According to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 statistics, every day about 1000 women die during childbirth. Of these deaths, 99% occur in developing countries (WHO, 2014). The global neonatal (0–28 days of life) mortality rate (NMR) is 23/1000 lives births; however, many of these deaths can be prevented by providing accessible antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal care through skilled birth attendance (UNICEF, 2011). In Pakistan in 2008, the maternal mortality rate is between 260–700/100 000 and the NMR is reported to be 42/1000 live births—highest among all the South Asian countries (National Institute of Population Studies Islamabad, 2008; UNICEF, 2011). Furthermore, the availability of skilled birth attendants for women during childbirth is only 38.8% (Jafarey et al, 2008).

Globally, midwives are the primary carers for women before, during, and after childbirth. According to the literature, different models of care are practised to provide support and assistance to women during the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal period (Sandall et al, 2013). The most commonly used models are obstetric, shared, and midwife-led care. In obstetric-led care, the obstetrician dictates and provides care during the antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal period with support from midwives. In shared care, the responsibility is distributed among different health professionals such as obstetricians, midwives, and general practitioners during various phases of the maternity care (Sandall et al, 2013). Midwife-led care is where the midwife, primarily, carries out the planning, organising, and delivery of care though out a low-risk pregnancy and into to the postnatal period (Sandall et al, 2013). Evidence-based literature from both developed and developing countries highlights midwifery-led care as instrumental in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality (Rukanuddin et al, 2007; Gu et al, 2011; Sandall et al, 2013). In this model, continuity of care is the key to providing safe and effective care to women. Midwives work in collaboration with obstetricians to promote normality in childbirth. This independent and confident midwifery practice makes childbirth safe for women and produces effective outcomes, such as positive birth experiences and good physical and psychological wellbeing for women (Gibbins and Thomson, 2001; Homer et al, 2009; Gu et al, 2011; Anwar et al 2014).

Studies assert that midwives' continuous presence provides encouragement to women during the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods (Homer et al, 2009; Gu et al, 2011). Continuity of care increases the women's satisfaction and trust in midwives (Anwar et al, 2014). In the phenomenological study conducted by Gu et al (2011) in China, midwives reported that while providing maternity care to women, the women become familiar with them, which they felt helped women remain stress-free and able to make appropriate decisions during their childbirth continuum. The continuity of care in the midwifery-led care model enhanced the midwives' job satisfaction due to autonomy of practice such as vaginal examinations and births. Midwives working in obstetric-led models reported dissatisfaction due to reduced continuity of care and use of acquired skills. Moreover, some studies in developed countries identified that midwives practising in a midwifery-led care model promoted spontaneous vaginal births at a lower cost and reduced medical interventions at home or within secondary and tertiary hospitals (Sandall, 2012).

For the provision of services in the midwife-led care model, midwives must be knowledgeable and skilful to conduct normal deliveries (Sandall et al, 2013). They should be capable of caring for women throughout the childbirth continuum and provide information related to the birth process, breastfeeding, family planning, and diet during antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal periods (Gu et al, 2011). This will help women to make informed choices about birth.

Midwife-led care is popular in many developed countries, where autonomous trained midwives are responsible for providing maternity care to women during childbirth. This model is urgently required in countries like Pakistan, especially in low socioeconomical communities and rural areas where obstetric care is unaffordable and inaccessible to women and where medical services are provided on a fee-for-service basis. Women in these areas tend to opt for less expensive alternatives, such as traditional birth attendants who have do not have any formal training. Here, midwifery-led care would be a cost-effective alternative. Neighbouring countries such as India and Bangladesh have declining rates of maternal and neonatal mortalities due to the initiation of the midwifery-led care strategy (UNICEF, 2011). In many hospitals in Pakistan, midwives' practices include assisting physicians during childbirth and giving postnatal care to the mothers (Shahnaz, 2010; unpublished). In addition, it has been observed that in the antenatal clinics of hospitals, midwives often only observe women and monitor their vital signs because obstetric-led care is the preferred model (Rukanuddin et al, 2007).

In Pakistan, many private and tertiary care hospitals provide midwifery training. These include a pupil midwifery (15 months direct-entry programme), community midwifery (18 months training) and nurse-midwifery (12 months post-licensure). The curriculum of the Pakistan Nursing Council (PNC, 2003) prescribes that midwives should be competent and autonomous in their midwifery practices. The curriculum comprises: screening measures during childbearing, assessing mother or infant complications, and giving appropriate information, education, and counselling to women and families, in the hospital and community. However, in many maternity hospitals in Pakistan, midwives are not able to provide their full scope of services. Consequently, it is believed that the midwives are less competent and unable to conduct births independently.

As previously identified in the literature, midwifery-led care has demonstrated many advantages to the economy, women and midwives in developed and developing countries. However, a gap exists in Pakistan around the exploration of the use of midwifery-led care and understanding midwives' experiences. This study, therefore, aimed to address midwives' experiences of care provision.

The study was conducted in one of the tertiary care hospitals in Karachi, in which four maternity secondary sites were merged in 2009. To enhance autonomous midwifery care practices, midwifery-led care has been introduced to two sites alongside the existing obstetric-led care. Ten years ago, independent midwifery care was practised at these sites. However, over time this position has weakened and independent maternity care has been dominated by obstetric care. The purpose of the study was to explore the experiences and perceptions of Pakistani midwives practising the midwifery-led care model in two secondary maternity sites. The study also aimed to identify some of the facilitators and barriers to practising the model.

Methods

The study used qualitative descriptive design to explore the experiences and perceptions of midwives practising midwifery-led care (Polit and Beck, 2004).

A total of 10 midwives were recruited for the study. Purposive sampling was used to obtain rich information related to the phenomenon under study. Data were collected until no new, or repetitive, information emerged from the participants' interviews. Although data saturation was achieved with eight participants, two more interviews were conducted to ensure that no new information was emerging.

Ethical approval

Study approval was received from the hospital Ethical Review Committee and written permission was granted from the manager of the nursing and midwifery services at each site. The midwifery ward managers of these sites were informed about the proposed study. They were approached to identify midwives meeting the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria involved having an active license from the PNC, currently practising a midwifery-led care model, being able to give consent and express their feelings. The study participants were briefed about the purpose of the study by the researcher on a one-to-one basis. Midwives who were willing to participate, after understanding the study, were recruited. The availability of the participants dictated the date, time and venue for the interview.

At maternity site one, the midwives provided antenatal services under the supervision of an obstetrician but births were conducted by doctors under training. At maternity site two, women received antenatal care from the midwives under obstetric supervision and midwives conducted the births.

Data collection

The data were collected between April to June, 2012. Most of the interviews lasted for 30 to 45 minutes. An Urdu consent form was used to ensure understanding by the participants. Participants' confidentiality and anonymity were maintained by the use of code numbers and pseudonyms. A semi-structured interview guide, consisting of open-ended questions, was used by the researcher for the interview. Prior to the interview, demographic data were obtained. Throughout the interview, field notes were also taken to record the facial expressions and emotions of the participants during the interview.

In qualitative research, data analysis begins simultaneously with data collection (Polit and Beck, 2004). Therefore, data analysis of the study was initiated manually within the first interview by the researcher. The data interpretation process was done using Creswell's six steps of content analysis (Creswell, 2003). First, data were organised and prepared for analysis. All participants' data were given specific code numbers and pseudonyms to maintain anonymity. The verbatim (in Urdu language) was written manually after listening; and then all Urdu data were transcribed by the professional transcriber who had command of both the Urdu and English languages.

Word 2003 enabled each interview to be placed in columns; the left column was for Urdu and right was for English. One more column was added for coding. Four columns were then created in the second document in which codes from the first document were organised. Similarities and differences in the codes were gathered to form sub categories in the second column. Sub categories were then compared and contrasted to elicit new categories or to merge categories, and these were written in the third column of the document. Finally, a tree diagram was developed to provide more clarity about relationships between the categories and the themes. During this process, ongoing meetings were held with the thesis supervisor and the committee members, to ensure that the study findings seemed clear and logical. Reflections and field notes were helpful in the understanding and interpretation of the data

Results

The participants' demographic data were analysed and are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | n | % |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 years | 0 | 00 |

| 25–30 years | 4 | 40% |

| 31–35 years | 2 | 20% |

| 36–40 years | 2 | 20% |

| 46–50 years | 1 | 10% |

| 51–55 years | 1 | 10% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 6 | 60% |

| Unmarried | 4 | 40% |

| Professional qualification | ||

| Midwifery | 8 | 80% |

| Midwifery and lady health visitor | 2 | 20% |

| Academic qualification | ||

| Matriculation | 4 | 40% |

| Intermediate | 2 | 20% |

| Bachelors in arts (BA) | 2 | 20% |

| Bachelors in science | 1 | 10% |

| Masters in Islamic studies | 1 | 10% |

| Experience | ||

| 5–<10 years | 5 | 50% |

| 10–<15 years | 2 | 20% |

| 15–<20 years | 2 | 20% |

| 20–30 years | 1 | 10% |

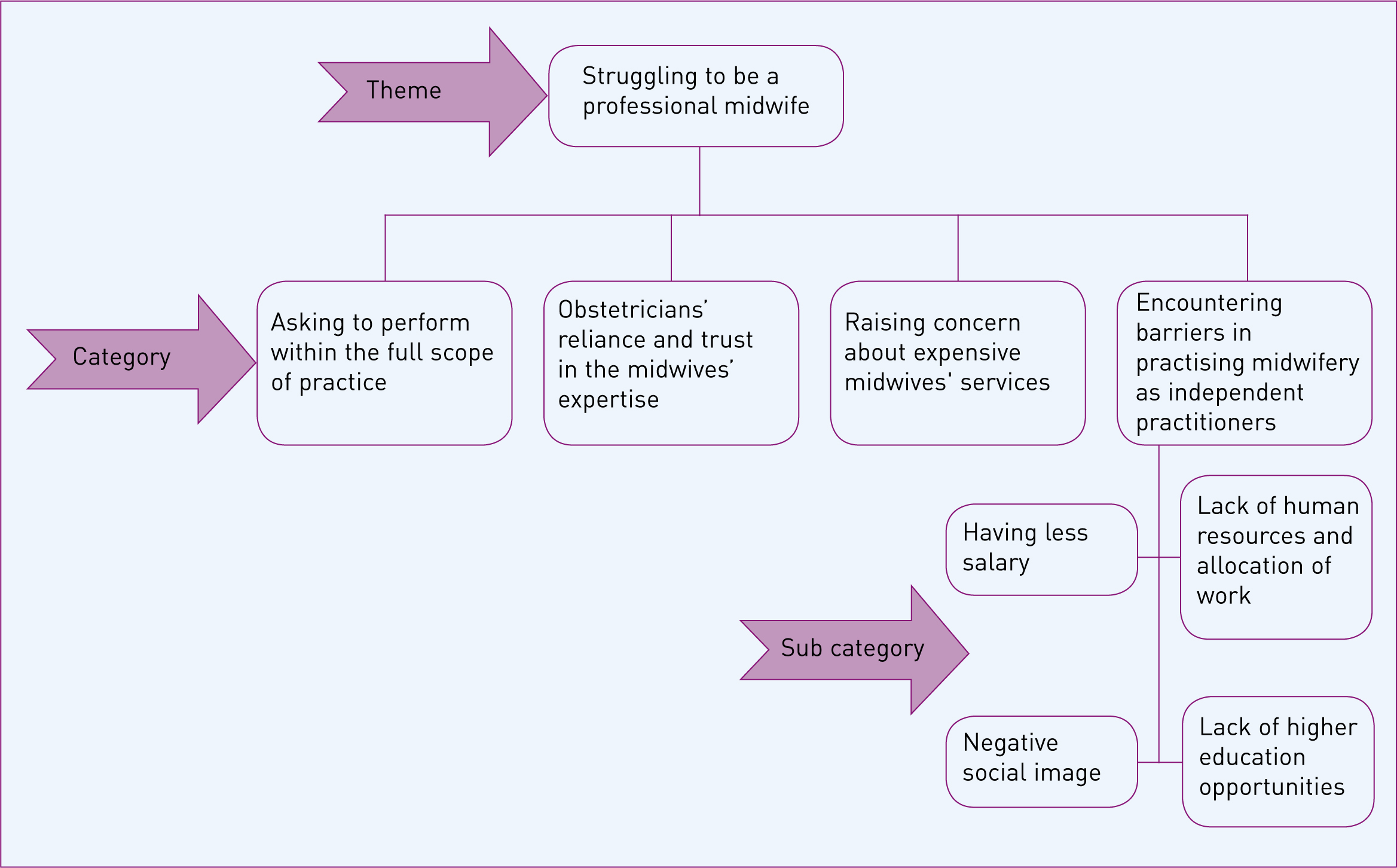

After an in-depth analysis of the participants' interviews, one theme (‘struggling to be a professional midwife’) and four related categories emerged from the data. The related four categories were:

Theme: ‘Struggling to be a professional midwife’

Generally, all of the midwives reported that they were struggling to perform their role in a way that encompassed their full scope of practice. They were asked for recognition of their professional roles. Although they were professionally trained and licensed for midwifery practice, their institution's rules and regulations limited their scope of practice. Participants said that their competency and expertise were being acknowledged and trusted by the obstetrician; however, they struggled for their personal identity as a professional independent midwife. Sultana stated that:

‘Being a midwife, I want the institution to have a system where the [women] would come for registration by giving our names personally. There should be a status of the midwife where we could provide maternity care independently.’ (Sultana, maternity site two)

Struggling to provide the full scope of practice, Sakina shared her experience:

‘Now during intrapartum period, RMOs (junior obstetricians) even they are new, conducting deliveries and we [midwives] are assisting the RMOs. Some years earlier, we [midwives] were providing care to the patient [women] during their antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods, at that time we felt happy.’ (Sakina, maternity site one)

Sharing their struggle, the participants reported that a lack of opportunity for higher education in midwifery was one of the factors that hindered them from remaining midwives:

‘There is not so much value of midwifery in Pakistan, so continuing education is necessary. Therefore, I have planned to change my track into nursing and, for the long term, I am planning to do a Masters of Sciences in Nursing.’ (Kiran, maternity site one)

Based on the participants' perceptions it was evident that they faced several challenges in practising midwifery-led care as professional midwives.

Category 1: Asking to perform within the full scope of practice

Midwives are trained and licensed to conduct deliveries independently, but the study findings revealed that this was not happening. In the past, midwives were allowed to conduct deliveries independently; however, for the last 6 years, the scope of practice for midwives in the same facilities has been limited to assisting the doctors during their obstetric practice. Comparing the past and present practices, Sakina, the most senior midwife, who has experience of conducting more than 1000 births stated:

‘Previously, when women were registering for nursing care [means birth was conducted by midwives], the rate of [caesarean] section was very low. At that time women considered nurses [midwives], more experienced to conduct and manage deliveries … Previously, I was independently delivering patients [women] but now the practice has been restricted.’ (Sakina, maternity site one)

A number of participants reported that they were working in antenatal clinics but were not permitted to practise to their full scope as a midwife:

‘Here [in the facility where the participant was working] we [midwives] are not working fully independently; we are working under the supervision of our instructors [obstetricians]. We practise whatever is suggested and done by the obstetrician.’ (Kiran, maternity site one)

Category 2: Obstetricians' reliance and trust in the midwives' expertise

Almost all the participants indicated that obstetricians and junior obstetricians have trust in, and rely on, midwives' expertise, skills, and knowledge but still they are struggling to perform their practices independently:

‘Sometimes if new and inexperienced RMO was on duty, then the consultants want midwives to examine the patients and share the findings, on the basis of that they the plan care.’ (Roshan, maternity site one).

Sakina the experienced participant shared her experience:

‘The consultant told RMO “Give the phone to the midwives present there” … Then the doctor would ask us, “Okay Sister what is your expert opinion about it?” on the basis of assessment we guide them about women condition.’ (Sakina, maternity site one)

Category 3: Raising concern about expensive midwives' services

The participants of the study raised the concern that in their facilities, the services for midwife cases are expensive:

‘Nurse [midwives'] cases are expensive nowadays, and patients [women] have to pay 7500 rupees in a package for a nurse case. Though we provide great quality care but the patients cannot afford to pay so much money a nurse [midwives'] case.’ (Mehwish, maternity site two)

Sultana shared her experience of working previously in midwife-led care:

‘Before 2 to 3 years we [midwives] had a lot of nurse cases here; we used to have 7 to 10 deliveries every night [in this facility]. But now we see that fewer patients [women] come here for normal delivery. On inquiry they said they cannot afford hospital's charges.’ (Sultana, maternity site two)

Category 4: Encountering barriers in practising midwifery as independent practitioners

Four sub categories emerged from this category, which hinder midwives to practise autonomously, leading to demotivation dissatisfaction with their jobs. These sub categories included: low salary, a negative image in the society, lack of human resources, and lack of opportunity for higher education in midwifery. For example, most of the participants reported that in relation to their workload and demands of the profession, they were not paid enough:

‘The hospital management does not count our [midwives] experience as such; they do not give appropriate salaries to us. We are getting the same salaries as the NA [nursing assistant] and other junior staff, so what's the use of getting so much expertise in this field?’ (Noorein, maternity site one)

All the participants from maternity site one reported that lack of human resources and the increased workload made them feel stressed and frustrated:

‘Mostly we [midwives] are alone in the labour room … One midwife is responsible for receiving the baby, having to answer to the gynae doctor [obstetrician], and if the baby gets serious, then we also have to give answers to the paeds [paediatrics] doctor. At times it is not possible for just one person to perform all these duties.’ (Noorein, maternity site one)

Some of the participants shared that midwives are generally perceived as Dais (traditional birth attendant) or assistants to doctors. In comparison to the nursing profession, society views midwives as having less knowledge and qualifications:

‘There isn't any image of midwife in the eyes of other people; there is more value placed on RNs [registered nurses] in our society.’ (Noorein, maternity site one)

Verbalising her feelings, Zohra said that society does not recognise midwifery as a profession; only their family knows how a midwife works professionally. She stated:

‘Society does not have a good image of a midwife; people don't like a midwife. Only our family members and relatives know who we are … Only one Muslim community group, they really like the midwives and the nursing profession.’ (Zohra, maternity site two)

A few participants reported that due to the lack of opportunities for higher education in midwifery, they were planning to change their track from midwifery to nursing. Mehwish was waiting for a higher education programme in midwifery:

‘A few days ago I heard about the commencement of a bachelors programme for RMs [midwifery], so I have a plan to apply in it, but I do not know whether it has started or not. But yes, I have a plan to apply for it.’ (Mehwish, maternity site two)

Discussion

The study explored midwives' perceptions about practising the midwifery-led care model. The study identified midwives struggling to be acknowledged as a professional. This finding is consistent with the literature from both developed and developing countries that reveal most midwives around the world are struggling for their professional identity (Brodie, 2002; Lavender and Chapple, 2004; Iyengar and Iyengar, 2009; Larsson et al, 2009). This is mainly because of the dominance of the obstetric model, which has meant that midwives' professional roles and credibility are often undermined. Midwifery training facilitates midwives to become autonomous and independent practitioners who provide care to women during the birth continuum. This way of working supports a reduction in maternal and neonatal mortality (ICM, 2010a; WHO, 2010). In order to be qualified as a midwife, guidelines of the PNC require midwifery students to perform a minimum of 10 independent births (PNC, 2003). However, the midwives in this study cannot practise within the full scope of their competencies, therefore this standard is unlikely to be achieved and may not be sufficient for midwives to develop competence and confidence. Consequently, midwives in both sites of this study work as assistants to obstetric consultants to provide care to women during the antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal periods. These findings are consistent with other studies from the developed world, such as in Australia and England, (Brodie, 2002; Lavender and Chapple, 2004) and from the developing world, such as in India (Iyengar and Iyengar, 2009).

This study emphasised that midwives felt competent and confident to provide skilful maternity care to women during the childbirth process. These midwives were also role models for midwifery students and novice midwives in clinical settings. The study findings also supported that obstetricians trusted and relied on their expertise as midwives. However, midwives felt devalued and undermined. A few participants shared their feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction. Similar findings were reported in earlier studies conducted in England and Sweden, which revealed that due to increased medicalised care, midwives' expertise of maternal and child health care were declining (Lavender and Chapple, 2004; Larsson et al, 2009). This created a shortage of experienced midwives to act as mentors for junior midwives and students, which is further exacerbated by retirement. It must be highlighted that in Pakistan there are institutions that provide opportunities for midwives to be independent practitioners, which supports the provision of a full scope of maternity service (Shahnaz, 2010, unpublished).

Reflecting on their experiences, participants raised the concern that the absence of higher education in midwifery created no opportunities to advance their career. The link between higher education, professional growth and career progression in midwifery is intrinsic. The ICM (2010b) has also emphasised that higher education for midwives should increase their ability to provide evidence-based practice to women in any setting. In the UK, midwifery education consists of degree, and optional postgraduate programmes (NHS, 2015). Internationally, midwives having achieved higher level qualifications enter senior management, lead research, and influence policy making. Thus, higher education will not only improve standards of care, level of competency and career structure, but also strengthen midwifery roles and raise the profile of midwifery.

Accessible and cost-effective maternal and child care is the one of the main components of the midwife-led care models by enhancing availability of skilled birth attendants to the women during the birth continuum. In Pakistani culture, the decision to invest money in seeking maternal and child health is considered less important than investing in other household resources, due to gender inequalities and the distribution of resources (Ghani, 2005; unpublished). This would lead to women using unskilled birth attendants called Dias, which seem cost-effective, but are known to increase MMR and NMR. According to the women in the study, the available midwifery services in these facilities seem expensive: i.e. Rs 8000–9000 for normal vaginal compared to other facilities which charged Rs 2000–3000 for birth. Therefore, to increase the access to skilled birth attendants, it is essential for policy makers to consider the cost of such services and improve MMR and NMR. Rasool (2010; unpublished) similarly reported that women prefer traditional birth attendants (Dais) for their childbirth process because of their lower costs. However, while traditional birth attendants may charge lower basic fees, higher in-kind costs are paid. In-kind costs equate to additional livestock (chicken, cow, and sack of rice), clothes, and jewellery (Edwards et al, 1989) given to the Dai. The study highlighted that insufficient vision and lack of awareness about midwifery services leads to low numbers of women booking midwifery-led care. Even in-service sessions, called ‘open houses’, conducted to create awareness about professional roles in an organisation do not focus on the role of the midwives as independent practitioners. Brodie (2002) in her study conducted in Australia also identified a lack of awareness and recognition among the community as the main barrier to an autonomous professional midwifery identity. As a recommendation, advertising may be key to raise awareness about midwives' autonomous role among society. Therefore, policy leaders need to allot finances to promote visibility of midwifery-led care in Pakistani society.

Limitations

Participants in this study were from the private hospital, and so the results may not reflect the practices of midwives in government hospitals. Hence, there is a need for further research to explore perceptions of midwives working other settings.

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative descriptive study in Pakistan which explored midwives' experiences and perceptions about the midwifery-led care model. The findings reveal that midwives struggle to practise independently and autonomously while providing maternity care to women during the antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal periods. Moreover, it was found that midwives felt fully competent and could demonstrate their expertise of skills and knowledge with respect to providing quality care to women during the childbirth continuum.