The healthcare system in Jordan is well developed, and access to healthcare facilities is generally widespread (Ministry of Health [MOH], 2018). Nevertheless, the practice of maternal care in Jordan is still not evidence-based (Khresheh et al, 2009). A previous Jordanian study that examined maternity hospital practices during childbirth and assessed their consistency with evidence-based maternity care practices focused specifically on six practices that were undertaken during labour. These practices were augmentation of labour, continuous electronic fetal monitoring, support in labour, episiotomy, position for birth, and administration of oral fluids during labour (Shaban et al, 2011).

The most important results reported by Shaban et al (2011) were that many of the common childbirth practices that were routinely followed in maternity hospitals in Jordan were not evidence-based. Moreover, not only the beneficial practices were neglected but also the practices of unproven benefit or practices that were potentially harmful were performed. Overall, the study concluded that childbirth practices that were used to assist women in labour were largely inconsistent with the evidence-based practices for normal birth recognised and recommended by the World Health Organization ([WHO], 2018).

The study by Shaban et al (2011) is one of a scant number of studies that have been conducted in Jordan to examine maternal care practices during pregnancy and childbirth according to the universally accepted recommendations on maternal care practices. In another study that was conducted in the Jordanian context, it was reported that the rates for several inappropriate yet routinely practiced labour and birth interventions were high, and differed from the WHO guidelines and evidence-based recommendations (Khresheh et al, 2013). The rates for the augmentation of labour and episiotomy at 46% and 53%, respectively, were particularly high, and seemed to be excessive in comparison to the WHO recommendations, which state that such practices should not be undertaken routinely. Furthermore, it has been reported that the estimated rate of induction is between 15%–20% (Hatamleh et al, 2008). However, there are no reliable statistics to support this assertion, and practicing obstetricians have no official guidelines or policies to follow in respect of the use of induction. Although, induction rates have been declining after decades of consecutive increase (Osterman and Martin, 2014).

Nevertheless, observers agree that the Jordanian government's programmes for addressing obstetric emergencies have contributed to a significant reduction in the number of maternal deaths (Hatamleh et al, 2008). However, there is some evidence to suggest that despite this laudable achievement, Jordan runs the risk of over-medicalising maternal healthcare, which may in part be due to the rapid increase in the use of technology to start, augment, accelerate, regulate and monitor the birth process that has led to the adoption of inadequate, and sometimes unnecessary, interventions that are associated with increased risk. Importantly, there is no clear policy on what constitutes ‘normal’ pregnancy and childbirth, therefore the induction of labour in particular is not monitored nor is it policy led (Hatamleh et al, 2008).

In Jordan, as in some other countries, there may be well-routine overuse of treatments that were originally designed to manage labour and birth-related complications. This implies that many healthy women are being exposed to the side effects of unnecessary interventions. Moreover, evidence-based protocols for maternal care practices are not promoted. Furthermore, the available literature indicates that birth practices in Jordan are interventionist and differ from international guidelines and evidence-based recommendations (Caughey et al, 2009; Okour et al, 2012). Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the reasons for not applying evidence-based practices in maternal care in Jordanian governmental hospitals from the point of view of the healthcare professionals.

Method

It is worth mentioning that this study is the first part of a large project about application of evidence-based practices in maternal care in Jordanian governmental hospitals. The second part of the project is running now.

Design and setting

A descriptive qualitative design was used to achieve the objective of this study. The setting was selected purposefully for this study. It was one governmental hospital in Zarqa Governorate in Jordan. It has a large obstetrics and gynaecological department (including antenatal, labour and postnatal wards). This department provides a variety of healthcare services for pregnant, giving birth and postpartum women. It has 103 beds with an occupancy rate of 75% and approximately a total of 8 094 cases annually of which 5 732 are vaginal deliveries including instrumental deliveries and 2 362 are by caesarean section (MOH, 2018).

Participants

Eleven healthcare professionals in the obstetrics and gynaecological department participated in the study according to the inclusion criteria. Each participant had to be a healthcare provider in the selected department of the selected hospital and have been working in the selected hospital for at least five years. Further, they have to be from all health professions who provided direct care to the women came for labour and delivery (physicians, maternal nurses and midwives). We recruited the head of the department who was an obstetrician providing care and the decision maker in the department in relation to care provided, two other physicians (obstetricians) who were providing direct care and working with other staff, five midwives who were giving direct care during labour and birth, and three maternal nurses working with mothers after birth.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct the study was sought and obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University and from the MOH (2980/ethical committee in 2017). After receiving approval for the study, the researcher contacted potential participants to invite them to take part in the study. All the participants provided written consent indicating their agreement to participate in the study. The information and data collected from the participants were kept confidential and were used for research purposes only. The members of the research team were the only people who dealt with the participants' information.

Recruitment and data collection methods

The researcher, who was a healthcare professional but was not working in the hospital, contacted the potential participants in their working area (face-to-face), and briefed them about the study. Those who were willing to take part were asked to complete an informed consent form before the start of the interview. Semi-structured, in-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted between April and August 2018 using a pre-prepared interview guide (Table 1), and were conducted in a special room at the hospital. The level of data saturation was determined by the primary researcher during the data collection process, when redundancy of information was achieved.

Table 1. Interview guide

| The questions in the interviews with the participants will be grand tour questions to get an in-depth assessment about the research problem of this project |

|---|

|

All the interviews were audio-recorded and the anonymity of participants was maintained by giving them ID numbers. Then transcription of verbatim and translation from Arabic into English were done by the first and second researchers.

Data analysis

The recorded interview data were analysed using thematic and content analysis according to Braun and Clarke's (2006) six steps of analysis. The first step is familiarisation with data: the researchers transcribed the content each of the tape-recorded interviews after carefully listening to the whole recording. Next, all the transcripts were read carefully, then translated to English language by one researcher. The second step is generation of initial codes, such as coding interesting feature across the entire data set. Potential labels were assigned to data segments to describe their contents. Categories and subcategories were generated based on recurrent words or phrases in the data set.

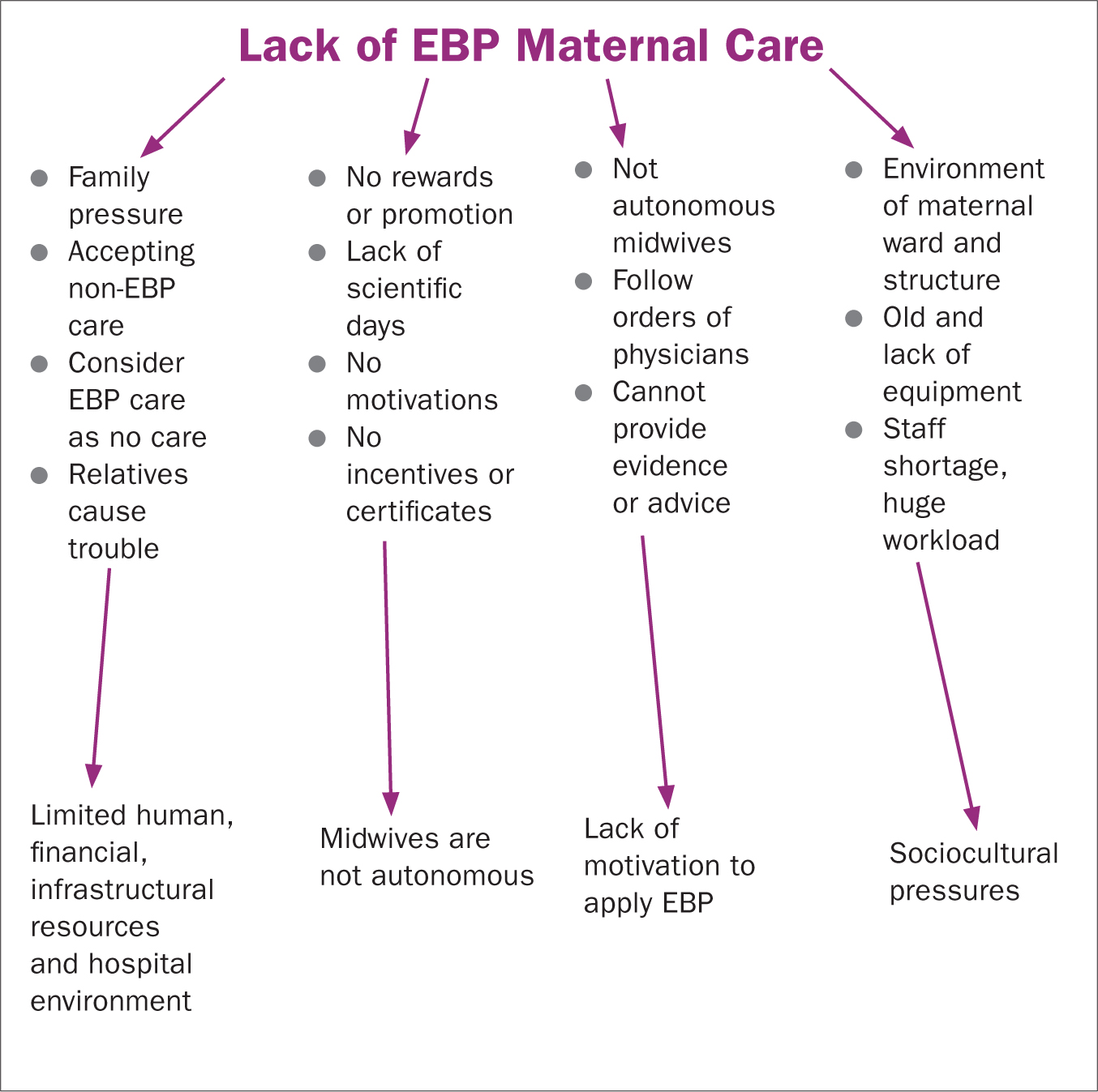

The third step is searching for themes such as collecting codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. So, the data segments were cross-indexed with the original interview transcripts that were re-read and checked against field notes to ascertain the contextual meaning of the data. The fourth step is reviewing themes: generate a thematic ‘map’ (see Figure 1) of the analysis and check the themes' relevance in relation to coded extracts (level 1), and entire data (level 2). The key categories and subcategories together with their appropriate data segments were then organised into meaningful themes, reflecting the aim of the study. The fifth step is defining and naming themes. Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each theme. The second researcher ensured the credibility of this procedure by conducting an independent second analysis of the data. Finally, producing the report. The final opportunity for analysis: selection of rich, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, which are presented in the findings' section.

Figure 1. Thematic map

Figure 1. Thematic map

Findings

The thematic and content analysis of the qualitative interviews in the obstetrics and gynaecological department at selected hospital produced the following four main themes: 1) limited human, financial, infrastructural resources and hospital environment; 2) midwives are not autonomous; 3) lack of motivation to apply evidence-based practices; and 4) sociocultural pressures hinder the usage of new evidence-based practices.

First theme: limited human, financial, infrastructural resources and hospital environment

The first participant, who was an obstetrician and actively participated in the care provided in the ward, gave the research team support and cooperation in the conduct of this study:

Participant 1: ‘We will help you in implementing your project and our staff will cooperate with you to help in improving our job.’

However, he mentioned that the level of cooperation could have been better if there were enough staff (physicians and midwives) in the hospital. This participant also favoured the active management of labour (using medical interventions as labour induction or augmentation) and giving birth in normal and healthy pregnant women rather than applying expectant management (natural process). Although the he acknowledged that there was over-medicalisation in the labour process and while giving birth, he insisted that it was necessary to use active management to deal with the overload in the number of women giving birth at the same time as dealing with a staffing shortage:

Participant 1: ‘We have huge load and a shortage of staff either specialists, physicians or midwives, so we cannot use natural birth as proposed in your project without active management for all cases.’

A similar outlook was evident among the medical staff (physicians and midwives) who were active at the clinical level in the labour room and who cared for pregnant women in labour. It was apparent from the interviews that the routine work in the labour and giving birth unit followed an active management protocol for all the women giving birth, as exemplified by the following two extracts. The first was from the physician, and the second was from midwife:

Participant 2: ‘We use active management to shorten the duration of the first stage of labour to keep extra beds free for other giving birth cases. We do not have enough birthing beds for all birthing women. Using natural birth and new evidence-based practices is time consuming and means that birthing beds are occupied most of the time. Similarly, we do not have enough external monitors and most of the ones we have are not working—we need maintenance for them. We have reported this to the Ministry of Health but routine work and communications channels are taking a long time, so nothing is done, and we have to adapt to the situation.’

Participant 3: ‘The main drawback in the application of any evidence-based practices is the shortage of midwives and equipment, mainly beds. We have only seven beds in the labour room in this huge hospital that serves a large population. It is also a referral hospital in one of the most crowded governorates in Jordan. So we use active management following the physicians' orders to shorten the time it takes for each woman to give birth and to deal with the huge load of women giving birth.’

Another drawback was the infrastructure of the department that was not helpful to apply evidence-based care. Of the participants, nine declared that the building design and layout of the department were not helpful for the practice of evidence-based care. Furthermore, the space in the obstetrics and gynaecological department was not big enough to accommodate the large number of admitted cases because the hospital was also a referral hospital for complicated and high-risk cases. These points are exemplified by the following extract:

Participant 2: ‘It is difficult in governmental hospitals to apply new evidence-based practices in labour rooms because the design of the department is not helpful. If we had one labour room for all the stages of labour then it would be easy to apply evidence-based practices, but here in our hospital as in other governmental hospitals we have special rooms for stage one of labour, another for stage two and three, and another for immediate postpartum care.’

The same complaint was expressed by the midwives too, as shown by the following example:

Participant 5: ‘The design of this unit is not in accordance with requirements because it was established without asking expert staff about their needs in the design stage. It is not helpful for evidence-based care.’

Second theme: midwives are not autonomous

Despite the general acceptance of the practical necessity of applying active management, the midwives expressed some concerns about the approach to maternal care adopted by the department. However, the midwives also stated that they were obliged to follow the physicians' orders. They were not independent actors in respect of providing care and they had no authority to make autonomous decisions. The midwives explained that they executed the physicians' orders even though some of those orders were not in line with evidenced-based practices. Furthermore, as explained by one of the midwives, they were not able to discuss or refuse the doctors' orders, even if they were aware of the evidence-based practice that should be followed:

Participant 4: ‘Midwives only carry out the doctors' orders when applying protocols and policies because midwives do not have any authority, and it is not in their job description to do anything differently. Similarly, midwives cannot give physicians any evidence or knowledge about new practices.’

In addition, as highlighted by another midwife, the midwives might accept the application of evidence-based practices if physicians gave them the orders to do so. However, they might be resistant to any change in practices if it came down to their own personal preferences:

Participant 5: ‘Although midwives accept changes in practice, some of them may need to receive orders from people in authority as the Head of Department or supervisor to implement new procedures and to cooperate. Others may follow the physicians' orders to apply evidence-based practices.’

From the above, it seems that it is established policy that the actions taken by midwives are dependent on the orders given by the physicians and that the midwives are not allowed to apply evidence-based practices even if they have the necessary knowledge and skills to do so.

Third theme: lack of motivation to apply evidence-based practices

The managers of nurses, midwives and physicians (participants who also had administrative responsibilities) said that there had been training to use evidence-based practices by the physicians in the obstetrics and gynaecological department. As mentioned by physicians, the department had guidelines for the management of high-risk cases and complications, such as bleeding, eclampsia and pre-eclampsia, among others:

Participant 2: ‘Our physicians are prepared as they have been given some evidence-based guidelines for high-risk cases and complications in areas such as bleeding management, eclampsia and pre-eclampsia management, and magnesium sulphate administration.’

Furthermore, a nurse in managerial position and a physician described their work environment as a discouraging environment for evidence-based care practices:

Participant 7: ‘The working environment in this department does not provide motivation for the staff.’

Participant 2: ‘There is a lack of motivation among the midwives and medical staff to embrace change starting with the Ministry of Health, and ending with the hospital, which does not encourage the application of the results produced by research studies. The application of any new policy or program should be driven by the Ministry of Health and distributed to all hospitals.’

Unfortunately, midwifery practices have been learned from the previous midwifery generation, not from new evidence-based practice reports. Even newly graduated midwives learned maternal care practices from the senior midwives in the hospital. To develop themselves, they needed incentives such as training courses, compensation, certificates and promotion. This point was highlighted in the following excerpt:

Participants 5: ‘We have been trained by experienced midwives. To build ourselves, we ask for incentives such as training within regular duty days, taking off days as compensation instead of duty days, certificates, and promotion.’

Fourth theme: sociocultural pressures hinder the use of new evidence-based practices

All 11 healthcare professionals in this study stressed that social and cultural pressures hindered them from implementing evidence-based care for women in labour and delivery. Usually, women get their information from their relatives and friends. Unfortunately, they believed that the shorter the time it takes to give birth the better healthcare is provided. They did not accept a long labour or birthing process unless it was a complicated birth, as explained by one of the physicians:

Participants 2: ‘I was on call one night, and I had a primi [gravida] case which took a long time in both labour and giving birth, and after the episiotomy, I kept her under observation in the labour room, but her family members shouted and caused problems because the woman did not leave the labour room immediately.”

From the above example, the relatives of women giving birth who would be waiting outside the labour room might make trouble if the birthing woman took a longer time than they expected in the birth room. Due to the expectation that a fast birth is a normal birth, the family put pressure on pregnant women to refuse the use of the new recommended protocols for labour and birth, and they preferred the active management of labour and birth to shorten the duration of labour.

Participants 3: ‘If a woman in labour is in the labour room for a long time, we get a lot of phone calls or knocks on the main door of the labour room from her relatives asking about her and comparing other cases that have stayed for a shorter time in the labour room with her situation. There is huge pressure from relatives, and their perception that normal vaginal delivery takes a short time makes it difficult to apply evidence-based practices for a natural birth when people have such perceptions.’

Participants 2: ‘We can't keep the labouring woman to give birth naturally because it may take long time, and her relatives will be annoying us and problem makers, it is a social and cultural pressures that prevent us from using evidences in maternal care.’

Moreover, Jordanian women believed that the use of many medical interventions reflects the best care and practice, even though they may complain about the many vaginal examinations and pain killers that are part and parcel of these interventions. According to the participants in this study, most Jordanian women obtained their information about best practice from family members and friends. From their point of view, it seems that the best practice is to ensure a short period of labour without pain, as illustrated in the following extracts:

Participant 8: ‘A labouring woman knows that frequent a PV [per-vaginal] exam (hourly), for example, is good care and that the medical staff are not ignoring her, and this becomes a cultural perspective because this is a routine practice.’

Participants 5: ‘Continuous monitoring is considered one of best care practices according to labouring women.’

In Jordan, because of cultural issues, it is not acceptable at all for a companion to be present in the labour and birth rooms in governmental hospitals as there is no private room for each labouring woman. It is prohibited to have a male partner in the maternity wards, as pointed out by a physician:

Participant 1: ‘In our culture, it is not acceptable that the husband attends the labouring and giving birth process to support his wife, as in western countries. So it is not easy to change this perception.’

It is also worth mentioning that labouring women have to transfer from the labour unit to the birth room. This is another reason for preventing the presence of men in these units. Culturally, and in Islam, other men are not allowed to see other women in such a situation.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the reasons for not applying evidence-based practices in maternal care in Jordanian governmental hospitals from the healthcare professional's perspective. The data collected for this study illuminate the situation from the standpoint of healthcare professional currently working in a maternal care setting as the analysis identified four main themes. First, this study found that the lack of human, financial, infrastructural resources and hospital environment—is a huge obstacle that hampers the implementation of evidence-based practices in the obstetrics and gynaecological ward at the selected hospital. This finding was supported by the findings of a South African study, which found that lack of necessary skills and training, lack of facilities and equipment, and communication difficulties between midwives and women were barriers to the utilisation of alternative birth positions (as evidence-based practice) in labour room (Musie et al, 2019).

Furthermore, in our study, it seems that it is difficult to ask for more resources because the selected hospital is affiliated hospital to the MOH that also has limited resources, personnel and budget. In order to change maternal care practices so that they are in compliance with the recommended evidence-based practices requires multi-dimensional efforts at the highest organisational level (ie the MOH) in order to maintain and preferably improve existing structural factors (Holt et al, 2010). Fostering evidence-based practice is a long-term developmental process within organisations or institutions. Multi-strategies are required to create an evidence-based environment, where nurses generate and answer important questions to guide practice (Newhouse, 2007).

This study also found that the level of staff readiness to change fluctuates between willingness and refusal. This is an important psychological factor that needs to be addressed in order to implement changes that will affect the status quo (Holt et al, 2010). We extracted from the staff that they would be willing to use evidence-based practices in their care for labouring women. However, the conditions around them through their experience made them to be reluctant to use it. It has been argued that readiness to change requires both a willingness and capability to change. However, an organisation filled with individuals that are energised psychologically about an impending innovation but are ill-equipped to accomplish it. So it is no readier than one that is full of individuals who are apathetic but well equipped (Holt et al, 2010).

Physicians have not been felt motivated to change their conventional care practice (active management for normal labour) to an evidence-based form of care because of a lack of obstetricians or a shortage of physicians. The physicians in this study stated that they were overwhelmed by the workload and that this was the reason behind their refusal to change and implement the recommended protocols for labour and birth management. This finding is consistent with those of a study conducted in Lebanon (Alameddine et al, 2015).

We also found that the midwives did not have any autonomy or authority to perform their duties independently. Rather, they were required to follow the physicians' orders in respect of labour and birth, which were usually based on the active management approach. In addition, they too were overloaded because of the limited number of midwives on each shift. It is good to note here that, one of the essential competencies for midwifery practice and midwifes is to act as an autonomous practitioner. Autonomous midwives are the most suitable caregivers for women throughout childbearing. This will keep birth normal, which will promote better childbirth outcomes for women, their newborns and their families (International Confederation of Midwives, 2018). Whenever midwives become autonomous and take their own decision based on best interest of the women, they will challenge obstetrician's orders and change the provision of care. In Jordan, all practicing midwives are registered in the Nurses Association. The Nurses Association is working with midwives in order to change the current practice and policies in hospital based on research's evidence.

In addition, this study found that the midwives were constrained by physicians' orders in terms of the information and knowledge they could apply. In fact, the care that was provided involved the use of many medical interventions that were not in line with evidence-based practice for normal vaginal birth according to the WHO's (2015; 2018) recommendations. Medicalisation and over usage of resources, leading to more pressure and workload on healthcare professionals (Sethi et al, 2019). Our findings are consistent with those reported in an Indonesia-based study that found midwives and nurses' knowledge is not updated according to the updated guidelines for maternal and newborn care (Sethi et al, 2019).

This study also discovered that cultural and social pressures on the medical staff directly hindered the provision of the recommended evidence-based care in the labour and birth units. The participants stated that relatives of women in labour and giving birth create problems or make complaints against the healthcare team if they perceive that the women giving birth are not doing so quickly enough. They might even perform violent behaviours against healthcare professionals if the woman spends too long in labour and birth, or if she complains of pain. Indeed, cultural pressure was a major factor behind most of the ongoing non-evidence-based practices in the labour and birth units, and explained why these practices had not changed or been updated. This pressure also reflects the low level of accurate health information among the Jordanian population, specifically in regard to the best practices for pregnancy and birth. Furthermore, generally, it seems that the public do not realise that the labouring and birthing process is a personal experience that differs from one woman to another.

Women education about childbirth is very important to empower women and enhance their health. One Jordanian study support the importance of education about the physiology of birth on birth outcomes. Hatamleh et al (2019) found that women who received childbirth education were having higher rates of spontaneous labour, larger diameter of cervix on admission and earlier initiation of breast feeding than control.

Finally, from the above, it is apparent that healthcare professional need adequate time during antenatal care to clarify to the pregnant woman and her husband the new recommended care process and the estimated time required for labouring and giving birth. This would go some way to alleviating the sociocultural pressures as, ultimately, it is not acceptable for such pressures to prevent the implementation of new evidence-based protocols in the maternity care units at governmental hospitals in Jordan and thus adversely affect the quality of care received by pregnant women and newborns.

Limitations

The main limitation in this study was the atmosphere in the maternal ward that did not support the idea of the study in a governmental hospital, which make it difficult to interview most of the physicians in the ward. Although they were the decision makers for caring process.

Conclusion

This study is considered to be the first to focus on the lack of use of evidence-based practices in maternal care in Jordanian governmental hospitals. The study found that healthcare professionals hold the opinion that limited resources, lack of midwife autonomy, the hospital environment, and sociocultural factors are all hindering the application of evidence-based practice in maternity care. However, the application of evidence-based care practices in maternity wards in Jordanian governmental hospitals would lead to a decrease in the morbidities and mortalities associated with pregnancy, labour, birth and the postpartum period.

Implications for nursing and health policy

Policy makers should make resources available to facilitate the application of evidence-based practices in maternal care. The health policy on maternal care should be modified to permit midwives to participate in decision making during labour and birth processes. Also, midwives need autonomy to provide the evidence-based practices. Furthermore, it is necessary to raise awareness among the public to persuade them to accept evidence-based practice as the best modality of labour and birth management.

Key points

- Jordanian healthy women become exposed to the side effects of unnecessary medical interventions

- Weak application of evidence-based practices in maternal care settings in Jordan

- Lack of resources and sociocultural practices are factors that prevent applying evidence based maternal care

CPD reflective questions

- What was the purpose of this research study?

- What were the main themes extracted from this study?

- What was the main message from this study that you can take home and inform others about?