Colleagues working in maternity services across the UK have experienced a range of challenging events over recent years, with implications for clinical governance and patient safety. This has had a significant impact on midwives, with the Royal College of Midwives (RCM, 2023) describing the current climate as a ‘midwifery workforce crisis’. Such challenges for maternity services are also reflected in the Ockenden (2022) report, and have been exacerbated by the pandemic, workforce shortages and the current cost of living crisis. National reports have published data from midwives stating that they feel exhausted, demoralised, unsupported and undervalued (RCM, 2023).

In addition to the challenging political and workforce climate for midwives, they are also at risk of exposure to traumatic situations at work, including exposure to patient death or near-death and other traumatic clinical adverse events. Midwives may be exposed to traumatic responses from those they are caring for (Leinweber and Rowe, 2010; Rice and Warland, 2013). The risk of moral injury is high, given the levels of pain and discomfort that some women and birthing people may experience to safely deliver their babies. Furthermore, midwives are required to hold a lot of uncertainty regarding clinical outcomes for the birthing person and their babies, especially for those with high-risk pregnancies.

The difficult situations and workforce challenges experienced by midwives may impact their emotional wellbeing, potentially leading to burnout, compassion fatigue, traumatic stress symptoms and psychological distress (Sheen et al, 2014; 2015; Henriksen and Lukasse, 2016; Creedy et al, 2017; Dixon et al, 2017; Hunter et al, 2019). Midwives experiencing these symptoms are more inclined to take sick leave, and some may leave their profession altogether (Sheen et al, 2015; Leinweber et al, 2017; RCM, 2023). Hunter et al (2019) found a high number of midwives in the UK experienced high levels of emotional distress and that younger and recently qualified midwives, as well as midwives with a disability, were more vulnerable to higher levels of work-related emotional distress compared to their peers.

Staff shortages can lead to colleagues feeling more burnt out and vulnerable to working longer hours with little or no breaks. This can lead to high levels of exhaustion and burnout, with implications for patient safety and the quality of care. Research suggests that doctors experiencing burnout are twice as likely to be involved in patient safety incidents (Hodkinson et al, 2022). This has significant implications for the cost of harm from clinical negligence across maternity services in the UK. NHS England (2023) reportedly spends approximately £3 billion annually for maternity and neonatal services. However, an annual report from NHS Resolution (2022) stated that the total cost of harm from clinical negligence was £13.6 billion, 60% of which was maternity claims (amounting to £8.2 billion), placing maternity services under significant financial strain.

The 3-year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services (NHS England, 2023) stated that maternity staff should feel valued and supported by the system, to mitigate staff turnover and burnout and improve patient care. Given the vulnerability that some midwives and maternity colleagues may experience with their emotional wellbeing, they may benefit from clinical supervision and staff support being built into everyday practice. This could include one-to-one and group clinical supervision, reflective practice, debriefs and other methods of support, such as trauma informed educational groups. However, the literature is limited in terms of outcomes for such provision, although there is evidence that well-supported staff are more present, productive and compassionate, which has a direct impact on the quality of care that babies and families receive (McGarry et al, 2013).

The limited published studies on models of midwifery staff support highlight the difference that such support can make in terms of protecting against traumatic stress symptoms and improving wellbeing. For example, the programme for the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder in midwifery has been successful in reducing post-traumatic stress disorder rates in midwives, as well as reducing work-related stress absences and the number of staff wanting to leave the profession (Sheen et al, 2015; 2016; Slade et al, 2018). Such findings highlight the need for staff support models to be offered to midwives as a fundamental part of their role. Nevertheless, there is currently limited provision for this across maternity services in the UK as a whole.

Clinical supervision, governance and risks

The statutory regulation for clinical supervision of midwives came to an end in 2017 and was replaced by the Advocating for Education and Quality Improvement (A-EQUIP) model. This model is led by professional midwifery advocates and aims to improve midwives' wellbeing by enhancing the quality of care for women and their families (Capito et al, 2022). This clinical governance is in place across the NHS to support delivery of the highest standard of care to patients; however, it does not cover the delivery of psychological interventions by midwives. From a clinical governance perspective, healthcare professionals using psychologically informed principles to support patients and staff require clinical supervision to ensure that they are delivering high-quality, safe care and are accountable for this (British Psychological Society, 2014). While the A-EQUIP model is invaluable for midwives and governance across the board, clinical supervision of psychological interventions is essential in ensuring the safe and effective use of psychological or therapeutic techniques, particularly given the vulnerability of the patients under the care of specialist midwives.

Without the offer of clinical supervision from a trained psychological professional, there are potentially significant risks for midwives relating to their own professional accountability and patient safety. For example, midwives using psychologically informed principles in their work may not necessarily have had formal training or the qualifications to work psychologically. This can lead to significant risk factors being missed, such as patients (or staff) who may be at risk of traumatic stress, re-traumatisation, suicidal ideation, depression and other mental health difficulties or of actually causing harm.

The authors therefore developed a novel midwifery clinical supervision service that was piloted with specific groups of midwives. As a result of challenges across the board in maternity services, the authors also set out to provide a responsive, one-to-one, confidential staff support service and ad-hoc group psychologically informed debriefs for all maternity colleagues.

Methods

This pilot study offered one-to-one and group clinical supervision to selected midwives using psychologically informed principles in their work, including midwifery colleagues who used certain types of psychological techniques to support patients. It is likely that specialist midwives are more likely to use these principles throughout their work because of the nature of the patients under their care. As such, this supervision was aimed at those offering birth choices (tokophobia) clinics, bereavement midwives, birth afterthoughts midwives, mental health midwives, fetal medicine midwives and the lead professional midwifery advocate.

The service

Funding was obtained through the local maternity and neonatal systems staff retention budget for a 12-month midwifery clinical supervision pilot. The offer under this remit was to recruit two senior and highly experienced clinical psychologists, including a consultant clinical psychologist and a principal clinical psychologist, both on a 12-month fixed-term contract. The aims were to provide clinical governance for psychological interventions delivered by midwifery colleagues who were not qualified psychological professionals and to increase work satisfaction, decrease burnout and improve overall emotional wellbeing. Sessions were offered face to face as well as online, to ensure easy access. The service model included both formal clinical supervision and staff support.

Formal clinical supervision

Clinical supervision was provided to specialist midwives for mental health, substance misuse, learning disability, birth trauma and tokophobia, as well as to the lead safeguarding midwife for mental health, bereavement midwives, birth afterthoughts midwives, lead professional midwifery advocates, fetal medicine midwives, delivery unit coordinators and consultant midwives. These groups were prioritised in order to provide governance over psychological interventions; reduce the risk of harm to patients and colleagues, including the risk of re-traumatision after a previous traumatic experience; and allow staff to learn to recognise and respond to complex trauma and know when to signpost and complete training on psychological formulation. Group or one to one clinical supervision was provided on a monthly basis.

A further part of the offer was providing consultation into the Birth Choices Clinic and Rainbow Clinic, in order to minimise risk of harm and upskill colleagues to foster the development of trauma-informed care.

Staff support

Psychologically informed debriefs were offered to all maternity colleagues. One-to-one ad hoc and ongoing staff support sessions were offered to midwives who worked on the delivery unit, maternity close observation ward, inpatient antenatal wards and fetal medicine.

Participants

This pilot recruited a purposive sample of the 75 colleagues who attended the service between June 2022 and June 2023; no further inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. Each time a colleague attended, they were sent a link to an online dataset immediately after the session. It was not a requirement to complete this in order to attend the service.

Data collection

Staff attending the clinical supervision service were asked to complete an anonymous online dataset to record their feedback and outcomes from having accessed the service. The dataset included a bespoke anonymous feedback survey developed by the authors. Given the nature of the pilot project and the limited time to undertake the project (12 months), the questionnaire was not validated or pre-tested. A variety of open and closed questions were asked on the questionnaire to capture participants' experiences of attending the service. This included questions around what helped them feel able to attend the service, as well as what barriers there were in attending. Participants were asked for their feedback in terms of what they felt would be helpful in order to improve the service further.

Two wellbeing measures were included, which participants completed at the first and last session they attended. These measures were selected to reflect similar literature where they have been used with populations of maternity colleagues (Kinman et al, 2020). The general health questionnaire (Goldberg and Hillier, 1979) was used to evaluate overall emotional wellbeing. Participants were asked to rate 12 questions on a Likert scale (0–3) that assessed the severity of a mental health issue, with a higher total score indicating worse health. The professional quality of life questionnaire (Hundall Stamm, 2009) was used to evaluate compassion satisfaction, burnout and traumatic stress symptoms. Participants were asked to rate on a scale from never to very often, how often they had particular experiences (such as ‘I am preoccupied with more than one person I help’, ‘I get satisfaction from being able to help people’). Higher total scores in each of the three subscales indicated greater satisfaction, higher risk of burnout and higher risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms respectively.

Data analysis

Paired sample two-tailed t-tests were used to test for differences between baseline and follow-up scores for the two wellbeing measures, with significance set at P<0.05. For emotional wellbeing, scores higher than 15 were categorised as ‘high risk’ of emotional wellbeing difficulties. Scores of >10 indicated risk of emotional distress. Risk categories were not used to analyse data, only to interpret the results.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the quotes provided, in line with the five essential elements from trauma literature (Hobfoll et al, 2007).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the hospital's Quality and Safety Information System (reference: ID4646; PRN10646). All participants were asked to give informed consent to take part in the study at the beginning of the questionnaire. All participants were informed that the data would be used for dissemination in peerreviewed journals.

Results

Of the 75 attendees, 47 completed the dataset, 28 of whom attended one session and 19 of whom attended more than once. For those who attended multiple sessions, only 10 submitted responses from their first and final sessions. In terms of the parts of the service accessed, eight participants attended individual clinical supervision for their own work, one attended clinical supervision for delivery of their own supervision to others, 14 attended group clinical supervision, 20 attended a psychologically informed debrief and eight attended one-to-one staff support sessions.

Of those who attended at least once and completed the survey, overall satisfaction was high. The majority (76%) reported that attending the clinical supervision service (including staff support sessions and debriefs) helped them to feel more satisfied with their job, 85% agreed that attending the service helped them to do their job more effectively and 96% said that they would like to continue attending, while 97% said that they would like the pilot to continue beyond 12 months.

Quantitative outcome measures

Need for emotional support

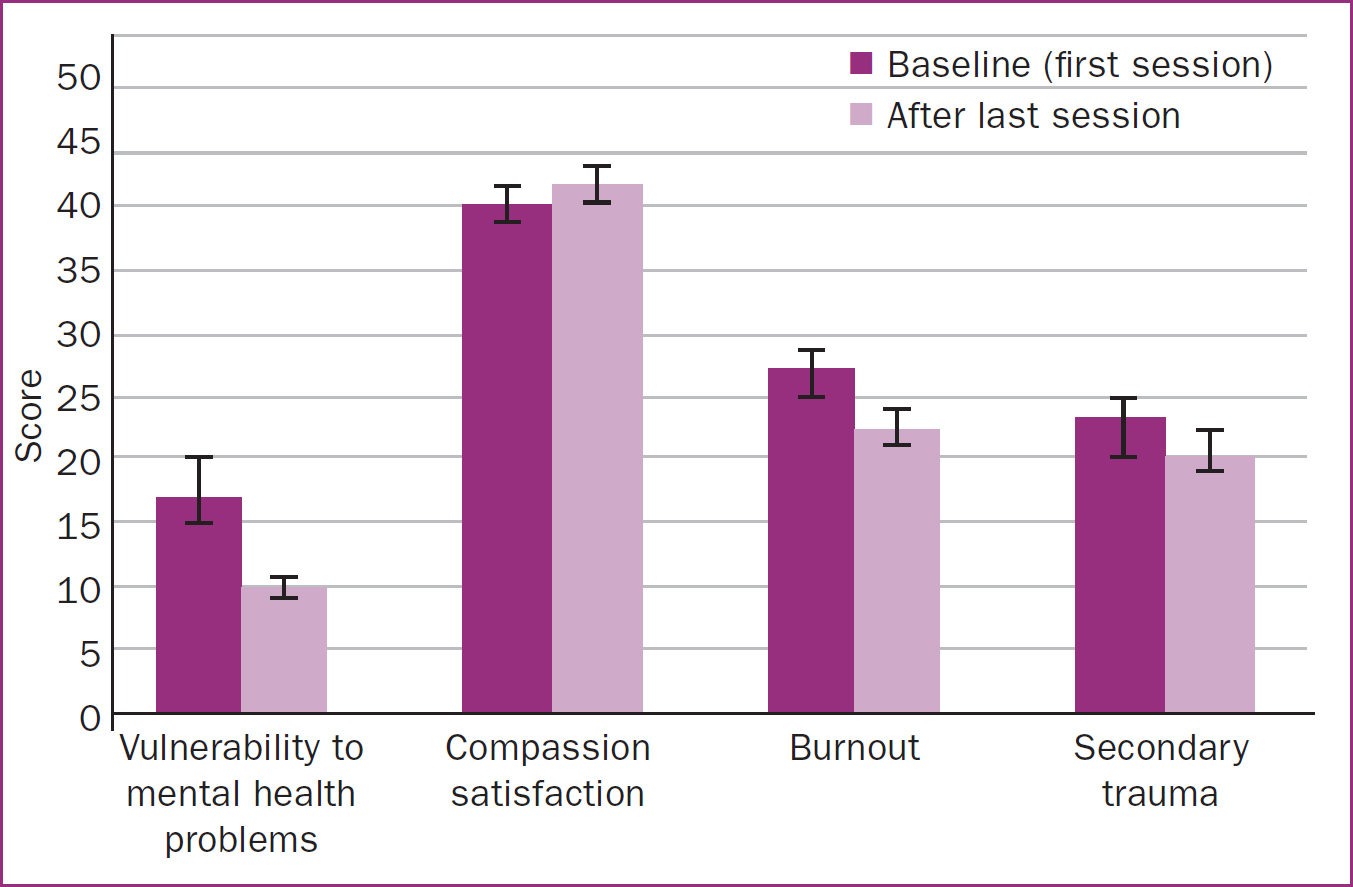

On entering the service, 75% of midwives scored above the threshold for high risk of secondary trauma, and 43% had a high level of burnout. The average score for risk of emotional wellbeing difficulties was 17.5, which is above the threshold for ‘high risk’. Only 4% had lower than threshold scores for compassion satisfaction, suggesting that midwives still had compassion for those they work with even when under significant levels of strain.

Effectiveness of the clinical supervision service

In each measure of wellbeing there was an improvement between first and last session (Figures 1 and 2). Scores for the general health questionnaire decreased significantly from baseline (P=0.016), showing significantly lower risk of emotional wellbeing difficulties on the last visit compared to their first. At baseline, the overall score had a mean of 17.5, above the threshold for risk of emotional distress. After sessions with the clinical psychologists, the mean score was 9.6.

Compassion satisfaction scores were higher at last session compared to the first, although the difference was not significant (P=0.156). Similarly, traumatic stress symptom scores were lower, but this was not significant (P=0.116) Burnout was significantly lower at the last session compared to the first (P=0.024).

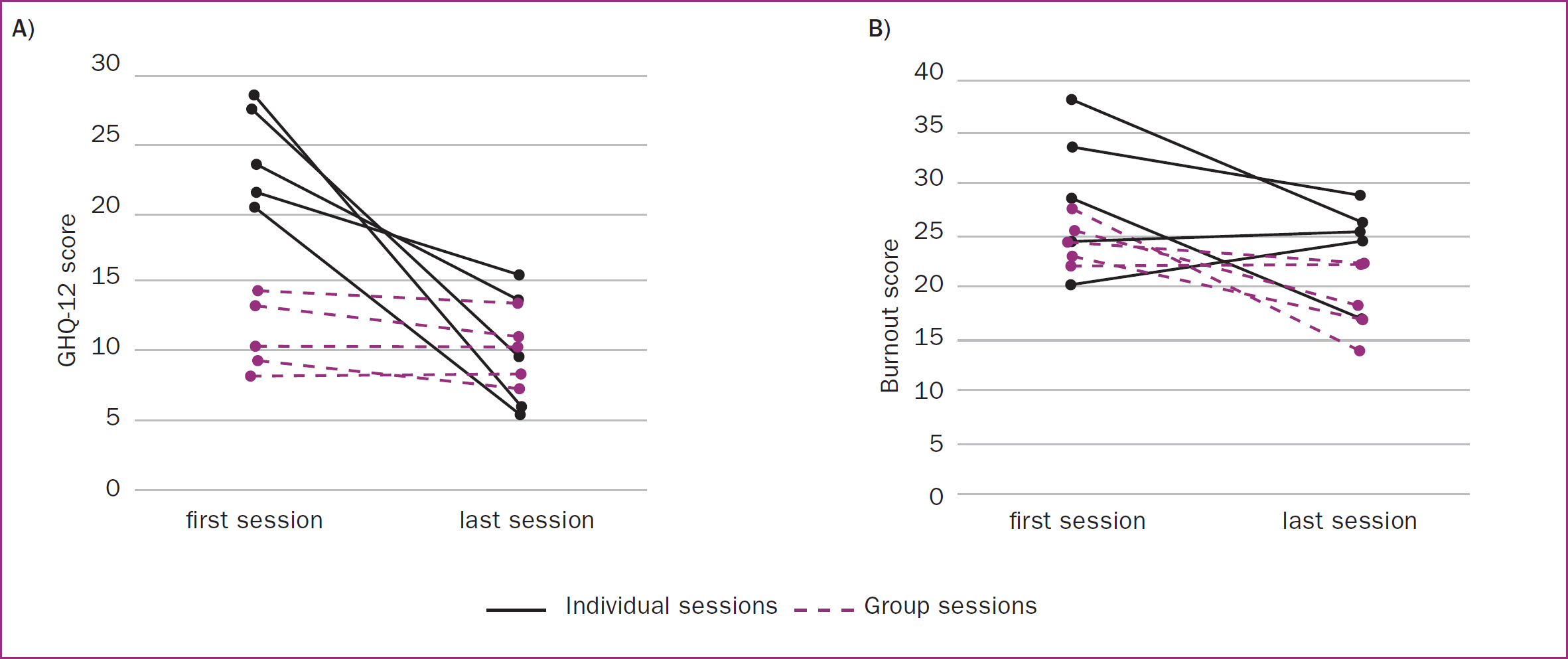

In the scores for vulnerability to emotional wellbeing difficulties and burnout, different effects were seen depending on whether group or individual treatments were sought (Figure 2). Figure 2a shows that midwives seeking one-to-one staff support sessions for wellbeing began with a particularly high vulnerability to emotional distress, and these levels dramatically reduced after attending sessions. Although midwives attending group clinical supervision sessions and debriefs did not significantly improve in terms of their emotional wellbeing, they had all been under the clinical cut-offs for vulnerability to emotional distress difficulties to begin with, and did significantly reduce their levels of burnout from baseline (Figure 2b). These results suggest that group clinical supervision sessions and psychologically informed debriefs, as well as one-to-one staff support sessions, are invaluable in improving emotional wellbeing, including reducing burnout and protecting against traumatic stress symptoms.

Qualitative themes

Attendees were asked for examples of their experiences attending the service. The main themes were a sense of connectedness, safety, self-efficacy and hope. Illustrative quotes for each of these themes are shown in Table 1. The quotes clearly outline how useful the service was for those who attended. The findings reflect the trauma informed care model, which indicate the effectiveness of this service in helping maternity colleagues to feel psychologically cared for and safe in the work environment.

| Connectedness | Psychological safety | Self-efficacy and hope | Independent person to speak with |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘A hugely valuable and empowering experience which brought together multidisciplinary colleagues to share and heal together’ | ‘I was nervous at first but [the clinical psychologist] made the environment calm and safe. I felt able to discuss my feelings and talk through the issues I was having’ | ‘The service makes you feel valued as an individual - having this service available to suppor staff makes them feel just that - supported and valued, and I think will help with staff wellbeing and retention’ | ‘Being able to talk to someone independent of the case, who was able to visualise my role in it meant I was able to see things more clearly’ |

| ‘It was nice to be part of a discussion with other colleagues who are going through the same difficulties at work. I had never done anything like this before so I did not know what to expect’ | ‘I felt very calm in [the clinical psychologist's] presence, I felt listened to and understood, and was provided with some good techniques/tools to use for reflecting/debriefing’ | ‘I felt heard and validation for the way I was feeling. I felt supported’ | ‘It was very helpful to be able to discuss my personal emotional feeling with a trustworthy person who is a professional and also outside of circle of friends, family and colleagues’ |

| ‘I can feel the benefit within the team and we have a better understanding of each other and the impact our own experiences have on us individually’ | ‘It was a great opportunity for me to share and talk about a difficult case I have at the moment’ | ‘I feel like I enjoy my job more’ | ‘Having someone who is independent of the case available meant new thoughts and advice were shared about how I could manage this going forwards’ |

| ‘Supportive, felt I was part of a team and listened to’ | ‘Emotional but well-handled and supportive’ | ‘I have found it really helpful to have an expert to help me put support mechanisms in place to safeguard my mental health’ | |

| ‘I feel a greater sense of cohesion and compassion and bond within my team after attending the debrief’ | ‘100% helpful. Safe place to talk and not be judged’ | ‘I think everyone should be able to use this service and needs t be more hours allocated’ |

Discussion

The NHS England (2023) 3-year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services specifically states that more needs to be done to improve the experience of staff in order to retain them. Maternity colleagues that are burnt out and experiencing work-related stress and emotional wellbeing difficulties, such as traumatic stress symptoms, are likely to take time off for illness and not feel valued and supported by the workplace, leading to higher rates of staff turnover and difficulties with retention. A lack of clinical governance over psychological interventions delivered by maternity staff also poses significant risks of patient harm and potential litigation costs. As such, supporting the maternity workforce in protecting their wellbeing and creating a culture of compassion and empowerment for staff is a key protective factor.

This study explored outcomes for midwifery colleagues following their participation in a novel clinical supervision service. The results highlight the effectiveness of this service, including improvement in overall emotional wellbeing for midwives who took part. The data also illustrate a reduction in burnout and traumatic stress symptoms, as well as improved job satisfaction. These outcomes, along with the qualitative feedback, demonstrate the positive impact of this pilot service.

Given the high levels of distress, trauma and burnout experienced by midwives and wider maternity colleagues (Leinweber and Rowe, 2010; Rice and Warland, 2013; Sheen et al, 2015; Leinweber et al, 2017; RCM, 2023), advocating for system level change across maternity services is key for the profession. This pilot demonstrated the direct benefits to staff of having trained psychological professionals in maternity services who can offer clinical supervision and models of staff support. These findings are in line with those of Sheen et al (2015; 2016) and Slade et al (2018), who also found reductions in traumatic stress symptoms and burnout for midwives who attended psychological interventions provided by trained psychological professionals. Previous studies have highlighted the risk of emotional wellbeing difficulties in midwives having implications for delivery of safe, high-quality patient care (Hunter et al, 2019). Embedded clinical psychology provision has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on self-reported emotional wellbeing and workplace-related trauma, including burnout and compassion fatigue. Therefore, it is anticipated that this will positively impact delivery of safe, high-quality care.

The findings from this study reflect recommendations from the Ockenden (2022) report and research by Hodkinson et al (2022) regarding the importance of maternity colleagues having access to staff support. This would help to ensure that women, birthing people and families using maternity services have the best chance to receive high-quality psychological and trauma-informed care from midwives.

A similar model could be advocated for across the wider maternity system, with such provision playing a vital role in protecting the mental health and welfare of colleagues. It would also offer protection for clinical governance for specialist midwives without formal psychological qualifications who use psychological principles to inform their work with patients. In view of the findings and previous research, this pilot service appears to have played a vital role in advocating for the importance of maternity services embedding clinical psychology provision into their service.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to the pilot service. The remit of the clinical supervision was limited to specific groups of midwives and the pilot did not include support for wider colleagues across maternity (with the exception of the debriefs), including doctors. There was limited time to provide the service, and the clinical psychologists' contracts were fixed-term, meaning there was insecurity from the start regarding the future of the service. In a busy service, allowing time for colleagues to attend sessions was the biggest barrier, especially for debriefs, with clinical need understandably taking priority. There was also a significant administrative demand on the clinicians providing the service (liaising with staff, booking room spaces, sending reminders of sessions) that had not been accounted for in the planning. Additionally, it is important to note the limited sample size (n=10) for follow-up data.

While the pilot clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of access to clinical psychology provision for midwives, it was not possible to evidence any impact on staff retention. It had been hoped that retention rate and the impact for those who accessed the service could be compared with colleagues who were not offered the service. Unfortunately, it was not possible to access these data. This was also the case for sickness data, meaning it was not possible to assess the service's impact on staff sickness rates.

Implications for practice

The data strongly indicate the effectiveness of this service and protectiveness for midwives in terms of emotional wellbeing and improved job satisfaction. Therefore, it is recommended that clinical supervision and staff support models are provided by clinical psychologists in maternity services.

This novel clinical supervision service met recommendations for maternity staff support highlighted in the Ockenden (2022) report. Well-supported staff are more present, productive and able to be compassionate, which has a direct impact on the quality of care that women, birthing people, babies and families receive. It is recommended that this service continue as a protective mechanism for patients as well as staff. Given the national litigation costs for maternity services and high burnout rates of doctors, it is recommended that the service remit is widened to include doctors.

Conclusions

The service provided in this pilot enabled colleagues to feel psychologically safe, valued, empowered and supported, shown in the significant improvement in emotional wellbeing and reduction in burnout and traumatic stress symptoms. Such outcomes have the potential to help staff to thrive, which can improve the experience of care and outcomes for women, birthing people and their babies. This pilot study demonstrated the value of clinical supervision provision and models of staff support provided by senior clinical psychologists in maternity services. The need for such services nationally could lead to significant improved outcomes to protect the maternity workforce, as well as improve patient care.