The ability to safely and effectively vaccinate in pregnancy offers important protection to both pregnant women and their babies in utero and from birth against potentially serious infectious diseases. In developed countries, however, there is a perceived reluctance for pregnant women to take up immunisation as a preventive intervention. This is not surprising given the general advice that some medicines in pregnancy can be harmful (www.nhs.uk/Conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/Pages/medicines-in-pregnancy.aspx). Thus confident and knowledgeable professionals, who are able to provide information and immunisations to these women, are key to the success of such programmes.

Pertussis

Pertussis (whooping cough) immunisation for all pregnant women was recommended as an outbreak control measure in England from October 2012 following the declaration by Public Health England (PHE, previously the Health Protection Agency) of a pertussis outbreak earlier that year (Chief Medical Officer, 2012). In 2012, the highest recorded pertussis incidence for over 15 years was seen with 14 deaths in babies too young to be protected by infant vaccination (PHE, 2013a). The pregnancy programme has been extended until at least 2019 on the advice of the national independent expert advisory committee, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) (PHE and Department of Health (DH), 2014). In the current UK programme, the pertussis vaccine is ideally offered between weeks 28 and 32 of pregnancy; and may be offered up to 38 weeks gestation. Pertussis immunisation is recommended routinely for all pregnant women in a number of countries including the USA, New Zealand, Belgium, several South American countries and Australia. However, national vaccine coverage has not been published in these countries.

Surveillance of the pregnancy programme in England has generated good data to support the effectiveness and the safety of this immunisation strategy. Two studies using different methods have each shown that babies born to mothers vaccinated at least 7 days before birth had a reduced risk of pertussis disease, of more than 90%, in their first few weeks of life when compared with babies whose mothers had not been vaccinated (Amirthalingam et al, 2014; Dabrera et al, 2014). While higher levels of antibodies had been demonstrated previously in babies whose mothers received pertussis vaccine in pregnancy compared to those whose mothers had not received the vaccine, this was the first time that protection against the disease in infants had been shown. Vaccine safety in pregnancy has also been demonstrated in a large UK study of nearly 18 000 vaccinated women undertaken by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Importantly, it found no safety concerns relating to pertussis vaccination in pregnancy with similar rates of normal, healthy births in vaccinated and unvaccinated women (Donegan et al, 2014).

Influenza

Influenza infection in pregnancy is associated with increased risk of severe disease, hospitalisation and death when compared to non-pregnant women, and this risk is worsened in pregnant women with underlying risk factors (World Health Organization (WHO), 2012). This can result in poor pregnancy outcomes with complications including: stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm delivery and low birth weight. In addition, infants under 6 months have the highest rate of hospitalisations and GP consultations for influenza in the UK. The MBRRACE-UK report identified 36 maternal deaths from influenza between 2009 and 2012 accounting for 1 in 11 maternal deaths over that period. The report highlighted the importance of vaccination against influenza in pregnancy in the UK and of working to maximise uptake to ensure prevention of future influenza-related maternal deaths (Knight et al, 2014). The data supporting maternal pertussis immunisation add to the existing evidence that influenza vaccination in pregnancy offers benefits in three ways (WHO, 2012):

There is evidence that influenza vaccination is safe at any stage of pregnancy with no evidence of increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome in vaccinated women (Tamma et al, 2009; Keller-Stanislawski et al, 2014; Regan et al, 2015). On this basis, the WHO (2012) recommends that pregnant women should have the highest priority for seasonal influenza vaccination programmes. Many countries, e.g. most EU member states including the UK, Australia, New Zealand and the US, recommend influenza vaccination for pregnant women at any stage of pregnancy. National uptake data are not available from the majority of countries, but within Europe, where reported, UK countries had markedly higher uptake. Influenza uptake for pregnant women for the 2012–13 season was reported by only six EU member states outside the UK: these all reported coverage of around 23% or lower with four countries reporting coverage of <5% (European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control, 2015). National uptake of flu vaccine in other countries is limited although the US has estimated 52.2% uptake of flu vaccine in women before or during pregnancy based on a sample of 1619 respondents in the 2013-14 influenza season (Ding et al, 2014).

PHE undertook a UK survey of pregnant women and women with young children to explore their attitudes to immunisation in pregnancy in general, and specifically, to protect young babies against pertussis. Wiley et al (2013a) studied women's and health care professionals' attitudes to influenza vaccination in pregnancy, and Kennedy et al (2012) and Wiley et al (2013b) have respectively undertaken US and Australian studies of attitudes to influenza and pertussis immunisation in pregnancy among post-partum women.

Methods

Pregnant women and mothers of children under 2 years of age were identified through the Bounty Word of Mum™ Research Panel. The parenting club Bounty® is an organization that is estimated to access approximately 96% of primigravida women in the UK. This Research Panel comprised 27 000 women, who agreed to participate in surveys run by Bounty and the list is updated regularly. The survey link was emailed to panellists between the 14–21 January 2013 with pre-specified quotas on participants' stage of pregnancy and age of child. Initially, women in the first trimester were targeted, as the most difficult group to access, with the survey not open to other participants at this point. All women who participated and completed the questionnaire were entered into a prize draw for shopping vouchers in line with usual practice for the Bounty Word of Mum™ surveys. The questionnaire was anonymously completed but responses could be individually linked to previously collected sociodemographic data.

The questionnaire consisted of 60 questions on 6 different topics, including 10 structured questions on vaccines in pregnancy, in a web-based questionnaire built by Easyinsites. The email invite included a brief description of the topics covered in the survey. The immunisation in pregnancy questions were developed from quantitative vaccination survey questions selected from the DH tracking survey of parental attitudes towards vaccines and vaccine programmes that ran between 1991 and 2010 (DH, 2015). As this was undertaken as part of a national outbreak response, ethical approval was not required and data collation was covered by existing Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations (2002) information governance approvals.

The data obtained were only available to PHE in an aggregated format and significant differences between groups were tested using the Chi-square test.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

Email invitations to participate in the survey were sent to 25 000 women in the UK. All 1892 (8%) respondents who completed the online survey were female; the characteristics of these women are summarised in Table 1. Population statistics for England and Wales (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2012) reported that 73% of women aged 20-44 years defined themselves as white British and 9% as white non-British, 2% classified themselves in mixed/multiple ethnic groups, 10% as Asian/Asian British and 4% as Black/African/Caribbean/Black British. Equivalent data are not available for the UK but these population statistics suggest that Asian and Black British women may be under-represented and the white British over-represented in our study. In the survey there was an oversampling among those in the most affluent social groups, and an undersampling among those from the least affluent groups, when compared to the general UK population (National Readership Survey, 2014) (Figure 1).

| Characteristics | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | <25 years | 212 | 11.2 |

| 24–34 years | 1212 | 64.1 | |

| >34 years | 468 | 24.7 | |

| Pregnancy/age of child | Pregnant | 587 | 31.0 |

| Child <1 year | 898 | 47.5 | |

| Child 1–<2 years | 407 | 21.5 | |

| Parity | First time mother | 1209 | 63.9 |

| Have other children | 683 | 36.1 | |

| Ethnicity | White British | 1502 | 79.4 |

| White non-British | 198 | 10.5 | |

| Indian | 37 | 2.0 | |

| African | 28 | 1.5 | |

| Pakistani | 27 | 1.4 | |

| Afro-Caribbean | 18 | 1.0 | |

| Middle Eastern | 6 | 0.3 | |

| Bangladeshi | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Other | 73 | 3.9 | |

| Living arrangement | Living with partner full time | 1745 | 92.2 |

| With partner—not living together full time | 73 | 3.9 | |

| Currently single | 67 | 3.5 | |

| Other | 7 | 0.4 | |

| Working status | Full time working mother | 396 | 20.9 |

| Part time working mother | 354 | 18.7 | |

| Stay at home mother | 480 | 25.4 | |

| On maternity leave | 612 | 32.3 | |

| Other | 50 | 2.6 | |

Acceptance of vaccination in pregnancy

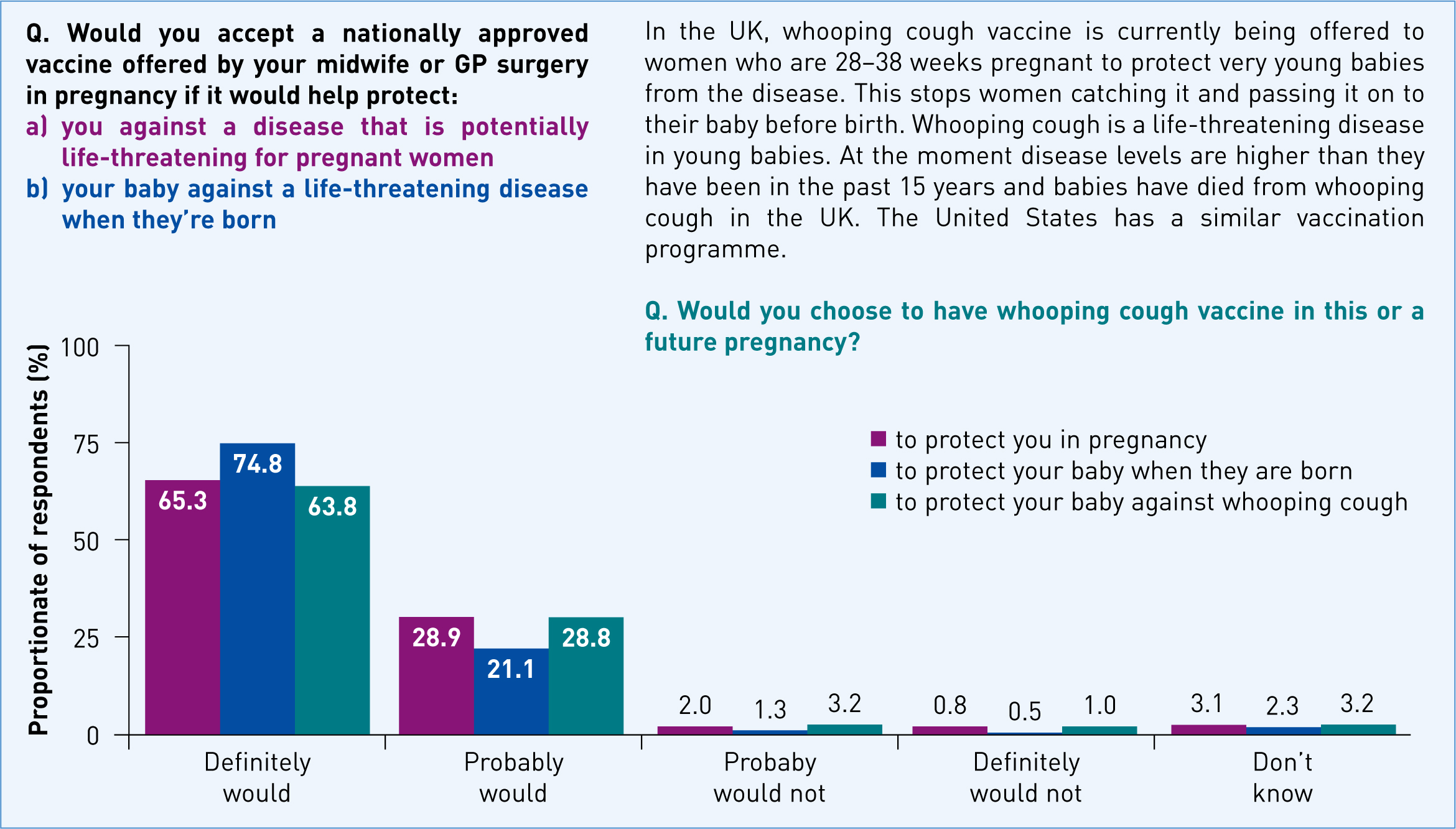

Most respondents indicated that they would accept a nationally approved vaccine offered by their midwife or GP surgery during pregnancy to protect either themselves (65.3%; n=1235) definitely and 29% (n=547) probably would) or their baby when it was born (74.8%; n=1415) definitely and 21.1% (n=399) probably would) (Figure 2). Significantly more women who were pregnant or had a child aged 6 months or younger at the time of the survey (n=1073; 56.7%) said that they would definitely accept such a vaccine for themselves (68.3%; n=733) or to protect their child (77.3%; n=829) than women with older children (n=819), of whom 61.3% (n=502) would definitely accept a vaccine for themselves (P<0.01) and 71.6% (n=586) to protect their child (P<0.01). Less than 1% of mothers said that they would definitely not be immunised to protect themselves (0.8%) or their baby (0.5%).

A separate question provided a small amount of background information on the pertussis immunisation programme in pregnancy and then asked all respondents whether they would accept this vaccine in their current or in a future pregnancy. Most women indicated they would be vaccinated (63.8% (n=1208) definitely and 28.8% (n=544) probably would). Seventy-one percent (n=766) of women who were pregnant or had a child aged 6 months or younger said that they would definitely accept a pertussis vaccine in pregnancy; significantly more than the 54.0% (n=442) of women with older children who said they would definitely accept (P<0.01). In total, less than 1% of women said that they definitely would not accept pertussis vaccination in pregnancy.

Uptake of pertussis vaccine in pregnancy

The pertussis vaccination in pregnancy programme had only been in place for 3 months when the survey was undertaken and thus only women in the latter stages of pregnancy or with babies under 3 months should have been offered the vaccine. Of the 33.7% (n=638) of respondents offered the vaccine 74.9% (n=479) had been vaccinated. However, 20.5% (n=98) of the women who said they had been vaccinated were either too early in their pregnancy or had a child who was too old for this to be true. Of the 638 women who said they had been offered pertussis vaccine in pregnancy, 69.7% (n=445) felt they had all the information they needed to make a decision, 21.3% (n=136) felt they had some information but would have liked more. Overall, 8.9% (n=57) either had no information or not enough to make a decision.

Nine percent (n=58) of the eligible women who had been offered a pertussis vaccine were not vaccinated and provided a reason for this. For most of these 58 women, practical issues precluded immunisation: 34.4% (n=20) had not yet reached the eligible stage of their pregnancy, of whom 10.3% (n=6) indicated they would receive the vaccine later; and 24.1% (n=14) had given birth before the vaccine was offered. The most common reason for choosing not to be immunised was vaccine safety concerns (20.6%; n=12) with 6 of the 58 women (10.2%) declining because they felt that they were not given enough information about the vaccine. Nine women (15.5%) who refused the vaccine considered that either they or their baby did not need protection against whooping cough or that they could protect their baby through other means. Six women (10.3%) did not want to be immunised in pregnancy and 5.1% (n=3) did not believe in vaccination. These findings suggest that only 18 of 638 women (2.8%) who were offered the vaccine held views that made it unlikely they would ever be immunised in pregnancy.

Factors considered important when contemplating vaccination in pregnancy

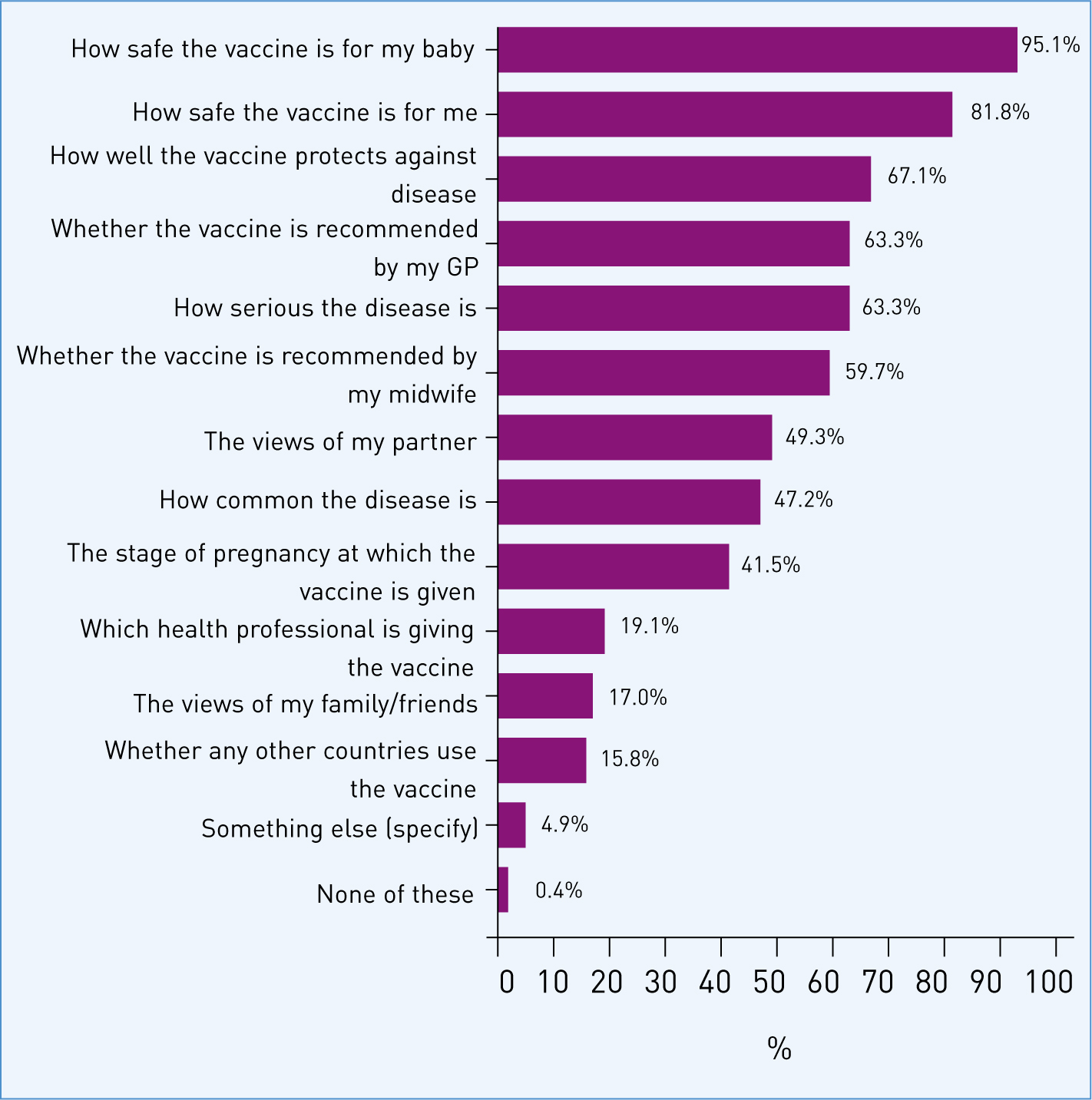

The survey participants indicated that a range of factors were important when making a decision on whether to have a particular vaccine in pregnancy (Figure 3) and safety of the vaccine for the baby (95.1%; n=1799) and for themselves (81.8%; n=1547) were cited as primary concerns. The effectiveness of the vaccine (67.1%; n=1270) and seriousness of the disease (63.3%; n=1197) were also considered to be important factors, together with recommendation by their GP (63.3%; n=1197) or midwife (59.7%; n=1129). For 49.3% (n=933) of women, the views of their partner were also important.

Forty-two percent of women (n=786) indicated that the stage of pregnancy that a vaccine was offered would influence their decision on whether to accept a vaccine. When all women were asked specifically about whether this would affect their acceptance of a vaccine offered in pregnancy in a separate question, half (n=950) said it would not. For 21.7% of women (n=410) their preference was to have the vaccine in the last 3 months of pregnancy and 19.5% (n=369) in the second trimester. A small percentage of women overall (5.2%; n=99) indicated a preference to have the vaccine in the first trimester of pregnancy. Only 1.7% (n=33) of women said that they would not have the vaccine irrespective of when it was offered.

Sources of information about vaccination in pregnancy programmes

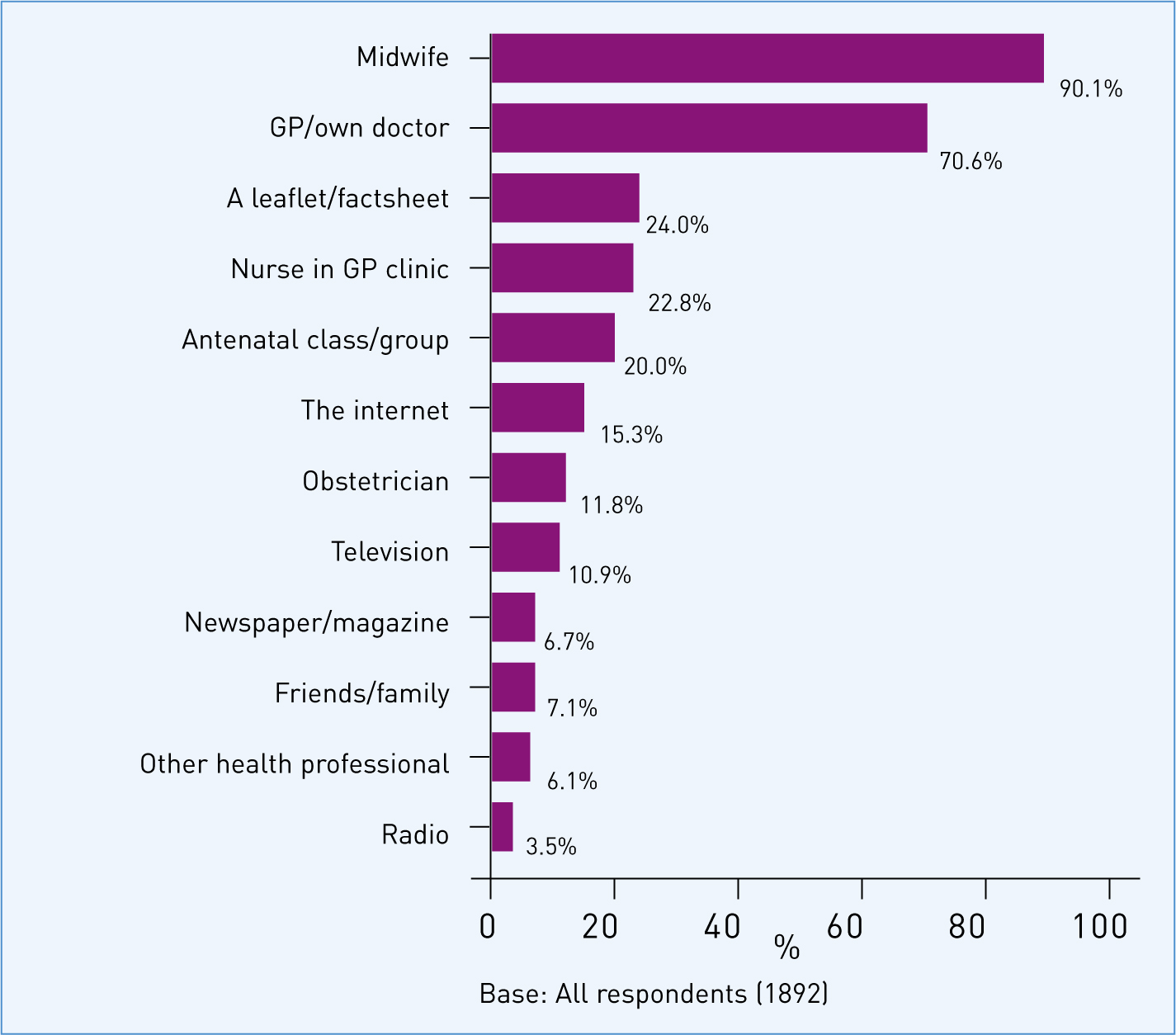

Knowledge of the whooping cough vaccination programme for pregnant women was high among the respondents: 71.1% (n=1345) of all respondents were aware that the vaccine was being offered in pregnancy. The sources that had informed this awareness are summarised in Figure 4.

Women were also asked to identify their preferred source of information about vaccination in pregnancy. As detailed in Figure 5, midwives, followed by GPs, were overwhelmingly identified as the preferred source of information.

Influence of ethnicity

The attitudes of women who classified themselves as White-British differed from women in other ethnic groups. Respondents in the White-British group were more positive towards vaccination than those whose ethnicity was not defined as White-British. For the three questions related to their probability of accepting the offer of a vaccine, White-British women were more likely to answer ‘definitely would’ or ‘probably would’ (P<0.001) accept a vaccine offered in pregnancy, and they were less likely to answer that they definitely would not get any vaccination offered at any stage in pregnancy 1% compared to 4% non white-British (P<0.001).

Discussion

These results indicate a high acceptance of the concept of immunisation in pregnancy. The proportion of women overall who indicated that they would definitely accept vaccination against pertussis in pregnancy to protect their newborn baby (63.8; n=1208), was in line with the DH's published vaccine uptake figures (59.4%) for women who gave birth in January 2013 when the survey was conducted (PHE, 2013b).

This was an opportunity to obtain attitudinal information from a large number of women using a market research strategy. The observed response rate in this study was low when compared to more study-based survey methods where participants are contacted for a subject-specific survey on a single occasion. The January 2013 survey accommodating these ‘vaccine in pregnancy’ questions had a similar response rate to previous Bounty Word of Mum™ surveys, however, and offered a pragmatic approach to obtaining some indication of attitudes in the target population using a market research strategy.

The results indicated that there is broad support for immunisation in pregnancy in the target group and only a small minority of women were strongly against the idea of vaccination in pregnancy. There was a lower percentage of non-White ethnic groups in the population sample than would be expected from the national population profile but the finding that these women were significantly less likely to accept vaccination in pregnancy may indicate a real difference. This perhaps merits a more focused study for non-White women in this population as this survey was not designed to explain these differences. It is important to more clearly identify who these women are and to understand the basis for such reluctance as clear communication, additional support from key health care workers or targeted educational intervention might be helpful. The study identified that 29% of women who were pregnant or who had young children would ‘probably’ accept immunisation against pertussis in pregnancy. It is important to better support such women so that they have access to appropriate, objective, evidence-based information to allow them to make an informed choice and to ensure they are not impeded by a lack of easy access to this service.

Vaccine safety for the baby was identified as a major concern for women. Relevant health professionals must be informed about the outcomes of vaccine safety studies including those completed after a vaccine programme has been established. Well-conducted studies undertaken as part of post-marketing surveillance of vaccination in pregnancy programmes may be particularly useful as they can track exposures in large numbers of pregnant women and compare outcomes, for example the study of nearly 18 000 vaccinated women undertaken by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory (Donegan, 2014) following the introduction of the pertussis vaccination in pregnancy programme in the UK. Most fetal organs are formed by the end of the first trimester; therefore, maternal vaccination after 28 weeks of pregnancy would not be expected to increase the risk of major congenital fetal malformation. This type of additional information could be important for health care workers to further support their confidence in vaccine safety in pregnancy and to enable them to reassure women seeking advice.

Despite the widespread use of tetanus vaccine in pregnancy in resource-poor countries since the 1970s (Blencowe et al, 2010), other vaccination in pregnancy programmes offer a relatively new approach to protect pregnant women and newborn infants against serious disease. While transplacental antibody transfer of pertussis antibody to the infant was established, effectiveness against infant disease had not been proven at the time maternal vaccination was introduced. Participating women indicated that the effectiveness of the vaccine was a key issue for them. Vaccine effectiveness against infant disease following immunisation of the mother in pregnancy has now been shown to be high (Amirthalingam et al, 2014; Dabrera et al, 2014) and, as with the updated information on safety, it is important that the findings of such studies are fed back in a timely way to both health professionals and pregnant women.

Pertussis vaccine uptake in pregnancy in England is encouraging and reached the highest recorded level at 63% in December 2014 (PHE, 2015a). However, as levels of pertussis disease remain elevated in all age groups, other than infants, even this level of coverage leaves a high proportion of young babies vulnerable to infection with an increased risk of serious disease. Similarly, flu vaccination uptake in pregnant women was only 44% in the 2014/15 flu season (PHE, 2015b). For the women being targeted, midwives and GPs play a pivotal role in communicating the importance of the programme. It is recognised that the programme has largely been delivered through general practice across the UK. While this study found that most women do not mind which health professional vaccinates them, participants expressed a strong preference for a midwife or a GP to inform them about the programme. It is therefore important that midwife-led discussions about immunisation in pregnancy during the antenatal period do take place, with sign-posting to the GP for immunisation, or midwife administration of the vaccine where they are commissioned to do so, at the optimal stage of pregnancy with follow-up to see that the woman has received the vaccine.

Posters, leaflets and fact sheets, together with training materials for health professionals, have been developed and produced by all UK Health Departments to support both the influenza and pertussis vaccination programmes. It is important that health professionals are aware of, and have access to, these resources and that they are fully informed of the details of the programmes, including the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, so that they are equipped to recommend vaccination to women seeking information and reassurance. Such recommendation has an affect on immunising behaviour; Beel et al (2013) found a high proportion of women were willing to be immunised during pregnancy if recommended by their healthcare provider. Similarly, Eppes et al (2012) found that increased knowledge in physicians regarding H1N1 influenza, for example, was significantly associated with the frequency of H1N1 vaccination among their patients. Research in Australia suggested that the most important factor for midwives in terms of providing pertussis booster vaccination to mothers was their own perceived ability to provide the vaccination (Robbins et al, 2011). Ishola et al's (2013) study of London midwives found only 26% felt well-prepared for informing women on influenza vaccination in pregnancy. The focus of future research should be on the attitudes of the midwife/GP, their specific training experiences and their confidence in discussing the programme with their patients. Providers of midwifery and GP training should ensure that immunisation is included in the curriculum (Health Protection Agency, 2005).

Conclusions

Immunisation in pregnancy has an important role in preventing diseases with high associated morbidity and mortality in pregnant women, their unborn and newly born infants. In developed countries, immunisation of pregnant women is a relatively recent development. In the UK for example, pregnancy was added as a clinical risk category for routine influenza immunisation as recently as 2010 and pertussis immunisation in pregnancy has been in place since October 2012. Health professionals should be aware that women being targeted for vaccination were not reluctant to be immunised in pregnancy and only 2–3% would definitely or probably not accept the vaccines if offered. For the women being offered the vaccines, safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and perceived seriousness of the disease remain key and good evidence is available to demonstrate both effectiveness and safety for flu and pertussis vaccines. Health professionals are pivotal in informing women, promoting the vaccine and discussing concerns.