There is common agreement that the three key elements of informed consent, voluntarism, information disclosure (Office for Human Research Protections, 1979) and the decision-making capacity of an individual should underpin the ethical basis to a study's recruitment strategy (World Medical Association, 1964). However, it can be challenging to ensure that these elements apply when seeking informed consent from women who choose to participate in research studies where interventions are initiated during the intrapartum period (Dhumale and Gouder, 2017). Decision-making capacity can be hindered by a number of factors which interfere with truly informed consent: lack of sleep, opiate analgesia and pain (Vernon et al, 2006).

The process of deciding whether to take part in such studies is also influenced by contextual factors such as the environment, timing of consent in relation to birth, birthing support, the participant's physical and/or mental state and the user-friendliness of the study information given to women (Tooher et al, 2008). Maternity research interventions can be particularly complex. Women are required to understand the purpose of the study, the study interventions, as well as their right to withdraw, risks and benefits of participation for both themselves and their baby, how results will be shared, and how confidentiality will be maintained. It could be argued that the recruitment consultation, the sharing of study information and the researcher's assessment of the woman's capacity to have a full understanding of all aspects of the study, are fundamental to the validity of the consent process (Flory and Emanuel, 2004; Nishimura et al, 2013).

About 21 years ago, ‘A Charter for Ethical Research in Maternity Care’ was published by the association for improvements in the maternity services ([AIMS], 1997) affirming that ‘research should be undertaken with women, not on women’ and ethical concerns regarding the failure of researchers to involve women in the research process were raised. The authors concluded that information should be provided well in advance of the recruitment consultation and that consent should be given as close to treatment as possible (Adnan et al, 2018). However, despite the publication of this charter, there is still evidence that current practice for providing information varies considerably (Dhumale and Goudar, 2017).

AIMS (1997) concerns stemmed from their discussions with national maternity organisations, which argued that women felt vulnerable in labour or powerless to decline participation in a hospital setting if they were not equipped with prior study information. There was a feeling that pregnant women were conforming and giving their consent to participate in research in a state of vulnerability (Frunza and Sandu, 2017) brought about by an altered capacity and autonomy, and where the same decision may not have been made if they were physically comfortable and emotionally secure (Sheppard, 2016). There may also be a perception of an unfair balance of power in favour of the researcher; not because the woman has lost her autonomy entirely but because of the very subtle dependant nature of the midwife/doctor/woman relationship (Patel et al, 2011). Women are dependent on their caregivers and want to appease to prevent alienation from them (Phipps et al, 2013), especially while in labour (Patel et al, 2011).

In 2016, the global forum on bioethics in research (Hunt, 2016) described this as a ‘deferential’ vulnerability. The forum felt that there should be a move away from the general categorisation of women being vulnerable per se to how we can better protect pregnant women with more targeted approaches to informed consent. Some agree with the forum's notion (Hunt, 2016) yet fail to define what makes women particularly vulnerable (Vernon et al, 2006); others such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists ([RCOG], 2016) still recognise the physical and psychological vulnerability of women, whereas the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2015) believe that pregnant women who participate in research studies should be classed as ‘scientifically complex’ rather than a vulnerable population.

The application of this concept, despite its intended protective purpose and widespread use within research, has caused significant disagreements within the research ethics standards as to its use (Bracken-Roche et al, 2017). While it is understandable that the tragedies of Thalidomide and Diethylstilbestrol have resulted in perhaps an overprotection of pregnant women (van der Graaf et al, 2018), this has led to a dearth of studies, particularly medication studies, and it could be argued that this lack of research has made pregnant women more vulnerable because of the absence of scientific knowledge (Hunt, 2016). It is essential that the discussion between the researcher and the woman should create a space in which women feel at liberty to either accept or refuse participation. The processes that study teams use to engage with women, and by which recruitment is achieved, can influence a woman's decision to take part in research (Baker et al, 2005). The RCOG's (2016) proportionate stance on obtaining consent to participate in maternity research places women in the development, delivery and publication of the study, including reviewing the information provision and the consent process. However, despite the RCOG's position, little is known about how potential participation in intrapartum studies is discussed and this formed the rationale for this feasibility study

Aim

To investigate how information about a research study with an intrapartum intervention – ASSIST – was presented to potential participants and to report on the acceptability of the information provision given to women by midwives.

Methods

The ASSIST study investigated the clinical impact, safety and acceptability of the BD Odon Device, a novel device for assisted vaginal birth and is reported in detail elsewhere (O'Brien et al, 2019; Hotton et al, 2020 still in press). The study was conducted at Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust between October 2018 and April 2019. A total of 40 women who required an assisted vaginal birth for a clinical indication had their birth assisted with the BD Odon Device.

Due to the interventional nature of the study, it was not known how many women would consent to participate. Therefore, a sub-study was embedded within ASSIST, using audio-recorded consultations and interviews to investigate how study information was presented to potential participants and how they responded using a methodology developed to investigate recruitment consultations for randomised controlled trials (Wade et al, 2009; Donovan et al, 2016). The feasibility and acceptability of the methodology to both women and midwives involved in consent processes for interventions initiated up to, and including, the intrapartum period was studied.

The procedure for recruitment into ASSIST involved research midwives approaching women to offer written information, the opportunity to view a seven-minute information video and a face-to-face discussion about the study with a member of the research team (O'Brien et al, 2019). The full eligibility and exclusion criteria to participate in the study are detailed in the study protocol (O'Brien et al, 2019). To be a participant in the study, women had to require an assisted vaginal birth of a singleton pregnancy at term. The assisted vaginal birth rate at the Trust was 12% it was known at the outset that most women approached and recruited would not require the intervention. As many eligible women as possible were approached and given study information, from admission into the maternity unit up until the start of the second stage of labour, as long as they were pain-free with effective regional analgesia. All women who had given written consent had their consent re-confirmed at the point when any decision was made to attempt an assisted vaginal birth. Most women who were approached were nulliparous and were given information about the study, either when they attended the antenatal ward for a planned induction of labour or if they attended the antenatal admissions unit for a review.

Three research midwives with prior experience of recruiting to an interventional intrapartum study (van der Nelson, 2019) and two research midwives with no previous experience were responsible for recruitment to ASSIST. The novice midwives were given guidance on how to present the information before they approached women. All research midwives were invited to participate in this feasibility study, with three of the five (60%) consenting to audio record their recruitment consultations; two (midwives B and C) were experienced and one (midwife A) was new to research. The two midwives who chose not to participate in the audio recordings had 15 years' clinical and three years' research experience, and 10 years' clinical and no previous research experience, respectively.

Overall, the five research midwives screened pregnancy notes of 545 women. Of these, 441 (81%) women were initially deemed eligible and approached. A total of 57 of those approached were subsequently found to be ineligible and therefore not recruited. Of the 384 women who were approached and eligible, 298 (77.6%) consented to participate should they require an assisted vaginal birth. A total of 86 women (22.4%) declined to participate in the study; the majority provided no reason (n=29; 7.6%). The four most common reasons women gave for declining to participate were: the device is too new (n=13; 3.4%); taking part in research will be too stressful (n=9; 2.3%); do not like the idea of the device (n=8; 2.1%) and do not want to take part in research (n=8; 2.1%). Two women (0.7%) withdrew from the study following their initial consent, both in the antenatal period. No women withdrew consent at the time a decision to perform an assisted vaginal birth was made (Hotton et al, 2020 still in press).

Participants

A convenience sample of eight consecutively ‘eligible to participate’ antenatal women were invited to consent to an audio recording of the conversation during which trial participation was discussed (the ‘recruitment consultation’). Seven (88%) agreed. None of the women had prior study information or were in pain. The woman who declined to be audio recorded also went on to decline participation in ASSIST (Table 1). A further six women who had previously consented to participate in ASSIST but were unable to do so due to study completion were invited to take part in a structured interview about their experiences of the recruitment consultation; all six agreed (Table 2).

| Inter-viewed by midwife | Declined or accepted audio recording | Declined or accepted invitation to participate in the ASSIST study | Reason for admission to maternity unit | Age | Parity | Where was the audio recording conducted? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Accepted | Accepted | Induction | 29 | 1 | Antenatal ward |

| A | Accepted | Accepted | Induction | 24 | 0 | Antenatal ward |

| A | Declined | Declined | Induction | 30 | 2 | N/A |

| B | Accepted | Accepted | Induction | 36 | 1 | Antenatal ward |

| B | Accepted | Accepted | In labour | 33 | 0 | Delivery suite |

| B | Accepted | Accepted | Induction | 28 | 0 | Antenatal ward |

| C | Accepted | Accepted | Induction | 37 | 0 | Delivery suite |

| C | Accepted | Accepted | Induction | 37 | 1 | Antenatal ward |

| Location of interview with Mary Alvarez – senior research midwife | Parity | Was the video helpful? | Was the leaflet helpful? | Was the conduct of midwife positive? | Did you have enough time to consider participation? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal ward | Multiparous | Yes | No | ‘Midwife clear’ | Yes, 30 minutes |

| Delivery suite | Nulliparous | Yes | No | ‘Not pressured’ | Yes, 10 minutes |

| Via telephone | Multiparous | Yes | No | ‘Nice lady’ | No, felt ill |

| Antenatal ward | Nulliparous | Yes | Unsure | ‘Brilliant positive’ | Yes, 10 minutes |

| Via telephone | Nulliparous | Yes | No | ‘Lovely’ | Yes, 10 minutes |

| Via telephone | Nulliparous | Yes | Yes | ‘Informative’ | Yes, immediate |

Data collection

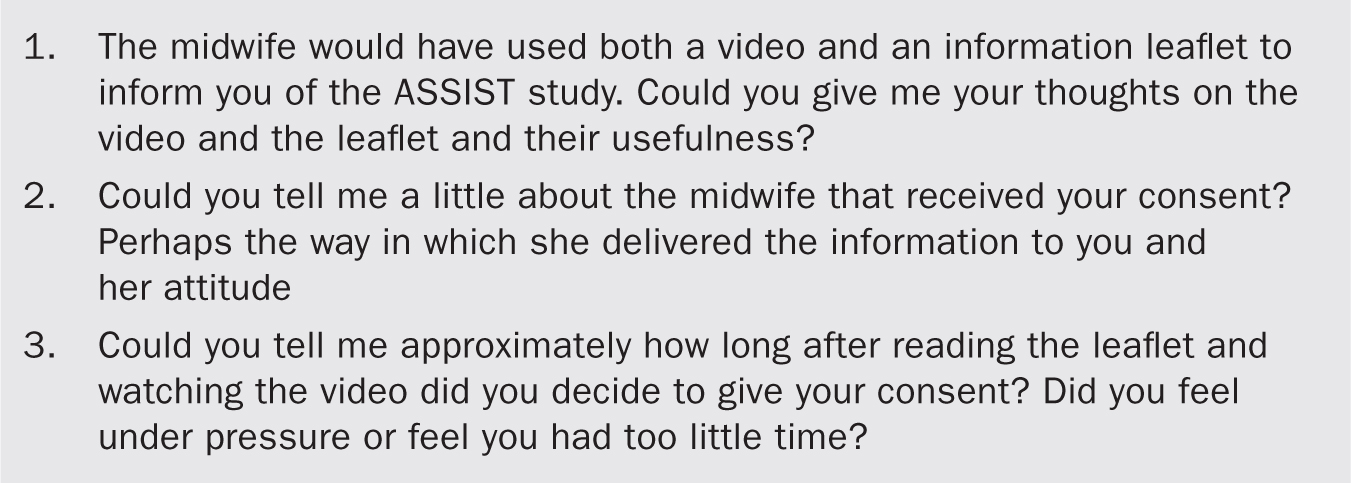

Audio recording of the seven recruitment consultations took place on the antenatal ward or on the delivery suite using the Olympus DS-3500 digital voice recorder. The six follow-up, structured interviews were conducted by telephone (n=3) or in person on the antenatal ward or delivery suite. Interviews were structured following the format outlined in Figure 1. Field notes were taken of any comments that midwives made on carrying out the audio recordings of the recruitment consultations, as well as their responses to feedback on elements of good practice. The structured interviews were not audio recorded but field notes were collected at the time of the interviews.

Data analysis

Audio recordings of recruitment discussions were transcribed verbatim. Data analysis combined simple descriptive quantitative data and content analysis. Transcriptions were reviewed independently by the authors with the aim of identifying content that appeared to facilitate or hinder understanding. Analysis used techniques of content analysis but also looked for evidence of understanding or misunderstanding in the responses of women.

Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by discussion to reach a consensus on what content was helpful and what content was less helpful to women. These data were summarised for use in tailored feedback to midwives and for comparison with reflections from women and midwives obtained during the structured interviews. A simple ‘hints and tips’ document was compiled in order to provide feedback to midwives who had taken part in the audio recordings to highlight both good practice and areas that could be improved.

Findings

These findings are from audio recordings and ‘hints and tips’ guidance feedback.

Findings from content analysis

The three midwives introduced themselves and gave accurate study-specific information.

‘My name is Midwife C and I work as part of the research team. I also work on delivery suite as well, so sometimes you might see me wearing blue scrubs as well. I am going to talk to you about a piece of research we are doing called the ASSIST study. Now, me coming to talk to you doesn't mean that I think you are going to have an assisted vaginal birth … do you know what I mean by assistance?’

However, the midwives did not always mention the study by name.

‘Hello, I have come to see you about the study. Have you had any information about the study?’

The two more experienced midwives, B and C, explained ASSIST in detail before showing the video. In comparison, the less experienced research midwife (A) introduced the video early in the exchange.

‘It is called the BD Odon Device and it's been developed in conjunction with the World Health Organization and BD the medical manufacturer, and it's an air cuff which sits over the baby's head with a plastic sleeve and I am going to show you a video which talks to you and actually shows you how it works.’

This pre-empted many of the questions posed to midwives B and C. For example, many women were concerned about how their baby would breathe with the device over the baby's head and this had been explained in the video.

‘No, because the cuff is only on the baby's head when baby is inside and, at that point, it receives oxygen through its cord. It's not actually breathing and the cuff comes off before the baby is delivered.’

Optimism bias was evident in information given by all midwives: the suggestion there would be less trauma to the mother and baby using the BD Odon Device compared to the conventional instruments used to assist birth (ventouse and forceps).

‘So there is hope then it will be less dramatic for the baby and also less traumatic for you, as forceps are so hard and wider, and the ventouse has got a hard bit too.’

In other consultations, there was more evidence of equipoise.

‘And you said there would be less trauma to the mother?’

‘That's what we are looking at. Obviously, it's a study that's one of the outcomes we are looking at. In theory, it would be as its inflatable and there is nothing hard inside.’

The consultations were also used to explain complex medical terminology and to explain procedures such as an episiotomy.

‘Oh, an episiotomy. Yes, so an episiotomy, that is a cut to widen the vagina, they would always do it with a forceps … they don't always do one with a ventouse. The doctors take lots of things into consideration, like how well the perineum is stretching and the baby's heart rate, and this will be the same as the [BD] Odon Device. The doctor at the time will make that decision.’

Feedback to midwives

Individual feedback was given to the midwives by author Alvarez. Personalised ‘what you did well’ and ‘even better if…’ comments were initially conveyed to each midwife. Before each was given the ‘hints and tips’ document, a compilation of comments designed to be used as a guide to inform and optimise future practice. All three midwives immediately recognised the phrases, sentences, terminology and explanations they had used with the women. Feedback focussed on structure of discussion, use of language and raised awareness of optimism bias. Every attempt was made to keep feedback positive. The Hawthorne effect (McCambridge et al, 2014) on the recruitment consultation could not be discounted as the midwives were aware that the recordings would be subject to content analysis. Alvarez tried to minimise the effect by not attending the recruitment consultations. Even so, the midwives did not enjoy the process, reporting feeling under pressure to perform well.

At the time of the feedback, all expressed gratitude for the feedback and how it would inform their practice. Within three weeks, all three midwives approached author Alvarez to report that, although the feedback had been challenging to listen to and they felt a little ‘bruised’ at the time of feedback, with hindsight, they felt the feedback had been instructive and had enhanced their practice. The delivery of the feedback was challenging for Alvarez but was overcome with the collective professional objective of optimising recruitment to ASSIST.

Study video and patient information leaflet

All six women felt that the video was useful and used words such as ‘engaging’, ‘informative’, ‘simplified the BD Odon birth’. One woman also felt reassured that the midwife discussing the study with her was also on the study video. In contrast, the patient information leaflet was not felt to be useful by most of the women. The woman who found the patient information leaflet helpful was a midwife who worked in the unit where the study was taking place; she valued being able to take the information home with her.

Another women described the patient information leaflet as ‘off putting’ and ‘wordy’. One of the women couldn't remember having been given a patient information leaflet and another woman only read the patient information leaflet after consenting to ASSIST.

Delivery of study information

All the women described the midwives positively. Words such as ‘nice’, ‘lovely’, ‘informative’ and ‘mellowed me’ were used. Five of the six women felt the research midwives were informative and appreciated their approach: conversations were clear and the midwives took the time to make sure that they had gained an understanding of the study before they received consent. It was surprising to find that the sixth woman only agreed to participate in the study in order to be left alone, as she was not feeling well. This information was fed back to the recruiting midwife who confirmed that she had not been aware of this at the time of consent.

Time to consider participation

Five of the six women had no prior knowledge of the study at the time of the consultation but all felt they had enough time to consider the study. Only one of the women read the patient information leaflet prior to consenting. None of the six women were in pain but one reported feeling that being approached in labour for the first time was too late. Another woman felt under pressure to consent, and three of the women commented that information provision should have been given in the third trimester and prior to being approached in the hospital setting. The views of the women interviewed are summarised in Table 2.

Discussion

The audio recording of recruitment consultations was acceptable to participants and offered new insights into the optimal timing for receiving study information and how women valued the video as a format for providing this information. Audio recordings have previously been used to explore the views and experiences of women and researchers who participated and received consent in peripartum trials in order to optimise research and participant satisfaction (Smyth et al, 2012; Lawton et al, 2016) and also to explore how health professionals present study data to potential participants (Rooshenas et al, 2016). These papers highlight how difficult it can be to present interventions in a neutral way.

We noted similar patterns in our data where midwives were unwittingly presenting the BD Odon Device as a potentially a ‘better’ option than current practice. Consultations gave insight into the value of the study information video for potential participants as it simplified the technical manoeuvres of the BD Odon Device. This contrasted with the patient information leaflet which was regarded generally as less helpful, with one woman not recalling having been given a leaflet at all. These negative findings of the patient information leaflet agree with the views of women who consented to the qualitative understanding of trial experience (QUOTE) study (Smyth et al, 2012) investigating the use of prophylactic anticonvulsants for women with severe pre-eclampsia. Women were first given information about the study at the time the intervention was required. Of the 40 women interviewed, 28 remembered being given a patient information leaflet, eight could not recall being given the patient information leaflet and four women were unsure.

Weston et al (1996) observed that video use, coupled with a patient information leaflet, resulted in increased participation and a greater amount of study information being retained 2–4 weeks later. However, Flory and Emanuel's (2004) systematic review of interventions to improve understanding by research participants found that although the use of multimedia is useful in standardising disclosure, it is the engagement with the study team that is more likely to improve understanding. The audio recording of consultations highlighted some excellent practice. Indeed, midwife A's approach of playing the video before engaging in a study discussion was subsequently adopted by the whole study team and will be used as standard practice in the ASSIST II study.

The time given to consider participation was deemed acceptable by all the women who consented to ASSIST. The Health Research Authority (2017) provides no definitive guidelines on the amount of time needed to consider participation; participants can take as long as required without feeling under pressure to participate. However, the time taken to decide on participation has been found to correlate with the perceived risks to the baby (Tooher et al, 2008). The time taken to consider participation in this sample ranged from 10–30 minutes after being given the patient information leaflet, study video and an initial conversation with the midwife. ASSIST was a complex interventional study and despite the potential use of a novel device, five out of six women felt they had enough time to make an informed decision relating to consent.

The majority of women (88%) and 60% midwives found the audio recording of the recruitment discussion acceptable. The audio recording of the recruitment discussion enabled feedback to be given to the research midwives and this facilitated an opportunity for them to reflect on their consenting practice. Although initially often perceived as criticism, feedback was ultimately experienced as a positive and the authors believe is worth repeating in future studies. One limitation of the study is the transferability of the data, due to the small numbers of recruitment consultations and structured interviews analysed. Furthermore, only three of the five midwife researchers opted to audio record their recruitment consultations.

As a senior research midwife, Alvarez was aware of her influence on the research. She acknowledged her reflexivity and critically considered her impact (Braun and Clarke, 2013) as well as her insider status (Gallais, 2008) as a mother and experienced midwife during the structured interviews. The influence she had on the midwives as their manager during the data collection and dissemination of the findings was also considered. The two midwives who did not audio record were never asked their reasons for choosing not to. The midwives who agreed to audio record the recruitment process felt it enhanced their future consultations and enabled sharing of good practice.

The embedding of the audio recordings within the main ASSIST study allowed insight into the consenting process. This process will continue as the model of assessment of information provision and receiving of informed consent for the ASSIST II study is evaluated. The aim of this follow-on, integrated study is to gain further information on women's views on the optimum process of obtaining informed consent for research that involves procedures initiated during the intrapartum period. This qualitative study will explore in greater depth women's and midwives' experiences of information provision and informed consent to identify what was helpful and what could be improved. The study will consider how women's views and ideas on pragmatic information dissemination can inform good practice for receiving consent for research involving an intervention initiated during the intrapartum period, with reference to the ethics literature on best practice for consent in this context.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using audio recorded data and interviews to gain insight into midwives' practice in providing information about research studies and women's experiences of being invited to take part. These methods can be used to investigate the quality of information provision provided by researchers and women's experiences of being given this information, with a view to identifying optimum practices for information provision and participant understanding in the intrapartum period. The goal in the longer term will be to ensure the most effective method of information transfer for participant understanding.