The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF (2003) recommend exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months, ideally continuing for at least 2 years alongside foods. It is widely documented that breastfeeding has many benefits to both child and mother (Ip et al, 2007; Horta et al, 2015; Victora et al, 2016; WHO, 2018). Successful breastfeeding can also enhance infant–mother attachment relationships (Krol and Grossmann, 2018).

Despite these benefits, the rate of breastfeeding in the UK is still relatively low compared with other countries around the world, with the only exception being the USA (Renfrew et al, 2012; Nicholson and Hayward, 2021). While 74% of mothers in the UK initiate breastfeeding, the rate of continued breastfeeding drops to 44% at 6 weeks and then to 36% at 6 months (Renfrew et al, 2012; Nicholson and Hayward, 2021). Only 1% of babies are exclusively breastfed at 6 months despite WHO guidelines (Renfrew et al, 2012), lower than many other developed countries (Al-Sahab et al, 2010; Odar Stough et al, 2019).

Evidence suggests that women in the UK who are more highly educated and of higher socioeconomic status are most likely to initiate breastfeeding (Skafida, 2009). Personality traits such as extraversion and openness to experience, emotional stability and conscientiousness have been associated with initiation and continuation of breastfeeding (Wagner et al, 2006; Brown, 2014). There are many reasons why women decide to stop breastfeeding before the recommended 2 years, including returning to work, social and cultural pressures, a lack of social support from immediate family, physical and mental health issues and a lack of perceived information and support from healthcare professionals (Bai et al, 2009; Ogbuanu et al, 2009; Hauck et al, 2011; Oakley et al, 2014; Feenstra et al, 2018; Keevash et al, 2018; Scarborough et al, 2022).

Mental health difficulties following birth are not uncommon, with approximately 15–20% of women experiencing depression and/or anxiety in the first year following childbirth (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2014). While the causes of postpartum mental health difficulties are multifaceted, a perceived lack of information and support from both healthcare professionals and immediate family can increase the likelihood of developing such problems (Keevash et al, 2018). Women experiencing anxiety or depression are significantly less likely to initiate breastfeeding or maintain it longer term (Smith et al, 2015).

Other factors known to be linked to mental health more generally include coping strategies and personality variables (Carver and Connor-Smith, 2010). How people engage and cope with stressful events is an important factor for mental health and adjustment. Coping strategies are particularly key to ongoing wellbeing, with individuals who engage in more positive forms of coping (problem-focused coping) tending to experience improved wellbeing over those who engage in more negative coping strategies (avoidance coping) (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). More specifically, emotion-focused coping strategies, such as rumination, thinking avoidance, self-isolation, negative emotion expression, denial and self-blame, have been associated with increases in mental health difficulties (Luo et al, 2015; Colville et al, 2017; Naushad et al, 2019; Rodriguez-Rey et al, 2019).

Thurgood et al (2022) identified a link between high levels of perceived stress and low self-efficacy in reducing mothers' likelihood to continue breastfeeding. Qualitative research exploring coping strategies used by breastfeeding mothers found that increasing breastfeeding knowledge, relaxation, positive self-talk, challenging unhelpful beliefs, problem solving, goal setting and the practice of mindfulness were commonly reported (O'Brien et al, 2009). All of these factors can be considered forms of adaptive coping in terms of proactive attempts to deal with stress and taking practical action to address problems. Similar strategies have been found to be effective in stress management programmes for breastfeeding mothers (Azizi et al, 2020).

Appraisal of life events is also important, with individuals who have a positive outlook on life tending to fair better in stressful situations than those with a more pessimistic outlook (Cruz et al, 2018). Trait optimism, the tendency to hold favourable expectancies for the future, is generally associated with adaptive coping and with lower levels of disengagement and avoidance (Carver and Connor-Smith, 2010). Optimism is also associated with better subjective wellbeing, healthy behaviours and appears protective against low mood in a range of health contexts. O'Brien et al (2008) showed that women with higher optimism were likely to breastfeed for longer. However, more recently, a study in Spain found that women who breastfed for longer reported lower levels of optimism and higher levels of stress by 3 months postpartum (Gila-Díaz et al, 2020).

To better understand the relationship between breastfeeding duration and mental health, it is important to understand how these other variables may influence this relationship. The importance of mental health, stress and optimism have already been implicated in breastfeeding duration (O' Brien et al, 2008; Gila-Diaz et al, 2020), although the evidence for a link between optimism and breastfeeding duration remains limited (Gila-Diaz et al, 2020). Moreover, these studies do not examine the influence of coping strategies.

The present study's aim was to unpick the relationship between breastfeeding duration and mental health further by identifying the relationships between coping strategies and optimism on breastfeeding duration and mental health, and on the relationship between these two factors. It was predicted that women who breastfed for longer would report lower levels of anxiety and depression and higher levels of optimism. It was expected that these women would also report using more adaptive coping strategies and fewer less adaptive strategies. Finally, it was predicted that the associations between breastfeeding duration and depression and anxiety would be mediated by optimism, such that the effects of negative mood would be reduced.

Methods

Participants were recruited using an existing database of 1505 individuals who had previously taken part in studies on breastfeeding carried out by the second author and colleagues (Keevash et al, 2018; Norman, et al, 2022; Scarborough et al, 2022) and who had expressed an interest in taking part in future studies. Participants were eligible to take part in the study if they had breastfed an infant for any period in the 5 years prior to data collection for the present study. There was no specified minimum duration of breastfeeding to allow women who had tried it (even just for a few hours) to take part in the study.

Data collection

Data were collected between January and May 2017. A total of 708 participants completed an online survey hosted on SurveyMonkey (a response rate of 47%). Of these, 90 did not complete the full study and a further 6 had not attempted to breastfeed at all. These were removed from the dataset, leaving a total of 612 participants (all of whom identified as women) in the analysis.

The advert, information sheet and a link to the study questionnaire were emailed to all women on the breastfeeding database. Those interested in participating were invited to click on the link to the survey and complete it online. The survey consisted of a range of self-designed questionnaires measuring demographic information, age, ethnicity and employment status, breastfeeding duration, and reasons for stopping breastfeeding, where applicable. For breastfeeding duration, it was noted whether women had ceased breastfeeding at the time of the study, but had breastfed for 12 months or more, or whether they were still breastfeeding at the time of the study and had been doing so for over 12 months. After providing this information, the participants completed several validated measures.

The hospital anxiety and depression scale (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983) is a widely used measure of anxiety and depression. The two conditions frequently coexist, and anxiety often precedes depression in response to stressors. The scale comprises seven questions each for anxiety and depression, each describing a way that participants may have felt or acted over the previous week. Responses were graded on a 4-point scale (0–3) and summed to obtain separate anxiety and depression scores, with a maximum of 21 for each.

The cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (Garnefski et al, 2001) outlines nine distinct cognitive coping strategies that support the regulation of emotion. Research has supported these classifications, and the potential for positive or negative emotional outcomes respectively, across a range of applied health settings, including identification of targets for intervention (Garnefski and Kraaij, 2012; Garnefski et al, 2013; Kraaij and Garnefski, 2015). Five strategies are classed as adaptive:

- Putting into perspective: emphasising severity in relation to worse possibilities

- Positive refocusing: thinking about more joyful and pleasant issues

- Positive reappraisal: finding a positive meaning in terms of personal growth

- Acceptance: accepting and resigning to what has happened

- Planning: thinking about how to handle the situation proactively.

The remaining four strategies on the questionnaire are classed as maladaptive:

- Self-and-other blame: putting blame for the event on the self or another person respectively

- Rumination: repeatedly dwelling on feelings and thoughts associated with the negative event

- Catastrophising: emphasising the terror and extremity of the experience.

The questionnaire measures the nine strategies via a subscale of four items reflecting what individuals may think after experiencing a stressful or threatening event. Participants respond to each item on a scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). A subscale score was obtained by summing responses to the four items, giving a maximum score of 20. The measure was included in the present study to identify whether cognitive and emotional regulation played a role in maintaining breastfeeding.

The brief coping orientation to problems experienced inventory (Carver, 1997) was also used. Kraaij et al (2008) identified three problem-focused coping strategies that are not captured in the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire and measured these using relevant items from the coping orientation to problems experienced inventory: emotional support (obtaining emotional support/comfort and understanding), active coping (actively doing something to improve the situation), and substance abuse (using alcohol/drugs). These were measured in the present study, but also included two further scales, instrumental support (getting help and advice) and religion (using religious/spiritual beliefs and practices to find comfort). Each strategy was measured using two items.

The life orientation test (Scheier et al, 1994) is a 10-item scale that measures dispositional optimism, the general tendency to believe that one will experience good, rather than bad, life outcomes. Four items were fillers, and responses on the remaining six items were averaged to obtain an overall score. This scale was included to identify whether optimism or pessimism played a role in breastfeeding duration.

Data analysis

For the hospital anxiety and depression scale, a higher score indicated higher levels of anxiety or depression. Scores were categorised as follows: ≤7 indicated no anxiety/depression, 8–10 a mild case, 11–14 a moderate case and 15–21 a severe case. For the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire, the higher the score, the more the specific cognitive coping strategy was used. Brief coping orientation to problems experienced inventory scores were computed as the sum of responses across the two items for each coping style measured. For the life orientation test, a higher value indicated a higher level of optimism.

Analysis of variance was used to test for partial correlations between anxiety, depression and other variables by breastfeeding duration. Multivariate analysis of variance was used to compare duration groups across the nine cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire coping strategies and five coping orientation to problems experienced inventory strategies.

Feeding duration was coded whereby <3 months was coded 1, 3–6 months was 2, 7–12 months was 3, >12 months was 4 and still breastfeeding was 5. These were used as the dependent variable in ordinal logistic regression. Participant age, education (coded 1–5, where 1=no formal qualifications and 5=PhD/doctoral level), number of children, ethnicity (coded White=1, other=0), marital/cohabiting status (1=yes; 0=no), together with all other variables.

To test whether optimism (life orientation test score) mediated the effects of anxiety and depression on duration of breastfeeding, a mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro for the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, model 4 (Hayes, 2018). In all analysis, the critical value of P was 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained for the study through the University of Plymouth faculty ethics committee (reference: 14/15-371). Participation was entirely voluntary, and participants gave written informed consent before completing the survey. Data were anonymised and no identifying information was collected.

Results

The participants' mean age was 35.64 years (±5.15 years). Of these, 78.3% (n=479) were White, 18.6% (n=114) were Black, Asian or mixed race, and the remaining 3.1% (n=19) were ‘other’ or did not specify. The majority (n=588; 96.1%) were married or cohabitating, 78.1% (n=478) were educated to at least undergraduate degree level, 85.9% (n=526) had one or two other children at home and 3.4% (n=21) reported having four or more other children. No participants were first-time mothers.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the whole sample and by breastfeeding duration. Overall, mean anxiety and depression scores were low, with 54.1% (n=333) of participants scoring ≤7 on anxiety and 77.3% (n=473) on depression, indicating no anxiety/depression. Only 6.4% (n=39) scored ≥15 on anxiety and only 1.1% (n=7) on depression.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for overall sample and by breastfeeding duration

| Full sample | Mean ± standard deviation by breastfeeding duration (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3, n=69 | 3–6, n=36 | 7–12, n=106 | >12, n=236 | Still breastfeeding >12 months, n=105 | ||

| Anxiety | 7.60 ± 4.29 | 8.65 ± 5.05 | 8.22 ± 4.45 | 7.08 ± 4.15 | 7.51 ± 4.16 | 7.44 ± 4.08 |

| Depression | 4.86 ± 3.62 | 4.55 ± 3.13 | 4.39 ± 2.95 | 4.69 ± 3.59 | 5.03 ± 3.79 | 5.02 ± 3.81 |

| Positive refocus* | 9.93 ± 3.23 | 10.68 ± 3.73 | 10.17 ± 2.67 | 9.47 ± 2.70 | 9.89 ± 3.30 | 9.90 ± 3.33 |

| Planning * | 12.53 ± 3.34 | 12.55 ± 3.39 | 12.25 ± 3.19 | 12.41 ± 3.47 | 12.66 ± 3.32 | 12.43 ± 3.32 |

| Positive reappraisal* | 12.13 ± 3.71 | 12.43 ± 3.65 | 12.06 ± 3.63 | 12.05 ± 3.49 | 12.22 ± 3.84 | 11.81 ± 3.73 |

| Put in perspective* | 13.03 ± 3.55 | 13.49 ± 3.86 | 13.06 ± 3.53 | 13.13 ± 3.45 | 12.87 ± 3.57 | 12.95 ± 3.46 |

| Acceptance* | 10.66 ± 3.18 | 12.49 ± 3.58 | 10.61 ± 2.84 | 10.6 ± 3.15 | 10.23 ± 3.00 | 10.51 ± 3.09 |

| Self-blame* | 9.32 ± 3.41 | 9.84 ± 3.90 | 9.72 ± 3.61 | 9.40 ± 3.39 | 9.19 ± 3.37 | 9.05 ± 3.12 |

| Rumination* | 11.09 ± 3.76 | 10.97 ± 3.64 | 11.08 ± 3.99 | 10.91 ± 3.68 | 11.39 ± 3.95 | 10.67 ± 3.39 |

| Catastrophising* | 7.01 ± 2.86 | 7.28 ± 3.07 | 6.83 ± 2.75 | 6.92 ± 3.36 | 7.04 ± 2.72 | 6.92 ± 2.56 |

| Other-blame* | 8.36 ± 2.79 | 7.80 ± 3.06 | 8.31 ± 1.97 | 8.06 ± 2.67 | 8.44 ± 2.74 | 8.86 ± 3.02 |

| Active coping† | 5.64 ± 1.78 | 5.70 ± 1.87 | 5.36 ± 1.62 | 5.68 ± 1.76 | 5.77 ± 1.75 | 5.40 ± 1.87 |

| Substance use† | 3.05 ± 1.23 | 3.01 ± 1.27 | 3.11 ± 1.37 | 3.21 ± 1.19 | 3.02 ± 1.29 | 2.96 ± 1.07 |

| Emotional support† | 5.51 ± 1.72 | 5.52 ± 1.69 | 5.39 ± 1.57 | 5.46 ± 1.81 | 5.56 ± 1.73 | 5.46 ± 1.67 |

| Instrumental support† | 5.58 ± 1.92 | 5.83 ± 1.90 | 5.69 ± 1.62 | 5.67 ± 1.92 | 5.52 ± 1.96 | 5.42 ± 1.93 |

| Religion† | 2.75 ± 1.48 | 2.61 ± 1.46 | 2.47 ± 0.88 | 2.73 ± 1.47 | 2.92 ± 1.59 | 2.57 ± 1.41 |

| Life orientation‡ | 19.76 ± 7.10 | 16.62 ± 8.30 | 19.08 ± 6.29 | 20.42 ± 6.78 | 20.12 ± 7.13 | 20.56 ± 6.29 |

coping strategies measured by brief coping orientation to problems experienced inventory,

‡Optimism

Overall, 165 women were still breastfeeding at the time data were collected, of which 105 had done so for over 12 months. The remaining 60 were breastfeeding younger babies and were removed from the sample before further analysis, as their breastfeeding duration was undetermined. Analysis of variance indicated no significant differences between duration groups in anxiety (F(4, 547)=1.68, P=0.15), or depression (F(4, 547)=0.52, P=0.73. However, a significant difference in life orientation test scores (optimism) was observed (F(4, 547)=4.26, P=0.002). Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction indicated that women who breastfed for <3 months had lower optimism scores than those in all other duration categories; 3–6 months (P=0.89); 7–12 months (P=0.005); >12 months (P=0.003), and still breastfeeding >12 months (P=0.003).

Multivariate analysis of variance revealed only one significant effect, for acceptance (F(4, 547)=7.16, P<0.001, η2=0.05). Women who breastfed for <3 months reported significantly more acceptance than all other groups; for 3–6 months (P=0.03), all other cases (P<0.001).

Tables 2 and 3 present bivariate correlations between anxiety, depression and other variables. Anxiety and depression were themselves significantly correlated (r=0.60, P<0.001), and were also negatively associated with optimism (anxiety: r=0.41, P<0.001; depression: r=0.32, P<0.001). Anxiety and depression were generally positively correlated with self-blame, rumination, catastrophising and substance use, suggesting that individuals who scored higher on anxiety and depression made greater use of these theoretically less adaptive strategies. Anxiety and depression were negatively correlated with positive refocus, refocus on planning, putting into perspective and positive reappraisal.

Table 2. Partial correlations between anxiety and other variables by breastfeeding duration

| Anxiety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3, n=69 | 3–6, n=36 | 7–12, n=106 | >12, n=236 | Still breastfeeding >12 months, n=105 | |

| Positive refocus | -0.28* | -0.42* | -0.28* | -0.17* | -0.18 |

| Planning | -0.39† | -0.01 | -0.17 | -0.12 | -0.20* |

| Positive reappraisal | -0.33† | -0.19 | -0.18 | -0.18* | -0.28* |

| Put into perspective | -0.21 | -0.10 | -0.13 | -0.19* | -0.18 |

| Acceptance | 0.27* | 0.49* | 0.20* | -0.10 | -0.04 |

| Self-blame | 0.50† | 0.50* | 0.40* | 0.41† | 0.25* |

| Rumination | 0.39† | 0.60† | 0.22* | 0.42† | 0.20* |

| Catastrophising | 0.33† | 0.59† | 0.28* | 0.43† | 0.32† |

| Other-blame | -0.06 | 0.04 | -0.06 | 0.10 | 0.25* |

| Active coping | 0.05 | -0.20 | -0.13 | -0.10 | -0.08 |

| Substance use | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.24* | 0.23* | 0.25* |

| Emotional support | 0.03 | 0.21 | -0.10 | -0.04 | -0.10 |

| Instrumental support | -0.09 | 0.07 | -0.14 | -0.07 | -0.17 |

| Religion | 0.21 | -0.23 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.17 |

| Life orientation | -0.37† | -0.50* | -0.54† | -0.41† | -0.39† |

Note: results are controlled for mother's age, education, number of children, marital/cohabitating status and ethnicity.

*P<0.05,

†P<0.01

Table 3. Partial correlations between depression and other variables by breastfeeding duration

| Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3, n=69 | 3–6, n=36 | 7–12, n=106 | >12, n=236 | Still breastfeeding >12 months, n=105 | |

| Positive refocus | -0.46† | -0.51* | -0.34† | -0.24† | -0.30* |

| Planning | -0.40† | -0.16 | -0.28* | -0.23† | -0.20* |

| Positive reappraisal | -0.40† | -0.39* | -0.33† | -0.27† | -0.30* |

| Put into perspective | -0.37* | -0.25 | -0.14 | -0.23† | -0.21- |

| Acceptance | -0.05 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Self-blame | 0.40† | 0.47* | 0.31* | 0.27† | 0.27* |

| Rumination | 0.41† | 0.51† | 0.12 | 0.25† | 0.21* |

| Catastrophising | 0.31* | 0.63† | 0.18 | 0.35† | 0.31* |

| Other-blame | -0.05 | -0.05 | -0.06 | 0.06 | 0.22* |

| Active coping | -0.17 | -0.25 | -0.26* | -0.21† | -0.09 |

| Substance use | 0.21 | 0.38* | 0.25* | 0.18* | 0.34* |

| Emotional support | -0.09 | 0.04 | -0.29* | -0.16* | -0.14 |

| Instrumental support | -0.06 | 0.07 | -0.24* | -0.22† | -0.22* |

| Religion | 0.14 | 0.04 | -0.04 | 0.07 | -0.07 |

| Life orientation | -0.34* | -0.44* | -0.44† | -0.35† | -0.40† |

Note: results are controlled for mother's age, education, number of children, marital/cohabitating status and ethnicity.

*P<0.05,

†P<0.01

On the whole, the trend was for anxiety and depression to be negatively associated with coping strategies that are considered adaptive, and positively with those considered less adaptive. The exception was acceptance, which showed positive associations with anxiety only in breastfeeding <12 months, and no significant associations with depression. Optimism was negatively associated with both anxiety and depression in all duration groups. Some differences in correlations were observed between mood and coping at differing breastfeeding durations. Other-blame was found be positively correlated with both anxiety and depression in women who were still breastfeeding after 12 months, but showed no significant association in other duration groups. Seeking instrumental and/or emotional support were significantly negatively associated with depression at durations of >6 months only.

Table 4 presents the results of ordinal logistic regression. The model accounted for 20% variance in breastfeeding duration (Nagelkerke pseudo R2=0.20). Women who breastfed for longest, or who were still breastfeeding after ≥12 months, tended to have fewer children, be more highly educated and married/cohabiting. Variance in breastfeeding duration was significantly accounted for by higher levels of depression, other-blame and optimism, and lower levels of acceptance and instrumental support.

Table 4. Ordinal logistic regression for duration of breastfeeding

| Variable | Beta | 95% confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.02 | 0.23–0.23 | 0.15 |

| Education | 0.18 | 0.01–0.01 | 0.005 |

| Number of children | -0.70 | 0.27–0.27 | <0.001 |

| Married/cohabiting | 0.96 | -1.78–-0.13 | 0.02 |

| Ethnicity | 0.16 | -0.23–0.55 | 0.41 |

| Anxiety | -0.03 | -0.08–0.02 | 0.23 |

| Depression | 0.08 | 0.02–0.14 | 0.01 |

| Positive refocus | -0.04 | -0.10–0.03 | 0.27 |

| Refocus on planning | 0.02 | -0.05–0.09 | 0.56 |

| Positive reappraisal | 0.00 | -0.06–0.07 | 0.95 |

| Out into perspective | -0.03 | -0.09–0.03 | 0.31 |

| Acceptance | -0.07 | -0.13–-0.02 | 0.01 |

| Self-blame | 0.01 | -0.06–0.08 | 0.84 |

| Rumination | 0.00 | -0.06–0.07 | 0.95 |

| Catastrophising | -0.02 | -0.10–0.06 | 0.63 |

| Other-blame | 0.07 | 0.01–0.14 | 0.02 |

| Active coping | 0.04 | -0.08–0.15 | 0.53 |

| Substance use | 0.00 | -0.14–0.13 | 0.96 |

| Emotional support | 0.11 | -0.03–0.24 | 0.12 |

| Instrumental support | -0.18 | -0.30–-0.06 | <0.003 |

| Religion | 0.03 | -0.07–0.14 | 0.53 |

| Life orientation | 0.04 | 0.01–0.07 | <0.003 |

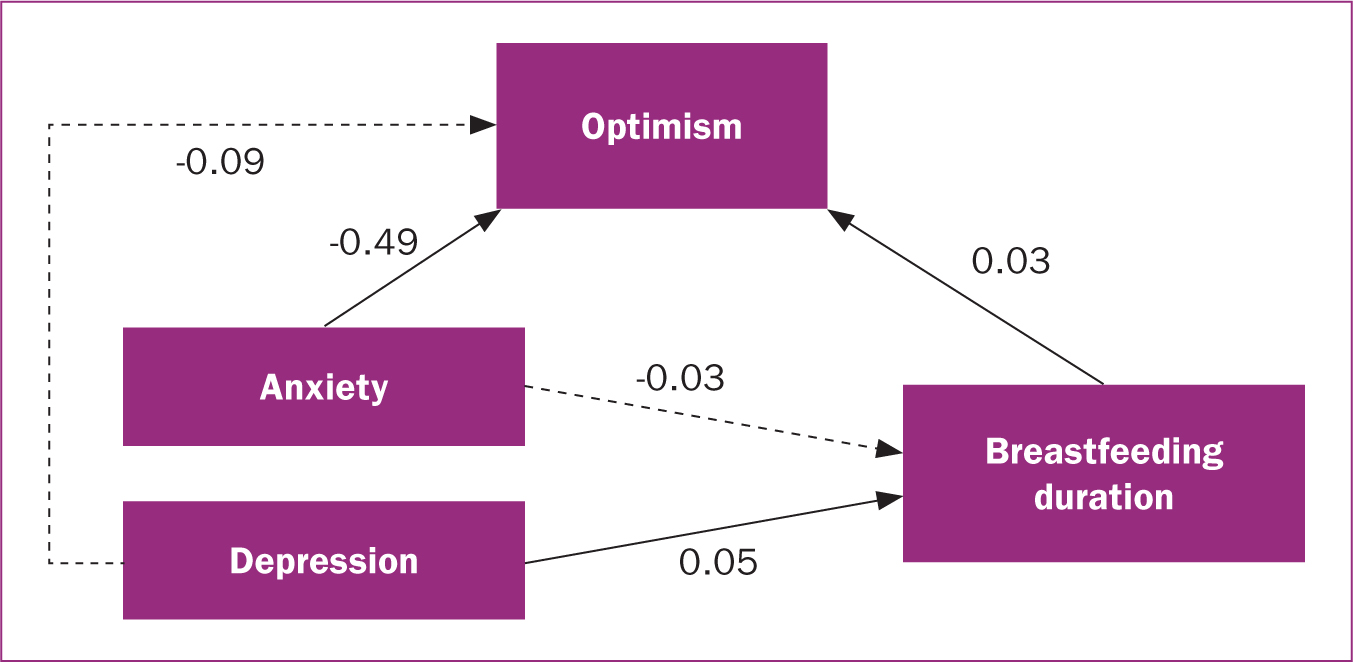

As shown in Figure 1, anxiety showed no significant direct association with breastfeeding duration, but a significant indirect effect via optimism was observed (β=-0.01, 95% confidence interval: -0.02, -0.004). For depression, there was a significant positive direct association with duration, but no significant indirect effect (β=-0.002, 95% confidence interval: -0.01, 0.003).

Table 5 shows reasons for cessation of breastfeeding by duration. In the high duration group, the most frequently cited reason was natural weaning, followed by personal choice (women who felt it was time for them to stop breastfeeding). For those women who ceased breastfeeding within 6 months, feeding complications were a major issue reported. In all groups, a proportion of women ceased breastfeeding as they were required to spend time apart from their child for a variety of reasons. Analysis of the reasons for stopping identified no significant differences in coping measures or mental health across the different groups. Analysis within the reasons for stopping groups also failed to identify any meaningful differences.

Table 5. Duration of breastfeeding and reason for cessation

| Frequency by breastfeeding duration in months, n=612 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | <3, n=78 | 3–6, n=42 | 7–12, n=124 | >12, n=272 |

| Maternal condition | 12 (15.4) | 2 (4.8) | 7 (5.6) | 5 (1.8) |

| Paediatric condition | 8 (10.3) | 2 (4.8) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (1.1) |

| Natural weaning | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 26 (21.0) | 172 (63.2) |

| Mental health | 6 (7.7) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (3.2) | 12 (4.4) |

| External pressure | 2 (2.6) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (3.2) | 6 (2.2) |

| Personal choice | 2 (2.6) | 6 (14.3) | 15 (12.1) | 35 (12.9) |

| Feeding complications | 31 (39.7) | 13 (31.0) | 23 (18.5) | 11 (4.0) |

| Time apart | 3 (3.8) | 11 (26.2) | 36 (29.0) | 27 (9.9) |

| Unsupported | 14 (17.9) | 3 (7.1) | 7 (5.6) | 1 (.4) |

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between breastfeeding duration and mental health, and examined their association with coping and optimism. A direct relationship was found between breastfeeding duration and depression, but not anxiety. Rates of depression were higher in those who had breastfed for more than 12 months and those who were still breastfeeding, than in those who had ceased breastfeeding earlier. Optimism was negatively associated with both anxiety and depression, irrespective of breastfeeding duration. There was no significant mediating effect of optimism on the association between depression and breastfeeding duration, but optimism did mediate the relationship between anxiety and duration.

Across all breastfeeding duration categories, positive correlations were identified between both anxiety and depression, and coping strategies generally defined as least adaptive: self-blame, rumination, catastrophising and substance use. This is in-keeping with current psychological literature that has already identified a significant link between anxiety and depression and these coping strategies and cognitive-emotional approaches (Luo et al, 2015; Colville et al, 2017; Naushad et al, 2019; Rodriguez-Rey et al, 2019). Coping with emotions by blaming others was also positively correlated with both anxiety and depression but only in women still breastfeeding after 12 months.

Adaptive coping strategies, positive refocus, refocus on planning, positive reappraisal and putting the situation into perspective were negatively correlated with anxiety and depression in most breastfeeding duration groups. Correlation coefficients were mostly very similar and variations in significance levels can largely be accounted for by differences in sample size in the groups. The exceptions were in groups representing breastfeeding between 3 and 12 months, where the data suggest little association between these strategies and anxiety. Seeking instrumental support did not correlate with anxiety scores but was negatively associated with depression in women breastfeeding for over 6 months. While it is not possible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship, it does raise the possibility that those who sought instrumental support with breastfeeding were experiencing more anxiety and coping least well, earlier in their breastfeeding experience, although the data do not provide evidence to suggest that this anxiety directly led to early cessation.

The coping strategy acceptance was positively correlated with anxiety across all durations and with depression in those breastfeeding for 3–6 months and 7–12 months, and those who were still breastfeeding. This highlights that high acceptance was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Although acceptance was initially conceptualised as an adaptive strategy (Garnefski et al, 2001), research has increasingly suggested that it can be negatively associated with wellbeing and positively associated with psychological distress (Martin and Dahlen, 2015; Feliu-Soler et al, 2017; Bacon and Charlesford, 2018; Bacon et al, 2023). It is suggested that items that make up the acceptance subscale (such as ‘I think that I cannot change anything about it’ or ‘I think that I must learn to live with it’) may reflect feelings of hopelessness rather than adjustment. Further qualitative investigations have highlighted the existence of distinct forms of acceptance (resignation, automatic counteracting and behavioural adapting) (Liersch, 2020). While behavioural adapting is associated with positive coping, both resignation and automatic counteracting (a reactive urge to find relief or solution) are more synonymous with maladaptive coping. Moreover, in the present study, women who ceased breastfeeding before 3 months reported significantly higher levels of acceptance than those who had breastfed for more than 12 months or who were still breastfeeding. This finding may also reflect a sense of hopelessness with the situation, leading to cessation. The findings from the present study lend support to the proposal that acceptance in coping needs further investigation.

The complex relationships between mental health and coping may shed light on the unexpected finding that women who had breastfed for longer, or who were still breastfeeding, reported higher levels of depression than those who had stopped feeding earlier. This is in contrast to previous studies, which have identified that greater mental health difficulties are associated with shorter duration of breastfeeding (Smith et al, 2015). The logistic regression highlighted that although those who breastfed for longer scored higher on levels of optimism, they also reported higher levels of other-blame and lower use of instrumental support as a coping strategy. This final factor is likely to relate to how long the participants had been breastfeeding for. While instrumental support for breastfeeding is not likely to be a necessity once breastfeeding has been successfully established, there is a potential need for longer-term emotional support from family members, friends and healthcare professionals to ensure women feel able to continue breastfeed without experiencing negative mental health effects (Theodorah and Mc'Deline, 2021; Scarborough et al, 2022).

Breastfeeding is not an easy process and is associated with many physical and psychological changes that may account for feelings of depression, such as a sense of not being in control of one's body (Borders et al, 2013), appearance concerns (Swanson et al, 2017) and feeling exhausted or fatigued (Phillips et al, 2020). While the focus on depression and anxiety in early breastfeeding is important, it is equally necessary that research focuses on longer-term links to fully understand the nature of the relationship between mental health and breastfeeding. The higher rate of depression observed in those who had been breastfeeding longer-term, and in those who were still breastfeeding, warrants further investigation.

Implications for practice

The present study demonstrated a link between anxiety in breastfeeding women and a need for optimism to enhance the likelihood of longer-term breastfeeding. While breastfeeding is good for both women and infants, there has to be recognition by all healthcare professionals that the process is not as natural and straightforward as people may believe it to be when first embarking on their breastfeeding journey. Awareness training among healthcare professionals, not just those working in areas of health visiting and midwifery, about the difficulties associated with breastfeeding and the importance of providing signposting, emotional support and empathy may help to provide those who breastfeed with a sense of optimism that they can overcome their anxieties and continue to breastfeed over time. This would also help to reduce the level of depression experienced by people who breastfeed longer term. Finally, targeting specific support at individuals who may be more at risk of ceasing breastfeeding, such as those who have experienced early separation from their infant may help to improve long-term breastfeeding rates and reduce associated anxiety and depression in parents.

Limitations

While the present study included many women across the whole of the UK who had breastfed for a varying period, the overall sample cannot be generalised to the UK population. The percentage of women breastfeeding for over 6 months in the study (n=507, 82%) is far higher than the national average (36%) (Renfrew et al, 2012; Nicholson and Hayward, 2021). Furthermore, analysis of the education data, used as a proxy for socioeconomic status, and the ethnicity data, highlights that the participants were from predominantly white middle class backgrounds. While social media was used to reach a wider target audience, as with many previous online studies, the approach was unable to attract a representative sample (Scarborough et al, 2022). Further study needs to be conducted with women from ethnic minorities living in the UK and in deprived communities to identify whether these findings hold across the population of breastfeeding mothers.

Finally, the study used a cross-sectional retrospective design asking women about current or recently ceased breastfeeding behaviour, mental health and coping strategies. A more effective way to identify the complex inter-relationships between these variables would be to conduct a longitudinal study starting in pregnancy to breastfeeding cessation across a wide sample of the UK population.

Conclusions

This study identifies the need for continued research into the complex relationship between mental health and breastfeeding behaviour, and the impact that variables such as optimism and coping strategies may have. Further study is also needed into the links between these variables and reasons for ceasing breastfeeding, particularly prior to 6 months postpartum.

The study has highlighted that breastfeeding can be a difficult experience that can be associated with mental health difficulties. There is a need for improved support for women during their breastfeeding experience. Specifically, increased support is needed for women with anxiety symptoms, to help them to build their sense of optimism and enhance their chances of breastfeeding for longer. Healthcare professionals need to consider how services can provide longer-term emotional support for women who breastfeed, to mitigate the potential for developing depressive symptoms. Emotional, and instrumental breastfeeding support is also needed from women who have experienced time apart early in their breastfeeding journey and may, therefore, be at risk of early cessation and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Although the exact mechanism by which these variables interact remains unclear, this study highlights the need for further investigation into the complex multifaceted relationship between mental health and breastfeeding duration. It further highlights women's need of long-term emotional support from family and friends, but also from healthcare professionals.

Key points

- This study examined the association between maternal mental health and breastfeeding duration, and the role of optimism and coping strategies in this association.

- In general terms, women with higher levels of anxiety and depression breastfed for less time, while those who were optimistic breastfed for longer.

- Optimism mediated the association between anxiety and breastfeeding duration, suggesting that women higher in optimism breastfed for longer despite their anxiety.

- Higher depression was associated with shorter breastfeeding duration, but optimism had no effect on this relationship.

- Women who ceased breastfeeding before 3 months reported significantly higher levels of acceptance coping than those with longer breastfeeding durations.

- Optimism is important in maintaining breastfeeding.

CPD reflective questions

- How might anxious women be encouraged to be more optimistic about breastfeeding?

- How might midwives detect that a woman is anxious or depressed, especially if this is not directly related to childbirth or pregnancy concerns?

- What is the role of a partner in supporting continued breastfeeding and how might midwives support this?

- Should women considering stopping breastfeeding after a short time because of feeding difficulties be encouraged to continue, rather than accept that situation?