Literature has shown that birth place has an important impact on the process of birth (Walsh, 2000), as it influences women's comfort, assurance and control over their bodies (Niles et al, 2023). Gould (2002) argued that a hospital environment fosters a birth procedure defined by a comprehensive medical approach, while Walsh (2000)noted that ‘bed birth’ affected women's mobility. Several factors are known to contribute to a positive birth experience, including an appropriate temperature, floor coverings, comfortable pillows, privacy, control over the presence of a birth companion, the freedom to have food and drink, access to a birthing pool and easy access to a toilet (Walsh, 2000). Nevertheless, the use of these elements in birthing centres worldwide remains infrequent (Niles et al, 2023).

Philosophies of birth

Birth places possess their own paradigm and ideology, and the behaviours of women and healthcare professionals during birth are contingent on their individual philosophy and the specific birthing facility (Dahlen et al, 2021). This has a significant impact on women's agency during birth (Dahlen et al, 2021; Villarmea, 2021). There are several different philosophies that may be applied to the birthing process, including woman-centred and technocratic practices (Dahlen et al, 2021). Technocracy refers to personal and societal interaction with the body that is facilitated by the doctor and the use of technology (Davis-Floyd, 2001). Hospitals typically provide services with a technocratic orientation, while home births or midwife-led practices generally adopt a woman-centered care approach (Davis-Floyd, 2001; Renfrew et al, 2014).

Physiological childbirth can cause discomfort and pain resulting from contractions during labour. A woman-centred approach to labour and birth allows women to establish an environment that is comfortable, to mitigate discomfort. Birth companions and healthcare professionals can serve as a support system to provide continuous assistance to women during contractions (Lothian, 2000). Women have the freedom to move about and consume food and beverages without restrictions (Lothian, 2000; Fathi Najafi et al, 2017).

A medicalised or institutionalised approach to birth is characterised by the provision of medical support following a technocratic paradigm (Davis-Floyd, 2001). This adheres to societal standards and is a self-reflective process influenced by the accessibility and control of risk information, trust-based relationships and the incorporation of pregnancy and birth into the formation of identity; these factors influence decision making (Pintassilgo and Carvalho, 2017). Meanwhile, natural birth typically involves fewer interventions, while acknowledging the need for assistance from healthcare professionals, such as providing pain management techniques and advising on optimal childbirth positions (Borrelli et al, 2018).

The impact of birth experience

A woman's experience of birth can have a significant impact on her paradigm and philosophy. Obstetric violence and overmedicalisation, which are seen as breaching the principles of humanising childbirth, are strongly associated with technocratic birthing (Curtin et al, 2019). Technocratic birth can lead to a negative experience, as this approach views labour as separate from the inherent natural body. A caesarean section represents a technocratic approach to birth, in which the doctor and medical technology actively manage the birth process (Santos and Zhang, 2024). Caesarean birth is associated with a negative experience for women if it does not match their wishes or expectations; women who have an emergency caesarean as a result of complications often intensely feel the negative impact of this traumatic experience (Sarella et al, 2023; Sys et al, 2023; Michael et al, 2024). Negative feelings may also stem from being unable to breastfeed because of the discomfort caused by sutures (Sys et al, 2023). Conversely, the humanistic approach has been shown to lead to positive birth experiences (Davis-Floyd, 2001; Fathi Najafi et al, 2017; Pintassilgo and Carvalho, 2017).

Indonesian context

This study was based in Indonesia, where the health service uses a tiered referral system. Each level of health service has its own characteristics. In a public health centre, midwives' maintain significant authority because of the involvement of general practitioners, who should provide a woman-centred service. In a hospital, the key decision-maker is a doctor, while the midwife is only an implementer (Indonesian Ministry of Health, 2020).

In 2021, the Indonesian Ministry of Health (2021) implemented a policy requiring all births to involve a multidisciplinary team consisting of doctors, midwives and nurses, in all three service settings (private midwifery practice, community health centre, referral hospital). This policy means that midwives do not have the autonomy to provide midwifery services independently, as they must be part of the team, and private practice midwives are not included in health service insurance. Although independent midwives can become part of the insurance network through collaboration with primary clinics (Silaen et al, 2020; Pan et al, 2022), it was reported that approximately 98% of independent midwives in Indonesia did not receive reimbursement from the national insurance scheme in 2021 )Pan et al, 2022). It is assumed that these independent midwives have not enrolled in the network (Pan et al, 2022), possibly as a result of the distribution of reimbursements at main clinics, delayed reimbursements and discrepancies in reimbursement values (Silaen et al, 2020; Pan et al, 2022). As a result, women who are covered by health insurance are more limited in their choice of where to give birth.

Aims

This study aimed to comprehensively analyse the interaction between birth place, philosophy and experience using an anthropological approach. Dahlen et al (2021) previously conducted a review of studies pertaining to birth place and philosophy. The authors created a unique concept, ‘running the gauntlet’, that emphasised the profound impact of birth philosophy on both healthcare professionals and women, decreasing dependence on technological interventions during birth. The present study goes a step further, and explores the impact of birth place and philosophy on birth experience.

Methods

This study used an ethnographic methodology where the process of childbirth was analysed based on the place of birth, surroundings and principles of the healthcare facility. The approach entails systematic participant observation and in-depth interviews, integrating the principles of philosophy of childbirth with the concept of birth place.

The study was carried out in two healthcare facilities in a city in Indonesia, one primary (a public health centre) and one secondary (a hospital). Public health centres prioritise preventive and promotive treatments, aiming to ensure that childbirth follows a healthy trajectory. Hospitals offer therapeutic treatments, unlike public health centres, which means they are equipped to handle birth complications. On arrival at a public health centre, women are admitted to the emergency obstetric care and neonatal basic facility, and given a designated birthing room. Hospitals admit women to the comprehensive emergency obstetric neonatal care unit, where birth will occur in a birthing room. In contrast with public health centres, hospitals are typically equipped with tools such as Holter monitors and electrocardiograms.

Participants

Women who were fluent in Indonesian and intended to have a spontaneous birth were eligible to take part in the study. Nulliparous and multiparous women were included, and snowball sampling was used to determine the number of participants included (Palinkas et al, 2015). Participants were recruited in their third trimester when they attended an antenatal care appointment or on arrival at a health institution during the latent period of labour. The latent period was assessed in a vaginal touch examination (1–3cm dilation).

A total of 14 women in the first stage of labour on arrival at the hospital were included. Two were excluded as they subsequently had a caesarean section. At the public health centre, five women were in the first stage of labour on arrival. However, one was excluded as she was then referred to the hospital.

Data collection

Data were collected between January and July 2024 through in-depth interviews, conducted by a midwifery lecturer and midwifery student, and observations, conducted by a midwifery lecturer and a midwifery practitioner. Participants were initially interviewed in the inpatient room within 1 week of giving birth, and follow-up interviews were held 42 days after birth to evaluate the sustainability of their childbirth experiences, at women's homes. Participants were accompanied by a second party (husband or family) for both interviews. Interviews were held at a convenient time and location for women.

The interviews used an interview guide to gather participants' perspectives on their encounters with maternity care providers, as well as their experiences with position and mobility during childbirth. The guide was created by the research team and validated through a consensus agreement process with the researchers and the midwives working at the hospital and public health centre. The questions included what the participants' perceptions of normal childbirth were, their expectations of what childbirth would be like and their most recent birth experience. The questions evolved accorsing to the needs of the research and the responses provided by the participants. Each interview lasted for 30–60 minutes and was audio recorded. The interviewer also kept written notes on the interviews. Interviews were held in Indonesian, and responses were translated into English by the research team, with consultation of an English expert.

Observations were done from the latent period of birth. Observers followed the birth process until participants were transferred to the inpatient room, recording all important events without intervening.

Data analysis

Observational field notes were analysed using systematic thematic analysis, which involved six stages: generating transcripts and getting familiar with the data, identifying keywords, selecting codes, developing themes, conceptualising through interpretation of keywords, codes and themes, and constructing a conceptual model (Naeem et al, 2023). The researchers initially analysed the data individually and subsequently collaborated to compare and observe their own and each other's findings, adding an additional layer of inspection. There were 12 themes initially, before collaborative analysis narrowed these down to seven themes.

Ethical considerations

All data were de-identified and codes were used to ensure anonymity. Ethical approval was obtained from Hajj Regional Hospital, East Java Province (reference: 445/038/KOM.ETIK/2024). Researchers provided information about the benefits, procedures and risks of data collection to the participants. When women entered the obstetric care unit at the hospital or birth centre, they were asked to provide written informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

The participants' characteristics are shown in Table 1. All participants who gave birth at the hospital experienced birth complications, while none of the participants at the health centre did so. Six of the participants at the hospital were planned referrals, who attended the hospital when labour began. The other six were referred by a public health centre or other clinics.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n=16) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital (n=12) | Public health centre (n=4) | ||

| Complication | Prolonged labour | 2 | 0 |

| High-risk pregnancy | 4 | 0 | |

| Hepatitis B | 1 | 0 | |

| Preterm rupture of membranes | 1 | 0 | |

| Postdate pregnancy | 1 | 0 | |

| Pre-eclampsia | 2 | 0 | |

| Chronic haemorrhoids | 1 | 0 | |

| None | 0 | 4 | |

| Parity | Primiparous | 5 | 3 |

| Multiparous | 7 | 1 | |

| Married | Yes | 12 | 4 |

| No | 0 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | Madurese | 4 | 3 |

| Javanese | 8 | 1 | |

| Education | Junior high school | 0 | 1 |

| High school | 8 | 3 | |

| University | 4 | 0 | |

| Health insurance | Yes | 12 | 4 |

| No | 0 | 0 | |

Philosophy of childbirth

Physiological birth

Childbirth was seen as a process that women must go through with the assistance of healthcare professionals. Rather than being considered part of the life cycle, it was seen as a health problem. Many of the participants felt that giving birth at a healthcare facility was safest because all the equipment needed was available.

‘In my opinion, giving birth should be done by a health worker. People used to do it with a traditional healer, many people died. If I gave birth at home, no one was watching. I didn't dare and was not afraid when my stomach contracts, I had to run to a health worker. In fact, sometimes I felt safe when I give birth in a hospital. It was full of equipment and complete’.

‘My mother gave birth at home, the baby was already out, the midwife just came. The baby was born safely. However, I didn't dare to do that, because if I gave birth at home, the equipment was not complete. I'm afraid something will happen, especially death’

Going with the flow

Some participants believed that birth was an unavoidable part of women's livecycle and contractions were an inevitable part of every birth, despite the intense pain.

‘Just like in previous childbirth processes, the more contractions, the better. I had to be patient. The midwife was very patient in giving me her understanding. I believed this is a form of worship that women go through’.

One participant was shocked by the pain of contractions, as she used to believe that the fetus she was carrying would not hurt her.

‘My child in my stomach did not hurt me, never vomited, I was sure he would not hurt me. But the doctor said the more painful it was, the better. It turned out my thinking was not right, it turned out it had to be painful for my child to come out. It turned out it really hurt’.

Technocratic birth

Two participants wanted a quick birth, and requested induction to quicken the process. One wanted a Kristeller intervention, which involved applying pressure to their abdomen during birth. One participant planned on having a caesarean section, as she believed it would alleviate the pain associated with birth. Relatives or close friends provided valuable information that women internalised into their childbirth paradigm.

‘When I was pregnant, I wanted a caesarean because I imagined that giving birth naturally would be painful. My friend also said that the contractions were very painful. But the doctor said that it could be done normally. But I felt pain, so I asked for a caesarean’.

‘My stomach was pushed yesterday by the midwife, but I wanted that so that my baby would come out quickly. I felt like my energy was helped by the push’.

Expectations and realities of birth place

Four participants wanted to give birth at a public health centre or with a private midwife. They had confidence in the midwives' ability to effectively manage birth and had a sense of ease when other women were present during the process.

Women's expectations of birth were sometimes impeded by birth complications, which necessitated referral to hospital, and health insurance policies that did not include women's preferred place of birth.

‘I wanted to go to the public health centre to get help from a midwife, but they referred me to the hospital. What else could I do? I felt comfortable being helped by a midwife because they were fellow women, so I didn't feel embarrassed. Besides they also definitely understand that giving birth is painful’.

‘My other children were born with the midwife, but I had no choice to stay here because there were many risks with my fetus and their age, and the third one also had problems’.

‘I had planned to give birth assisted by a midwife at the public health centre. I wanted to do it at the midwife's house, but my [insurance] was included in this public health centre, so I had to give birth here. There was one midwife who I felt comfortable with, but she did not work with [the insurance]’.

‘My mother gave birth in an independent midwife practice, so the midwife helped. However, now I can't access that, I have already joined [the insurance scheme]. I didn't know that now the midwife practice is not working with [the insurance scheme]. Finally, I can't give birth there, I don't have money to pay’.

Healthcare professionals informed women about potential hazards that could affect the woman and the baby, ensuring that the interventions provided were focused on ensuring their safety.

‘The midwife told me that if my fetus ran out of amniotic fluid, my baby will die. I only thought about my fetus; if I didn't go to the hospital soon something will happen. I didn't think about whether the hospital was comfortable or not, the important thing was that my child is safe’.

‘Everything went so fast, I was still hoping my dilation would increase. The midwife told my husband to take care of the paperwork, and immediately go to the hospital’.

‘I hoped to have a normal birth, even though I had a caesarean. But the midwife said I could check my pregnancy here, but I still gave birth at the hospital. It turned out that my delivery had to be caesarean again’.

Some women expected that they would give birth in a hospital and then needed to be referred, so they did not have to request their preferred birth place.

‘I did want to give birth in the hospital, but it just so happened that my pregnancy had to be referred, so without me asking, I was able to give birth here’.

The observations indicated that women could choose to give birth by caesarean section at the hospital, even in the absence of medical indications. Women were directed to antenatal care in the third trimester, so this could only be done for women who were referred to the hospital.

‘Women can choose a caesarean during antenatal care. This includes planned referrals, so they come when they are pregnant. Women are asked whether they want a vaginal or caesarean birth, then the doctor makes a diagnosis indication in accordance with the health insurance policy because this diagnosis would affect the cost claim on health insurance’.

The public health centre focused on preventing complications, so that women could give birth at the centre instead of being referred to the hospital. However, some women were referred to hospital when they could have given birth at the centre. This meant that women who would otherwise have given birth in a woman-led environment were exposed to a technocratic birthing environment instead.

‘Only a few births are in public health centres, many women who could have given birth here are referred. For example, women who gave birth with a haemoglobin level of 10g/dL during pregnancy are referred without re-evaluating their haemoglobin levels. Women came to give birth, but their amniotic fluid was cloudy, so they were immediately referred. Women with pre-eclampsia screening could be checked at public health centers, but later must give birth in the hospital. Women with previous surgeries must also be referred’.

Implementation of childbirth based on place

Two participants were not given the autonomy to choose a comfortable birthing position. They gave birth in the lithotomy position and the midwife told them to lift their legs and lower their head when pushing. Women's knowledge regarding choice of birth position was minimal, as the midwife did not provide education on this topic.

‘They instructed me to raise my legs and when I pushed, I had to look down and insert my hands into my legs. I never received any instruction about selecting a specific position … instead, I adhered to the midwife's instructions. I only learned that you shouldn't push yourself up during labour. The nerves play a role in this situation’.

‘I followed the midwife's orders to lift my legs and lower my head during the pushing process’.

However, some women did not feel that having a choice of birth position was important. They reported feeling that the lithotomy position was the safest or that the midwife would choose the safest position.

‘My position was still in bed, I followed the midwife. The important thing is that I am safe’.

‘I had heard that the birthing position could be chosen, but I didn't think it mattered. The midwives here could measure’.

Women in the public health centre had more opportunities to mobilise compared to those in the hospital, in part because of the monitoring equipment used at the hospital.

‘I stayed in bed, didn't walk around. The reason was because there was a recording of the fetal heartbeat’.

‘I was told to go for a walk, I don't have to be in bed. In fact he said I had to go for a walk so the opening process will be faster’.

According to the observations, women who gave birth at the hospital often lacked assistance from their husbands or family as it was felt necessary for the area to be free from external contaminants. This meant some women were left to endure pain in solitude. Hospital standards required contacting husbands and families to obtain approval for treatment, meaning women lacked complete autonomy in determining the operations they underwent.

‘I saw her lying in some beds covered with curtains, without her husband and family, so she had to go through the pain herself. At times, a family may visit to obtain a signature or provide the woman with necessities such as food or goods. Sometimes any action obtained by the mother is unknown to her, discussion only occurs between the husband and the health officer’.

‘Births in public health centres still use high beds, but women give birth in a separate room. However, the room looks very much like a medical room full of maternity guides and references, as well as being close to centralised medicine’.

‘I wanted to be accompanied by my husband but I was not allowed because there were other patients. I was disappointed, I wanted to be accompanied by my husband’.

In contrast, at the public health centre, husbands and family members were allowed to offer complete assistance during birth. The husband had a vital role in providing support, as they not only provided consent but also served as a companion. Women were allotted additional time for deliberation over procedures they underwent, granting them complete authority.

‘The husband accompanies during contractions until the baby is born. He always accompanies fully when the childbirth process is long, even the dilation is long. The midwife provides … space for interaction between women and their families. Women are actively involved in the decision-making process’.

‘The midwife actually asked for my husband's presence, my husband had to feel the contractions that I was experiencing. My husband accompanied me when I was pushing until our baby was born. This support really helped me to get through the pain during the childbirth process, I was not alone’.

Hospital births tended to be technocratic. Doctors performed medical interventions and one participant experienced slow cervical dilation but had not yet entered the prolonged category, and was still recommended to undergo an operative birth via caesarean section.

‘The woman was still at 4cm dilation, an internal examination was carried out 4 hours later and it was still 4cm dilation. However, after we analysed it on the partograph, the condition had not passed the alert line, which meant the mother still had a chance to fight. However, I saw the midwife calling the doctor for a consultation on dilation, the doctor gave advice to perform a caesarean childbirth’.

Experience based on place of birth

The experiences of women in the hospital and public health centre varied. Participants from the public health centre generally did not have painful experiences and the process was perceived to be fast and enjoyable.

‘The birthing process was very fast, the pain was not long. I did not feel excessive trauma’.

Women who gave birth in the hospital often experienced trauma. Some procedures were perceived as highly distressing, including suture repair and curettage (aspiration or removal of tissue in the uterus). Some participants required sutures because of a retained placenta, which caused significant distress because this procedure was frequently conducted without support from spouses or family. Participants lacked understanding of the procedures, and healthcare professionals were felt not to have provided sufficient interaction and communication, resulting in a lack of awareness.

‘I was anxious when I was going to be stitched again because it hurt. I prayed for 30 minutes … The blood was still coming out at 10 o'clock. Finally I was given medicine. I didn't know, the light came on and the equipment for stitching came out, I imagined I had to feel the same pain. Then the cloth was inserted, then the blood was checked, it came out according to the midwife's wishes, it turned out that the injection earlier could prevent it. I didn't know I was given fluids two times, waited 5 minutes, it turned out the blood came out. When it was inserted, it felt really painful’.

‘This sticky placenta traumatised me. Suddenly there was a hand that entered my vagina, I only heard the midwife's voice. The midwife only spoke to another midwife, she said this is dangerous, must be curetted. Suddenly I came to and there was no one at all, it hurt so much’.

‘I was not asked for consent for the curettage, and I was not given any information. Suddenly, a lot of blood clots came out, my head felt dizzy and I realized I was sitting with my legs open’.

The doctor was the primary authority responsible for decisions in the hospital. Midwives consistently communicated with the doctor about a woman's condition but this communication did not involve teamwork. Midwives typically served as assistants to doctors. In some cases, midwives prioritised saving women's lives in emergency circumstances, resulting in a lack of provision of respectful maternity care.

‘The midwife reported to the doctor that the patient was bleeding. The doctor was not in the hospital at that time, the midwife communicated all this by phone. After receiving the phone call, the midwife called the women's husband and asked him to sign. The process was very fast, and the women was not given any information as to why this action had to be taken. The emergency situation made this happen so quickly’.

Although both settings had cases where the perineum was sewed, different forms of communication were used by midwives across the two settings. At the public health centre, women were often women to communicate to alleviate pain. Midwives in hospitals often prioritised completing the process as quickly as possible.

‘The stitches made me hurt, even though I was anesthetised, it still hurt. But the midwife invited me to chat, at that time the midwife asked me questions about my life, I got distracted, suddenly it was over’.

‘Stitches in the vagina hurt so much’.

‘When I was stitched up, I didn't use anesthesia, it really hurt. And it turned out to be swollen, all the blood was drained. The midwife didn't say whether it was with anesthesia or not’.

Women may experience discomfort from stitches over the postpartum period and some reported that they had no desire to conceive again because of their apprehension regarding sutures. Participants who had extensive medical interventions, such as stitch repair and curettage, experienced a greater degree of trauma. However, the majority did not find the process of giving birth traumatic.

‘The stitches still hurt until now. I'm afraid of getting pregnant again. However, the contractions could still be tolerated, the process can be enjoyed’.

‘The process went smoothly and quickly, but the stitches made me a little traumatised. It hurt a lot’.

‘I hope my next pregnancy will not be curettaged, I felt like my life and death were on the line when the curettage was performed. I hope my pregnancy will be normal, not in the hospital again’.

Interplay between philosophy, experience and place of birth

Each woman has her own beliefs about childbirth, shaped by her philosophy, which will influence selection of the birth location. However, women may not be able to give birth at their chosen location because of the limitations of the healthcare system and the specific circumstances of their pregnancy. In Indonesia, women with high-risk pregnancies are referred to a hospital. The Ministry of Health imposes strict referral standards that can prevent women from giving birth at a public health centre.

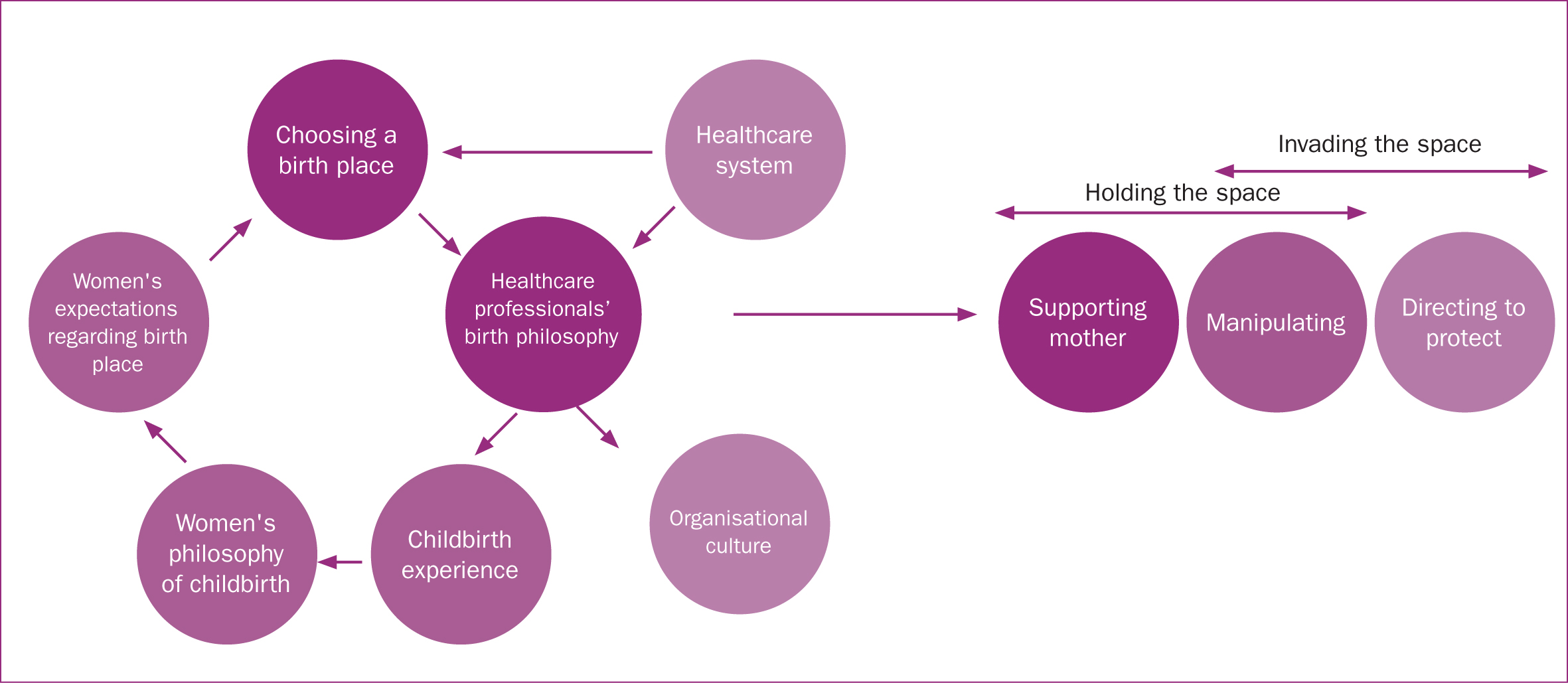

Birth involves the convergence of a woman's childbirth philosophy and the perspectives of healthcare professionals, such as midwives and doctors. Healthcare professionals' opinions are shaped by the service system and organisational culture of healthcare facilities. Doctors play a crucial role in the birth process in hospitals and had the authority to permit elective caesarean section, even in the absence of compelling medical reasons for a caesarean. A disparity between a woman's childbearing philosophy and that of healthcare workers can create difficulties and negatively affect the birth experience.

Childbirth at a public health centre can present challenges. Midwives in this setting are committed to preserving the naturalness of childbirth. This experience will be a determining role in shaping women's childbearing philosophy (Figure 1).

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between women's birth philosophy, the place where they gave birth and their experiences. Women's childbirth philosophy affects their expectations regarding birth place, support from healthcare professionals and their approach to giving birth.

Physiological birth is typically linked with care provided by midwives, while technocratic birth is usually associated with care given by doctors (Wilson and Sirois, 2010; Preis et al, 2018). The woman-centred and technocratic models of care diverge in several ways, as the medical model of care uses a ‘problem management’ strategy, resulting in frequent medical interventions and greater reliance on technology (Howell-White, 1997).

Expectations

Childbirth expectations are affected by biopsychosocial factors, including whether women have an optismistic or pessimistic view. Women with a pessimistic view may focus on the risks and possible negative experiences, leading to the belief that medical interventions are necessary. Conversely, if women believe that birth will be safe and their babies will be healthy (Lobel et al, 2002), they may be less likely to request interventions. The biopsychosocial model theory also posits that social context has a significant impact on women's ideas about the birth process (Preis et al, 2018). Women's perspectives on birth might be shaped by their local social environment, as friends and family members recount their experiences of giving birth, establishing a standard for managing the process. This can result in exposure to distressing narratives and a general sense of concern for the wellbeing of the baby (Fisher et al, 2006; Preis et al, 2018).

The present study's participants expressed disappointment when their expectations were not met, particularly when giving birth in the hospital. Some found that complications during childbirth prevented them from giving birth in their preferred location or with their chosen healthcare professional, some were not able to have their husband present because of hospital policies and some were surprised by the pain of their contractions, as they had believed that their fetus would not hurt them. Failure to meet expectations can significantly contribute to a negative birth experience, particularly in cases where women are not given the ability to make their own decisions.

Many participants wanted to give birth accompanied by a midwife, but this was not always possible. Some could not because private midwives were not part of their insurance scheme. In Indonesia, it has been shown that the minimal reimbursements received by midwives, especially for childbirth services, discourages them from joining the scheme (Strategic Purchasing for Primary Health Care, 2020). However, women using health insurance when giving birth must choose a participating health facility, limiting their options. Public health centres can accommodate women's wishes to be accompanied by a midwife, but observations from the present study highlighted that some women were referred to hospital, meaning their care was managed by a doctor, even when a physiological birth would have been possible.

The pain of contractions can lead to trauma (Gustafsson and Raudasoja, 2024), which can be intensified by birth complications. However, positive communication and support from healthcare professionals can reduce trauma (Carroll et al, 2016; Falk et al, 2019; Hammond et al, 2022) and it has been reported that women with a physiological birth philosophy are less likely to be affected in this way (Dahlen et al, 2021; Gustafsson and Raudasoja, 2024). Healthcare professionals should offer constructive advice to address women's anxieties about complications (Coxon et al, 2017).

In both the hospital and public health centre, women highlighted that they felt that healthcare professionals did not effectively communicate with them and they did not feel included in discussion processes. Unsupportive services can also lead to disappointment, in addition to expectations not being met (Viirman et al, 2023).

Elective caesarean section

The study highlighted existing behaviours that were not conducive to woman-centred care. In the hospital, observations found that doctors endorsed caesarean section, undermining the ability to have a physiological childbirth with minimal medical intervention (White, 2022; Papoutsis and Antonakou, 2023). Caesarean section without medical indication can result from the overmedicalisation of birth, which is closely aligned with technocratic philosophy (Miller et al, 2016). In addition, it has previously been shown that the health insurance policy in Indonesia incentivises physicians and health facilities to perform caesarean section (Teplitskaya and Dutta, 2018; Al Farizi et al, 2022). Doctors should ensure that women are fully informed of their options and the benefits of physiological childbirth over a surgery that is not medically indicated (Sorrentino et al, 2022).

Indonesian policy

Indonesia's referral policy meant that high-risk pregnancies were referred to hospital, even when a woman wished to give birth elsewhere, inhibiting women's autonomy. In this context, healthcare professionals have greater authority over decision making regarding women's care than women have themselves (Coxon et al, 2017).

The aim of the referral policy is to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality, and, in emergency situations, it is important to prioritise safety and ensure easy access to necessary medical equipment. Australia uses a similar system, where women identified as ‘high risk’ and those with chronic diseases have limited options when choosing place of birth, while low-risk women can give birth at centres that focus on women's needs (Naughton et al, 2021). However, it has been shown that some women are disappointed by the lack of choice to give birth outside a hospital (Australia Department of Health, 2009; Naughton et al, 2021), which was reflected in the present study's findings. Conversely, in the UK and the Netherlands, women with high-risk pregnancies are able to choose where they give birth, including to give birth at home (Christiaens et al, 2013; Lee et al, 2016). Ideally, women should have the autonomy to choose where they wish to give birth.

Organisational culture

Organisational culture and the health service system impact the birth service model offered to women. Midwives working in hospitals can face difficulties aligning their services with the principles of physiological birth or following the natural course of labour (Behruzi et al, 2013). Midwives at public health centres prioritise government-led initiatives aimed at mitigating maternal mortality, meaning that women's safety, rather than their comfort and autonomy, are prioritised. Doctors are present at all births in public health centres and hospitals, including in both typical and abnormal circumstances (Indonesian Ministry of Health, 2021) General practitioners are consultants in referral decision making at public health centres, while obstetricians are the main decision makers for hospital services.

Midwives have greater authority at public health centres than in hospitals. In this setting, midwives are able to incorporate a physiological birth philosophy, while in the hospital, doctors assume the role of the primary decision-maker during birth. However, the present study's participants highlighted that in public health centres, midwives made decisions without consulting the woman giving birth, for example by placing her in a particular position for birth. Additionally, the Kristeller maneuver was used during some participants' births, which is controversial; one study found that it can increase the risk of levator ani muscle injury (Youssef et al, 2019). Nevertheless, women were given greater autonomy at the centre than the hospital; they were able to have a birth companion and were free to move around. Support from a family member, such as a woman's husband, is important (Hoffmann et al, 2023), especially for those with complications. Midwives should provide assistance but should not lead the birthing process, as was the case in public health centres in the present study.

Limitations

This study explored women's philosophy of childbirth, but not that of the healthcare professionals who provided care. Furthermore, the study was only conducted in two healthcare settings, and did not include tertiary hospitals.

Implications for practice

Indonesia should implement midwifery led care for birth. However, to do so, midwives must be given the flexibility to provide services independently and should be trained to provide this service model. In addition, birth planning is important to increase women's autonomy over their bodies.

Conclusions

A woman's childbirth experience is shaped by the interplay between her childbearing philosophy and the birth environment. The characteristics of childbirth facilities vary depending on cultural norms and organisational practices, which also influence the childbirth philosophy of healthcare professionals. While midwives often support a woman-centred model of care and physiological childbirth, they are constrained by the system in which they practice. In addition, this system can affect women's views, discouraging physiological childbirth in a medicalised setting.

While prioritising prevention of maternal mortality, it is also crucial for birthing facilities to be tailored to women's needs. Adverse birth experiences can negatively impact a woman's wellbeing and that of her children. An empathetic system is needed that takes into account women's preferences and promotes physiological childbirth.