Providing high-quality midwifery services is one of the most important strategies for improving maternal health. Research has shown that midwives have an important role in providing cost-effective maternal-neonatal care (Renfrew et al, 2014). The factors affecting midwives' decision to continue providing midwifery services or leave their job include having a desirable professional quality of life, feeling supported by their managers, having access to sufficient resources and experiencing a sense of empowerment and control over their work (Sullivan et al, 2011).

Professional quality of life is a multidimensional concept that is influenced by personnel's perception of their work and satisfaction with resources and activities in the workplace (Hesam et al, 2012; Zarei et al, 2016). This concept is the result of an organisation's employees' perception of the psychological and physical conditions of their workplace and their attitude toward their professional life. Professional quality of life involves the concepts of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue (Stamm, 2010). Compassion satisfaction means feeling happy about caring for others and includes the emergence of positive aspects and a feeling of happiness that make a person enjoy helping others when performing their professional duties (Stamm, 2005). Meanwhile, compassion fatigue is caused by occupational hazards in people who frequently witness other people's suffering, pain and physical and psychological harm and is referred to as the ‘cost of medical care’ (Bush, 2009; Matthews et al, 2009). Burnout is a long-term response to occupational stressors in a non-supportive organisational atmosphere that leads to physical, mental and emotional fatigue. Secondary traumatic stress refers to sudden signs in healthcare providers following the incidence of a traumatic event for a patient, such as sadness, anger, despair, feeling futile, apathy towards the profession, reduced profitability and nightmares.

The results of a cross-sectional study in Greece investigating the prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue showed that most (73.9%) nurses and midwives working in obstetrics and gynaecology wards were at high risk of compassion fatigue in the dimension of secondary traumatic stress and only 19.8% had high compassion satisfaction (Katsantoni et al, 2019). The results of a study conducted in Iran on 464 healthcare providers, including physicians, midwives and nurses, showed that participants had a moderate professional quality of life, and factors such as job satisfaction, income and work shift schedule were its predictors (Keshavarz et al, 2019). Midwives' professional quality of life varies in different societies according to background, workplace structure and organisational culture in the workplace.

Today, a main goal of health organisations is to improve professional quality of life, as addressing factors affecting personnel's professional quality of life helps improve the productivity of the organisation (Saber et al, 2013). Personnel with higher professional quality of life have stronger organisational identity, greater job satisfaction, better performance and greater organisational commitment (Hesam et al, 2012). Dissatisfaction with professional quality of life can lead to a loss of motivation, increased absenteeism, mental distress and resignation from work (Mehdad et al, 2011). In a compassionate organisational culture, proper clinical supervision and ongoing training can protect healthcare workers against absorption or internalisation of feelings that lead to compassion fatigue and also help them have a deeper understanding of their communication and interactions during highly charged moments (Katsantoni et al, 2019).

In the midwifery profession, the factors affecting a midwife's professional quality of life include feeling supported by their managers, access to sufficient resources, establishing good relations with the parturient, experiencing a sense of empowerment and the degree of control over decision-making (Sullivan et al, 2011).

In the context of professional quality of life, empowerment means designing the structure of an organisation in a way that prepares individuals to accept more responsibilities while exercising control over themselves (Sheikhpoor and Sheikhpoor, 2015). Empowerment is a process by which a manager helps personnel gather the power needed to independently make decisions, which not only affects their performance but also their personality (Lawler, 1994). However, the concept of empowerment is different in the context of midwifery because of the unique aspects of this profession, including autonomous practice. An important part of midwifery care involves the empowerment of women and their families to control the factors affecting their health (Fahy, 2002). If a midwife is meant to empower women, she should first experience her own empowerment (Kirkham, 1999). Today, many midwives increasingly feel that their professional skills have been adopted by other members of the medical team (Hadjigeorgiou and Coxon, 2014), which potentially causes a perception of less professional empowerment in midwives and affects their professional quality of life.

Midwives' definition and perception of empowerment vary depending on the culture, social context and theoretical approach applied (Kennedy et al, 2015). In studies conducted in Turkey, midwives had a moderate perception of empowerment in the dimensions of management, advocacy and resources and a high perception of empowerment in the dimension of professional skills (Murat Öztürk et al, 2018). In contrast, Norwegian midwives have a higher perception of empowerment in all dimensions (Lukasse and Pajalic, 2016), and this disparity is probably the result of the differences in the countries' education systems, management and health policy-making.

In the past, Iranian midwives independently provided perinatal care to pregnant women during pregnancy, labour, childbirth and post-delivery. In the past three decades, their role in managing low-risk pregnancy natural childbirth has diminished as a result of the medicalisation of low-risk pregnancy care (Pazandeh et al, 2015). In teaching hospitals, natural childbirths are managed by obstetrics/gynaecology residents. In non-teaching hospitals, natural childbirths are managed by midwives supervised by specialists, regardless of their academic degree or work experience, and extensive medical intervention is occasionally involved. Overall, midwives have little independence in controlling low-risk childbirths. Many women, even multiparous ones, now prefer to deliver at a hospital, and hospitals providing midwife-led services include only a few rural birth centers in which midwives manage low-risk childbirths. Results of a cross-sectional study in Iran showed that only 35% of childbirths were managed by midwives, while 65% were managed by obstetrics/gynaecology residents (Khodakarami and Jannesari, 2009). In recent years, 48% of all childbirths have been caesarean sections (Rafiei et al, 2018), a value that reaches 87% in some private hospitals (Azamui-Aghdash et al, 2014).

Following the 2014 Health Reform Plan in Iran, policies have been enacted to promote natural childbirth by offering incentives such as free natural childbirth, free preparation courses for pregnancy instructed by midwives in state-run centers and large-scale workshops on physiologic birth to empower midwives (Moradi-Lakeh and Vosoogh-Moghaddam, 2015). However, midwives face limitations in providing midwifery services, especially in natural birth care. The medicalisation of pregnancy and childbirth has marginalised Iranian midwives (Najmabadi et al, 2020). Strict rules and regulations and legal prosecution for medical negligence and errors made by midwives (even though they do not issue orders during labour and delivery) may also motivate midwives to leave the pregnancy and childbirth care system. Despite the status and potential of midwifery for professional development and growth, the existing professional rules and regulations of the Iranian healthcare system have restricted optimal exploitation of these potentials. The incompatibility between midwives' scientific and practical capabilities and their scope of responsibilities can negatively impact their perception of their professional competence.

Taking into account the factors affecting the professional quality of life creates a more humane work environment in which both the basic needs of personnel and their higher-level needs, such as the need for ongoing development and performance improvement, are considered (Tehranineshat et al, 2020). In recent years, the many dimensions of professional quality of life have been more seriously addressed because of the close relationship between the concept of professional quality of life and clinical-professional performance and clinical competency (Kim et al, 2015). Studies conducted in Iran on midwives' professional quality of life are limited and the experiences of midwives about their perception of empowerment in the workplace have been neglected. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the role of midwives' perception of empowerment in their professional quality of life. The results of this study emphasise the importance of planning to improve midwives' empowerment not only with respect to education but also in terms of professionalism, autonomous practice, management and advocacy, and can assist in improving professional quality of life in this group of healthcare workers.

Methods

The present descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted with the participation of midwives working in five provinces of Iran. The inclusion criteria were having an academic qualification in midwifery and a minimum of 1 year of work experience in prenatal care or labour and childbirth services. The exclusion criteria were working in any field other than maternal care.

Sampling

Purposive sampling was conducted electronically using virtual platforms through smartphones. The study population consisted of all midwives working in comprehensive health centers, hospitals and private midwifery surgeries in five provinces of Iran: west and east Azarbaijan, Isfahan, Alborz and Khuzestan. Based on the correlation sample size formula (Hulley et al, 2013), the sample size was estimated as at least 260 midwives. Assuming a 15% participation rate, as seen in similar online studies (Beck and Gable, 2012), the questionnaire link was given to 2000 midwives who were members of professional groups on social media.

Data collection

Data were collected using a personal-demographic questionnaire, the Professional Quality of Life Questionnaire and the Perception of Empowerment in Midwifery Scale. The Professional Quality of Life Questionnaire is a tool that measures positive and negative occupational influences on medical and healthcare personnel. The original version includes 30 items in three subscales: compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Hundall Stamm, 2009).

In the present study, the Persian version of this questionnaire was used, which has been validated by Ghorji et al (2018). In the factor analysis of the Persian version, five items were eliminated and 25 were placed in the three dimensions of compassion satisfaction (10 items), burnout (5 items), and secondary traumatic stress (10 items). Scoring was based on a five-point Likert scale from never (1 point) to very often (5 points). The internal consistency reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire has been confirmed with Cronbach's alpha of 0.73 (Ghorji et al, 2018). In the present study, the overall reliability of this questionnaire was confirmed with Cronbach's alpha of 0.7.

The original version of the Perception of Empowerment in Midwifery Scale has 22 items in three domains, including autonomous practice, effective management and women-centered practice (Matthews et al, 2009). The Persian version of this scale was used in this study, which was defined with 17 items in five domains based on an exploratory factor analysis: effective management, professional practice, professional authority, advocacy and professional informant (Hajiesmaello et al, 2020). The scoring of this scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale from the lowest perception of empowerment (1 point) to the highest perception (5 points), and the score of each domain is also based on 5 points. The internal consistency of this scale has been confirmed with Cronbach's alpha above 0.7 (Hajiesmaello et al, 2020). The reliability of the scale was confirmed with Cronbach's alpha of 0.74 in the present study.

To simplify comparison of the scores obtained from the domains of the professional quality of life questionnaire and the perception of empowerment in midwifery scale, the raw scores of each domain were calculated on a scale from 0 to 100 (Skevington et al, 2004). The total score of the questionnaires equaled the sum of the scores of the domains on a scale of 0 to 100, divided by the number of domains. In the professional quality of life questionnaire, all the domains were first converted to 0 to 100, and then the 100-x equation, ie X100= (X-Min)/(Max-Min)x100, was used to align the values of the domains, so that higher scores in all three domains would mean a favorable status. The questionnaires were ranked as follows: 0–33 indicated a low level of the measured quality, eg low professional quality of life, 34–66 was moderate, and 67–100 was high.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences 23 using univariate (t-tests and one-way analysis of variance) and multivariate (Pearson's correlation test and regression analysis) analysis. These were used to evaluate the influence of independent variables as probable predictors of professional quality of life. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Ethical considerations

The participants were provided with explanations about the study objectives and then assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. This study was part of a PhD thesis in reproductive health, with the code of ethics IR.SBMU.PHRMACY.REC.1398.223 from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Results

A total of 411 completed questionnaires (approximately 20% response rate) were received, 31 of which were excluded based on the exclusion criteria; the data from the remaining 380 participants were analysed. The mean age of the participants was 32.7 (8.5) years (ranging from 23–67 years), and their mean work experience was 8.5 (7.9) years (ranging from 1–47 years). The majority had bachelor's degrees (78.4%), were married (63.7%) and worked in hospitals (60%). Under half (45.5%) worked in rotating shifts, and 80% reported moderate or high satisfaction with their profession (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic details of participating midwives

| Variable | Group | Frequency, n=380 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23–30 | 208 (54.7) |

| 31–40 | 97 (25.5) | |

| ≥41 | 75 (19.7) | |

| Marital status | Single | 138 (36.3) |

| Married | 242 (63.7) | |

| Number of children | 0 | 229 (60) |

| 1 | 75 (19.7) | |

| ≥2 | 76 (20) | |

| Education | Associate degree | 10 (2.6) |

| Bachelor's degree | 298 (78.4) | |

| Master's degree or higher | 72 (18.9) | |

| Work experience (years) | 1–2 | 78 (20) |

| 3–10 | 195 (51.3) | |

| 11–20 | 70 (18.4) | |

| ≥21 | 37 (9.7) | |

| Workplace structure | Hospital | 228 (60) |

| Private office | 14 (3.7) | |

| Public health center | 138 (36.3) | |

| Delivering labour and childbirth services | Yes | 186 (48.9) |

| No | 191 (53.3) | |

| Work shift | Day shifts | 197 (51.8) |

| Rotating | 173 (45.5) | |

| Satisfaction with the profession (1–10) | Low (≤4) | 73 (19.2) |

| Moderate (5–7) | 175 (46.1) | |

| High (≥8) | 125 (32.9) |

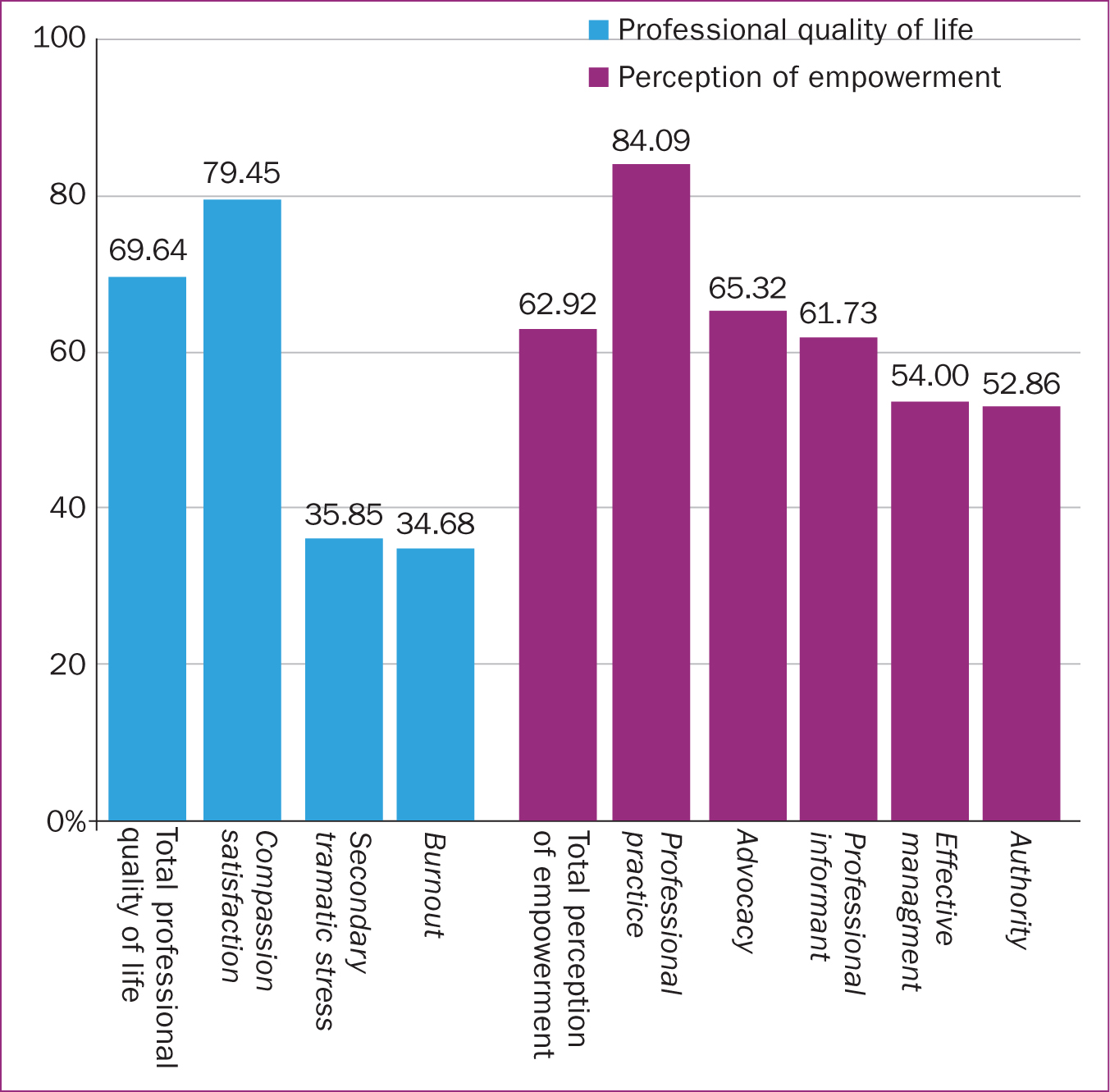

More than half of the participants (59.7%) reported their professional quality of life was high, 81.3% had high compassion satisfaction, 43.2% had moderate burnout and 58.2% had moderate secondary traumatic stress. The mean score of midwives' perception of empowerment based on a scale from 0–100 was 62.92±10.71, and the majority (59.5%) reported their perception of empowerment was moderate. The highest score was observed in the domain of professional practice (84.09±10.93), demonstrating the favorable status of this domain. In addition, the mean scores in effective management, autonomous practice, advocacy and professional informant were 54.00±22.38, 52.85±18.25, 65.31±16.66, and 61.73±17.89 respectively, suggesting moderate levels of perception of empowerment in these domains (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2. Professional quality of life and perception of empowerment scores

| Variable | Crude mean score (standard deviation) | Mean based on 0–100 (standard deviation) | Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | |||

| Overall professional quality of life | N/A* | 69.64 (13.15) | 227 (59.7) | 147 (38.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Compassion satisfaction | 41.78 (5.88) | 61.72 (17.89) | 309 (81.3) | 69 (18.2) | 2 (0.5) |

| Burnout | 11.93 (4.20) | 34.67 (21.02) | 31 (8.2) | 164 (43.2) | 165 (43.4) |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 24.34 (5.09) | 35.85 (12.74) | 6 (1.6) | 221 (58.2) | 153 (40.3) |

| Overall perception of empowerment | 17.71 (2.05) | 62.9 (10.71) | 139 (36.6) | 226 (59.5) | 3 (0.8) |

| Effective management | 3.16 (0.86) | 54.00 (22.38) | 130 (34.2) | 174 (45.8) | 76 (20) |

| Professional practice | 4.36 (0.43) | 84.09 (10.93) | 360 (94.7) | 20 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Autonomous practice | 3.11 (0.73) | 52.85 (18.25) | 68 (17.9) | 240 (63.2) | 72 (18.9) |

| Advocacy | 3.61 (0.66) | 65.31 (16.66) | 166 (43.7) | 192 (50.5) | 22 (5.8) |

| Professional informant | 3.46 (0.71) | 61.73 (17.89) | 115 (30.3) | 238 (62.6) | 27 (7.1) |

The results of the t-test and one-way analysis of variance (univariate analyses) showed a significant relationship between professional quality of life and perception of empowerment (P<0.001), satisfaction with midwifery (P=0.031), and education (P<0.001). There were also significant differences in perception of empowerment scores depending on participants' age (P=0.031), whether or not they provided labour and childbirth services (P=0.01), and their satisfaction with midwifery (P<0.001).

Linear regression showed that midwives' increased perception of empowerment was associated with improvements in overall professional quality of life (P<0.001) as well as with all three domains of professional quality of life: compassion satisfaction (P<0.001), burnout (P<0.001), and secondary traumatic stress (P=0.001). Midwives' perception of empowerment alone predicted 17% of professional quality of life, 17.5% of compassion satisfaction, 13.9% of burnout and 3% of secondary traumatic stress (P<0.001) (Table 3). Univariate linear regression showed that a number of sociodemographic variables were associated with professional quality of life or one of its domains. Age was associated with compassion satisfaction (P=0.01), having an associate degree was associated with overall professional quality of life, compassion satisfaction (P=0.009 for both) and burnout (P=0.02), and satisfaction with the profession was associated with overall professional quality of life (P<0.001) and all three domains (P<0.001 for all three) (Table 4).

Table 3. Univariate linear regression predicting professional quality of life, and its domains, by perception of empowerment

| Outcome variable | R2 | B | Beta | Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall professional quality of life | 0.170 | 0.506 | 0.412 | 0.393–0.619 | <0.001 |

| Compassion satisfaction | 0.175 | 0.577 | 0.420 | 0.450–0.703 | <0.001 |

| Burnout | 0.139 | -0.733 | -0.373 | -0.916–-0.548 | <0.001 |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.031 | -0.210 | -0.179 | -0.328–-0.091 | 0.001 |

Table 4. Univariate linear regression for relationship between demographic characteristics and professional quality of life

| Predictor variable | Overall professional quality of life | Compassion satisfaction | Burnout | Secondary traumatic stress | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Beta | P value | B | Beta | P value | B | Beta | P value | B | Beta | P value | |

| Age | 0.107 | 0.069 | 0.17 | 0.208 | 0.120 | 0.01 | -0.084 | -0.034 | 0.50 | -0.029 | -0.019 | 0.71 |

| Marital status | 0.843 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.107 | 0.069 | 0.17 | -1.445 | -0.033 | 0.52 | -0.194 | -0.007 | 0.88 |

| Work experience | 0.076 | 0.046 | 0.37 | 0.188 | 0.101 | 0.05 | -0.074 | -0.028 | 0.59 | 0.033 | 0.021 | 0.69 |

| Delivering labour and childbirth services | ||||||||||||

| Yes (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No | -0.705 | -0.027 | 0.60 | -0.103 | 0.004 | 0.94 | 2.013 | 0.048 | 0.35 | -0.565 | -0.051 | 0.43 |

| Work shift | ||||||||||||

| Day shifts (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Rotating | -1.724 | -0.065 | 0.21 | -0.562 | -0.019 | 0.71 | 1.658 | 0.063 | 0.22 | -5.931 | -0.075 | 0.14 |

| Qualification | ||||||||||||

| Bachelor's degree (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Associate degree | 11.112 | 0.135 | 0.009 | 12.412 | 0.135 | 0.009 | -14.994 | -0.114 | 0.02 | -5.931 | -0.075 | 0.14 |

| Master's degree or higher | 0.673 | 0.020 | 0.69 | 1.529 | 0.041 | 0.42 | 0.423 | 0.008 | 0.87 | -0.923 | -0.028 | 0.58 |

| Workplace structure | ||||||||||||

| Hospital (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Private office | -1.716 | -0.025 | 0.63 | 2.751 | 0.035 | 0.49 | 4.645 | 0.042 | 0.42 | 3.253 | 0.048 | 0.35 |

| Public health center | 1.451 | 0.053 | 0.30 | 1.475 | 0.048 | 0.35 | -1.222 | 0.028 | 0.59 | -1.656 | -0.063 | 0.22 |

| Satisfaction with profession | 2.967 | 0.534 | <0.001 | 3.192 | 0.512 | <0.001 | -4.345 | -0.490 | <0.001 | -1.363 | -0.252 | <0.001 |

In multivariate analysis, a significant correlation was found between midwives' professional quality of life and their perception of empowerment (P<0.001) (Table 5). This correlation was positive for compassion satisfaction and negative for burnout and secondary traumatic stress, meaning as perception of empowerment increases, compassion satisfaction is also increased while burnout and secondary traumatic stress are decreased.

Table 5. Multivariate regression model for relationship between variables and perception of empowerment with professional quality of life and its domains

| Predictor | Overall professional quality of life Adjusted R2=0.346 | Compassion satisfaction Adjusted R2=0.341 | Burnout Adjusted R2=0.295 | Secondary traumatic stress Adjusted R2=0.072 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Beta | P value | B | Beta | P value | B | Beta | P value | B | Beta | P value | |

| Perception of empowerment | 0.309 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.357 | 0.262 | <0.001 | -0.446 | -0.229 | <0.001 | -0.123 | -0.104 | 0.05 |

| Age | 0.071 | 0.045 | 0.66 | 0.082 | 0.046 | 0.66 | 0.106 | 0.043 | 0.62 | -0.238 | -0.154 | 0.21 |

| Work experience (years) | -0.138 | -0.081 | 0.42 | -0.049 | -0.026 | 0.80 | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.89 | 0.326 | 0.196 | 0.10 |

| Satisfaction with profession (1–10) | 2.478 | 0.443 | <0.001 | 2.591 | 0.414 | <0.001 | -3.663 | -0.410 | <0.001 | -1.180 | -0.217 | <0.001 |

| Qualification | ||||||||||||

| Bachelor's degree (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Associate degree | 10.748 | 0.126 | 0.004 | 11.705 | 0.123 | 0.005 | -15.294 | -0.112 | 0.01 | -5.245 | -0.063 | 0.22 |

| Master's degree or higher | -0.274 | -0.008 | 0.85 | -0.190 | -0.005 | 0.91 | -0.446 | -0.22 | 0.63 | -0.545 | -0.017 | 0.75 |

Assessment of the concurrent effect of the studied variables that had a significant impact on the professional quality of life and its domains showed that, in conjunction with midwives' perception of their empowerment, these variables predicted 34% of the variance in total professional quality of life and compassion satisfaction, 29% of burnout and 7% of secondary stress (Table 5). This prediction was significant for compassion satisfaction, mediated by perception of empowerment, satisfaction with profession and qualification. Each unit increase in perception of empowerment score increased the compassion satisfaction score by 0.3, and each unit increase in satisfaction score (on a scale of 1–10) increased the compassion satisfaction score by 2.5 units (Table 5).

Individuals with associate degrees had 11.7 units higher compassion satisfaction compared to those with bachelor's degrees. In the domain of burnout, each unit increase in the perception of empowerment reduced the burnout score by 0.4 and each unit increase in satisfaction with the profession reduced the burnout score by 3.6. Compared to midwives with bachelor's degrees in midwifery, midwives with associate degrees had 15 units less burnout (Table 5).

Satisfaction with the profession was the only variable that could predict secondary traumatic stress significantly, such that each unit increase in satisfaction with the profession reduced secondary traumatic stress by 1.1 units (Table 5).

Discussion

The results of this study into professional quality of life and perception of empowerment in midwives in Iran found that participants' professional quality of life is affected by their perception of empowerment, not just in terms of skills and practice, but also with regard to management, advocacy and autonomous practice. Factors such as age, education and satisfaction with the profession also had significant effects on professional quality of life.

A higher score in perception of empowerment was linked with increased compassion satisfaction (one unit increase in empowerment resulted in 0.3 unit increase in compassion satisfaction score) and a higher satisfaction score was linked with a higher compassion satisfaction score (one unit increase in satisfaction with the profession resulted in a 2.5 unit increase in compassion satisfaction). The higher positive impact of the satisfaction score on the satisfaction with profession score than the perception of empowerment score on the professional quality of life was attributed by the authors as being the result of the different scales used. Satisfaction with the profession was described on a scale of 10 and perception of empowerment was described on a scale of 100. Therefore, each unit increase in satisfaction with the profession on a scale of 10 is equivalent to 10 units on a scale of 100. If expressed on a scale of 100, a unit increase in satisfaction with the profession can be said to increase professional quality of life by 0.25 units.

Although most midwives reported moderate or in some cases high levels of burnout and secondary traumatic stress, over half of those working in midwifery care reported a high professional quality of life, mostly because of their compassion satisfaction. There were significant levels of burnout and secondary traumatic stress, which could be considered a harmful work environment. However, most midwives enjoyed their work and had moderate to high levels of satisfaction with their profession. One reason for job satisfaction in midwifery may be the diversity of patients (Sullivan et al, 2011). In addition, midwives have reported considering a ‘positive outlook’ and ‘enjoyment’ as the main reasons for their desire to continue working in midwifery (Sullivan et al, 2011), and these factors have also been recognised as reasons for enhanced compassion satisfaction (Radey and Figley, 2007). In a cross-sectional study by Cohen et al (2017), only 1.1% of examined midwives reported low compassion satisfaction, and none reported high levels of burnout and secondary traumatic stress. In contrast, a study conducted in Uganda found that most midwives in rural centers reported moderate compassion satisfaction and only 2.2% had high levels of compassion satisfaction (Muliira and Ssendikadiwa, 2016). Most participants had moderate to high levels of burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Muliira and Ssendikadiwa, 2016). In a cross-sectional study in South Africa, compassion satisfaction was high in healthcare workers providing pregnancy termination services, and burnout and secondary trauma stress were moderate, while compassion satisfaction of the personnel in managerial roles was higher than that of physicians and nurses working in these wards (Teffo et al, 2018). In these studies, the differences in professional quality of life may be the result of factors such as differences in resources, exposure to occupational hazards and stressful situations, as well as the policies adopted by managers in the organisation (Mizuno et al, 2013). A study conducted in Iran on healthcare providers, including midwives, nurses and physicians, found mean scores of compassion satisfaction=38.84 (standard deviation: 6.23), burnout=13.53 (standard deviation: 4.34) and secondary traumatic stress=27.05 (standard deviation: 5.70) in participants (Keshavarz et al, 2019), suggesting unfavorable professional quality of life compared to the present study. The main reasons for the difference between the present study and Keshavarz et al (2019) were differences in study population, different professional conditions, workloads, types of patient care services delivered and severity of illness (Keshavarz et al, 2019).

The majority of participants had a moderate perception of empowerment. The highest scores were in the domain of professional practice, indicating midwives' knowledge and skills. The lowest scores were in the domains of autonomous practice and effective management, which may indicate that the participants felt they had limited decision-making authority and a lack of respect from managers. Studies have shown that organisational differences in advocacy, professional autonomy and occupational control greatly affect midwives' perception of empowerment (Hildingsson et al, 2016; Fenwick et al, 2018; Murat Öztürk et al, 2018). These differences may be the result of the more independent style of midwifery in a health system that is more focused on primary care. In Iran and other countries, such as Cyprus, the midwifery model of natural childbirth is not fully recognised and implemented (Hadjigeorgiou and Coxon, 2014; Sedigh Mobarakabadi et al, 2015; Ardakani et al, 2020), such that even in public hospitals, the role of midwives is not recognised and the continued presence of gynaecologists and obstetricians has reduced midwives' sense of autonomous practice (Pazandeh et al, 2015). The emergence of stressful situations is facilitated following a lack of professional autonomy and limited opportunities to gain experience in midwifery care in high-risk situations (Ahmadi et al, 2018). For midwifery to reach its full potential on a global scale, it is important to foster a developing sense of autonomy in midwives and empower them as a key element in recruiting and retaining midwives (Hildingsson et al, 2016).

Similarly, studies have found that perception of empowerment in different domains, including professional independence and organisational support, can improve professional quality of life. A review study found there were 26 personal and organisational factors that influence burnout (Sidhu et al, 2020). For instance, midwives who worked with the caseload/continuity care model and had more professional independence than midwives working with other care models reported less burnout. Organisational support to balance work and life is another preventive factor for burnout among midwives (Sidhu et al, 2020). A cross-sectional study in the UK reported concerning levels of burnout among midwives, and found that midwives who perceived their emotional health as seriously threatened were more likely to quit (Hunter et al, 2019).

Studies conducted in Iran have reported contradictory results regarding the relationship between occupational burnout and factors such as age, marital status, work experience and work shifts (Esfahani et al, 2012; Behboodi Moghadam et al, 2014; Janighorban et al, 2020). In the present study, midwives with associate degrees had higher compassion satisfaction and lower burnout than those with bachelor's degrees, which could be the result of different career expectations of midwives with higher qualifications working in the same position as those with lower qualifications. This group may feel that, in practice, they have less job control, professional support and autonomous practice than that for which they have been trained and empowered (Demerouti et al, 2001; Müller et al, 2016). A review study by Najjar et al (2009) found that those with higher qualifications and clinical competencies had higher expectations for their job satisfaction. Many of these factors are regarded as empowerment factors; for example, a study in New Zealand found that insufficient resources, lack of advocacy from top managers, lack of recognition of midwives as professionals and lack of promotion opportunities for midwives were associated with occupational burnout (Dixon et al, 2017). Burnout and lack of empowerment in the workplace can lead to reduced self-esteem, disappointment and psycho-emotional crises, which affect professional quality of life (Fenwick et al, 2018).

In the present study, satisfaction with the profession was the only variable that predicted secondary traumatic stress significantly. Two important factors can expose people to secondary traumatic stress: exposure to and frequent awareness of traumatic events (Beck and Gable, 2012). In midwives, this exposure can negatively impact mental health and reduce professional quality of life (Cankaya et al, 2020). Overall, constant exposure to stress and potentially harmful professional experiences contribute to the onset of negative consequences such as reduced job satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress and occupational burnout (Li et al, 2014). Although no significant relationship was observed in the present study between perception of empowerment and secondary traumatic stress, approaches including training, spiritual support and fostering an effective support system in the workplace can reduce the negative impact of secondary traumatic stress and burnout (Tehrani, 2007).

Conclusions

This study examined midwives' perceptions of empowerment and its influence on professional quality of life among midwives from five provinces of Iran. Considering the role of perception of empowerment in the dimensions of effective management, professional practice, autonomous practice, advocacy and professional informant, it seems that strengthening these domains can play an effective role in increasing professional quality of life. However, as a result of the cross-sectional nature of this study, all factors affecting midwives professional quality of life have not been examined in this study.

It is essential to plan and implement strategies to improve empowerment in autonomous practice and management in order to increase the quality of midwives' professional life and their job satisfaction and consequently to promote the quality of maternal care and maternal outcomes. In the present study, the quality of midwives' professional life was only partly explained by their perception of empowerment. It is recommended that further studies investigate other factors responsible for quality of professional life in midwives through other field studies and qualitative research.

Key points

- Having a high professional quality of life is one of the influencing factors on midwives' quality of care and their intention to remain working in midwifery.

- Professional quality of life is influenced by workplace factors and psychosocial distress.

- In this study, the perception of empowerment in midwives was most influenced by professional practice and least influenced by autonomous practice and effective management.

- Midwives' professional quality life is partly affected by their perception of empowerment in workplace.

CPD reflective questions

- How could midwives in your place of work be made to feel empowered and thereby be encouraged to remain in the profession?

- Is there a need for effective strategies to increase midwives' authority in managing low-risk deliveries?

- How can a supportive and compassionate organisational culture be supported and encouraged in midwifery and maternity services?