Breech presentation at term gestation has been estimated to occur in 3%-5% (1:25) of pregnancies (Hannah et al, 2000; Walker et al, 2018a) with very few of these resulting in a vaginal birth. Following the recommendations of the ‘Term Breech Trial’ (TBT) by Hannah et al (2000), most developed countries almost immediately changed policies to advising women to choose a planned caesarean section for breech presentation based on the results regarding safety, morbidity and mortality. Much debate has ensued since the publication by Hannah et al (2000) regarding the methodology of the study and follow-up outcomes (Lawson, 2012; Sloman et al, 2016; Walker et al, 2018a). The speed of change suggests this was the permission practitioners were waiting for to move away from vaginal breech births with the implementation of planned caesarean sections leading to a quick reduction in the number of skilled clinicians familiar with vaginal breech births (VBBs) on a global scale.

The TBT (Hannah et al, 2000) and recent research (Catling et al, 2016; Walker et al, 2018a; Carbillon et al, 2020) address the presence of a skilled clinician in VBBs as the most important factor in the safety of a physiological labour and vaginal birth for breech presentation. In the 20 years since the TBT, it is recognised that women continue to want a VBB when counselled on the risks of both caesarean section and VBB (Hofmeyr et al, 2015; Sloman et al, 2016). However, it is unclear as to how much bias is expressed in the consultations with women and their choice for mode of birth. The problem now faced is that the skilled clinicians are not readily available, which is limiting women's autonomy over birth choice and risking safety.

More recent evidenced-based VBB training discuss the physiology of breech and movement through the pelvis in order to provide clinicians with a working knowledge of the mechanisms as the breech is birthed. Maternal positions (ie upright and all-fours positions) are considered to enhance pelvic diameters and descent (Walker et al, 2016a; 2016b). It is anticipated that understanding these two components through education will enhance a practitioner's skill and confidence.

Walker et al (2016a; 2016b; 2018a; 2018b) have conducted a collection of qualitative research into the development of expertise in VBB. Sloman et al's (2016) qualitative study also considered the experience and confidence of practitioners that see themselves as specialists. The participants in their studies were regarded as ‘breech specialists’ or ‘experts’, with most having experience of more than five VBBs and some with over 20 VBBs. However, there remains a gap in the understanding of attitudes and perceptions of midwives who have not gained the competence in VBBs.

One can question if current training is enhancing VBB skills and if it addresses the factors that influence midwives to pursue competence. Although confidence was explored by Sloman et al (2016), confidence is one aspect relating to competence, with self-efficacy and knowledge also being contributing factors (Bäck et al, 2017).

The Nursing and Midwifery Council ([NMC], 2019a) states midwives need to be able to initiate additional care until help is available, which includes ‘conducting a breech birth’. Therefore, an understanding into the factors that influence confidence and competence will aid educational programmes and institutions to deliver appropriate training and foster an interest in VBB to promote overall safety of the mother-baby dyad. The aim of this study was to identify influencing factors in VBB skill acquisition for midwives in order to address potential barriers and promote skill attainment and competence.

Methods

An exploratory qualitative design was chosen to articulate an understanding of the experiences of midwives influencing skill acquisition. An exploratory methodology was chosen to gain a better understanding of influencing factors, exploring the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of experiences (Braun and Clarke, 2013). As exploratory research does not produce conclusive results, the findings may be used as a basis for future studies on the topics that arise. Ethical approval was gained through the University of Southampton. Midwives were chosen as the participants in this study in order to focus on factors influencing their skill attainment. The experiences of women choosing a VBB were not explored for this reason; however, future research of their experiences would be beneficial to practitioners' understandings of the woman's experience.

Sampling, recruitment and participants

Participants were registered midwives currently practicing in the UK to meet inclusion criteria. The decision to exclude non-practising midwives or those practicing outside the UK was due to changes occurring in breech birth education. The rationale for this exclusion is the offering of physiological breech birth training by the Breech Birth Network to numerous NHS Trusts in the UK and the inclusion of upright breech birth management within mandatory training days. These are examples of how training in breech birth management is altering from previous practices (non-practicing midwives), also non-UK-based midwives may not have had access to these training packages. Purposive sampling was used to ensure participants had limited experience in VBBs in order to identify the influences on skill attainment for those not considering themselves experts or specialists.

Initial recruitment was via posters displayed at the University of Southampton and local NHS Trust maternity departments and then displayed on social media in a private group with permission of the group's administrator. There was little initial interest in participation and no follow through from those that expressed interest in the initial recruitment phase. During the recruitment phase, the global COVID-19 pandemic was becoming a growing concern, therefore alternatives to recruitment and data collection were made, and the ethics protocol amended with participants being more willing to take part as the data were collected via a Microsoft Teams meeting.

A total of five midwives expressed interest in participating; however, on the day, one participant did not log on for the meeting. Four participants were registered UK midwives with more than five years clinical experience (Table 1), with three facilitating less than five VBBs and one participant who had notable historical experience in VBB. The decision to allow inclusion of an experienced practitioner was due to recruitment difficulty and the depth of understanding in changing skills practices pre- and post-TBT as they were practicing midwifery at the time of TBT publication.

Table 1. Participant demographics

| Years of experience | Witnessed VBBs | Facilitated VBBs | Current area of practice | Training courses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW1 | 10+ | 6 | 3 | Acute hospital | In-house NHS Trust training, PROMPT, physiological breech birth |

| MW2 | 5–10 | 5+ | 0 | Midwifery educator | In-house NHS Trust training, PROMPT |

| MW3 | 10+ | 50+ | 20+ | Midwifery educator | Independent VBB training/study day |

| MW4 | 10+ | 2 | 0 | Midwifery educator | In-house NHS Trust training, PROMPT |

The midwives were randomly assigned as MW 1–4, as they did not wish to choose pseudonyms themselves.

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected using a focus group via Microsoft Teams and recorded with consent using the built in feature following a semi-structured format with prompt questions, such as, ‘what are your first thoughts about the term vaginal breech birth?’ The focus group facilitated discussions about the experiences in practice, providing rich data and shared feelings as they emerged, which were then debated and justified, leading to an empowering experience (Conradson, 2005; Cluett and Bluff, 2006; Krueger and Casey, 2015). This method was chosen due to lockdown measures instituted by the UK government in response to the threat of COVID-19.

2.3. Data analysis and interpretation

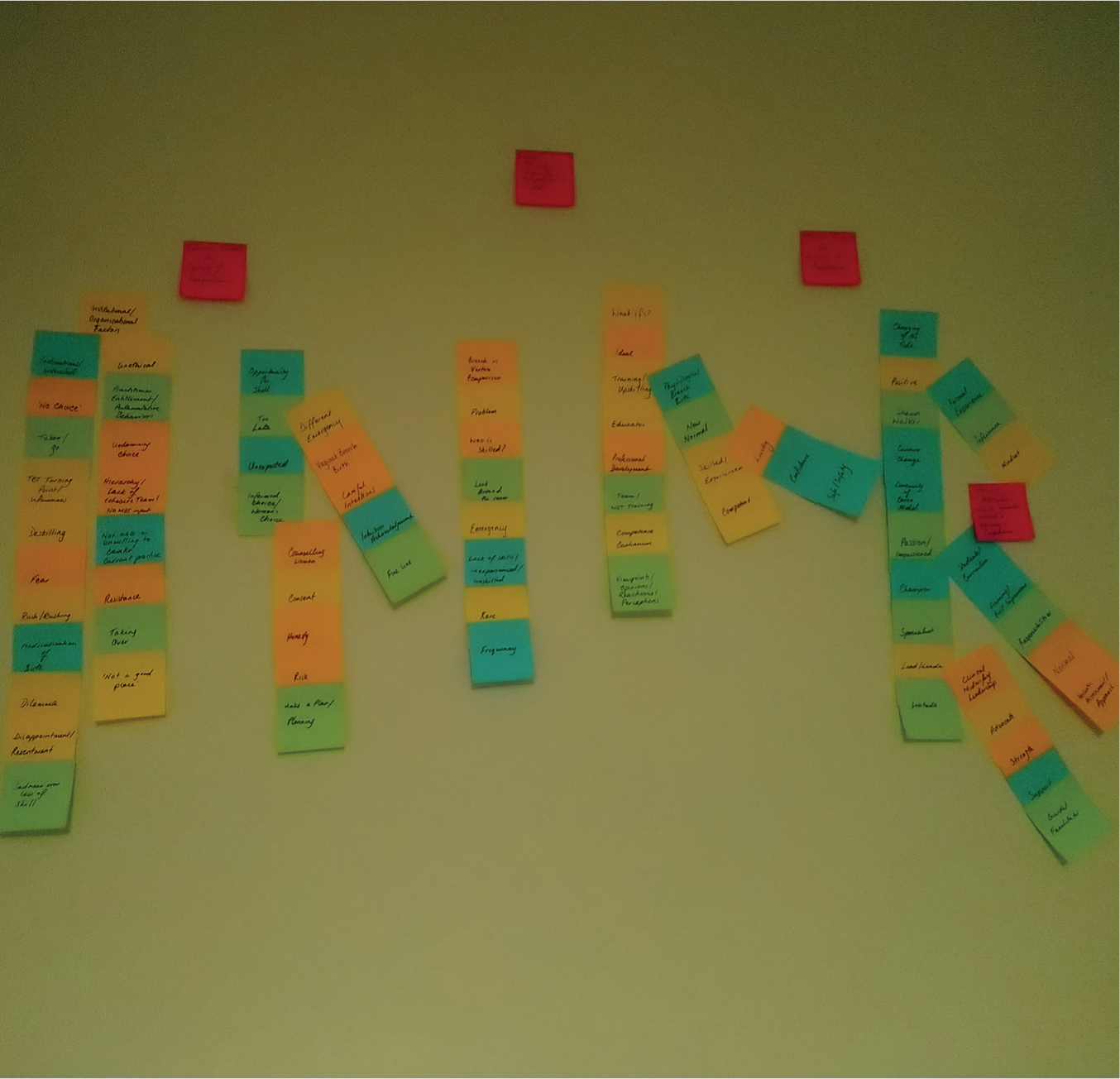

Braun and Clark's (2006) method of thematic analysis of the data was used to formulate findings. Data were transcribed using Microsoft Teams transcription service and verified for accuracy by VF. Notes were made during the focus group and transcription verification before detailed coding was commenced. The transcription was read several times with an initial list of 80 codes made. All codes were placed on a wall (Image 1) and grouped into subthemes initially and then into overarching themes (Image 2). This process was reviewed by the research supervisor EKR. Three main themes evolved from the analysis process (Table 2): ‘not a good place’, ‘changing the tide’ and ‘new normal’. These themes represent a continuum of influences on VBB practice and are explored in nine subthemes. Terminology for the themes came from direct phrases used by the participants.

Image 1. Coding process

Image 1. Coding process  Image 2. Grouping of subthemes

Image 2. Grouping of subthemes

Table 2. Development of themes

| Initial notes | Sub themes | Main themes |

|---|---|---|

| Deskilling, dilemma, disappointment or resentment, emergency, fear, fine line, framing, frequency, hierarchy or lack of cohesive MDT, institutional or organisational factors, instructions, lack of skills or unskilled or unexperienced, look around, medicalisation of birth, mindset, no choice, not a good place, not able or willing to counter current practices, practitioner entitlement or authoritative, problem, rare, resistance, risk, rush or rushing, sadness for loss of skill, safe or safety, taken or goes, taking over, TBT turning point and influences, too late, undermining choice/coercion, unethical, who is skilled? | DeskilledFearNo choice | Not a good place |

| Different emergency, education, framing, frequency, guide or facilitator, holistic assessment or approach, honesty, ideal, influence, informed choice or women's choice, institutional or organisational factors, intuition acknowledgement, lead or leader, lucky, mindset, normal, opportunity for skill, passion, personal experience, plan, positive, professional development, responsibilities, safe or safety, shawn walker, skilled or experienced, specialist, strength, students curriculum, support, team or MDT training, training or upskilling, vaginal breech birth, viewpoint or opinion or reaction, what ifs | What if?Women's Choice Champions and Clinical Midwifery Leadership | Changing the tide |

| Education, framing, frequency, guide or facilitator, holistic assessment or approach, ideal, influence, informed choice or women's choice, institutional or organisational factors, intuition acknowledgement, lead or leader, mindset, new normal, normal, opportunity for skill, passion, personal experience, physiological breech birth, plan, positive, professional development, responsibilities, safe or safety, shawn walker, skilled or experienced, specialist, students curriculum, support, team or MDT training, training or upskilling | Physiological Breech Birth Pre-Registration student education | New normal |

Findings

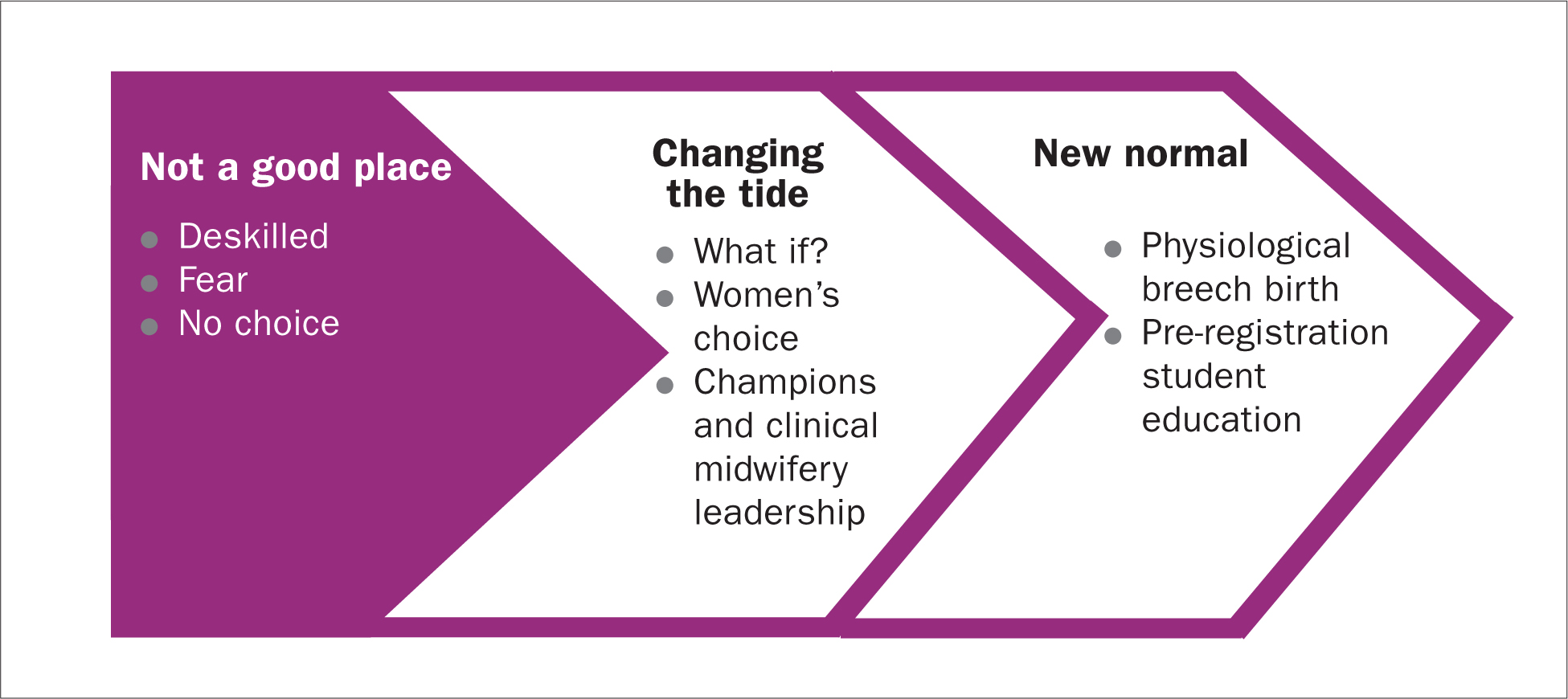

The three themes that emerged from the data formed a ‘continuum of change’ (Figure 1). The themes move from skills in VBB not being common, to the coming of a new age of practice where specialised evidenced-based training is gaining ground.

Figure 1. Continuum of change

Figure 1. Continuum of change

Not a good place

Following the TBT, there was essentially an overnight change in practice for the management of breech presentation. This change happened very quickly; one participant who was practicing at the time of the change felt it left the birth environment in a tough situation with unskilled practitioners:

‘So, we've come to a place which is really not good which is where people just don't have the skills’

–MW3

This was the turning point of VBBs being considered a variation of normal to an obstetric emergency. The change was brought on by a swift deskilling of practitioners and fear, leaving women with no choice in birthing options which are shown in the subthemes.

Deskilled

Due to a lack of confidence, practitioners then began to fear a VBB. Becoming deskilled directly affected practitioner confidence:

‘But the problem is now obviously … nobody is really feeling very confident in actually facilitating a vaginal breech birth’

–MW2

The participants discussed having the experience of an uncomplicated VBB as a factor influencing normality and confidence. For instance, one practitioner discussed the seminal work of Mary Cronk, a well-known independent midwife with experience in breech births:

‘She would have been considered to stretch the rules a bit … did she actually take on more than she should have done and how risky was that? A true advocate for women.’

–MW3

The confidence to support others in practice is also determined by the experience of the leading practitioner, according to the participants. Therefore, with a lack of skills, most practitioners would not feel confident in mentoring a colleague, which further deskills all practitioners.

No choice

The TBT led to an authoritarian view of breech management which striped women of the right to choose the birth they wanted. One midwife described this as:

‘…instructions were issued … it wasn't even about informed consent … women that had a breech presentation must have a caesarean section.’

–MW3

Most of the midwives were able to recall situations in practice of the woman being ‘taken’ or ‘rushed’ to theatre when presenting with an eminent breech birth even if it was not their choice.

‘I've known women being rushed off to theatre when probably they didn't need to … hadn't even been her first baby or anything’

–MW4

One midwife put into words the resignation or reluctance of midwives to alter the status quo due to power distance and hierarchy as well as the overall unit mentality:

‘But that's how it is now isn't it’

–MW2

The resignation of midwifery autonomy thus feeds down to choices presented to a woman with a breech presentation. One midwife commented on how external factors of the labour ward may take this choice away, with reference to the current pandemic:

‘A lot will depend on the situation in the maternity unit at the time. I mean, for instance, now (referring to COVID-19 pandemic) I don't know. If a woman wanted a breech birth now, that would be impossible.’

–MW3

Changing the tide

In recent years, there has been an increase in the research conducted on VBB and the woman's voice in maternity care leading to a rise in the profile of VBB and informed choice. By raising the profile, a change in service provision and education has begun to occur but is reliant on the continued efforts of practitioners to further the cause. Subthemes focus on factors that are initiating a movement towards enhancing VBB education and facilitation. One midwife gave the following description:

‘…there is becoming a kind of changing of the tide … there are some really passionate midwives and obstetricians out there now who are trying to change that tide … you might be changing that tide but until you've got people with experience who can kind of lead that way forward, it's just gonna hit a brick wall really.’

–MW2

What if?

When discussing participants' initial thoughts on VBB, one participant felt strongly that VBB is an obstetric emergency while the others played ‘devil's advocate’ with the use of ‘what ifs’.

‘…if it wasn't put with those obstetric emergencies in terms of training. And if women weren't advised to have a caesarean section if they were found prior to delivery, prior to labour to have a breech presentation then do you think we would see it differently? Probably.’

–MW2

This thinking is an influence on the mindset of practitioners and one participant discussed how VBB is initially ‘framed’ to the practitioner and how they would view an eminent breech birth. What ifs also came up when discussing pre-registration training structure and how framing may affect future midwives' perceptions.

‘Perhaps your mindset would be different … but it's about how it is framed and presented to you initially.’

–MW2

The change in mindset and framing of VBB from an emergency to a variation of normal is influential for training structure and counselling of women with breech presentation.

Woman's choice

The midwives discussed the influence of the woman on training uptake for practitioners. One midwife discussed how her hospital put in place mandatory training in VBB skills because one woman wanted a VBB and they needed to be able to facilitate that for her. Another midwife felt it was the responsible action to take.

‘I think if women are choosing vaginal breech then we do have some responsibility to be able to provide it for them.’

–MW4

However, one midwife discussed that the woman's choice is not always respected, and practitioners use methods of coercion to change her mind, thus undermining her.

‘She's looked into it; she's decided that that's what she wants … If they are informed and part of being informed is being up front and honest about the skill set of your staff … then if the woman still wants to go ahead and have a vaginal breech birth then that would be her choice and we would facilitate that. That doesn't mean they wouldn't try and convince her the other way. We do see that happen.’

–MW2

There was also discussion on how the woman's choice to have a VBB provides an opportunity to practitioners for skill development. Where a woman is not in a catchment for a specialist breech service, some women may decide to go to another area that can facilitate their choice. One midwife discussed how inequalities may affect a woman's choice and birth outcomes in this scenario:

‘If the woman's got the ability to do it … the woman will go and find somebody. But that does mean that somebody who can go and find somebody will have more chance of having a breech vaginal birth than somebody who doesn't understand that process.’

–MW3

With the progression of the UK's commitment to providing continuity of carer, one midwife felt this may affect the options for women:

‘I mean moving forward into the better births and continuity of carer schemes that are developing, some of this will depend upon the views of the midwife that's providing the continuity of care … then what she says and what she believes in, what sort of informed choice she gives the woman will have a huge impact on what happens at the birth.’

–MW3

Clinical midwifery leadership entails being an advocate for the woman and her choices thus promoting respect.

Champions and clinical midwifery leadership

Champions are the practitioners leading the change for greater service provision and training. One midwife gave a clear description of a champion:

‘Somebody who really believes passionately in it and who organises the staff, both doctors and midwives, to be able to do that training and to give them confidence. You need somebody that has actually done it to be the centre of a team … that would give the unit confidence too.’

–MW3

Another midwife discussed an ideal situation for champions to upskill others:

‘I think the ideal situation would be for a midwife who wasn't experienced in it to be able to actually facilitate that birth with someone standing behind them who was. And then you would end up with more people who had that experience. Then actually the room would be safe because they would intervene if necessary, rather than just taking over.’

–MW4

The participants discussed the role of clinical midwifery leadership as beneficial to education and support of practitioners and women in facilitating a VBB, and provide a beacon to the midwifery profession while also including the multidisciplinary team. One midwife discussed how a consultant midwife with breech expertise would be suited to taking this role. Another midwife spoke about a breech specialist team's role in clinical midwifery leadership, which is discussed by Walker et al (2018a).

‘You have specialists … and then they have a team, you know. And then they can pass on their skills too. I think that would work really well. That's what we need.’

–MW1

Clinical midwifery leadership appears to be responsible for bringing together the champions and novices to promote skill attainment, teamwork and unit proficiency in order to provide greater service provision.

New normal

Twenty years after the publication of the TBT, a change is happening for VBB, which would not have been possible without the work of champions advocating for women's choice. As one midwife stated:

‘This is the new normal. Like the new way that it's going to be done, and this is going to be what students are going to be seeing in clinical practice then actually it is so important that all of us go and hear that.’

–MW2

The new normal for VBB is dawning as education is enhanced and disseminated. The subthemes focus on the context of education as influencing current and future practitioners' skill development.

Physiological breech birth

Throughout the focus group discussion, there was a different meaning associated to physiological breech birth as opposed to vaginal breech birth. Generally, the midwives used the term physiological breech birth when discussing breech birth as a variation of normal and VBB when it was considered an emergency.

‘Vaginal breech birth is an emergency … even though we have the new one by Shawn Walker, the physiological breech … she did physiological versus abnormal because obviously it can be physiological if the baby's in the right position … I was a bit apprehensive about attending her study day because as I said at the beginning, to me breech vaginal breech is an emergency.’

–MW1

As Dr Shawn Walker's training programme is titled ‘Physiological Breech Birth’, with specific teaching towards upright and all-fours positions for breech birth, it seems that midwives are associating the term with normality and holistic care. Physiological breech birth training appears to be being taken up by practitioners, from student midwives to consultant obstetricians, therefore upskilling everyone, which creates a levelling of experience and reduces power distance (Leonard et al, 2004; Magee, 2020). It has been seen in practice that all levels of staff are attending physiological breech birth training when it has been offered by NHS Trusts in the form of study days and mandatory training. In the quote from MW1, there was the expression of apprehension over attending the study day, which may be a similar opinion of other midwives, potentially influencing the uptake of training programmes and thus dissemination of skills for facilitating any form of VBB.

Pre-registration student education

The participants all vocalised having a role in pre- or post-registration education of midwives. Discussion on how to conduct student education on VBB was an influence on their own learning and confidence in VBB and how they portray VBB (ie obstetric emergency or variation of normal). One midwife felt that universities are a contributing factor:

‘Should all universities be taking breech out of its emergency curriculum and putting it into normal? The role of the universities-that's going to be really important. How we train our students.’

–MW3

Another midwife spoke about when training should happen if there is to be a change in opinions on VBB and what format this might take.

‘If we just go back to the beginning when we are starting to teach about the physiology of labour, we could possibly focus more on the physiology of a breech birth as if that's a normal process. If we wanted to try and bring a more normal focus … we should be looking at that earlier in the curriculum.’

–MW4

Changes to curriculum may affect the upcoming workforce's mindset on VBB and upskilling of practitioners.

Discussion

While some of the influences discussed in this study may be considered negative ie fear and no choice, these were regarded as drivers for change as expectations of shared decision-making and multi-disciplinary training are reducing the power distance of practitioners (Leonard et al, 2004; Magee, 2020). Jomeen et al (2019) discuss the positive outcomes of maternity training on confidence and knowledge which in turn provides the skills necessary for advocating for women.

As the woman's voice is growing and informed choice is being utilised, women are becoming more empowered to be in control of their birth choices (Elwyn et al, 2012; Ashforth and Kitson-Reynolds, 2019). The move away from dictatorship following the TBT in the early 2000s is changing the tide of how a woman is involved in her care. The ‘Better Births’ (National Maternity Review, 2016) initiatives and implementation of increased continuity of carer in the UK is supportive of women's choice.

Continuity of carer was highlighted as having the potential to positively influence a woman's choice if the midwife or team are supportive of VBB and have the expertise needed for a safe outcome.

Walker et al (2018b) discussed how practitioners seek out opportunities to learn and develop their expertise in physiological breech birth which aligns to the use of champions and clinical midwifery leadership in this study. These were considered as positive influences on skill attainment as their passion and expertise creates a positive and safe learning environment. The quality of leadership is directly related to outcomes in complex situations with poor leadership resulting in worse outcomes (Cornthwaite et al, 2015). The role of clinical midwifery leadership can lead to better outcomes by utilising their knowledge base and being supportive of upskilling practitioners, which may be exemplified by the development of breech specialist teams and services.

The NMC (2019b) discusses the need for students to conduct spontaneous deliveries of breech babies in urgent circumstances under supervision of a registrant. The NMC (2019a) also discusses the need for registered midwives to conduct a breech birth while additional help is sought. Therefore, the format of pre-registration education will need to reflect the competency expected of the registering body. This ‘new normal’ will need to encompass both physiological breech birth and emergency management of VBB.

The findings of this study can be used alongside the growing body of information on skill development and training on VBBs which until recently was scarce. Midwives and student midwives can use these findings to enhance educational opportunities within their institutions to increase individual and team competence and confidence. Three of the four participants identified as midwifery educators; therefore, this study has the unique perspective of pre-registration educators' experience, for all participants physiological breech birth was a new concept. While this is only a small study based in one area, these findings have the potential to affect student midwives' learning pathways and perceptions of VBB. A larger study of midwifery educator impact on pre-registration education delivery may ultimately influence midwifery workforce normalisation of VBB.

Strengths and limitations

A limitation of this study was the difficulty with recruitment and subsequent small sample size, due to COVID-19. Had there been more interest, two focus groups may have been held to allow for further interpretation of themes. A larger sample size may have led to a wider range of roles (student midwives, clinical midwives etc) potentially making findings transferrable (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013). While saturation was not reached due to the sample size and one focus group discussion, data were used pragmatically given the situation and the findings present a starting point for further studies. Furthermore, the focus group was held via a video conferencing call, potentially affecting participant involvement due to internet connections and ability to interject. Women's voices and choices were discussed by midwives and not women themselves which is a limitation for the true effect they have on VBBs. Future research may be able to focus on women's views of VBB and what they want practitioners to provide.

The lead researcher was the moderator for the focus group and posed semi-structured, open-ended questions allowing for more depth to be explored. Following data analysis, discussions took place with the research supervisor to ensure thoroughness and appropriate coding which enhanced inter-rater reliability and trustworthiness of findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Barbour, 2001). The lead researcher also kept a reflexivity diary which was used throughout the analysis process to prevent personal bias in the findings as it addressed personal values and interests which enhanced the creditability and confirmability of the findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Nowell et al, 2017).

Conclusion

This study adds to existing knowledge by highlighting that the barriers and facilitators to VBB skill attainment range from individual to organisational factors. The findings represent a continuum of change for influencing factors for skill attainment starting 20 years ago after the TBT, through to the contemporary practices and training in 2020. There was a shift from practitioners feeling they were ‘not in a good place’ and moving towards a ‘new normal’ of skill advancement. Changing the tide is a positive influence for VBBs, as midwives acknowledged a shift is happening because of the work of champions, midwifery leaders and respect for the woman's voice.

Key points

- Perceived competence by midwives in vaginal breech birth (VBB) is influenced by initial framing, mentorship, and personal experiences

- The theme of ‘not a good place’ acts as a driver for change in VBB skill acquisition as midwives felt a negative impact from the Term Breech Trial

- Champions and clinical midwifery leaders are advocates and facilitators for VBB education

- Continuity of carer models have the potential to provide for women's choices for a VBB and upskill midwives within the team

- Pre-registration curriculum changes may occur to encompass the normalisation of physiology of a VBB and initial framing to student midwives

CPD reflective questions

- Thinking about the ‘continuum of change’, where do you find yourself or your organisation on the continuum?

- What actions can/will you take to improve competence for yourself and/or others?

- Thinking about the options given to women who present with breech presentation, how do you feel these can be enhanced safely?

- What are your thoughts on the normalisation of breech birth physiology in the pre-registration curriculum?