Historically, childbearing women were generally young and healthy, yet societal changes and fertility treatments have meant women who are older or with pre-existing conditions becoming pregnant have an increased risk of adverse outcomes (Geraghty et al, 2019). Coupled with this, there is a justified but increasing, focus on achieving a fulfilling birth experience, retaining choice and control; perceived to be prioritised over medical professionals' opinions of maternal and neonatal well-being (Buckley, 2009). Consequently, some women decline routine maternity care, including choosing home birth against medical guidance.

The ‘National maternity review’ (NHS, 2016) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ([NICE], 2017) recommend that women have choice of birth setting. Feeley and Thomson (2016) suggest that not all women are provided with information regarding home birth, as overstretched and at times inflexible maternity services appear to oppose unconventional choices. This is at odds with the Nursing and Midwifery Council's ([NMC], 2018) guidance and UK law (Human Rights Act, 1998) which advocate respect for autonomy and choice.

Reluctant maternity services may force women to seek alternative support to achieve their choices, such as friends, family and lay workers including doulas. However, UK law (Nursing and Midwifery Order, 2001) excludes anyone other than registered midwives or medical practitioners attending women in childbirth (excluding emergency situations), thus leaving unregulated birth supporters vulnerable and open to prosecution.

Since the removal of ‘superviser of midwives’ (SoM) in 2017, anecdotal evidence suggests community midwives feel a sense of isolation and lack of support during complex situations such as home birth against advice. SoMs provided a 24-hour service, giving midwives an identified contact for immediate support and advice (Rouse, 2019). Instead, professional midwifery advocates (PMA) now support midwives professionally and emotionally; evidence, however, suggests that the availability of training for the role is sparse (Sonmezer, 2017), substantive duties override PMA responsibilities and shift working, and senior status of PMA's prevents or limits midwives' ability to access this support (Rouse, 2019).

Literature discusses women's reasons for unconventional birth choices (Keedle et al, 2015; Holten and de Miranda, 2016; Hollander et al, 2017), however, no evidence was found exploring the experiences of community based midwives who attend these births, thus the focus of this research.

Research question

What are midwives' experiences of supporting women who choose to birth outside of guidelines?

Research aims

To explore the lived experiences of midwives who have looked after women at home birth against trust guidance in a single NHS Trust.

Methods

Design

A hermeneutic interpretive phenomenological design was adopted (Crist and Tanner, 2003).

Participants

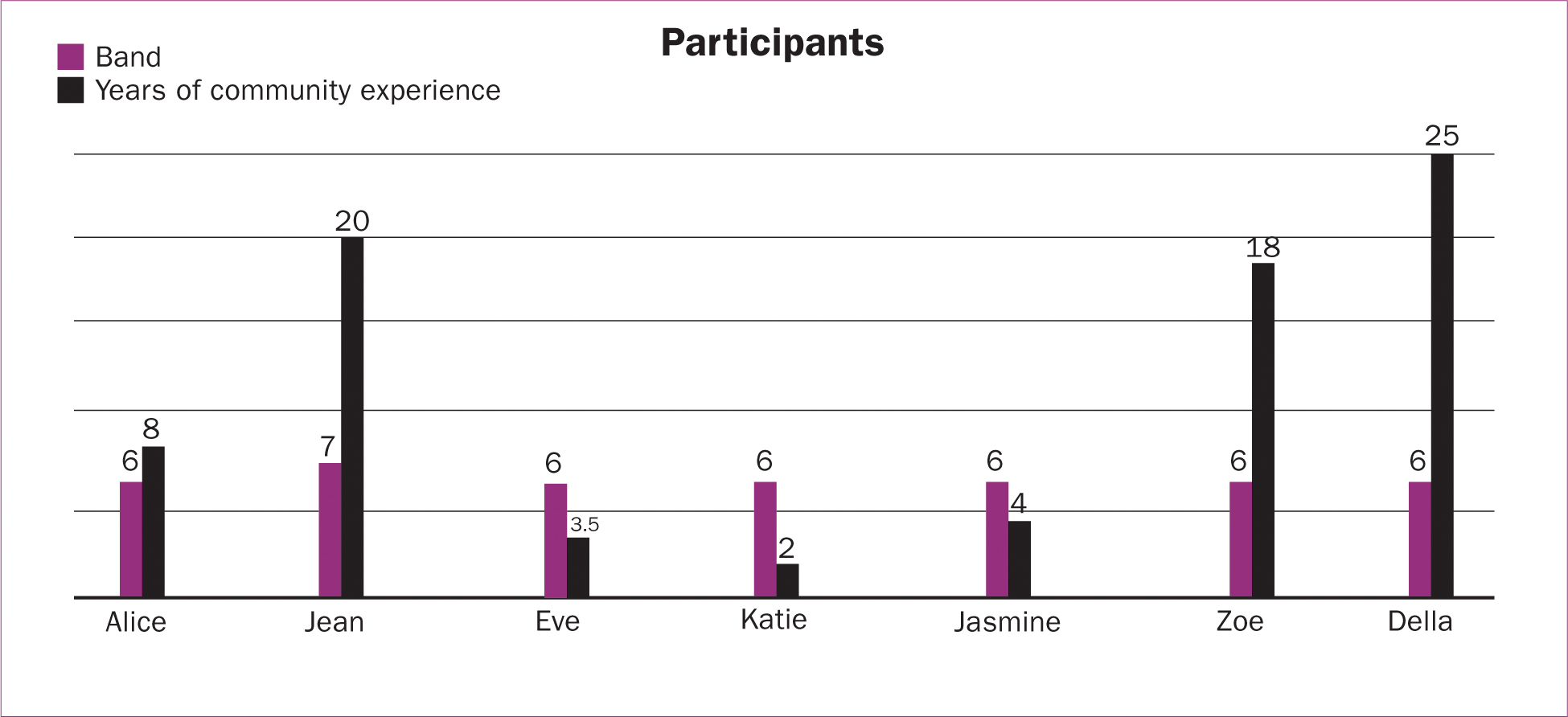

Purposive sampling identified seven community midwives employed by a single NHS Trust who had attended home birth against advice. The Trust's community maternity services were divided into four community teams (not providing intrapartum care) and one continuity team. All (excluding the continuity team because it was new) were represented in this study. The home birth service was staffed by all community midwives via a single on-call rota. Participants had varying levels of experience in a community setting and were deemed representative of the community service as a whole.

Data collection

Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted by the researcher (a community midwife at the Trust) with an opening question and follow-up prompts (Table 1). The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and pseudonyms allocated to protect confidentiality (NMC, 2018). Member checking was offered but no transcripts returned.

| Can you tell me about your own experience of supporting women who choose to birth at home outside of guidelines? |

|---|

| Why was it outside of guidelines? |

| What was your overriding memory? |

| Did this experience change in your practice in any way? |

| Do you feel that you have gained anything from this experience? |

| Is there anything else you would like to add? |

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using a hermeneutic cycle (Crist and Tanner, 2003), searching data for significant points and highlighting data by allocating different colours to different categories. Some data covered more than one category and was therefore highlighted in both. Transcripts were then compared to interpret shared experiences. Insider knowledge and research supervisor review was utilised to ground the data prior to further analysis, resulting in a number of sub-themes and drawing together experiences (choice, unknown midwife, confidence, safety and support). These sub-themes were further expanded to reflect nuances (nine sub-themes) and then condensed into three main themes (Table 2).

| Main themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Supporting women's choice |

|

| Perceived levels of risk |

|

| Support for midwives |

|

Findings

Supporting women's choice

The factors impacting support for women's choice and the implications of this on midwives were an important aspect for all participants and their experiences were grouped together in the context of how this effected women's informed choice. All participants agreed informed choice was fundamental to women-centred care, even if local guidelines were contravened:

‘Every woman has the right to make her own choices as long as they are informed.’

Some participants reflected on the validity and source of the information provided, one reporting midwives delivering information to coerce women's decisions:

‘… you can give women information in a positive or a not so positive way depending on if you want to sway their opinion.’

Reflecting on the historic place of SoMs in facilitating maternal informed consent and supporting midwives, Alice suggested:

‘Supervisors would go out and have those conversations with the women wanting to be at home outside of guidance, whereas now that conversation falls to us.’

Instead, in the local context, these conversations are now held in a birth choice clinic, where a birth plan is developed, facilitated by a consultant midwife. Della, however, identified a downside to this as a lack of consideration or input from the midwives who attend such home births when developing plans:

‘I feel that there is a service there that has replaced supervision … but the people making those decisions are not actually the ones who are present at these deliveries.’

Compounding this, local service provision did not accommodate continuity of carer for home birth, therefore the participants were often unaware of the woman's preferences and choices on arrival:

‘She's not one of my ladies which is kinda typical of a home birth. They tend to be other people's women and you don't know much about them.’

In regard to barriers, birth supporters in the home environment were deemed to sometimes present an additional challenge in ensuring informed choice:

‘Where we have a barrier between us and the woman, it becomes really difficult. Has she actually had that information … and has she fully understood?’

Similarly, Katie and Jean reported experiences where doulas, or partners, prevented them from conversing with women, resulting in difficult situations.

In summary, participants acknowledged the importance of informed choice for women but felt that changes in service provision, particularly the loss of supervision, had impacted on the facilitation of choice. Furthermore, some reported that external factors, such as birth companions, presented a barrier to facilitation of informed choice.

Perceived levels of risk

Participants' perceptions of risk influenced the way they viewed the facilitation of home birth against guidelines. Previous experiences and confidence impacted participants approach to potentially going outside of guidelines:

‘I think that your confidence in a situation is affected by your experience. If you've experienced that before, it might make you more confident because you dealt with it well last time, or it might influence you negatively because it didn't go so well … You are always competent but confidence really depends on your experience.’

The midwives reported that they were often attending unknown situations when facilitating home birth and this affected confidence:

‘We always feel a bit vulnerable, don't we? I mean we are going to strangers' houses in the middle of the night; we don't really know what to expect.’

In contrast, care plans formulated between women and midwives in advance, identifying risk factors and birthing environments were welcomed in alleviating anxiety. Participants unsurprisingly aimed to achieve positive maternal and fetal outcomes, and recognised that women may not perceive risks in the same way. They expressed this particularly in relation to women declining observations:

‘We really didn't know what was going on; we had nothing to go on, we didn't know if the woman was deteriorating. She could've been turning septic.’

The wider impact of this for midwives, professionally and personally, was recognised:

‘I think it's important to remember that when things do go wrong at a home birth, it affects an awful lot of people and very definitely the midwives that are looking after that lady, their peers, their colleagues, their families, everyone.’

Two participants felt it was important that women are fully informed, not only regarding risks, but also relating to the wider impacts of their choices. Regardless of this, most of the participants felt they had no option to decline care, although no participants mentioned risk of litigation interestingly:

‘I don't know where I stand if I can decline attending. I don't believe that you can because of the code of conduct and stuff. I think if something went wrong that could end my career.’

Overall, participants all reported situations where they had not felt comfortable or confident and were placed in ‘risky’ situations but felt unable to decline providing care.

Support for midwives

The level and nature of support provided to midwives, professionally, personally and in terms of Trust guidance when facilitating home birth outside of guidance was a common factor discussed. Every participant, for example, advised that they had called the second midwife immediately for support and an alternative viewpoint on the situation, despite this not always being ‘clinically’ required.

Participants considered that guidelines for the local birthing unit were too rigid, forcing women to opt for home birth to achieve their birth choice, thus increasing the risk of adverse events in a remote location:

‘She would have gone in if she felt that she could've had a water birth on a low-risk unit which obviously would have been a safer place for her. I think some of them feel maybe backed into a corner to stay at home.’

Many participants expressed feeling isolated and alone in such situations:

‘I felt vulnerable on my own. The unit midwives have loads of people there to help if things go wrong; it's not the same when the doctors aren't there.’

In addition to immediate support from a community midwife at home, mixed viewpoints were presented regarding additional support available from the obstetric-unit:

‘Who would we speak to? I mean, it was night, the senior midwife has probably never been to a home birth in her life. They would probably just tell us to transfer in and that's not gonna go down well is it?’

Conversely, the senior midwife or manager on call were recognised by some participants as being a valuable source of advice:

‘If it was at night and I felt unsafe, then I would call in to the senior midwife and discuss it with them.’

Further, Alice reported a lack of empathy from senior staff on occasion when support was needed following traumatic events, highlighting a competitive attitude and an expectation for staff to continue practicing regardless:

‘“Why is she stressing? I've coped with far worse than that!” Then it makes that poor midwife be afraid to ask for help.’

Participants identified the downsides to SoMs being replaced by a PMA service in availability of support available now:

‘They don't work every day, there's only three of them and they are all band seven so they are usually busy and don't have the time to support us.’

With regard to personal support, none of the participants identified a debriefing service in the local Trust. Instead, participants naturally incorporated reflection into their practice as a debriefing tool.

Similarly, peer support was identified by all participants as the most valued and trustworthy source of support:

‘I have friends who are midwives that I can talk to as well … I've always found that very helpful.’

While all participants suggested there was a level of support available to them when providing care outside of guidelines, many questioned its efficacy, instead utilising their own peer networks and personal reflection mechanisms to cope with the challenges, and noting again an adverse impact of the disbanding of SoMs. Additionally, it was considered that the restrictions imposed by trust low-risk care guidelines, had the adverse effect of potentially increasing risk.

Discussion

Supporting women's choice

The midwives in this study unanimously agreed that women's choice should be upheld, including where this contravenes guidelines, supporting NMC (2018) and NICE (2017) guidance. Midwives suggested however, that the assumption that women are making an informed choice is questionable. Existing research also questions this, suggesting instead that many women seek non-professional sources of information (Hinton et al, 2018). Additionally, institutional factors such as excessive workloads, an overly medicalised approach and a risk-averse culture can prevent healthcare professionals from explaining in depth (Kruger and McCann, 2018) or providing non-biased information (Healey et al, 2016; Brady et al, 2019).

Nonetheless, in terms of care provision, Magill-Cuerden (2012) suggest that if women request care against medical advice, a manager and the midwife should discuss the care plan with women, as happened in the birth choice clinic in this study. However, this was recognised as having limitations, such as women needing to travel to access it, a potential lack of experience in home birth of the midwife running it and it not being facilitated by the midwives providing the care.

When providing home birth care against guidelines, most participants relayed situations where barriers to communication existed, including when doulas had been employed. Evidence demonstrates that partners and doulas can act as advocates for women and safeguard against mistreatment (Bohren et al, 2017). However, like others, this study revealed that when communication was poor, barriers were present and midwives felt fearful and vulnerable (Toohill et al, 2019). It is important to research the underpinning reasons for women's preference for non-midwifery support because unlike midwifery, there is a lack of regulation and consistency in doula provision (McLeish and Redshaw, 2018).

Participants recognised that local provision often resulted in unfamiliar midwives attending home births and consequently not knowing the full situation or what choices had been made. Dedicated home birth teams in other areas, such as in Tower Hamlets and Birmingham, have successfully addressed this by caseloading small cohorts of women, facilitating regular obstetric emergency training sessions, working with the local communities and ensuring a ‘known midwife’ attends the birth (Cross-Sudworth et al, 2018; Foley et al, 2019). Maternity services across the country are similarly re-structuring to comply with the ‘Better births maternity review’ (NHS, 2016) and to provide continuity of carer for every woman. As such, this may be an ideal opportunity to alleviate this (Dahleberg and Aune, 2013). However, studies, including those above, suggest that while this approach has merit, there is also negativity around continuity models amongst midwives due to risk of burnout and staff shortages (Young, et al, 2015; Taylor et al, 2019).

Perceived risk

All participants concurred that the level of risk impacted on their confidence to support women outside of guidelines. The assessment of risk is however relative; certain risks are deemed acceptable and midwives' and women's priorities may not align (Healey et al, 2016). In general, women themselves determine how at-risk they feel and believe that their choice is safe (Borelli et al, 2017). However, differing perceptions of risk may impact women's engagement with professionals (Lee et al, 2016a). Buckley (2009) concurs with this, stating satisfaction with the birthing experience is attributed more to a woman's involvement in decision-making than outcomes. Participants expressed concern however, for the implications on maternal and fetal safety, caregivers and others when women decline routine care.

Some participants also felt unable to decline attending situations where their confidence or experience was lacking, fearing being considered incompetent, potentially increasing work-induced stress (Bedwell et al, 2015). This is crucial because evidence suggests stress can be draining for midwives, increasing risks of burnout and a poor work/life balance, and ultimately contributing to midwifery attrition rates (Young et al, 2015).

Bedwell et al (2015) report that midwives experience vulnerability when confidence is low yet interestingly, participants in the study described an element of anxiety and vulnerability when travelling to any home birth due to the unknown. In line with this, it is suggested that prior knowledge of risks, or positive experiences of particular situations can increase midwives' confidence in facilitating birth (Dahlen and Caplice, 2014) which is what participants in this study suggested.

Trust guidance around midwife-led unit (MLU) care was deemed on occasion to exacerbate risk in this study, forcing women to choose birth at home, negating the chance of constructive conversations between women and the wider team to address concerns and support choice. Similarly, a study by Lee et al (2016) found that women were seeking communication that was respectful of their thoughts and feelings, and in the absence of this, followed their own instincts rather than professional advice.

Support for midwives

All participants highlighted that additional support was needed when supporting women to birth at home outside of guidance and, without exception, participants undertook self-reflection and sought support from peers. Sheen et al (2016) support this, suggesting that midwives often accessed emotional and social support from colleagues, and this is deemed to increase self-confidence and positive emotional well-being (Bedwell et al, 2015).

Concurring with previous findings, remote support while at a home birth was deemed to be problematic in this study; Madeley et al (2019) noted a similar disparity in approach and an oppositional relationship between midwives practicing in different models which impacted upon support given. This study further noted that the timelines of support was also lacking, due to the fact that those providing the support were doing so while also running busy labour wards.

Every participant discussed SoMs, with most recognising the benefits of empowering women and ensuring midwives retained confidence and competence in line with previous research (Carr, 2008)-this service is now replaced by PMAs (Rouse, 2019). The participants in this study considered PMAs clinically confident, competent and approachable yet, as suggested, they had many other responsibilities in their substantive roles and thus lacked time. Rouse (2019) concurs, recognising limitations on the ability to provide protected time. This is concerning considering that restorative clinical supervision (provided by the PMA role) can improve resilience levels, limit stress and burnout, and enhance the ability of staff to make appropriate judgements in difficult situations (Rouse, 2019).

Conclusions

This study is the first to present community midwives' experiences of caring for women at home birth outside of guidelines but highlights the need for further research in this area on a wider scale. The study found that midwives caring for women outside of guidelines felt that their right to autonomous decision-making should be upheld, regardless of guidance. They did, however, recognise many barriers and concerns around the facilitation of this, both for women and their own practice. Most participants experienced the choice to have non-midwifery support for birth against guidelines, as a challenge to informed consent. Many of the experiences recounted involved doula support, identifying the need for further research regarding why women chose lay support over professional care for unconventional birth.

Perceptions of risk were both influenced by and had an impact on the participants' experiences, confidence and concerns around safety. Participants similarly perceived risk relating to women's understanding of the impact when declining routine midwifery care, compounded by rigid MLU guidelines, forcing women to birth at home to achieve choice. The recommendation being that MLU guidelines are reviewed, alongside widening voice forums for women and other supporters to improve working relationships and better facilitate choice.

It is likely that in the local context, the provision of a dedicated homebirth team, under the continuity of carer (‘Better births’) models would assist with building relationships and supporting choice. However, this may be limited by the impact of staff shortage and burnout reported in previous studies and therefore will need to be constantly revisited. Clinical support was crucial; a second pair of hands and an alternate viewpoint. The credibility and validity of support when the advisor may have never attended a home birth or was busy working clinically was questioned. The PMA role has been developed to support midwives yet limited numbers and lack of availability have left community midwives feeling vulnerable and unsupported and the impact of this needs further insight. Thus it is crucial that protected time is embedded into the development of this role.

Limitations

The study was only undertaken in a single NHS Trust so may not represent the experiences of the wider population. In addition, the sample was self-selecting which may not accurately represent experiences due to the sensitivity of the topic. Furthermore, while every attempt to mitigate bias/ethical risk was taken, such as the use of a gatekeeper for recruitment, the offer of member checking and supervisor review of analysis, the main researcher, was a midwife at the Trust.