Women with a raised body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 have an increased risk of pregnancy-related complications and adverse outcomes (Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries, 2010). For most adults, the stated ideal BMI is in the 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 range; between 25–29.9 kg/m2 a person is in the ‘overweight’ range; and at 30 kg/m2 and above, the individual falls into the ‘obese’ range. For the purposes of this study, a raised BMI was defined as 30 kg/m2 and above.

There is an expectation that midwives and other health professionals will discuss the risks of raised BMI with pregnant women and give diet and exercise advice, as per National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (NICE, 2010). However, there is evidence that midwives find the discussion of weight, diet and exercise difficult (Stotland et al, 2010; Schmied et al, 2011; Knight-Agarwal et al, 2014). This finding is mirrored in the experiences of pregnant women, who have reported feeling humiliated and stigmatised (Furber and McGowan, 2011), with negative emotions heightened through interactions with health professionals (Nyman et al, 2010).

There is concern that health professionals lack the skills and knowledge in how to communicate with obese women about their weight (Schmied et al, 2011; Heslehurst et al, 2014). These studies also show that, in discussions, health professionals are concerned about balancing the risks of obesity and the psychological impact on the women. One of the findings of a British study (Smith et al, 2012) was that health professionals found the discussion about raised BMI a ‘conversation stopper’, due to its sensitivity.

In this study, the experiences of a small British cohort of pregnant women with a raised BMI were explored to investigate if their pregnancies were affected by their interactions with midwives and other health professionals.

The aims of the study were to explore the perceived impact of interactions with health professionals, and to investigate participants' understanding of raised BMI and raised risk.

Methods

An exploratory qualitative approach was taken as this was considered the most appropriate method to explore individual's experiences. A purposive sample of participants (n=11) was recruited. The inclusion criteria were that participants should have a raised BMI (30 kg/m2 or more), and be pregnant at the time of study recruitment. The only exclusion criterion was if a woman did not have a good understanding of English. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews.

Recruitment

All the women were recruited from a hospital in the south-west of England. Women were screened by the clinical team when they attended an antenatal appointment. Eligible women were approached by the midwife researcher, who discussed the study with them and gave them a participant information sheet if they were interested in taking part. Women who expressed an interest were contacted by the midwife researcher by phone at a later date, to allow them time to consider the study. Of 31 women who were approached, 11 took part in the study. Of those who did not, 3 women declined at the time, 3 who were contacted by phone said they were too busy, and 1 had undergone a termination due to fetal abnormalities. The remaining 13 were unable to be contacted by phone.

Data collection

Data collection took place between January and June 2016. A total of 9 women were interviewed individually and a group interview was conducted with two participants. All individual interviews took place in the woman's home. The group interview took place in a meeting room on the hospital site, which was preferred by the participants. The interviews were all conducted by the same midwife researcher.

An interview framework was developed following a review of the literature and discussion with clinical colleagues (Table 1). As the interviews progressed, and areas of interest to the women were discussed, additional questions were introduced in response to thoughts and comments by previous participants, such as the impact of the scan.

| Are you aware of any guidelines concerning women's weight and pregnancy/birth? |

| Has your midwife or doctor talked to you about your weight, diet and exercise, or about any additional care/tests you might have? |

| How have you felt when your weight has been discussed? What language or words do you like/dislike? |

| What would you like to hear from midwives? |

Written consent was obtained from all women before being interviewed. Interviews lasted between 9 and 42 minutes, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each interview was listened to shortly after completion and notes taken as an aide mémoire and also as an early start to the analysis. Data saturation was considered at the point when nothing new was apparent from the interviews. At this point, no further women were recruited to the study.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used, following the steps detailed by Braun and Clarke (2006) to ensure the analysis was theoretically and methodologically sound. An inductive approach was taken to the analysis and a coding frame was developed systematically, following the manual coding of the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The codes emerged from reading and re-reading of the transcripts, which were grouped into sub-themes and then final themes. A selection of the transcripts was independently coded by an experienced co-investigator to establish inter-coder agreement. A third member of the team was also involved in the development of the themes to provide additional rigour to the findings. The themes were also discussed with clinical midwives to get feedback on their clarity and sense.

The study received approval from the local Research Ethics Committee (NRES Committee South West) Cornwall and Plymouth (reference 15/SW/0075).

Findings

Overall, 3 women were primiparous and 8 were multiparous. All were in their third trimester of pregnancy. Participants were aged between 19–38 and were all white British, with BMIs that ranged from 31.2–47.3 kg/m².

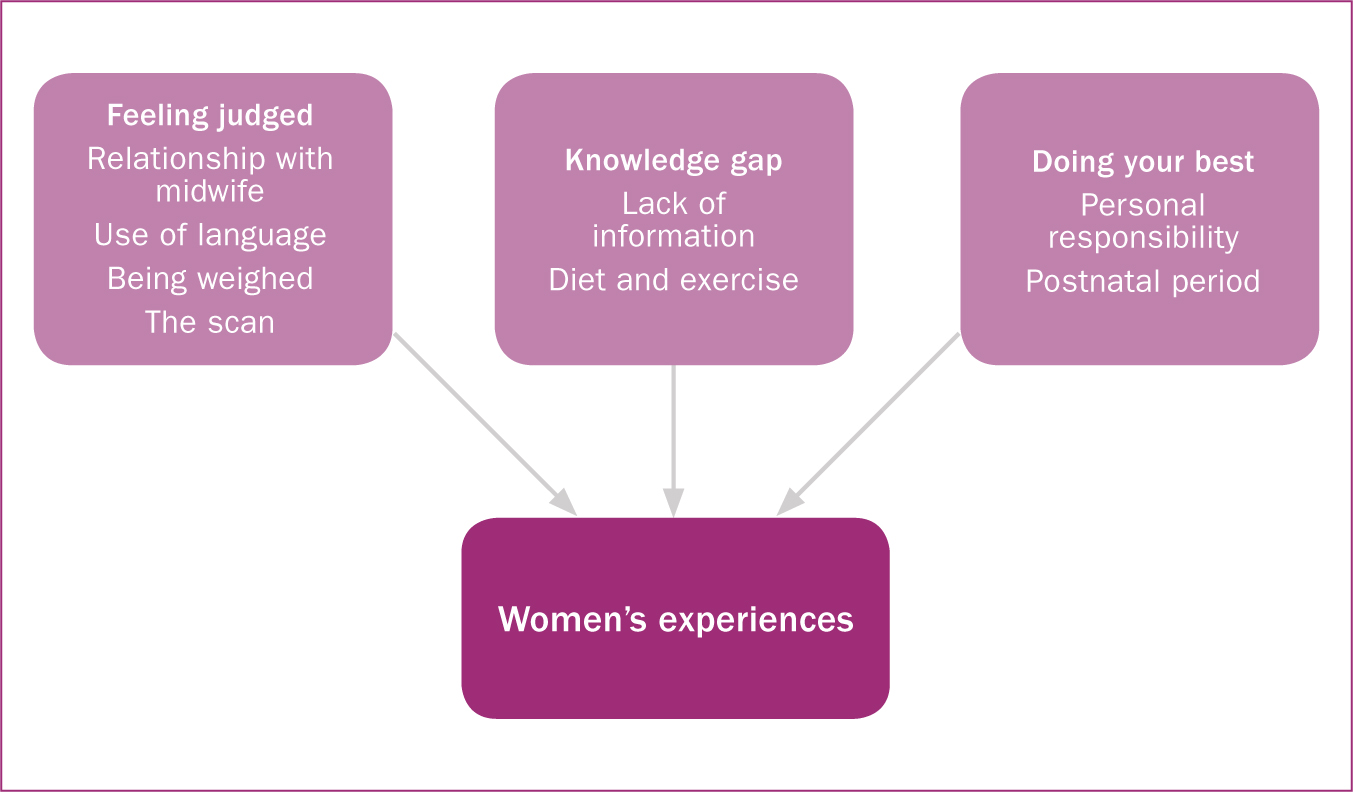

Three themes emerged from the data: ‘feeling judged’; ‘knowledge gap’ and ‘doing your best’. Themes and sub-themes are presented in Figure 1.

Feeling judged

Participants had concerns that they were being judged because of their weight. The sub-themes related to interaction between the participants and midwives (‘relationship with midwife’ and ‘acceptable language’) and key events in the pregnancy journey (‘being weighed’ and ‘the scan’).

Guilt and embarrassment

Some participants expressed embarrassment about having extra tests and others expressed guilt about their raised BMI. Some spoke about their raised BMI in terms of ‘other people’ who were upset and sensitive about their weight (Participants 1 and 6), while others, such as Participants 10 and 11 were able to identify these feelings about themselves:

‘You just feel, I guess, a bit guilty because you put yourself at this risk.’

‘I think there is an element that probably for most people, their status as a pregnant woman with a raised BMI is, to a certain extent, sort of self-inflicted and, you know, the needing of additional care as simply as a result of that does, yeah, definitely made me feel guilty.’

Relationship with midwife

Most participants appeared to have a good relationship with their midwives and stressed the support they had had during their pregnancy. However, one participant (Participant 2) found the attitude of her midwife to her weight to be unhelpful and upsetting. A small number of women (Participants 3 and 6) felt that their midwife had been embarrassed to address their weight and they felt the midwife had found the conversation difficult.

‘I think she just found it a little bit awkward and didn't really feel like talking about it, but then again I didn't ask questions about it either.’

Others had found their midwife to be honest and professional about their weight and had presented it in a factual and non-judgemental way, as Participant 8 explained:

‘I never felt labelled as a pregnant lady with a raised BMI, it was always just a “well, this is what the science shows.”’

Some could foresee the potential of being judged and had a fear that midwives might be unsympathetic and insensitive, such as Participant 1, who said:

‘You know the last thing you want is, um, to be given a lecture or anything like that.’

Some women appeared to be hyper-aware of how suggestions or recommendations from midwives (for example, regarding diet and exercise) may be misconstrued as criticism. One participant said she was made to feel that she was not doing the best for her baby (due to her raised BMI) and gave the example of what might be said by a midwife:

‘“Oh well, you didn't lose weight before you fell pregnant” or “you're not trying to lose weight now, so you don't care about your baby.”’

However there was recognition that the discussions about weight were a necessary part of midwifery care:

‘I feel like I have had excellent care and that nothing that has happened to me or, you know, nothing about the way I have been treated, has made me feel like there is any judgement. I am probably my own harshest critic, as I imagine most women probably are.’

Acceptable language

The word ‘obese’ was considered unacceptable. Women described it as ‘personal’ (Participant 7), and ‘degrading’ (Participant 2), and one stated ‘I don't think that's a nice word to use' (Participant 4). Only one woman (Participant 11) stated that obese was acceptable as it was a factual word.

The majority of women did not perceive themselves as obese. One (Participant 8) described obese people as ‘massive, massive people’ and most explained that although it might factually describe them, they did not feel that the word was appropriate to them.

‘I see somebody that's obese as somebody that doesn't care about their weight, in a way … And when you, when I hear the word obese, I have seen obese people and I don't look like obese people.’

All participants stated that ‘raised BMI’ was an acceptable, factual term and one that was understandable to them. The women said that health professionals had used ‘raised BMI’ when discussing their weight rather than the word ‘obese’.

‘I think it's a good term because [BMI is] a medical term and, um, it's less emotive than, um, ‘obesity’ or, you know, even ‘weight’. You know some people, you know, get a bit upset if increased weight is talked about, especially if they are pregnant. Emotions are running high anyway. Er, so yes, I think it's a good enough term.’

Being weighed

The majority of the participants had a long history of dieting and trying to control their weight. Many had been in diet clubs and were very body conscious.

‘Weight has always been a huge thing for me, throughout my whole life … I would love to be skinny, I would love to be thin, but it's hard.’

Most participants were used to being weighed, but many also spoke of regular self-weighing. Participant 11 recalled that it was a ‘factual’ exercise that did not give her too much concern, while another (Participant 2) said that she ‘hated it’. One woman (Participant 10) had anticipated being weighed and explained she was worried about attending the antenatal clinic for this reason. As a result, she had delayed contacting her midwife.

‘It's always embarrassing to stand on the scales, yeah, it was difficult, to be overweight before you've even, you know, started but it wasn't an issue at all from her [the midwife], it's more me.’

The scan

The scan was a particular time of concern for some participants and communication about visibility of the baby caused some upset and confusion:

‘On my scan notes, um, even though they have, um, a perfect view [of the baby] and managed to see everything, they still put on your notes “restricted view due to raised BMI.”’

Some felt it was a tick-box exercise (Participant 10) or one of ‘covering their backs' (Participant 1), rather than a clinical response to the difficulty of the scan.

Knowledge gap

This theme developed from the way the participants described their interactions with midwives, and their participation in the additional tests required due to raised BMI. Overall, the women reported a lack of information about their raised BMI.

Lack of information

‘I think you do need to know [about raised BMI], and it can't be sugar-coated.’

The majority of participants did not remember their midwives talking in any detail about their raised BMI, nor why it might be important for them to know this information.

‘I got told that I had raised BMI, um, and then that's as far as it went. So I haven't been told that you can have complications during your pregnancy, or your labour.’

However, Participant 8 recalled a good discussion with her midwife about the risks associated with her raised BMI and felt well informed. Participant 2 could also remember information about risks but she also felt that she had been given inconsistent advice, which left her feeling confused and uncertain about the importance of raised BMI:

‘I have been told various different things and basically that everything can be complicated by the BMI […] but also nothing can be complicated by raised BMI.’

Written information was familiar to some women but not others. One participant (Participant 6) said that her midwife gave her lots of paperwork (‘She just threw everything at me’) because she had had complications in her last pregnancy. Another (Participant 4) said that nothing had been explained to her. Participant 3 found the written care pathway for women with a raised BMI useful as a way of knowing what appointments she had ahead of her. However, she too explained that she was not given reasons for the additional appointments.

Most of the women were referred to a consultant due to their raised BMI and obstetric factors, such as previous caesarean section. There was confusion in the reasons for referral and the women explained the consultant involvement largely due to other factors unrelated to their weight.

‘Because I am under consultant care, I have been told by one midwife that it's because of my BMI mainly, whereas the other midwife I have been seeing recently said no, it's to do with my daughter's birth weight.’

Some women felt they would like information on how much weight they could safely gain in pregnancy:

‘There has not been any discussion. There has been no discussion at all about my weight, um, whether being overweight, or you know, the amount of weight I have put on in pregnancy there hasn't been any, no discussion about it at all.’

Diet and exercise

Some women expressed a desire for more information. Discussion about the women's diets were mostly confined to what was best omitted in the diet in pregnancy to protect the baby. However, more information would have been helpful to some women:

‘I think it would be nice, um, again to talk about diet or them to ask you what you are eating or what you should be doing (should you be doing exercise) or asking you, and maybe it should be a question of “Do you exercise?” or “What do you do, what do you eat?”’

There was also a lack of information about exercising in pregnancy. Three of the women suffered from pelvic girdle pain and were restricted in their daily activities. One, who said she was usually active, explained that she did not feel like doing much exercise towards the end of the pregnancy. Only three women (Participants 6, 8 and 10) spoke about exercising as important in pregnancy.

‘I think definitely exercise is important, because not only would it benefit you, you know physically, um, it gives stress relief and also there is everything about keeping active makes labour easier.’

Doing your best

There was a desire by participants to do the best they could to ensure a healthy pregnancy. They expressed this by following guidelines, being aware of their eating habits and attending appointments.

The participants appeared happy to follow the recommendations of the midwives, despite not having a full understanding of the reasons:

‘Were reasons given? No, not particularly. I just did it [the oral glucose tolerance test]; to be honest, I didn't really question it. No, I don't really know why.’

Personal responsibility

There was clearly a desire by all participants to manage their weight and eat healthily. They spoke about watching what they ate and many had a clear idea about how their behaviour could influence their weight gain:

‘This time I have been a lot more sensible. I think I have kind of realised that I don't want to put the weight on again, because it's harder as you get older to actually to get rid of the weight, so I think I have been a bit more sensible this time.’

Rarer still was the proactive attitude of Participant 6, who was on her second pregnancy and wanted to make a difference to her blood pressure:

‘Your blood pressure is an increased risk with increased weight so I was trying to walk a lot. I am just trying to reduce my blood pressure as much as possible.’

Postnatal period

Some women had plans to be proactive over weight loss in the postnatal period; it appeared pregnancy was a hiatus in their efforts to manage their weight, which, for some, was frustrating. The women looked forward to the time after pregnancy and spoke of plans to lose weight:

‘I have always been on diets and things, um, I have already got my plan and I am going back to Slimming World.’

Discussion

This study gives an insight into the experiences of women with a raised BMI and their communication with health professionals. Some women in this study felt judged and criticised by health professionals as has been found in other studies (Furber and McGowan, 2011; Smith and Lavender, 2011). Most women were acutely aware of their raised BMI and sensitive to the words and actions of the health professionals whom they saw, which is confirmed by findings from other studies (Mills et al, 2013; Nyman et al, 2010). Women with a raised BMI have been shown to have low levels of self-worth and to feel guilty (Lindhardt et al, 2015; Nyman et al, 2010). This was displayed by some of the participants in this study.

Participants reported that the terminology used by midwives was consistent and that ‘raised BMI’ was considered acceptable and appropriate by participants, while ‘obese’ was found to be rude and offensive. This is supported by findings from other studies (Gray et al, 2011; Volger et al, 2012; Atkinson and McNamara, 2017). Other studies, however, have criticised the use of BMI as a euphemism and a technical term (Mills et al, 2013; Schmied et al, 2011). Moreover, women in this study did not consider themselves obese, which has implications for using this term in healthcare.

The findings demonstrate that the women interviewed lacked knowledge about raised BMI and risk, as well as the reasons for additional interventions; this is supported by the findings of earlier studies (Keely et al, 2011; Shub et al, 2013; Heslehurst, 2014; Knight-Agarwal, 2016). This gap in knowledge could be explained by midwives not communicating this information (due to time pressures, level of knowledge, or embarrassment); the women forgetting the discussions; or a combination of both. There is evidence to suggest that midwives lack skills and confidence to support women with a raised BMI (Stotland et al, 2010; Furness et al, 2011; Schmied et al, 2011; Smith et al, 2012), which can express itself as embarrassment. A systematic review (Heslehurst et al, 2014) found evidence that midwives lacked training and experienced difficulties in communicating with women about raised BMI.

Previous studies have reported that participants often did not have a discussion with a midwife about weight and lifestyle, despite being ready to make changes (Lavender and Smith, 2016). In a separate study, women knew that it was important to eat well and be physically active but lacked the ‘practical application of this knowledge’, while support from midwives was limited (de Jersey et al, 2013:120). Another study (McParlin et al, 2017) found that midwives understood physical activity to be an important part of their job but lacked the skills and resources to discuss physical activity and did not prioritise these discussions. Recommendation 6 of the NICE guideline ‘Weight management before, during and after pregnancy’ (NICE, 2010) highlights the need for training in communication techniques to help health professionals broach the subject of weight in a sensitive manner; however, the findings of this study, along with those of earlier studies, demonstrate that this has not yet been addressed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A limitation of the study is that the participants were all white British and from a single hospital Trust, which may reduce the transferability of the findings to other settings. The researcher who conducted the interviews could have influenced the participants due to a power imbalance between interviewer and interviewee; however, the researcher was not at any time responsible for the participants' care, and any perceived imbalance was intended to be mitigated by conducting interviews in participants' homes. This study was undertaken as a result of the interests of the researcher and her experiences as a midwife may influence the findings.

Conclusions

This study has shown that pregnant women with a raised BMI feel judged in their communications with midwives and other health professionals. They do not have the information necessary to make informed decisions on their care but they do their best to follow guidelines and have a healthy pregnancy.