In many countries, pregnant women experience an increasing range of testing and monitoring procedures. Early identification of risk factors can facilitate appropriate triaging to specialist clinics with concentrated expertise, for example to address hypertension, fetal growth issues, multiple pregnancy, and risk of preterm birth. These clinics can improve the prediction, prevention and treatment of pregnancy complications but they could also increase anxiety. For example, a study reported that fetal fibronectin testing predicted preterm delivery in high-risk women but the procedure also raised anxiety (Shennan et al, 2005).

A first recorded investigation of pregnancy and birth-related psychological distress was carried out in 1956 when 50 pregnant women were asked to report on areas that they had felt anxious about during pregnancy and the postpartum period (Pleshette et al, 1956). Amidst a range of concerns, women reported worrying about fetal abnormalities and stillbirth. A recent review suggests that the number of studies reporting perinatal anxiety has grown and with wide variations in prevalence estimates (2.6–39%) (Leach et al, 2017). Qualitative research has further identified psychological distress associated with specific perinatal risks such as preterm birth (O'Brien et al, 2017). The offer of appropriate reassurances and education or triaging to psychological care is dependent on consistent recognition of anxiety and worries in an environment characterised by the high volume of clinical throughout. How can maternity staff consistently detect pregnancy related anxiety without burdening service users?

In many healthcare settings, screening tools have been developed to enable clinicians to methodically identify patient distress. The deployment of such tools has been found to increase treatment compliance, improve patient experience and reduce healthcare costs (Velikova et al, 2004; Bultz and Carlson, 2005). Brief screening tools are intended for routine use by generic care providers; they are not the same as detailed psychological assessments carried out by mental health professionals. The current study was the first step to develop a user-friendly measure of perinatal anxiety and to find out what concerned women the most. The longer-term objective was to improve capacity for addressing the anxiety of attendees at preterm and other high-risk antenatal clinics. In particular, we wanted to find out whether it was feasible to use a tool already in routine use in other healthcare settings.

Emotion thermometers

The ‘distress thermometer’ (DT) is a single visual analogue measure pictorially represented as a vertical temperature thermometer, along which the patient gives a distress rating from 0–10. Next to the scale is a list of problems in several domains specific to the clinical condition (eg under a domain labelled ‘physical symptoms’, the list may include items such as ‘nausea’ or ‘fatigue’). The DT is brief, easy to use and provides a focal point for the consultation whereby clinicians can ask patients about their psychological well-being.

Originally validated in the US (Roth et al, 1998; Jacobsen et al, 2005), it was subsequently validated for cancer services in a number of other countries (Gil et al, 2005; Gessler et al, 2008; Grassi et al, 2013) and tried and tested extensively. A meta-analysis concluded that the DT was a valid first-stage screening tool for cancer patients (Mitchell, 2007). Although much less extensively researched in non-cancer settings, the DT has been applied to some chronic illness settings including paediatric services where it has been used with children (Kazak et al, 2012) and parents of children with chronic health problems (Haverman et al, 2013).

In response to criticisms about the ambiguous meaning of the term distress, which can be difficult to translate into some languages, emotion-specific thermometers have been developed, such as the anxiety ther mometer (AnxT) and depression thermometer (DepT) which have been examined in oncology (Mitchell et al, 2010a; 2010b). Since then, these emotion thermometers have also been piloted in cardiology (Mitchell et al, 2012) where the AnxT was found to perform well against the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al, 2006). None of these ultra-brief tools have been examined in maternity settings.

The aim of current study was to find out how feasible it was to adapt the AnxT (Mitchell et al, 2010a; 2010b; 2012) for use with antenatal cohorts. Although the long-term objective was to develop the tool to track anxiety and concerns of women attending high-risk clinics through to the postnatal period, at this exploratory stage, we included women attending high- and low-risk antenatal clinics in a single time point.

Materials and methods

The study took place at a large maternity unit in a teaching hospital in London, UK.

Impact statement

| What is already known on this subject? Research shows that pregnancy and potential and actual pregnancy complications are associated with anxiety for some women. Anxiety measures exist but they are too long for repeat use during antenatal visits |

| What do the results of this study add? Participation rate of an adapted version of the anxiety thermometer (AnxT), an ultra-brief tool developed in other healthcare settings for repeat use was almost 100% in the antenatal clinics involved in the current feasibility study |

| What the implications are of these findings for clinical practice and/or further research? The current feasibility study introduces into maternity care for the first time the AnxT, an ultra-brief tool established for in other healthcare settings. The tool was refined and renamed the perinatal AnxT which is ready to be tested across maternity units |

Participants

Pregnant women attending low-risk antenatal clinics, the specialist preterm clinic and the multiple pregnancy clinic were approached by a midwife (YR) as they waited for their antenatal appointments. Women were provided with an information leaflet regarding the study and a consent form. Referral criteria to the preterm birth clinic include a history of at least one spontaneous late miscarriage or preterm birth, cone biopsy or at least one large loop excision of the transformation zone. Women attending the multiple pregnancy clinics carry twin or higher order multiple gestations. Of the participants, 67 (66.7%) were in their second trimester, 28 (27.7%) in their third trimester and six (5.9%) in their first trimester.

Measure

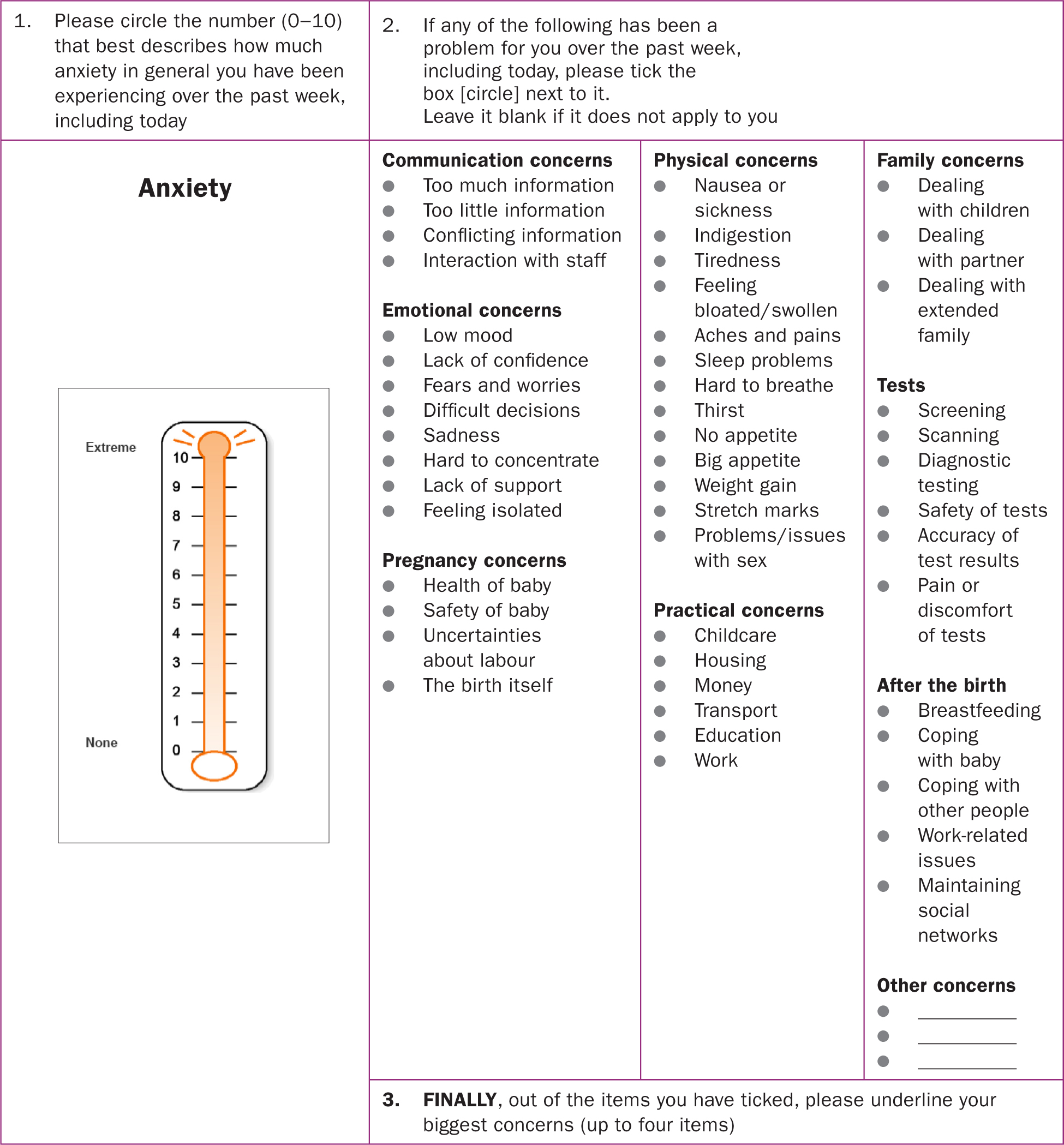

The AnxT is a single page, pen and paper assessment which takes less than one minute to complete, as presented in Figure 1. Women were asked on the paper, ‘How anxious have you been during the past week on a scale of 0–10?’ They put a mark along a vertical thermometer with 0 at the bottom (labeled ‘NONE’) and 10 at the top (labelled ‘EXTREME’).

Figure 1. Anxiety thermometer version used in current feasibility study

Figure 1. Anxiety thermometer version used in current feasibility study

Next to the pictorial thermometer is a checklist of concerns. In a meta-analysis of research with other clinical cohorts, scores of four or above on the original DT was found to be predictive of reporting one or more problems on every domain of the checklist (Mitchell, 2007). The problem checklist was re-developed for the current study with pregnant women, based on the concerns and worries commonly reported to the authors. The checklist included the following domains: communication concerns, emotional concerns, pregnancy concerns, physical concerns, practical concerns, practical concerns, family concerns, birth and after the birth. Participants were asked to tick any of the concerns listed under the domains that applied to them in the preceding week. They were also asked to underline their biggest concerns.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24 (Chicago, US). Pearson's r-correlation coefficient was performed to identify associations between continuous variables and an independent t-test to identify potential differences between groups. P-values of less than 5% was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The questionnaire was distributed to 102 women and was completed by 101 respondents. The median maternal age was 34.5 years (SD=4.7) ranging from 22–44 years. Mean gestation was 23 weeks (SD=7.7) ranging from 10–39 weeks. For 50 women (49.5%), this was their first pregnancy; 34 (33.7%) women had one living child, six (5.9%) had two living children and two (2%) had four children. Of the women, 18 (17.8%) had had one miscarriage, two (2%) had two miscarriages and one (1%) had four miscarriages.

Scores on the AnxT ranged between 0–10 with a mean anxiety score of 4.7 (SD=2.6). Of the women, 38 scored below four but 63/101 scored four or above, with 15 of these women scoring between 8–10.

There were no significant associations between AnxT scores and age, weeks of gestation, number of miscarriages and number of living children. Independent t-tests did not identify any significant difference in AnxT scores between women aged 35 years or more and women aged under 35 years, and between women who had had one or more previous miscarriage(s) and those who had not. Frequencies of reported concerns are presented in Table 1. Health of baby was the most frequently reported concern followed by tiredness, fears and worries, and sleep problems. Health of baby was also most frequently reported as the biggest concern. About a third reported concerns about work with 10% naming work as the biggest concern. Testing, communication and family appeared to be the least problematic domains.

Table 1. Prevalence of problems and biggest concerns (N=101)

| Domains and concerns | Current problem | Biggest concern | Biggest concern | Current problem | Biggest concern | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Communication | Practical concerns | ||||||||

|

71388 | 6.912.97.97.9 | -222 | -2.02.02.0 |

|

199255634 | 18.88.924.85.05.933.7 | 3131310 | 3.01.03.01.03.09.9 |

| Emotional concerns | Family concerns | ||||||||

|

95507101722 | 8.95.049.56.99.916.82.02.0 | 1125-131- | 1.01.024.8-1.03.01.0- |

|

9 5 12 | 8.9 5.0 11.0 | 3 2 4 | 3.0 2.0 4.0 |

| Pregnancy concerns | Tests | ||||||||

|

62343636 | 61.433.735.635.6 | 43191514 | 42.618.814.913.9 |

|

71076126 | 6.99.96.95.911.95.9 | 242231 | 2.04.02.02.03.01.0 |

| Physical concerns | After the birth | ||||||||

|

161650144147139771771 | 15.815.849.513.940.646.512.98.96.96.916.86.91.0 | 42145810-11141- | 4.02.013.95.07.99.0-1.01.01.04.01.0- |

|

20168171 | 19.815.87.916.81.0 | 6613- | 5.95.91.03.0- |

| Other concerns | |||||||||

| Hard to contact ACN Disabled baby My safety Preterm labour | 1111 | 1.01.01.01.0 | --1- | --1.0- | Food does not taste the same After birth concerns Constipation | 111 | 1.01.01.0 | --- | --- |

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to find out how feasible it was to use the AnxT with maternity service users. Only one woman declined to participate, reasons for non-participation was not questioned. All other respondents were keen to complete the tool. The midwife YR was not present when women completed the AnxT. The completed form was given to the receptionist. Close to two-thirds of the participants scored four or above with a sizeable minority scoring eight or above, suggesting a need for future research to identify factors that contribute to higher anxiety levels.

The small sample size did not permit any detailed analysis of potential effects of demographic or clinical factors which in any case was not the study objective. Perhaps predictably, women were most likely to report being concerned about fetal health. Some physical and emotional symptoms, particularly tiredness, sleep problems, and fears and worries, appeared to affect a relatively high proportion of women. Work as an area of difficulty is rarely attended to in perinatal psychological research. It has emerged as a potential source of anxiety for women.

The reason for refining the AnxT was to enable maternity staff to routinely screen for perinatal anxiety so to facilitate conversation, offer education and reassurance, and triage to psychological services for more detailed assessments or interventions as appropriate. However, future studies are needed to address a number of questions before the AnxT could be confidently adopted for routine use.

Research with other clinical populations has found the AnxT to perform well against more detailed psychological assessments of anxiety (Mitchell et al, 2010a; 2010b; 2012). Nevertheless, validation work should be replicated with perinatal populations. Scores on the AnxT could, for example, be compared to those on more detailed measures of perinatal anxiety such as the 31-item perinatal anxiety screening scale (Somerville et al, 2014) and general anxiety measures such as the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al, 2006). In the current study, first-time antenatal clinic attendees and postnatal women were excluded.

Further work would need to establish whether the AnxT is equally acceptable to these groups. Larger samples recruited in multi-centres would enable us to assess any differences between socio-demographic and clinical cohorts. Repeat assessments along the perinatal journey would enable maternity staff to track anxiety and concerns from pre- to postnatal to learn about women's anxiety and offer appropriate support. This would mean research to establish compliance with multiple testing. As and when the AnxT is ready to be rolled out as part of a structured programme to enhance maternity care, it would be important to evaluate impact on care user satisfaction.

In the current feasibility study, a midwife was present to ensure that all eligible women were invited to complete the AnxT. This would be a costly procedure as a requirement for implementation. If antenatal clinic staff were to be trained to administer and discuss results of the AnxT during routine consultation, fidelity research is required to assess the impact without a designated person in clinic to ensure consistency.

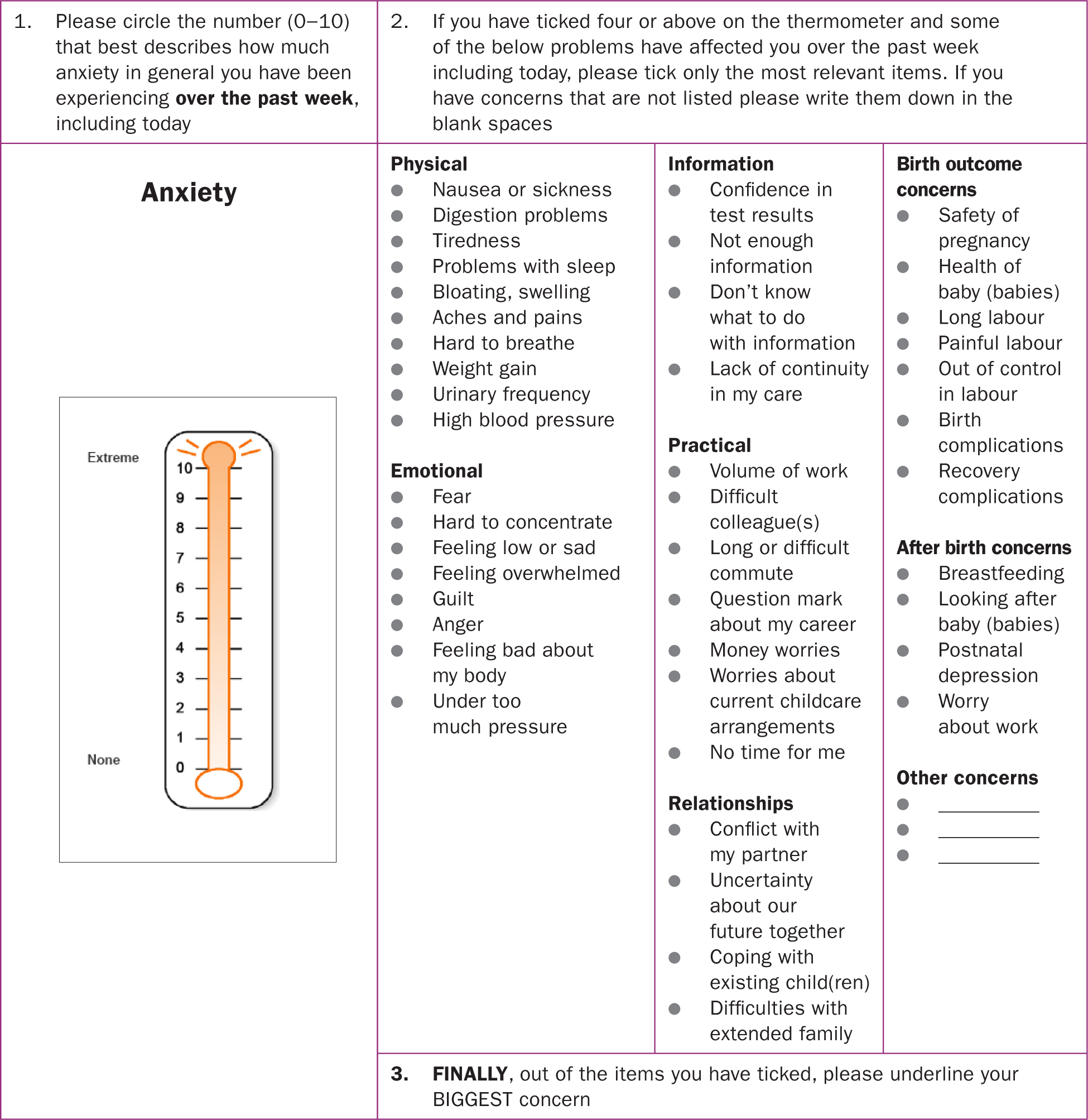

Based on the current findings, the least frequently checked items on the problem page of the current pilot version of the AnxT (Figure 1) were removed. Descriptions of some of the items were improved for clarification. A few new items are added. Work-related problems are expanded to elicit more information about pregnant women's struggles with work because a third of the current sample have reported this to be an area of anxiety for them and 10% reported this as their biggest concern. In the enhanced version, which we call perinatal AnxT, presented in Figure 2, participants are asked to underline only one of their biggest concerns (as opposed to four in the version being piloted). This improved tool could be the focus of future research to develop a brief screening tool that can be repeated throughout the perinatal journey.

Figure 2. Perinatal anxiety thermometer version refined for further research

Figure 2. Perinatal anxiety thermometer version refined for further research

Conclusions

This was the first step towards developing the AnxT to screen for anxiety and elicit perinatal concerns of pregnant women attending follow-up appointments. The results suggest that the ultra-brief screening tool is feasible and acceptable. The participants' responses to the problem checklist provided useful information to streamline the checklist somewhat. The resultant, refined version (perinatal AnxT) warrants further research which could potentially lead to broad implementation with antenatal and postnatal care users.

Key points

- Perinatal anxiety is increasingly recognised as a clinical care in maternity, midwives and healthcare professionals need screening tools to identify women

- Failure to identify women in the antenatal period may lead them to feeling isolated and unsupported, and may impact on their psychological health and health of their baby

- Brief screening tools to assess anxiety during pregnancy are feasible and acceptable to women during the antenatal period