Breast milk is remarkable in its ability to match infant needs, providing a complete nutritional profile that adapts in synchrony with infant maturation (Riordan and Wambach, 2010). The World Health Organization (2023) recommends exclusive breastfeeding from birth for at least 6 months and encourages continuation of non-exclusive breastfeeding for up to 2 years. These recommendations are based on the numerous advantages of breast milk for the child, including enhancing the infant immune response, reducing the chance of allergies, such as eczema or asthma (van Odijk et al, 2003; Quigley et al, 2016), as well as for maternal health, reducing the risk of breast cancer and developing type 2 diabetes postpartum (Britt et al, 2007; Gunderson et al, 2015).

Despite the numerous advantages of breastfeeding, the World Health Organization (2023) breastfeeding recommendations do not reflect the current state of breastfeeding in the UK. In 2016, around 80% of mothers in the UK initiated breastfeeding, yet only 44% of these continued breastfeeding at 2 months (Public Health England, 2017). Rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months are as low as 1% (Nicholson and Hayward, 2021).

Hauck et al (2010) found that, in a Western Australian sample of mothers, early cessation of breastfeeding was caused by insufficient milk supply, infant-related reasons (such as an unsettled baby), discomfort and emotional distress. A more recent study in the UK identified that attitudes towards breastfeeding, the availability of information about breastfeeding difficulties and maternal mental health have an impact on cessation of breastfeeding (Norman et al, 2022).

A birth that seems routine to those in the delivery room could be a traumatising experience for the mother. Studies have suggested that approximately one third of birthing people experience a traumatic birth (Baptie et al, 2020; Delicate et al, 2022). According to diagnostic criteria, childbirth becomes traumatic when the mother fears that her life, or that of her infant, is under threat or there is actual harm (Harris and Ayers, 2012). More recent research has highlighted that the objective factors that are often considered when assessing a birth as being ‘traumatic’ are often mediated by women's own subjective experience of the birthing event (Baptie et al, 2020; 2021).

Beck and Watson (2008) conducted a qualitative analysis with women who had experienced what they saw as a traumatic birth. Women identified that in some instances, breastfeeding following birth could be beneficial for the mother, as it allowed women to prove themselves as a mother after a previous sense of failure, enabled women to overcome the traumatic birth by building a secure attachment relationship and helped the mother heal mentally after the traumatic birth by giving her a positive focus. Women in the study also identified situations where breastfeeding could exacerbate previous trauma symptoms. This was associated with breastfeeding feeling like a further violation, exacerbating the pain previously experienced during birth, being compromised by insufficient milk supply, triggering flashbacks of the birth and establishment being hindered by poor attachment to the infant. These findings were also echoed in a larger UK study (Norman et al, 2022).

This study looked to expand on previous studies and understand the lived experiences of women who experienced a traumatic birth and went on to attempt breastfeeding. This was done using a subjective self-reported measure of ‘traumatic birth’ rather than defining trauma based on objective measures.

Methods

This study used a qualitative approach to investigation in order to elicit rich experiential information from participants.

Participants

The study recruited a convenience sample of participants through social media posts on Facebook in relevant support groups, as well as through a mailing list of women who had previously taken part in breastfeeding research. To be included, all participants had to be resident in the UK, over 18 years old and have experienced a self-reported traumatic birthing experience in the UK within the 7 years prior to data collection. The research team were approached by 83 interested participants. Of these, 19 consented to take part. The terms mother and women are used throughout this paper as all participants identified as women and referred to themselves as mothers.

Data collection

Data were collected between January 2018 and April 2019. Participants took part in semi-structured telephone-based interviews that lasted between 17 minutes and 1 hour and 25 minutes. Interviews were arranged at a time convenient to the participants and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. A semi-structured interview guide was produced based on the questions asked in Beck and Watson's (2008) study. The guide was trialled with two participants prior to formal data collection to ensure its validity. Questions encompassed information about their birth, support provided and the breastfeeding experience. Before the interview, participants also completed the impact of event scale (Sundin and Horowitz, 2002) to provide a more objective measure of trauma. These data were not intended for analysis but to support the self-reported traumatic birth participants had experienced.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using reflective thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2012). The six-stage approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006) involved the interviewers familiarising themselves with the data through reading and rereading the transcripts. Potentially relevant information was identified and given meaningful codes. Codes that overlapped or clustered around similar features were grouped into themes and subthemes, which were reviewed and changes were made. Following these stages, the interviewers compared their analyses and made changes to ensure the integrity and trustworthiness of the data. The final analyses were reviewed by another member of the research team.

Ethical considerations

Participants were given an information sheet and asked to provide informed consent over email before arranging of the telephone interview. Ethical approval was sought and obtained through the University of Plymouth School of Psychology ethics committee (reference: 2017-MF/BA_102).

Results

All participants were residents in the UK (nine from the southwest, six from the southeast, two from the north, one from the northeast and one from Northern Ireland), and had experienced a self-reported traumatic birth within 7 years of data collection. Participants were 24–42 years old and the average age was 32.7 years. All participants identified as White, with 18 reporting their ethnicity as White-British and one as White-Irish. The majority (n=16) of the participants were in full-time employment at the time of interview.

Participants' length of labour varied considerably. Four had emergency caesarean sections before labour began and others ranged from 2 hours to a reported 2.5 weeks. Breastfeeding length also varied from <1 day to 24 months, with seven participants still breastfeeding at the time of interview (Table 1). Three had been given a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

| Participant | Length of labour (hours) | Length of breastfeeding (months) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 12 |

| 2 | 0 | Still breastfeeding |

| 3 | 2 | Still breastfeeding |

| 4 | 9 | 12 |

| 5 | 14 | 19 |

| 6 | 12 | 3 days |

| 7 | 5 | Still breastfeeding |

| 8 | 13 | 24 |

| 9 | 0 | 2 |

| 10 | 2.5 weeks | 6 |

| 11 | 12 | Still breastfeeding |

| 12 | 36 | 13 |

| 13 | 6 | Still breastfeeding |

| 14 | 13 | 4 |

| 15 | 0 | 6 |

| 16 | 3 | 3 |

| 17 | 4 | Still breastfeeding |

| 18 | 7 | Still breastfeeding |

| 19 | 0 | 12 |

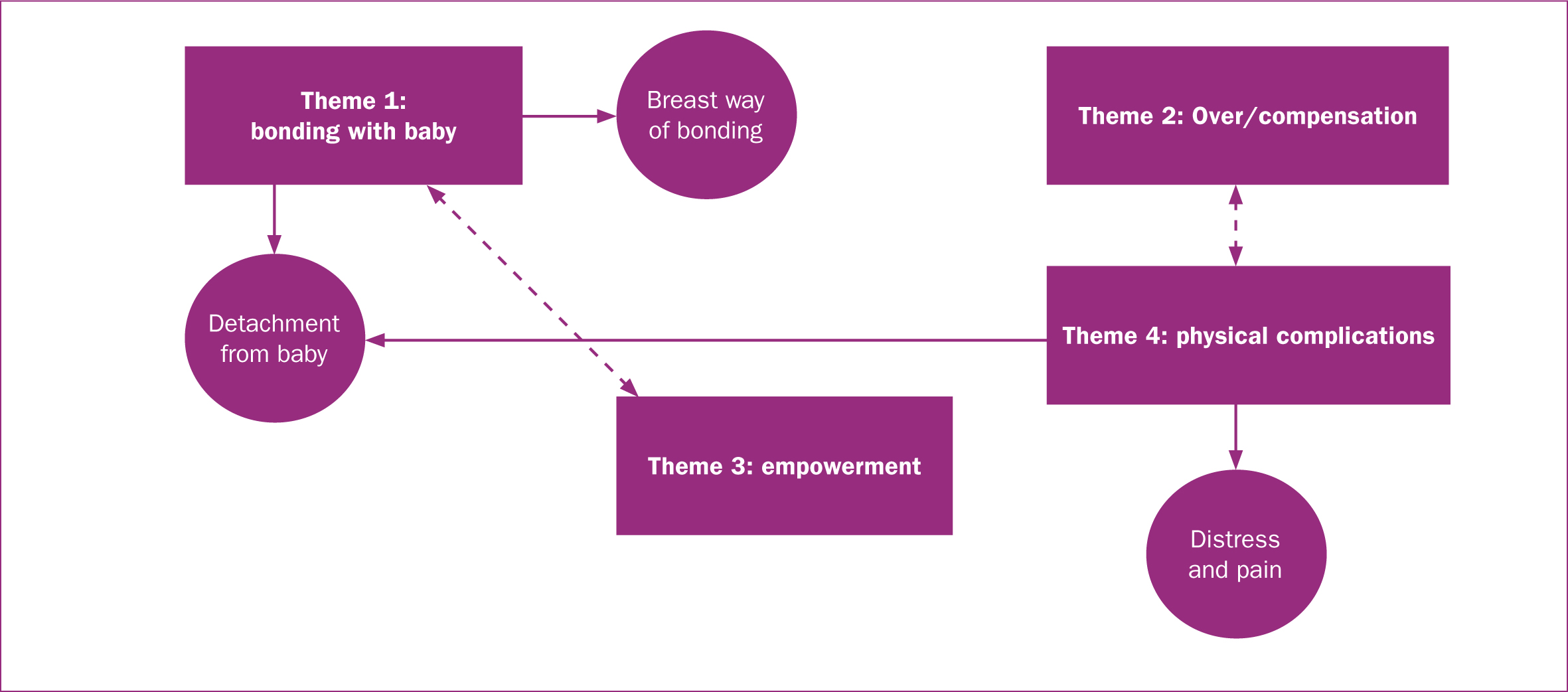

The participants talked at length about their experiences of traumatic births. Although this was not the focus of the study, the findings are briefly summarised to provide context to breastfeeding experiences. Five main themes surrounding birth trauma were identified and are outlined in Table 2. These experiences led to a range of emotional and psychological distress, including being tearful, having heightened emotions, low mood, difficulties making decisions, impaired memory of the birth, a sense of feeling ‘shell-shocked’ and in some cases developing post-traumatic stress disorder. In relation to breastfeeding after a traumatic birth, four themes emerged (Figure 1): bonding with baby, over/compensation, empowerment and physical complications.

| Theme | Explanation |

|---|---|

| ‘Not the birth I wanted’ | Encapsulated sense of distress when birth plans or expectations of birth were not met as a result of sudden changes of plan or use of intervention or monitoring that had not been intended and was intrusive |

| Distress and difficulty | Described the trauma of events themselves |

| Concern for baby | An area of trauma was sense of feeling concerned about the wellbeing of unborn infant |

| Lack of control | Feeling like they were not consulted or in control during the birthing experience led to significant feelings of trauma |

| ‘I'm a mother, get me out of here’ | Experience of being on a ward after birth exacerbated sense of trauma because of feelings of being ‘trapped’ in a hot, noisy, environment with limited sense of control |

Bonding with baby

Participants talked about their experiences of bonding with their infant after a traumatic birth. It was clear from these narratives that, in some cases, breastfeeding helped to heal the lack of bonding from the traumatic labour, but in others it led to a greater sense of detachment from their infant.

Breast way of bonding

Some mothers expressed how breastfeeding was able to heal some of the distance that the birth trauma had caused and brought a much-needed sense of closeness with their infant.

‘Well, I tried so hard, and I know she had found her way out and she was fine, so it made it stronger when I fed her … we were one’.

‘The bonding. It was the breastfeeding that made the difference’.

‘I just found it was the biggest way of actually bonding with her’.

‘It was really kind of a bonding thing and it was just quiet and cuddly’.

Detachment from baby

While some experienced improved bonding through breastfeeding, this was not the experience for all participants. Detachment was experienced in a variety of ways, either because of the time delay between birth and being able to see their infant or because mothers experienced symptoms of trauma post-birth that prevented them from making a connection with their infant.

‘I didn't see him, I wasn't the first person to feed him … I had not bonded with him at all’.

‘You find yourself saying to them, “I know I love you”, but you don't feel it’.

‘I had a friend [who had a caesarean section under general anaesthetic] and she found it really hard to bond with the baby’.

‘In terms of bonding I think I was in shock for couple of days … I didn't feel this immediate protective bond over him’.

‘At the time I kept going quite well, but subsequently over the course of a year once breastfeeding was established, I clearly wasn't bonded. I suspect it was due to my poor physical and mental state after the birth’.

Over/compensation

The impact of a traumatic birth led many mothers to view breastfeeding as a way of ‘compensating’ for what they felt was a ‘failure’ around the birthing experience. For some, it heightened their natural maternal instincts, which provided a sense of purpose around breastfeeding and a desire to succeed despite complications. In these circumstances, the traumatic birth led to increased determination. For some, the ability to successfully breastfeed their baby acted as a protective factor that allowed them to heal psychologically from the distress of the birthing experience.

‘[The birth] made me more determined, I think, to breastfeed, because of everything that had happened’.

‘It was like I had dug my line in the sand, and I planted my feet there and I was going to do this’.

‘I hadn't had a natural birth like I wanted, I was really poorly, couldn't look after me … but actually the support from my midwife of “your baby's healthy if they're fed”, “don't starve your baby and you're kind of doing all right” was the only reason that I kept feeding’.

For others, there was a sense that it led to an unhealthy desire to breastfeed at all costs, with potentially serious psychological consequences for the mothers. This was often tied with the idea of ‘failure’, that mothers felt having had a traumatic birth was somehow their fault. This was further exacerbated in women who had experienced difficult pregnancies followed by a traumatic birth.

‘Because I'd failed [at giving birth] I became so bound up in … I couldn't fail it, I just could not fail at breastfeeding’.

‘I had failed in everything else, I had failed in carrying her safely and I had failed in giving birth to her and this was the one thing I could do and not fail her’.

‘I felt like I'd failed, so I was adamant that I would feed. I was so determined that I wasn't going to fail at that as well’.

‘I felt suicidal at points, in fact I spent quite a few years feeling suicidal’.

Empowerment

Participants talked about breastfeeding being an ‘empowering’ experience. Some participants found that it gave them a sense of pride as a mother and this became part of their self-identity; they became closely connected with the construct of motherhood. Furthermore, breastfeeding allowed participants to regain control and reconnect with their body after losing their sense of autonomy during the birth. One woman described breastfeeding as ‘liberating’. Doing something so natural helped them feel like a mother and had a positive influence on the mother's self-esteem and self-confidence. This was particularly important for some mothers who had felt like a failure during their birthing experience. This was not the experience for those in the study who did not manage to maintain successful breastfeeding long term.

‘I took pride in the fact that I was able to feed him’.

‘The confidence knowing that, you know, you're the person keeping … him fed’.

‘When she consistently breastfed it was just the most positive thing on this planet’.

Physical complications

Participants discussed at length the physical complications that made the process of breastfeeding difficult for them. There was a feeling that many of the issues they faced were exacerbated by the traumatic birth experience.

‘I had a really poor let-down. He's a really hungry baby’.

‘He struggled to latch on’.

‘I don't think [the paediatric nurses] appreciated that I needed to express because she wouldn't feed’.

‘There was no one to help. It wasn't their fault … it was understaffed and they were stretched’.

There was a sense that either because of the reasons for the traumatic birth or because of the physical harm caused to the mother or baby, they often struggled to breastfeed successfully. Participants felt this was often not considered by the healthcare professionals around them.

‘She was so tiny. She just looked at [my breast] like what is that? That's not fitting in my mouth’.

‘I don't think I could have done it [without my husband] because I physically was so incapacitated’.

‘I was really poorly, couldn't look after me’.

‘She was very tired obviously, because she had had the diamorphine as well, through the placenta’.

‘He was really tired all the time because of the jaundice and just wouldn't stay awake … [the midwives] just kept telling me to feed but I was exhausted’.

‘[Breastfeeding] like the birth really, it's a very different experience for every mother and you know, [healthcare professionals] didn't take into consideration really how hard [breastfeeding] was for me’.

‘There are holes in the net that women can fall through’.

Distress and pain

Participants reported significant experiences of distress and pain during breastfeeding, associated with the physical complications of the birthing experience. The participants felt that this was exacerbated by their traumatic birth.

‘It was like, wincing and tears, pain when he latched on’.

‘I was hallucinating my way through the feeds’.

‘The pain was excruciating’.

‘A lot of the other midwives, they were very much “you must sit in the chair” … but I couldn't sit up’.

Furthermore, the distress they had experienced during the birth was often re-ignited during difficult feeds, leading to pronounced mental health problems among some participants and disrupting the bonding process for many.

‘It took me a whole lot of time to … process it’.

‘I ended up with such horrendous postnatal depression, really bad’.

Discussion

This study focused on the breastfeeding journey of individuals who had experienced a traumatic birth. One of the key findings was that participants found breastfeeding more challenging because of the emotional and physical complications caused by a traumatic birth. For many participants, these additional challenges were overcome through ‘sheer determination’. For others, the difficulties they experienced either led them to stop breastfeeding earlier than they would have liked or led them to develop a sense of detachment from their baby.

The participants talked about the need for more support with breastfeeding following a traumatic birth and how they felt that healthcare professionals did not allow for the physical and emotional distress they experienced during breastfeeding because of their traumatic birthing experience (Beck and Watson, 2008; Norman et al, 2022). Others discussed practical difficulties they experienced, such as needing to express rather than directly feed their infant or needing to feed lying down because of physical complications for themselves or their infant. In many instances, participants felt that the support was not sufficient to enable them to work through these challenges in the early days and weeks of feeding. This even included poor access to appropriate or sanitary equipment, such as breast pumps in hospital.

While breastfeeding was viewed by some participants as a protective factor that allowed them to bond with their baby after a traumatic birth, and in some instances improved their mental wellbeing, others reported the opposite. For some, breastfeeding exacerbated their feelings of failure and led to poor self-esteem and depression. Participants described having ‘failed’ at birthing their infant appropriately. This was expressed even by participants who went on to develop a strong bond with their baby and reported breastfeeding as a positive experience.

There has been previous reference to the role of the mother and the importance of ‘failure’ for women's mental health in the early stages of being a mother (McGuire, 2016; Keevash et al, 2018; Norman et al, 2022). Many studies have identified the negative impact of the pressure mothers place on themselves to breastfeed and perceived pressure from healthcare professionals (Norman et al, 2022; Scarborough et al, 2022; Thompson et al, 2023). In the present study, many women appeared preoccupied with the construct of the ‘successful’ mother being one who has a natural and uncomplicated birth followed by successful long-term breastfeeding. While this may be the desired goal, this is not the experience of many individuals (Andersen et al, 2012; Milosavlijevic et al, 2016). There is a need for more honest and information about the potential realities of birthing and breastfeeding to help reduce this sense of failure. Further research is required to identify how best to provide such information antenatally in a manner that empowers rather than alarms those who are pregnant.

It is important for healthcare professionals to hold in mind that the relationship between breastfeeding and maternal mental health is complex and while oftentimes positive (Groër, 2005; Krol and Grossmann, 2018; Scarborough et al, 2022), can also have a detrimental impact on women's wellbeing (Scarborough et al, 2022). While encouragement to breastfeed is important for infant health, as well as maternal health (both physical and mental health), it is also important that healthcare professionals work closely with mothers to help them establish and maintain breastfeeding in a supportive and non-judgemental way.

Limitations

This study took a qualitative perspective to understand the experience of those who had breastfed their infant following a traumatic birth. As a result of the nature of the enquiry, the aim was not to ensure generalisability across the UK population. However, the sample shows many of the usual biases seen in other studies of breastfeeding in the UK; the sample consists mainly of White, middle-class, highly educated women who have breastfed for longer periods of time. Therefore, the impact of factors such as social deprivation, social class, ethnicity and education cannot be unpicked. These are undoubtedly likely to influence the experiences of those who are breastfeeding after traumatic birth and therefore need further investigation.

The study did not require participants to provide detailed medical information about their birthing experience, although many mothers did share this with the research team. Therefore, it was not always possible to identify exactly what some of the mothers meant by ‘traumatic’ when referring to their birth. While this may be viewed as a limitation, it is important to note that subjective components of birth have been found to be better predictors of traumatic symptoms postpartum than objective measures (Baptie et al, 2020).

Implications for practice

This study has identified some key areas for consideration in clinical practice. It is important that healthcare professionals recognise the increased vulnerability of individuals who have experienced traumatic births and how this may impact their breastfeeding journey. Greater support, both through guidance and reassurance, is needed for individuals breastfeeding after a traumatic birth. This should include longer-term follow-up support with mental health-related issues in those that show signs of struggling. It is also important that equipment is made available to those who have experienced traumatic births so that they can find solutions to early complications with feeding. Such equipment should include easy access to breast pumps for expressing and support cushions and pillows for comfortable positioning. Finally, it is important that those who have experienced a traumatic birth, whether objectively or subjectively, are able to engage in debriefing to help them to understand what happened during their birth and talk through any negative experiences that may impact breastfeeding.

Conclusions

This study investigated the experiences of mothers who were breastfeeding following a traumatic birth. The study supports previous findings that those who have experienced a traumatic birth often face greater challenges to breastfeeding associated with physical complications, distress and pain. In some instances, this led to a poor breastfeeding experience associated with a sense of detachment from their infant, while for others, breastfeeding was able to mitigate the negative impact of a poor birthing experience and lead to a sense of empowerment. The study highlights that for many individuals, successful, natural birthing and breastfeeding are highly associated with success as a parent, sometimes with a long-term negative impact on mental health.