Mater nal and child health is an important component of reproductive health, which entails the health and wellbeing of both the mother and the child during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. It refers to the accepted means of providing, promoting, preventive, curative and rehabilitative care for the mother and child (Mfuh et al, 2016).

Male partner involvement as a concept was adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994. This concept of male partner involvement was instituted after the remote causes of maternal mortality were traced to cultural factors which were chiefly patriarchy (Okeke et al, 2016). Male partner involvement is seen as the process of changes (social and behavioural) that is needed among men so that they can perform more responsible maternal health roles that will ensure the wellbeing of women and children (Mfuh et al, 2016). In addition, it is an important intervention for promoting maternal health (Yargawa et al, 2015). Active concern and participation in the care of the mother and child through pregnancy and childbirth by the male partner is a simple portrait of the concept of male partner involvement in perinatal care.

Perinatal care encompasses healthcare provided to the mother and child throughout the perinatal period, which, according to the World Health Organization ([WHO], 2018), begins at 154 days of gestation (22 weeks) and ends at seven complete days after birth. The Guidelines for Perinatal Care (2012) given by the American Academy of Paediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, showed that the integrated delivery of care and services during the perinatal period should entail the care rendered to the mother before and during pregnancy, management of labour and childbirth, and also postpartum and neonatal care. The care received by the woman from her male partner during the perinatal period is quite essential to maternal and child health, and contributes significantly to the woman's reproductive life.

Increasing male partner involvement in maternal and child healthcare has been an important strategy to reduce preventable maternal morbidity and mortality (Jennings et al, 2014). The involvement of male partners in maternal and child health is not only important in ensuring the good health of both mother and child but it is also a promising strategy for the promotion of maternal health (Adenike et al, 2013; Dumbaugh et al, 2014). The concept of male partner involvement has been associated with improved maternal and child health outcomes (Yargawa et al, 2015); thus, it has been advocated by the WHO as an essential element for ensuring safer pregnancy (Kululanga et al, 2012). There is a recognition within health promotion that men were an important factor in the health of women and children, as men's actions had direct bearing on the health of their partners and their children (Sternberg et al, 2004). Growing global concern reveals that men play an important role in improving maternal and newborn health, particularly through birth preparedness and complication readiness (Sitefane et al, 2020).

Couples' communication is also identified as a key approach for promoting high-impact health behaviours (Sitefane et al, 2020). Despite the importance of male partner involvement in perinatal care, most African countries have viewed maternal health issues, especially childbirth and family planning, as a woman's affair only (Mfuh et al, 2016; Lowe et al, 2017). Lowe et al (2017) identified sociocultural barriers to male partner involvement in maternal and child health in rural Gambia to include (a) the general perception associated with pregnancy and childbirth as women's domain, (b) husbands' competing job responsibilities, (c) rivalry among co-wives, and (d) fear of mockery. A study by Kiptoo et al (2016) carried out in some sub-county in Kenya further revealed that there were assumptions, and cultural and traditional beliefs, that mostly restricted the active involvement of male partner in perinatal care. Consequently, cultural and traditional beliefs as regard the concept of male involvement can pose as barriers to its effective implementation for the good of mother and child.

In the face of the importance of male involvement in perinatal care in the promotion of positive maternal and child health (as advocated by the WHO), the participation of male partners in Nigeria in providing such care is still poorly demonstrated, as their level of involvement in their wives' healthcare is low (Adenike et al, 2013). This has led to the ongoing development of measures to promote and encourage the involvement of males in perinatal care; and has increased the global recognition of the importance of involving the male partners in reproductive, maternal and child health programmes (Davis et al, 2016).

To achieve the global need of improving maternal and child health, especially in developing countries, there is an imperative need to ensure that male partners are actively involved in every aspect of perinatal care. Male involvement is not only vital but also an important step in the reduction of maternal and newborn deaths (Onchong'a et al, 2016) which can influence the outcomes of pregnancy (Kaye et al, 2014). Besada et al (2016) opined that sensitising men on the importance of participating as a unit in the health of their partners and children is equally vital; formal adoption of a male involvement policy will lend credibility to the importance of the approach in improving patient health outcomes and ensuring systematic implementation of strategies.

There is also a concerted call for the development of national policies which encourages male involvement in every aspect of maternal and child healthcare (Kaye et al, 2014; Amukugo et al, 2016; and Besada et al, 2016). This would be beneficial to streamline approaches across the nation to ensure a wide-scale implementation strategy to promote male involvement. Thus, the aim of this research is to describe the views and perception of the scholastic adult intellectual respondents (postgraduates) about the influence of male involvement in perinatal care on the promotion of maternal and child health, as a means of improving the maternal and child health status in developing countries. This will in turn provide baseline data that will aid in developing measures for improving the poor state of male involvement in Nigeria and Africa at large.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive research design was used in this study

Study setting

The study was carried out in Tafawa Balewa and Abdusalam Abubakar postgraduate Halls of Residence in University of Ibadan. Study population included male and female MSc and PhD students of the University of Ibadan resident in Abdusalam Abubakar and Tafawa Balewa Halls from diverse discipline of study ranging from social sciences, agriculture, arts, humanities, medicine, etc were used in this study

Exclusion criteria:

- MSc and PhD students living in other halls within or outside University of Ibadan campus aside the halls selected for the study

- MSc and PhD students who are unwilling to participate in the study

- MSc and PhD students with any medical/health challenge that can hinder their participation eg students that are sick or visually challenged

Sample size

A sample size of 241 was used in this study from an estimated population of 1 000 students in Tafawa Balewa Hall and Abdusalam Abubakar Hall. Tafawa Balewa Hall has 207 students while Abdusalam Abubakar Hall has 700 students (University of Ibadan, 2018). The sample size was calculated from the formula in equation 1, with assumption of confidence level of 95%, margin of error of 5.5% and estimated population size of 1 000 students.

(1) ( ( z 2 × p ( 1 − p ) ) / e 2 ) / ( 1 + ( z 2 × p ( 1 − p ) ) / ( e 2 N ) )

Where, z = z-score (1.96); e = margin of error (0.055); p = proportion of population (0.5) and N = population size (1 000).

Sampling technique

A cluster sampling technique was used in drawing the sample for the study. The halls of residence for postgraduate students within the university used for this study were Tafawa Balewa Hall and Abdusalam Abubakar Hall. For each of the halls of residence, the blocks within the hall were grouped into male and female blocks.

For Abdusalam Abubakar Hall, there were four blocks (Block A, B, C, D). Block D and A were male blocks. Students living in block A were selected to represent the male populace in Abdusalam Hall. Block C students were used to represent the female populace in Abdusalam Hall for this study. Based on the percentage (about 70%) of students in Abdusalam Abubakar Hall in the total study population (1 000), about 215 students were needed to represent Abdusalam Abubakar Hall in the total sample size. Each block in Abdusalam Abubakar Hall has an average number of 70 rooms, with an average number of two occupants, thus, two blocks were used from Abdusalam Abubakar Hall in this study (Block A and C)

In Tafawa Balewa Hall, there are five blocks (A, B, C, D, E). Block A and E were female blocks and both blocks were used in the study. From the male blocks, only block B and D were used in this study. An average number of 98 respondents (about 30% of sample size) was needed from Tafawa Balewa Hall for this study. With an average number of 36 rooms per block, four blocks were selected from this hall (Block A, B, D, E) for this study to suffice for the number of students needed, in case of unavailability of the students at the point of data collection, due to any personal reason that can be associated to the nature of their course (eg working-schooling, using of the hall as temporal residence, travelling out for project work, etc).

Available occupants in each room in the selected blocks of the halls of residence (Abdusalam Abubakar Hall – Block A and C; Tafawa Balewa Hall – Block A, B, D, E) were used in collecting the data for this study.

Instrument for data collection

A self-structured questionnaire was used in collecting data from the study participants, to assess their perception about improving maternal and child health in developing countries through active male partner involvement in perinatal care.

Reliability of the instrument

A pilot study was carried out to determine the reliability of the instrument. The pretesting of the questionnaire was done among 30 postgraduate students living off-campus and in Obafemi Awolowo Hall, University of Ibadan. These 30 postgraduate students were not included in the study sample. The result from the pilot study was used to revise the instrument for clarity of questions, sequence and order of questions before final administration. The stability of the instrument was measured using Cronbach's alpha (0.648) which made the instrument used reliable.

Validity of the instrument

The instrument was tested for face and content validity. The questionnaire was submitted to the research supervisor for thorough assessment for content and face validity.

Method of data collection

A self-structured questionnaire was used in collecting data. Research assistants were employed to aid in the collection of data having undergone training on how to collect data and maintain research ethical principles during the data collection; thus ensuring their efficiency and maintenance of ethical principle throughout the study.

Data analysis

The questionnaire used to collect information from the participants was sorted out for complete filling and then coded, before being imputed for statistical analysis. A total of 241 questionnaires were fully completed and used in the study with 100% response rate. Responses from the participants were coded to ensure easy analysis of the data. Quantitative data analysis was used in analysing the data collected. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 was used to compute and analyse the data. The statistical tools used were frequency tables and measures of central tendency (mean and mode).

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was received from the Ethical Review Board of University of Ibadan and University College Hospital, with No.: UI/EC/18/0414. Individual informed consent was sought from the respondents for their participation in the study. Explanations as regards the study were given and questions asked were answered before the respondents read and signed the informed consent form. None of the respondents were forced to participate in the study against their will and they were informed of the freedom to withdraw at any time from the study, non-maleficence ethical principle was also ensured.

Anonymity was ensured during data collection, analysis and presentation by only allotting numbers to the form and name of the respondents wasn't required. All information provided by the respondents was kept confidential and only used for academic and research purposes. The completed questionnaires were privately kept in a safe place throughout the period of the study to avoid undue access to respondents' data.

Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of 241 sampled respondents. The mean age of the participant was 27.16±3.48 with an age range of 22–45 years. The distribution of the gender showed that 150 (62.2%) of the respondents are males. The tribal distribution of the respondents indicated that 176 (73.0%) of the respondents were of Yoruba tribe and those belonging to the Igbo and Hausa tribe were 17 (7.1%) and 7 (2.9%) respectively. The academic level of the respondents were either MSc or PhD, of which 215 (89.2%) were MSc. The marital status distribution showed that 212 (88.0%) of the respondents were single and 29 (12.0%) were married.

Table 1. Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents

| Variable | Group | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 91 | 37.8 |

| Male | 150 | 62.2 | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 | |

| Tribe | Igbo | 17 | 7.1 |

| Hausa | 7 | 2.9 | |

| Yoruba | 176 | 73.0 | |

| Others | 41 | 17.0 | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 | |

| Religion | Christianity | 208 | 86.3 |

| Islam | 31 | 12.9 | |

| Others | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 | |

| Academic level | MSc | 215 | 89.2 |

| PhD | 26 | 10.8 | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 | |

| Marital status | Married | 29 | 12.0 |

| Single | 212 | 88.0 | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 20−25 years | 89 | 37.0 |

| 26−31 years | 125 | 51.9 | |

| 32−37 years | 23 | 9.5 | |

| 38−43 years | 3 | 1.2 | |

| 44−49 years | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 241 | 100.0 | |

| Age (mean±standard deviation) 27.16±3.48 | |||

Table 2 shows the influence of active male involvement in perinatal care on maternal and child health. When men get involved in perinatal care, it influences the maternal and child health outcomes as it promotes the safety of the wife's pregnancy and childbirth (90.5%), reduction in maternal and newborn death (50.2%), reduction of any unhealthy behaviour in the wife while promoting positive behaviour (83.8%). It also encourages reduction in maternal stress (83.4%), better health outcomes for the wives and children (69.3%) and reduction of low birth weight, risk of preterm birth, fetal growth restriction and infant mortality (40.0%), although 23.2% of the respondents were undecided about the latter.

Table 2. Influence of active male involvement in perinatal care on maternal and child health of the respondents

| S/N | Content | SA | A | UD | D | SD | Modal response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The safety of their wife's pregnancy and childbirth can be influenced by the role the man plays in their care | 100 (41.5%) | 118 (49.0%) | 13 (5.4%) | 8 (3.3%) | 2 (0.8%) | Agree |

| 2 | Maternal and newborn death cannot be reduced by getting males to be more involved in their care | 24 (10.0%) | 43 (17.8%) | 53 (22.0%) | 92 (38.2%) | 29 (12.0%) | Disagree |

| 3 | When men are involved in perinatal care, they will aid in the reduction of any unhealthy behaviour in the wife and promote positive behaviour | 93 (38.6%) | 109 (45.2%) | 26 (10.8%) | 9 (3.7%) | 4 (1.7%) | Agree |

| 4 | Male involvement has nothing to do with the reduction of low birth weight, risk of preterm birth, fetal growth restriction and infant mortality | 25 (10.4%) | 63 (26.1%) | 56 (23.2%) | 65 (27.0%) | 32 (13.2%) | Disagree |

| 5 | The presence of the man during childbirth will reduce maternal stress and boost her morale | 95 (39.4%) | 106 (44.0%) | 29 (12.0%) | 6 (2.5%) | 5 (2.1%) | Agree |

| 6 | The way at which the man gets involved in perinatal care spells out his sense of commitment to having a healthy mother and baby | 98 (40.7%) | 117 (48.5%) | 18 (7.5%) | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (1.2%) | Agree |

| 7 | Maternal access to care and provision of emotional and financial support is a function of effective male involvement | 96 (39.8%) | 106 (44.0%) | 23 (9.5%) | 11 (4.6%) | 5 (2.1%) | Agree |

| 8 | The involvement of the man in antenatal care does not necessarily cause the wife to visit the antenatal clinic as expected | 14 (5.8%) | 32 (13.3%) | 43 (17.8%) | 111 (46.1%) | 41 (17.0%) | Disagree |

| 9 | The presence and companionship of the man during labour/birth can influence the wife's experience and meaning of the process | 88 (36.5%) | 120 (49.8%) | 27 (11.2%) | 6 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | Agree |

| 10 | When men get involved in their wife's care, their relationship is strengthened | 150 (62.2%) | 73 (30.3%) | 16 (6.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | Strongly agree |

| 11 | Men have social, and tremendous, control over their partners and make vital decisions as regards their wife's health. As such, their involvement is critical in improving maternal health and reducing maternal mortality and morbidity | 90 (37.3%) | 114 (47.3%) | 28 (11.6%) | 9 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | Agree |

| 12 | Women have easier and quicker access to healthcare when their husband is fully involved in their health needs | 79 (32.8%) | 94 (39.0%) | 50 (20.7%) | 13 (5.4%) | 5 (2.1%) | Agree |

| 13 | Male involvement is an important avenue for giving men information so they can support healthy behaviours and healthcare seeking for children, such as exclusive breastfeeding and childhood immunisation | 115 (47.7%) | 96 (39.8%) | 25 (10.4%) | 5 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | Strongly agree |

| 14 | Wives and children of actively involved males have better health outcomes than those whose husbands don't get involved in their care | 81 (33.6%) | 86 (35.7%) | 52 (21.6%) | 17 (7.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | Agree |

Additionally, 83.8% of the respondents also agreed that maternal access to care and provision of emotional and financial support is a function of effective male involvement, as women have easier and quicker access to healthcare when their husband is fully involved in their health needs (71.8%). Consequently, when males get involved in perinatal care, it spells out their sense of commitment to having healthy mother and baby (89.2%), influences the wife's experience and meaning of the labour/birth process (86.3%) and strengthens their relationship with their wife (92.5%).

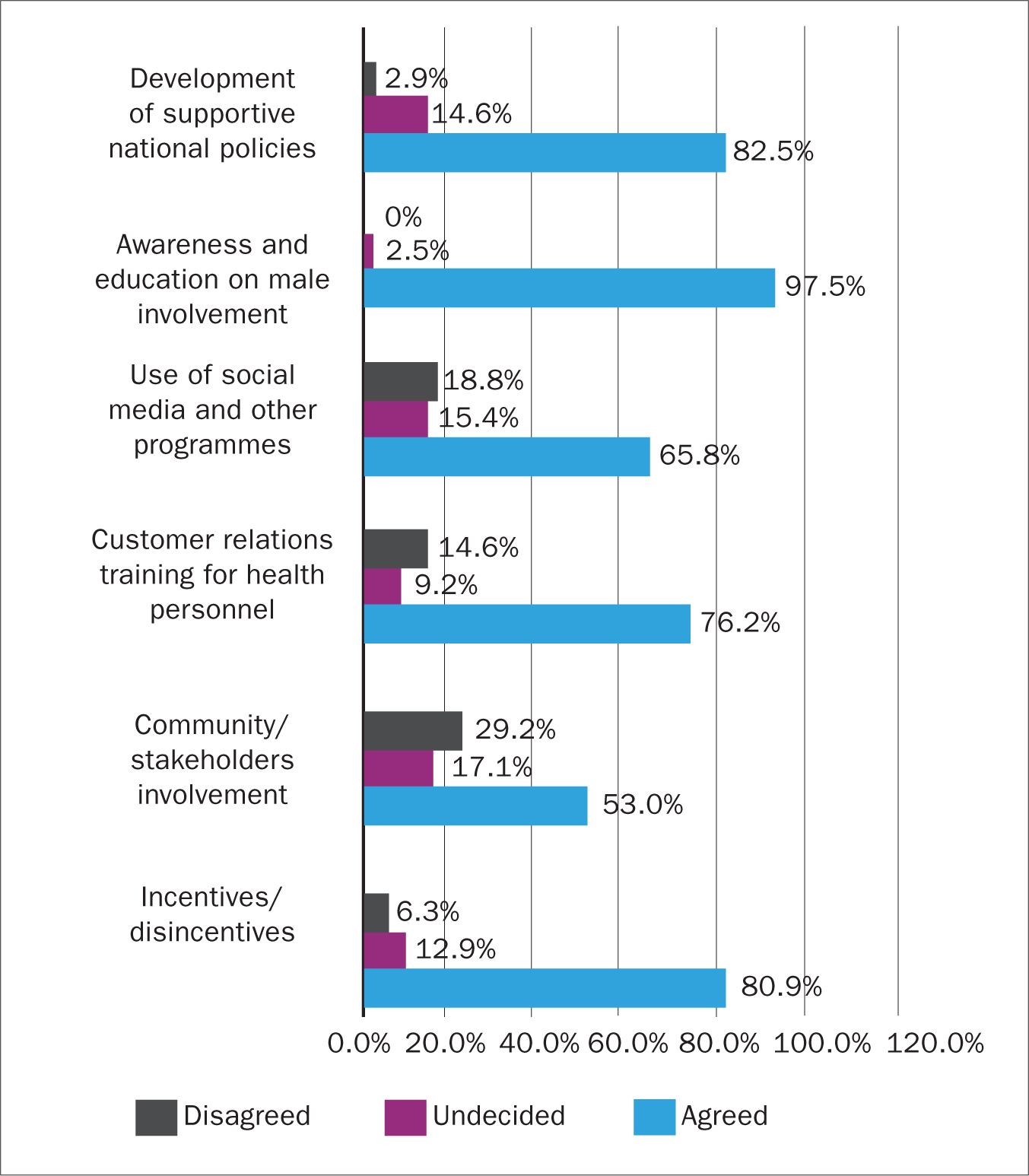

Figure 1 shows the perceived suggestions by the respondents for improving active male involvement in perinatal care services. Most of the respondents suggested an increase level of awareness and education of what male involvement entails (97.5%), development of national policies to ensure the participation of males in every aspect of maternal and child healthcare (82.5%), integration of other programmes outside the health sector like social media (65.8%), training of healthcare providers on customer care, communication skills and relations (70.2%), active involvement of the community members and stakeholders (53.0%), and the active use of incentives/disincentives (eg free male health check-up, free antenatal care for women accompanied by partners, certificates for couple testing, prioritisation for women accompanied by a male partner, partner invitation letters and fines for partners) by hospital facilities (80.9%). Also, majority of the respondents agreed that to promote male involvement in perinatal care, women also should have adequate and accurate knowledge on male partner involvement and its benefits; not just the males (94.1%).

Figure 1. Perceived suggestions for improving active male involvement in perinatal care

Figure 1. Perceived suggestions for improving active male involvement in perinatal care

Discussions

In this study, both male and female respondents were involved so as to ensure presentation of the perception of both gender, although, majority of the respondents were males (62.2%). This is different from the approach used by Okeke et al (2016) in the study they conducted in one of the Southern states in Nigeria, where only the perception of the female gender was used in the study.

Influence of active male involvement in perinatal care on maternal and child health

Active male partners' involvement at every level of perinatal care can influence maternal and child health at varying points. These cumulative influences of male involvement can go a long way to improving the general maternal and child health status.

In this study, more than half of the respondents were of a strong opinion that the involvement of male partners during the perinatal period can result in reduction of maternal and newborn death. This finding was similarly reported in the study by Adenike et al (2013) and Onchong'a et al (2016) where males are seen as critical partners in the reduction of maternal and newborn mortality.

Promotion of the safety of the mother and child during pregnancy was also perceived by the respondents in this study to be a product of active male partner involvement. Majority of the respondents stated that there will be a reduction in any unhealthy behaviour in the wife like intimate partner violence during pregnancy and promotion of positive behaviour when the male partner is involved in her care such as care for the family, adequate nutrition for the wife and family, etc. This is related to the findings in several studies by Alio et al (2013); Kaye et al (2014) and Onchong'a et al (2016); where it was reported that the involvement of male partners during the perinatal period plays a vital role in the safety of their female partners' pregnancy and childbirth, as well as reduces negative maternal behaviours.

Preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction and infant mortality are detrimental factors to the improvement of maternal and child health in any country. In this study, these factors were perceived by most of the respondents to be linked to male partner involvement, and just like it was reported in the study by Kaye et al (2014), the involvement of males can reduce the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction and infant mortality by providing spousal support in terms of adequate nutrition, rest, safety and encouraging regular attendance at antenatal clinics where these deviations in normal pregnancy can be identified early and managed promptly thus improving child health.

Regular attendance of pregnant women to antenatal clinics has been one of the solicited measures for improving maternal and child health. With the majority of the respondents in this study being of a strong opinion that if male partners are involved in the perinatal care, it will positively influence how their wife attends the antenatal clinic, it shows how the involvement of male partner can be influential in the promotion of maternal and child health. Mkandawire et al (2018) and August et al (2016) similarly reported male involvement to have a positive influence on the attendance of women to antenatal clinics including their compliance with breastfeeding and family planning. A spouse who accompanies their wife to the antenatal clinic or provides a strong support for these visits will ensure compliance to the antenatal routine. Also, teachings or educative instructions given during such visits will be enforced and integrated into the care of the baby, especially exclusive breastfeeding.

Apart from improving the physiological health of both the mother and child through active male involvement, the respondents in this study also reported that male involvement could promote emotional maternal health through the reduction of maternal stress by being physically available to take care of the family and providing financial support which, on the other hand, also boosts the morale of the wife throughout the pregnancy. Most of the respondents were also of the opinion that the involvement of the male partner in the perinatal care gives a strong proof of the spouse commitment to the wellbeing of the expectant mother and baby, though the male physical presence in some families might increase the risk of intimate partner violence which had been discovered to be on the rise during pregnancy. Similar results were reported in the studies by Alio et al (2013) and Adenike et al (2013), where it was strongly opined that the involvement of male partners during pregnancy, including their physical presence in the health facility, will reduce maternal stress levels, boost their morale and also bring about a greater sense of commitment of both parents to having healthy mothers and babies.

The majority of the respondents in this study viewed male partner involvement in perinatal care as a necessity for improving maternal and child health outcomes. They strongly agreed that wives and children of actively involved male partners have better health outcomes than those whose husbands don't get involved in their care. This is because these male partners will be able to make rational decisions as regards the health of the family by taking prompt steps to seek for care, thereby reducing complications setting in, though some husbands might act indifferent to health issues of the family. This opinion was supported by the findings of Alio et al (2013) and Kaye et al (2014) where positive male involvement was said to improve the health outcome of both the mother and child, and even influence pregnancy outcomes.

Perceived suggestions for improving active male involvement in perinatal care

The findings of this study have shown that active involvement of male partners in perinatal care is key to ensuring the improvement of the maternal and child health, especially in developing countries. Despite the obvious importance of male involvement in perinatal care on maternal and child health, several studies have shown that its implementation is poor, especially in developing countries. Therefore, some suggested measures for improving male partner involvement was obtained from the respondents in this study.

An increased level of awareness and education on what male involvement entails, with its attributed benefit, was suggested by the majority of respondents. Additionally, most of the respondents were of the opinion that social media and other non-health platforms should be integrated in the promotion of male partner involvement. These suggestions were similarly seen in the study by Kaye et al (2014), and was emphasised in the WHO Geneva meeting in 2002, where the need to create awareness, ensure adequate dissemination of information and enlist the support of programmes outside the health sector was recognised.

Development of national policies to support and back up active male involvement was also suggested by a very large percentage of the respondents. The findings in the study by Kaye et al (2014), Amukugo et al (2016) and Besada et al (2016) stated similar suggestion, as government officials were encouraged in these studies, to set up male involvement supportive national policies.

The need to empower the women with adequate and accurate knowledge about active male partner involvement was also suggested by the majority of respondents in this study. Similar suggestions were seen in the study by August et al (2016), Davis et al (2016), Okeke et al (2016) and Onchong'a et al (2016), where an increase of the knowledge of not just men but women also is vital in ensuring male partner involvement.

The majority of the respondents also added that for males to be actively involved in perinatal care services, healthcare professionals need to be trained on customer care, communication skills and relations; incentives and disincentives should be used by hospital facilities to foster male partner involvement; and community members and stakeholders should be actively involved. Similar suggestions were seen in several studies by Kululanga et al (2012), Kaye et al (2014), August et al (2016), Besada et al (2016), Okeke et al (2016) and Mkandawire et al (2018).

To effectively implement active male partner involvement in perinatal care services, necessary changes and collaborations need to be made by the individuals, families, health workers, health facilities, community members, stakeholders, policymakers and the government.

Conclusion

Maternal and child health is one of the major health priorities of every nation. Due to the poor maternal and child health in developing countries, the need for active male partner involvement has been solicited over the years. The influence of active male involvement in perinatal care, in improving the maternal and child health outcomes, has been shown in this study. Evidently, male partner involvement in perinatal care services will largely foster positive maternal and child health through its positive effect on the mother and child during the antenatal, intranatal and postnatal period. Suggestions as perceived by the respondents, on how to improve the implementation of male involvement in perinatal care, has shown the need for joint effort in order to promote active male partner involvement in perinatal care, which will in turn improve maternal and child health outcomes. These suggestions can be proffer baseline data for implementation studies to determine the effectiveness of each suggestion in improving active male involvement.

Key points

- Male partner involvement in perinatal care reduces maternal and newborn death

- Male partner involvement increases attendance and compliance to antenatal clinics, breastfeeding and family planning

- Emotional and behavioural health of the mother is fostered by active male partner involvement in perinatal care

- Wives and children of actively involved male partners have better health outcomes

- For effective male partner involvement, collaborations between individuals, families, health workers, health facilities, community members, stakeholders, policymakers and the government are needed

CPD reflective questions

- Studies have shown that one of the major challenges in improving maternal health is the perception of perinatal care services as a ‘woman only’ affair. Is this perception common in your locality? And if yes, what can be done to change such perception?

- Reduction in stress, behavioural change and increased antenatal clinic attendance, are some of the identified influences of male partner involvement in perinatal care on maternal and child health. What other positive influence of male partner involvement have you noticed among mothers and children of actively involved males?

- Use of incentives/disincentives by the hospital facility has been suggested as a measure to improve male partner involvement in perinatal care. Can you suggest ways hospital facilities can apply this method in fostering male partner involvement in their institution?