Teenage mothers are a vulnerable group in maternity services, owing to factors including poor health and social exclusion (Department for Education and Skills, 2006). They often have poorer obstetric outcomes than older women, and are more likely to give birth prematurely or have low birth-weight babies (Gupta et al, 2008). Teenage mothers are known to be more likely to smoke, may have a poor diet, develop postnatal depression and have repeated unplanned pregnancies (Public Health England (PHE) et al, 2015). Their access to maternity services is often poorer than older women's, their pregnancies are associated with increased adverse outcomes and poorer long-term health, and they are more likely to be socially excluded (Whitworth and Cockerill, 2014). In addition, many teenage mothers tend to have low prior educational attainment (Crawford et al, 2013).

There has been a downward trend in the rates of ≤ 18-year-old conception rates since 2007; rates are now at their lowest since 1969 (Office for National Statistics, 2015). According to the Teenage Pregnancy Independent Advisory Committee (Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) and Department of Health (DH), 2010), the reduction in teen pregnancy rates can be partly attributed to the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (Social Exclusion Unit, 1999). However, teenage pregnancy remains a major public health concern (DH, 2013). Inadequate antenatal care may place teenagers at markedly elevated risks of eclampsia, urinary tract infections and adverse neonatal outcomes, even in a welfare society offering high-quality care to all pregnant women (Reid and Meadows-Oliver, 2007). Teenage pregnancy is also linked to preterm birth and babies that are small for gestational age (Gortzak-Uzan et al, 2001). With regard to their own long-term outcomes, teenage mothers have an increased rate of premature mortality, being almost 30% more likely to die from any cause before reaching the age of 50 years than women without children (Webb et al, 2011).

More family conflict, fewer social supports and low self-esteem have all been associated with increased rates of depressive symptoms in adolescent mothers during the first postpartum year (Reid and Meadows-Oliver, 2007). The Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) programme continues to develop nationally to support teenage mothers and has been shown to have an impact on maternal health, antenatal care and breastfeeding rates (FNP National Unit, 2012). However, it is not available in all geographical areas and not all teenage mothers are eligible for the programme. In the authors' district general hospital, the care of teenage mothers has historically been shared between community midwives and a consultant obstetrician with a special interest in teenage mothers. However, as discussed, teenage mothers need additional support, which the community midwives struggle to provide due to high caseloads. In addition, teenage mothers may feel uncomfortable using antenatal services, leading to a high non-attendance rate, which has an impact on both their wellbeing and health-care resources (Fraser et al, 1995; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2010). A high non-attendance rate at the consultant obstetrician's antenatal clinic had been observed locally.

Research indicates improved outcomes with a dedicated antenatal service for teenagers (Ukil and Esen, 2002; NICE, 2010). A teenage antenatal service—with tailored antenatal education, continuity of care with a named midwife and named obstetrician, and postnatal home visits and clinics to discuss contraception—may be useful in this group of patients (DCSF, 2007). These interventions may have an impact on the teenage mother's experience of antenatal care, improve obstetric outcomes and increase appointment attendance rates, breastfeeding rates and the uptake of postnatal contraception (Das et al, 2007).

Project development

As part of a Health Education England Kent, Surrey and Sussex grant, a service development project was implemented, aiming to evaluate the impact of having a named midwife for teenagers to improve local services for teenage mothers. This included development of a tailored teenage antenatal service for women aged ≤ 19 years. It comprised a dedicated midwife-led teenage antenatal clinic, antenatal and postnatal home visits and tailored antenatal education (individual or group).

Implementation of the service development project

The project was piloted at a district general hospital in February–August 2014; during this period, 31 teenagers gave birth. A Teenage Antenatal Care Pathway was already in place in the hospital prior to implementation of the project; minor changes were made to the pathway as part of this intervention. To support early identification of risk and social need of each teenage mother, a referral proforma was put in place (Table 1).

| Level of need | High | Intermediate | Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 16 and under | 17 | 18–19 |

| Mental health issues | Currently under CAMHS/any severe mental health concerns | Mild–moderate mental health concerns | None |

| Risk from others, domestic abuse | Domestic abuse in current living situation | Domestic abuse from ex-partner | None |

| Offending behaviour | Actively offending/on probation/under youth outreach team | None | |

| Safeguarding concerns | Open case with children's services | None | |

| Housing status | Homeless/living in refuge | Not in an ideal housing environment | Stable housing environment |

| Social support | None | Good family and/or partner support | |

| Disability | Severe disability that will impact parenting | Mild–moderate disability that may affect parenting | None, or disability that will not affect parenting |

| Substance misuse | Ongoing substance misuse/in the recent past | In the past | None |

| Child in care? | Child in care/care leaver (allocated to 16+ team) | No | |

| Participation in learning, education or employment | Not engaging with employment or education | Remaining in education | Full-time employment |

CAMHS–child and adolescent mental health services

Antenatal education

Increased health inequalities in teenagers (such as poor diet or smoking) have been shown to have an impact on increased rates of infant mortality, low birth weight and premature birth (Department for Education and Skills, 2006; PHE et al, 2015). A teenage health education pack was distributed to the teenage mothers during antenatal clinics; the pack supported health education discussions and included information about diet, smoking, breastfeeding and promoting healthy living.

A tailored antenatal class was relaunched to educate young parents about labour and birth, and prepare them for parenthood. Individual antenatal education was also offered for those who may prefer to have one-to-one antenatal education at a location of their choice, in line with guidance from PHE et al (2015).

Antenatal clinic

A midwife-led antenatal clinic was introduced, alongside the teenage specialist obstetrician. The aim was to see every identified high-risk teenager and implement a clear obstetric plan for their pregnancy. The named midwife for teenagers would then provide all antenatal care for those in a higher social risk category.

Analysis of service outcomes

A medical record audit was carried out before and after the intervention, to assess whether the intervention had changed the experience of the teenage expectant mothers, obstetric outcomes and appointment attendance (Table 2).

| Number of appointments attended |

| Chlamydia screening |

| Parent education class offered |

| Referral to a children's centre for support offered |

| Information package given |

| Intention to feed (breast or formula) |

| Birth weight |

| Gestation at birth |

| Obstetric outcome (whether assisted or not) |

| Rate of induction of labour |

| Number of teenagers accessing the tailored antenatal class |

The project included information on 31 pregnancies of teenage mothers aged ≤ 19 years who gave birth during the period February–August 2014. Data from this group were compared to 52 teenage mothers who received care under the previous care pathway (who gave birth in the period February–August 2013) and also to the general population giving birth at the District General Hospital.

Qualitative feedback from the teenage mothers was collected after each tailored antenatal class via an anonymous questionnaire; verbal feedback was also welcomed throughout their care. An anonymous questionnaire was sent to 126 midwives working in the Trust to investigate whether the role of named midwife for teenagers had affected their workload, whether staff adherence to the Teenage Antenatal Care Pathway had improved and whether the midwives valued having a dedicated midwife for teenagers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between subjects and controls were evaluated. Chi-squared tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to investigate whether distributions of categorical variables differed from one another. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Confidence intervals (CI) were evaluated at 95%.

Findings

The Teenage Antenatal Care Pathway

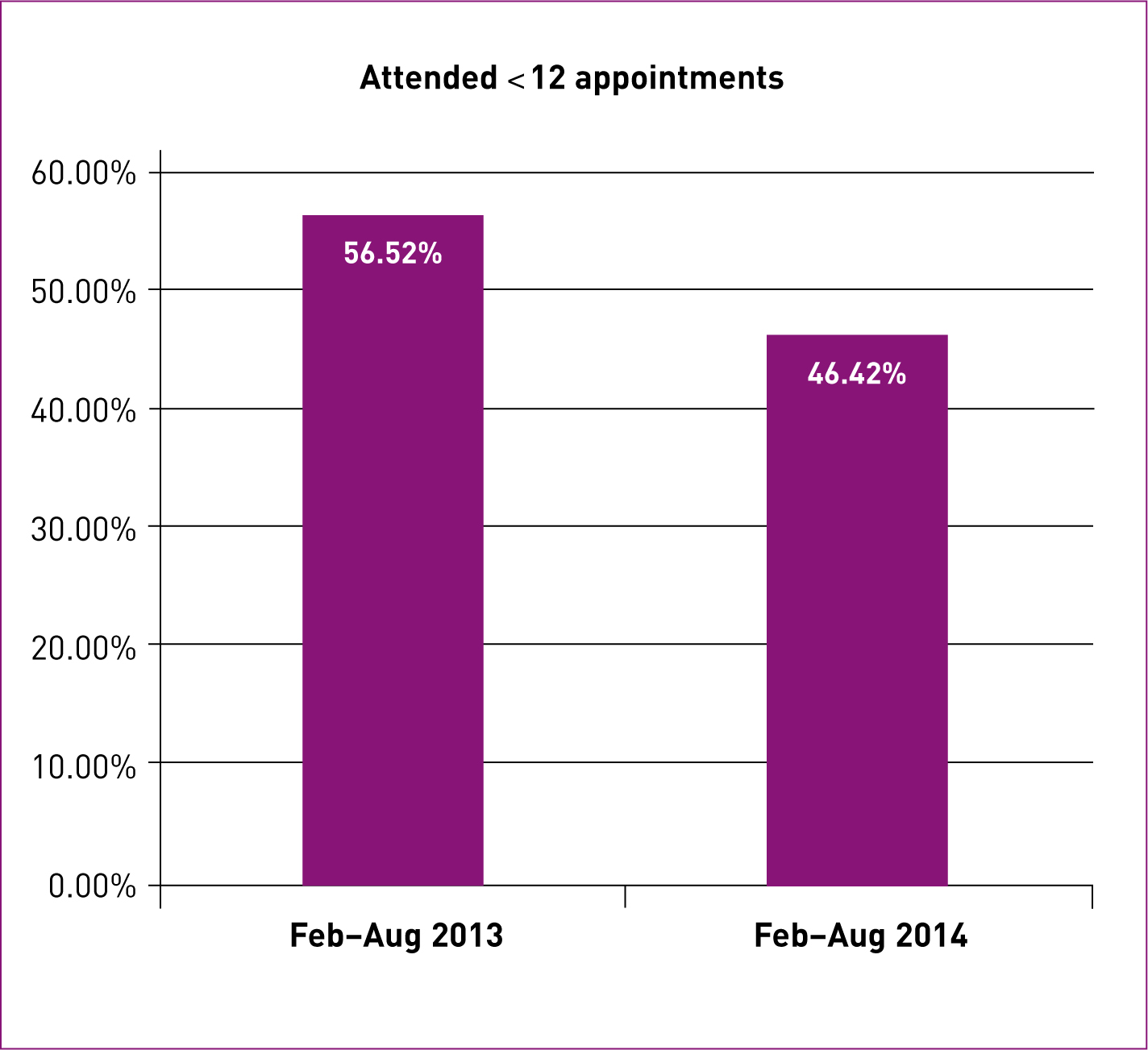

All teenage mothers' medical records were audited to establish whether the intervention had improved adherence to the pathway. The numbers showed a statistical difference in teenage-specific information being given to teenage mothers, antenatal classes and children's centre offer. The audit showed an increase in chlamydia screening, but this was of no statistical difference (Table 3). The percentage of teenagers who attended fewer than the recommended 12 appointments, although not statistically different (P = 0.399), did decrease slightly during the project (46.42% in 2014 compared to 56.52% in 2013) (Figure 1).

| Feb–Aug 2013 (n = 52) | Feb–Aug 2014 (n = 31) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Chlamydia screening | 20 | 38.46 | 18 | 58.06 | 0.082 |

| Antenatal class offered | 18 | 34.62 | 26 | 83.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Children's centre offered | 9 | 17.31 | 15 | 48.39 | 0.002 |

| Information pack given | 6 | 11.54 | 22 | 70.97 | < 0.0001 |

| Unable to obtain information | 6 | 11.54 | 3 | 9.68 | – |

Antenatal classes

Although 83.87% of teenage mothers were offered antenatal classes, attendance was poor, at less than 10%. Individual antenatal education was also offered.

Obstetric outcomes

Obstetric outcomes were evaluated before and after the intervention. Although no statistical difference was noted (P = 0.383), the audit did observe an increase in the rate of spontaneous vaginal deliveries (SVD) (61.54% to 70.97%) and a decrease in instrumental delivery rate (23.08% to 9.68%). The caesarean section rate increased slightly (15.38% to 19.35%), but remained lower than in the general population. The induction of labour (IOL) rate increased (40.38% to 54.84%); this was already markedly higher in teenagers than the general population before the intervention (Table 4). The majority of IOLs were performed for reduced fetal movements, pregnancy-induced hypertension/pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. IOLs for intrauterine growth restriction in teenage mothers dropped from 32% to 11% during the intervention.

| General population | Teenagers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb–Aug 2013 | Feb–Aug 2014 | Feb–Aug 2013 | Feb–Aug 2014 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total births | 1816 | 100 | 1851 | 100 | 52 | 100 | 31 | 100 |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 1077 | 59.31 | 1054 | 56.94 | 32 | 61.54 | 22 | 70.97 |

| P value between 2013 and 2014 | 0.147 | 0.383 | ||||||

| Instrumental | 306 | 16.85 | 328 | 17.72 | 12 | 23.08 | 3 | 9.68 |

| Lower segment caesarean section | 433 | 23.84 | 469 | 25.34 | 8 | 15.38 | 6 | 19.35 |

| Induction of labour | 477 | 26.27 | 458 | 24.74 | 21 | 40.38 | 17 | 54.84 |

There was no significant difference in the average gestation at delivery: 39 weeks + 2 days for teenagers in 2013 compared to 39 weeks + 3 days in 2014.

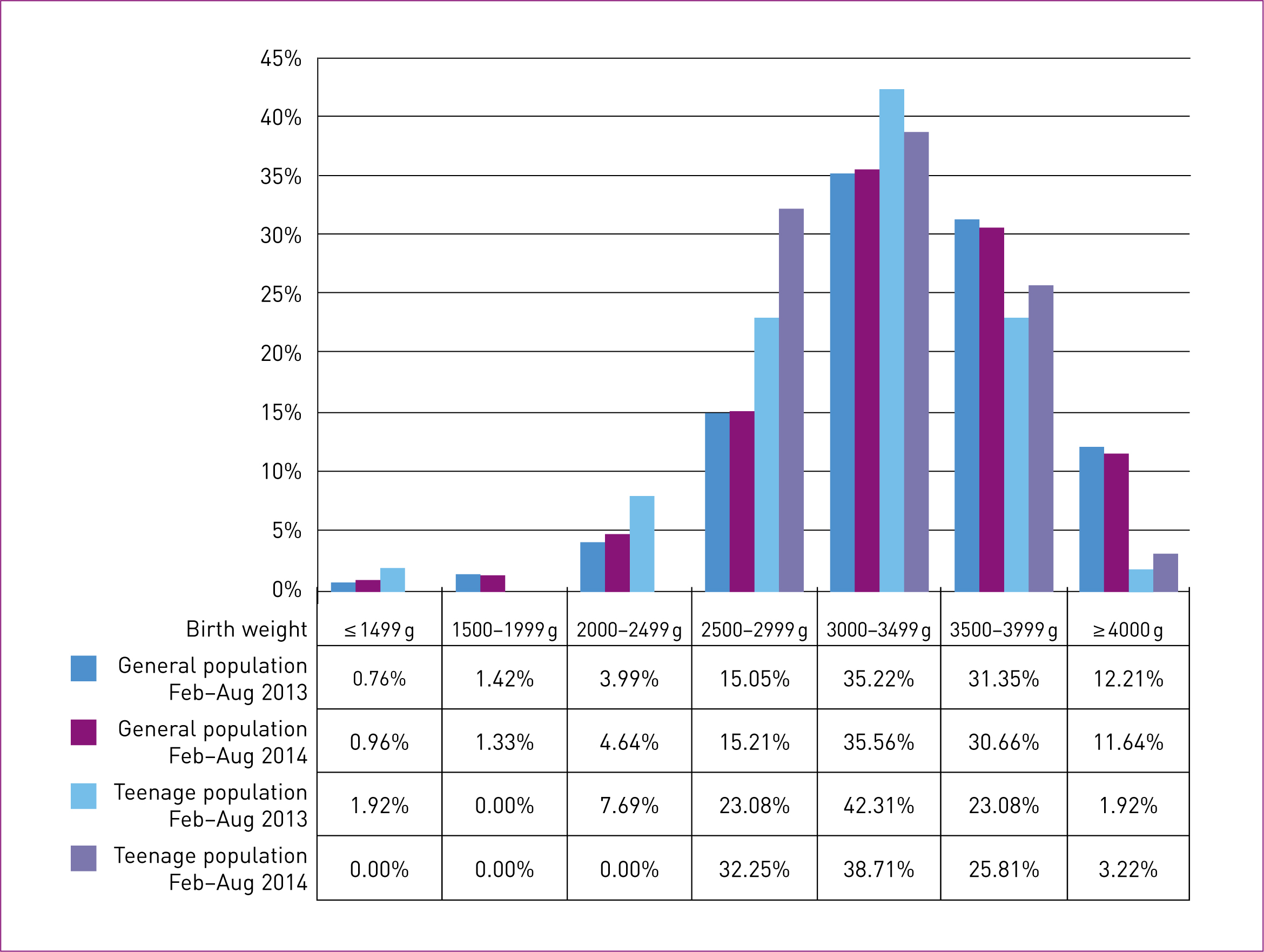

The birth weight of babies born to teenagers was evaluated and compared to the general population and to teenagers before the intervention (Figure 2). Overall, the birth weight of babies born to teenage mothers was lower than the weight of babies born to mothers aged ≥ 20 years. However, there was an increase in the birth weight of babies born to teenage mothers in 2014 compared with 2013.

The audit showed an increase in teenagers intending to breastfeed following the intervention, from 50% to 58%, although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.476) (Table 5).

| General population | Teenagers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb–Aug 2013 | Feb–Aug 2014 | Feb–Aug 2013 | Feb–Aug 2014 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Bottle feeding | 194 | 10.68 | 228 | 12.24 | 26 | 50.00 | 13 | 41.94 |

| Breastfeeding | 1592 | 87.67 | 1583 | 85.02 | 26 | 50.00 | 18 | 58.06 |

| Mixed feeding | 30 | 1.65 | 51 | 2.74 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1816 | 100 | 1862 | 100 | 52 | 100 | 31 | 100 |

The audit results overall show a trend of improvement in outcomes. Given the small sample size, this was not statistically significant but is clinically relevant in showing how changes in service can alter behaviour and uptake.

Feedback from teenage mothers

Only two teenage mothers attended the antenatal classes, but positive feedback was obtained from some of the teenage mothers in the antenatal clinic. Verbal reports highlighted the importance of seeing the same person throughout their care, whom they felt able to trust. One of the teenage mothers said:

‘Learning how to feed, change and bath a baby was really helpful to us as we didn't know and the other antenatal class we went to didn't help.’

Feedback from midwives

An anonymous staff questionnaire was used to obtain feedback. Of 126 midwives to whom the questionnaire was sent, 16 (12.70%) responded. The questions asked were all open-ended qualitative questions (Table 6).

| Caseloading ‘ | The role has made less work for the named midwife and appointments/follow-ups have been arranged by the teenage specialist midwife’ |

| ‘I have valued our mutual clients having a dedicated contact who has more visiting/appointment flexibility’ | |

| ‘[I have found it] valuable as I know that all follow-up and safeguarding involved is reviewed and documented’ | |

| Midwife-led antenatal clinic | ‘On days of a very busy clinic, the role is invaluable as it gives time for these teenagers which might not otherwise be available’ |

| ‘When I have seen teenagers in ANC [antenatal care], they really value the work done and the continuity given to them is excellent’ | |

| Antenatal education | ‘They are better prepared in labour and for how they want to parent’ |

| ‘It has made a massive difference seeing them come in prepared for labour, understanding what will happen, their pain relief choices and feeding options, more want to try to breastfeed’ | |

| Communication with patients | ‘Your expertise and the way you are able to communicate with young mums. I feel that without your input those mums sometimes get lost in the system’ |

| ‘I feel it is really important to the teenagers to have someone they trust and confide in and who can prepare them as much as possible, in a way they take note of without feeling patronised or judged’ |

Costings

The main cost of implementing this project was the employment of a named midwife for teenagers on a 15 hours/week contract (band 6). The role had a positive impact on releasing time capacity for the consultant and a safeguarding midwife (band 7) who had previously run the clinic; this was now run by a band 6 midwife alone. The safeguarding midwife was able to handover all teenage cases, having previously been required to provide safeguarding care and group antenatal education for teenagers.

Discussion

This service development project highlighted the benefits of a tailored teenage antenatal service in improving obstetric outcomes. Although not statically significant, the outcomes were clinically important in increasing engagement with antenatal services and midwifery care. The tailored antenatal service comprised a midwife-led teenage antenatal clinic, antenatal and postnatal home visits and tailored antenatal education.

Improved adherence to the antenatal pathway was highlighted in the appointment attendance rate. Local Trust guidelines recommend 12 appointments for teenage pregnancy within the Teenage Antenatal Care Pathway in view of teenagers' tendency towards poorer obstetric outcomes. NICE (2010) recommends that teenage mothers would benefit from a specialised service offering individualised care. Teenagers are also known to not always engage well with antenatal services; there is evidence that they do not always prioritise appointments, or may have difficulty in accessing them (PHE et al, 2015). In this study pilot, we saw an increased trend in the percentage of teenage mothers attending 12 appointments; this may be due to continuity of care and closer monitoring of appointments.

The service development also had an impact on the increase in the delivery of teenage-specific information to teenage mothers via the teenage information packs and antenatal appointments. These results should be considered, not only in relation to obstetric outcomes, but in light of the importance of early intervention in improving long-term childhood outcomes (Allen, 2011). Starting interventions in the antenatal period has a positive impact on the baby's development, particularly in relation to the brain. A fetus or baby exposed to stress can have its responses to stress (cortisol) distorted in later life (Leadsom et al, 2013). The antenatal period is important in preparing for parenthood to support attachment and reduce factors that may have an impact on this e.g. postnatal depression. Hence, parental education can help improve postnatal outcomes. Further evaluation of teenagers' poor attendance at antenatal classes should be undertaken.

Rates of SVD are higher, and rates of instrumental births tends to be lower, in teenage mothers than in older women (Derme et al, 2013), as shown in the teenage population at this district general hospital. During the project, a positive increase in the rate of SVD was observed, along with a decrease in the instrumental birth rate in teenage mothers in 2014 compared to 2013.

Although there was an increase in IOL, the data showed a reduction in the rate of IOL for intrauterine growth restriction in the teenage mother group (down from 32% in 2013 to 11% in 2014). Being a teenage mother has been associated with small-for-gestational-age babies (Chen at al, 2007). However, adequate antenatal care can be a protective factor against very low birth-weight babies in women < 20 years of age (Xaverius et al, 2016). It has also been shown to improve health education and reduce maternal health complications and premature births.

Positive outcomes for teenage mothers could be linked to continuity of care. In a systematic review of the literature, Sandall et al (2015) identified that midwife-led continuity of care led to a higher probability of women being less likely to experience interventions such as instrumental birth, have an increase in SVD and be more likely to be satisfied with their care. However, midwife-led continuity of care has not been shown to have an impact on the number of caesarean births; this project showed a slight increase in the caesarean rate for teenage mothers.

National statistics for breastfeeding in teenage mothers are currently unavailable, although it is known that the number of teenage mothers intending to breastfeed is significantly lower than in the general population (McAndrew et al, 2012). This project gathered data on feeding intention to observe whether there would be an increase in intention to breastfeed as a result of tailored antenatal education and continuity of care. The data showed an increase towards breastfeeding during the project; perinatal intention to feed can be a strong predictor of breastfeeding duration and intensity (Stuebe and Bonuck, 2011). It would be beneficial to also measure breastfeeding initiation and duration rates if implementing a similar project.

Midwives' feedback highlighted time-saving for community and antenatal clinic midwives as well as improvements in preparing pregnant teenagers for labour. However, there may have been a bias towards a positive response, as the midwives were aware that the dedicated midwife for teenagers would be receiving the responses. Another limitation to the questionnaire feedback was the poor response rate. Web-based surveys generally have a lower response rate than other survey methods, such as mail or telephone surveys (Fan and Yan, 2010); to increase the response rate, factors such as timing, computer skills and incentives should be considered. The low response rate for this survey may have been partly due to the questionnaire being sent out during the summer holidays, which is the service's busiest time on account of an increase in workload and annual leave.

Although the percentage of teenagers attending 12 antenatal appointments increased, an ongoing challenge of this project was engaging the teenagers with their antenatal care. They often did not attend appointments without a reminder from a health professional. In order to tackle missed appointments, the hospital now sends text messages to those who consent, reminding them of their appointment. The named midwife for teenagers sent another reminder the day before the appointment. The use of text reminders has worked for those seen solely by the named midwife for teenagers, perhaps due to an ongoing relationship, but has not worked as effectively for other groups.

Another challenge has been obtaining more formal feedback from the teenagers; this has been limited due to poor attendance at antenatal classes. In order to fully evaluate the service, patient experience is crucial and would be significant in continuing the service and promoting the need for it in other Trusts.

The key limitation of this project was the low sample number and lack of comparators. In order to implement a similar project in other Trusts, a longer evaluation period is needed as 6 months only enabled the highlighting of trends. A year-long project would potentially enable other Trusts to assess a larger sample in order to evaluate the significance in data. However, the project has highlighted that a dedicated midwife allows focus on teenage-specific information.

Conclusion

This service development project indicates that the role of a named midwife for teenagers is valuable as the data showed improvement in a number of birth-related outcomes for teenage mothers. This project also highlights the ongoing importance of continuity of care for all women showing positive outcomes, as previous research has demonstrated (Sandall et al, 2015). The results for this type of service need further investigation due to the limited number of teenage mothers and lack of controlled comparators in this audit. If data capture was undertaken for a longer period and larger numbers of teenagers were included, the results may be sufficient to show positive benefit. An additional element to the intervention could include postnatal home visits and/or clinics to provide contraception in order to prevent repeated teen pregnancies.

Key Points

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflict of interest.