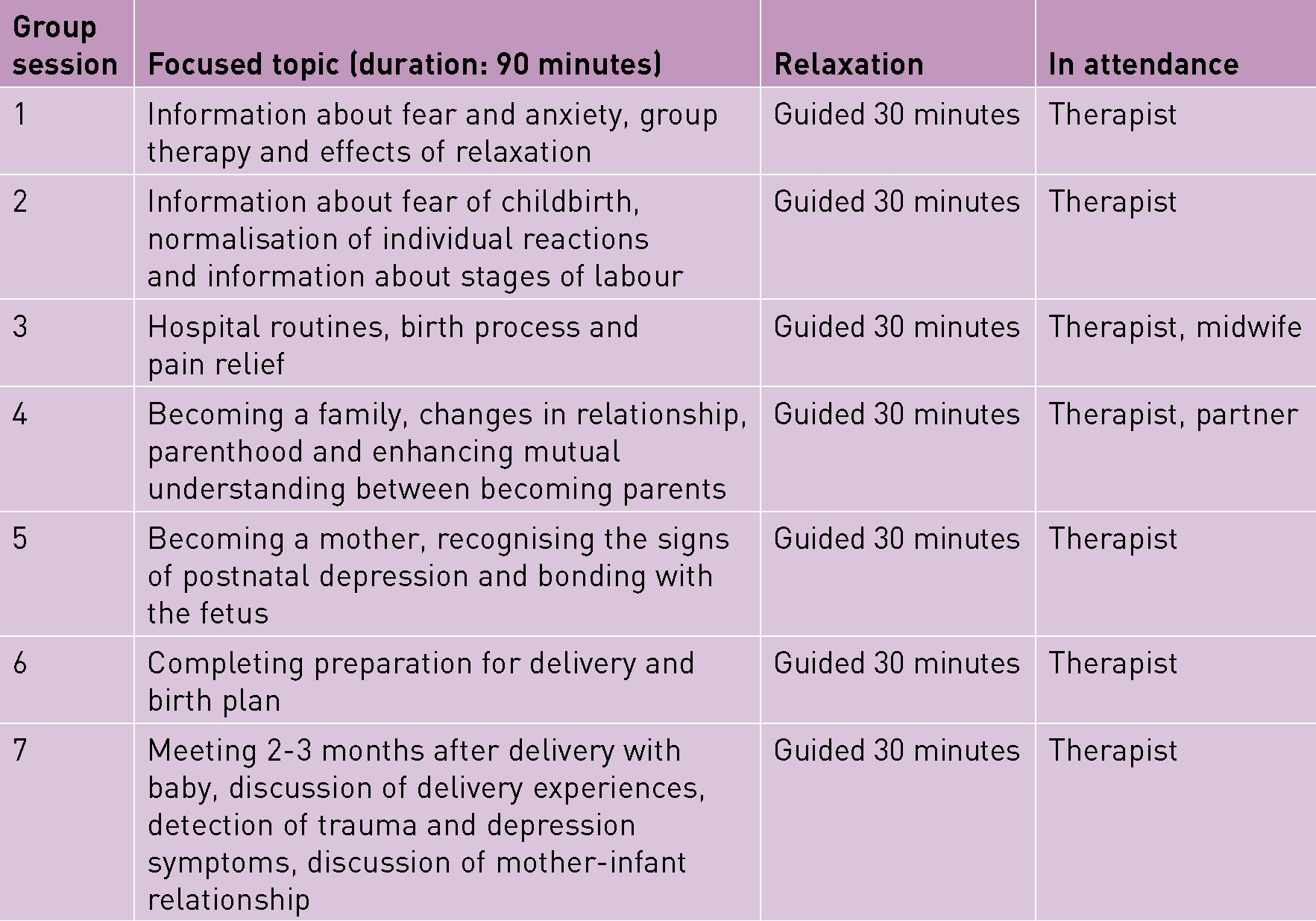

Psychoeducational groups, based on the principles of CBT, are low-intensity interventions which have been found to decrease anxiety and depression in cases of generalised anxiety disorder (Kitchiner et al, 2009). A Finnish study compared group psychoeducation for women who request caesarean section, which consisted of six 2 hour group sessions with a psychotherapist, and a control of the standard care of two appointments with an obstetrician. The psychoeducation was led by a psychologist and included discussions, visualisation and relaxation exercises. Significantly more women in the experimental group chose a vaginal birth (82.4% vs 67.1%; P=0.02) (Saisto et al, 2006). A randomised controlled trial supported these findings and evaluated whether similar group psychoeducation therapy versus conventional care affected outcomes in women with severe tocophobia, and found a reduction in CSMR, emergency CS and negative birth experiences (Rouhe et al, 2013). Accordingly, a referral for psychoeducational therapy is included in the care pathway, as based on the current available evidence; it is effective in reducing CSMR and increasing birthing satisfaction (Rouhe et al, 2013).

The vision

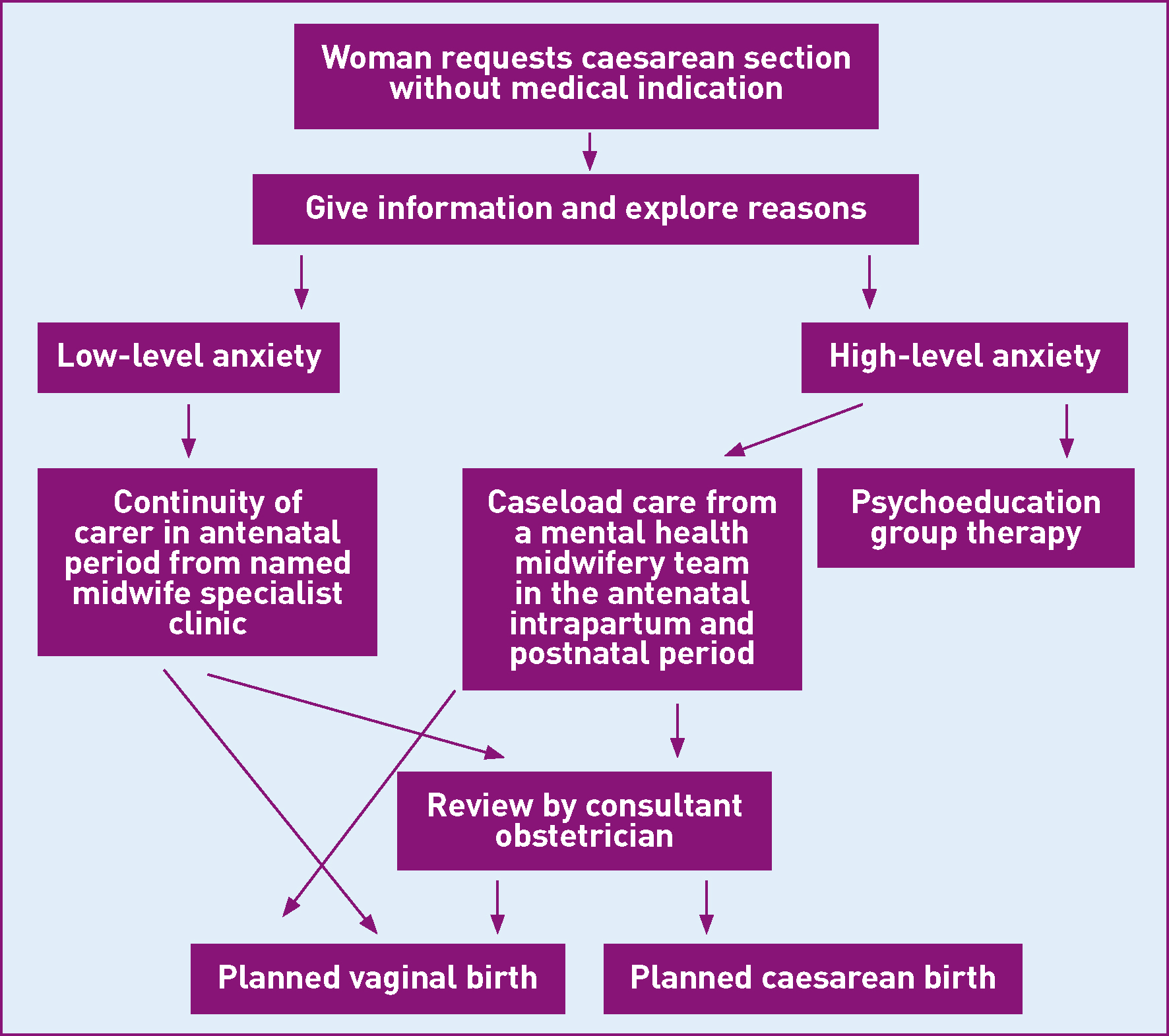

Midwives are experts in caring for women with uncomplicated pregnancies and view pregnancy and childbirth as a normal, physiological life event, placing confidence in women's ability to give birth naturally (Sandall et al, 2013). It could be argued that obstetricians primarily care for women with complicated pregnancies and may view pregnancy as a medical condition (Bewley and Foo, 2011). Therefore, midwives are well equipped to support women and normalise birth. Midwifery-led care has been shown to increase spontaneous vaginal birth and improve satisfaction (Hatem et al, 2008). A care pathway, coordinated by midwives, would create a process through which all women requesting CS would be offered interventions with the aim of reducing unnecessary CS, overcoming fears and increasing satisfaction. In addition, the pathway which has been developed for this service (Figure 1), facilitates continuity of midwifery care which has been shown to increase women's sense of control and improve birth experience (Sandall et al, 2013).

Care pathway

Barriers to change

Political

In July 2010, the coalition government announced its radical plans to reform the NHS through the Health and Social Care Act, 2012 and embarked on the biggest restructure since its creation in 1948. Concerns have been raised that the reforms allow for private sector providers to bid for contracts, further creating a ‘market’ which could destabilise health economies and fragment patient care (Pollack, 2005). During this time of great change, the NHS needs leadership and management at all levels within the NHS and across NHS boundaries (The King's Fund, 2011). The ‘Friends & Family Test’ was implemented in maternity services in 2013 in order to assess the quality of women's experiences, gain a comparable insight and support service developments (NHS England, 2013). The care pathway aims to improve women's satisfaction. Positive experiences, which are reflected by this test, are publicly recognised and consequently influence women's choice of care provider. This pathway is also supported by policies emerging recently which have a noteworthy emphasis on mental health and want improved outcomes for mental health services (NHS Commissioning Board, 2012).

Economic

The Government has determined that the NHS must save £20 billion by 2014/15 (The King's Fund, 2013a). The NHS came under criticism from politicians and was described as ‘over-managed’. Health ministers and the DH planned a 45% cut in the number of managers and senior managers (DH, 2010b), despite little evidence that the NHS is over-managed and no published analysis explaining the 45% figure (The King's Fund, 2011).

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) are expected to increase production while reducing spending (The King's Fund, 2013a). Therefore, when planning change the economic consequences must be established. NICE found planned vaginal birth was more cost-effective than elective CS, and vaginal birth £700 cheaper than CSMR. This suggests that the NHS could save £4.9 million for every percentage point reduction in CSs, although, this is a projection and does not consider all the costs of potential adverse outcomes. Based on estimates, NICE (2011b) suggests the cost of implementing mental health support for women requesting CSMR would be £2056 per 100 000 of the population per year. The cost implications of providing psychological support would be offset by the reduced cost of CS when a planned CS was changed to a planned vaginal birth (Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013).

Social

Fear is a normal response that develops human protective instincts; however, severe fear can be debilitating. The medicalisation of childbirth in Western countries plays a significant role in creating and perpetuating fear surrounding childbirth (Fisher et al, 2006). In many societies, what was once considered a women-centred natural event is increasingly seen as a medical pathology cured by medical interventions (Bewley and Foo, 2011). Birth has moved from the home to medical institutions, which further contributes to mystifying childbirth (Fisher et al, 2006). In some countries, such as Brazil, CSs may be seen as a status symbol, which higher social classes can afford to choose. The power of the media in influencing a mode of birth cannot be underestimated, and the increasing number of celebrities choosing CSMR normalises this option (Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013).

Reports such as Changing Childbirth (DH, 1993) and Maternity Matters (DH, 2007) set out the fundamental right of women to have choice in their maternity care. In view of this sustained emphasis on choice and women's experience, it could be argued that all women have the right to deliver by CS based on their preference, whether or not there is an indication (Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013). However, as the NHS is a public sector organisation financed by the taxpayers, it is not in the public interest to support a more expensive unnecessary intervention without health benefits (Bewley and Foo, 2011). In addition to the extra economic demands on the health service, higher CS rates correlate with increased maternal morbidity and mortality (Villar et al, 2006).

Although a woman may request a CS, it is the obstetrician who has to agree to perform the operation. It can be argued that when a doctor carries out a CSMR and causes avoidable harm in doing so, the woman cannot be held entirely responsible. Obstetricians, like all doctors, pledge to ‘first of all, do no harm’ (Sokol, 2013: 1). In the context of CSMR this raises ethical uncertainty for doctors when facilitating women's choice, but potentially doing more ‘harm’ than good (Bewley and Foo, 2011).

Technological

The NICE CS guideline group agreed that the most important outcomes to consider were women's experience of birth and care, mental health and satisfaction. This acknowledges the importance of mental health and women's experience in providing good care. A Cochrane review on midwife-led care found women were more likely to have a normal birth and feel in control during labour and birth (Hatem et al, 2008). Maternity Matters (DH, 2007) and more recently Midwifery 2020 (DH, 2010b), place midwives at the centre of maternity care as the lead care coordinators. A vision of how midwives can lead and deliver care in a changing environment was developed, which empowers midwives to use their positions to contribute to improving women's care (DH, 2010b). When proposing the implementation of a care pathway, key stakeholders need to be approached. These supporting documents reiterate that this is an important issue which would benefit from a midwifery-led service.

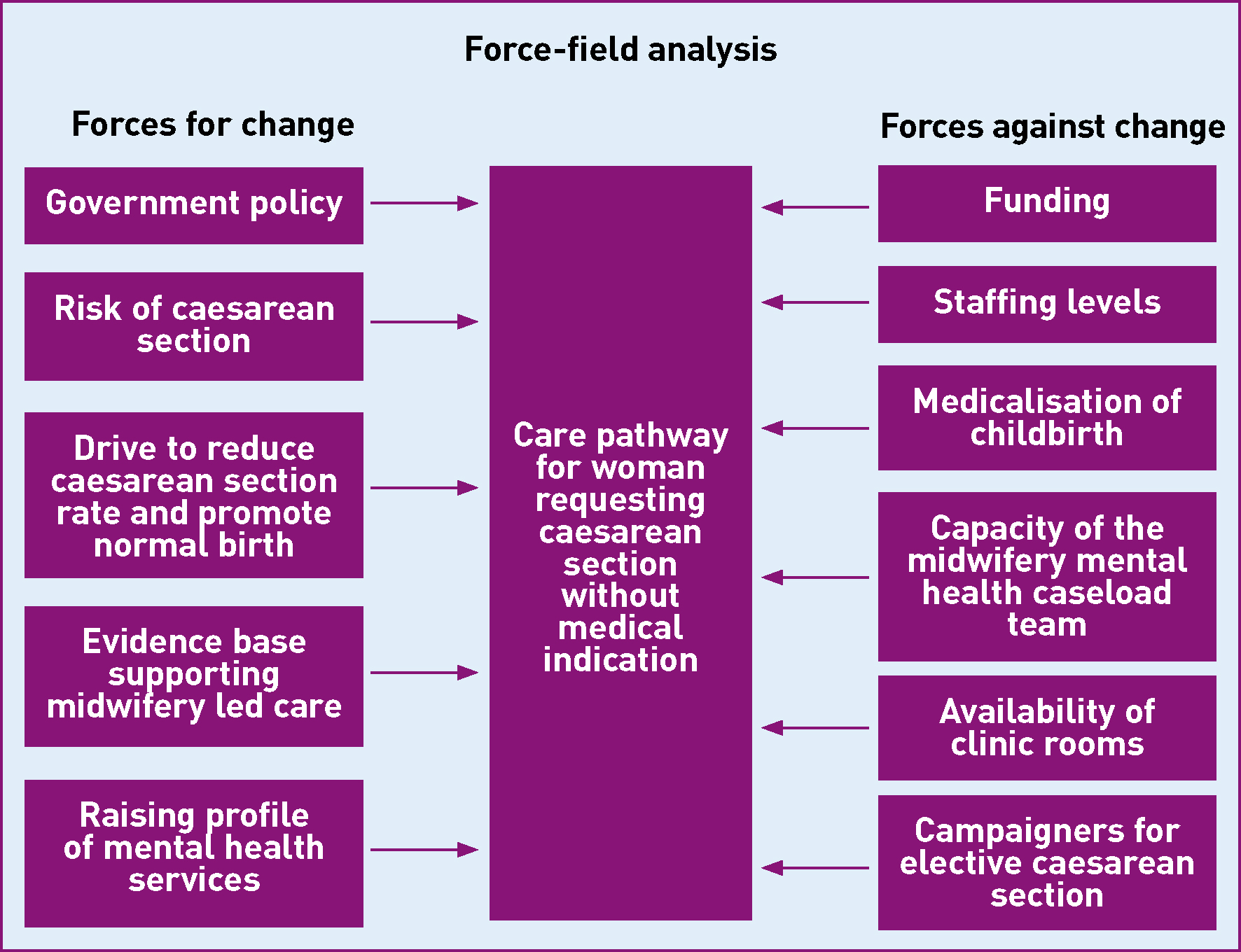

A force-field analysis (Lewin, 1948) was carried out to identify driving forces and potential barriers to change (Figure 4).

A significant driver for change is the overall consensus from supporting policies and guidance that argues for measures to reduce the high CS rate (Lauer et al, 2010). The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2006) produced a report and developed a self-improvement toolkit, which focused on promoting normal birth and reducing the CS rate. NICE (2011a) guidance supports the practice that women requesting CS due to anxiety should be referred to a perinatal mental health professional, and advises services are commissioned to reflect this.

Barriers may include the capacity of the midwifery team to care for the women with high-levels of anxiety due to limited caseload spaces. A specialist midwife would need to be appointed and salaried. Funding is needed to employ a therapist to facilitate the psycoeducational groups and a room allocated for the sessions.

When evaluating the pathway, findings may indicate that a W-DEQ score ≥100 is not an appropriate level to offer intensive support and pschoeducational therapy, which may need to be adjusted. The pathway focuses on the principle that women request CS due to anxiety surrounding childbirth. It may not be suitable for women who are not fearful of childbirth, yet prefer CS for other reasons (Souza and Arulkumaran, 2013).

Conclusion

A ‘non-heroic’ leadership style promotes leadership at all levels, not restricted to senior management roles, based on shared responsibility which benefits the service and care being delivered (Lewin, 1948). This model puts women's care at the centre, allowing staff to identify what needs doing and contribute to making a change (The King's Fund, 2011). The proposed care pathway has been developed based on this principle. CS rates are increasing and as a consequence, so are the associated morbidities. This has significant cost and health implications. A CS is deemed ‘unnecessary’ if it does not provide benefit to mother or baby (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2010). As the NHS continues to try to find ways to save money, CSMR may become a procedure which is charged for (The King's Fund, 2013b), further increasing health inequalities based on socioeconomic status.

My vision is to reduce CSMR by providing holistic care to reduce women's anxieties and improve their birth experience. Implementing a midwifery-led care pathway for women requesting a CS without medical indication ensures all women receive evidence-based care and interventions. The aim of this pathway is that women make an informed choice regarding mode of birth with an opportunity to manage anxieties.