Cultural understandings of fatherhood have changed substantially over the last several decades (Lamb, 2000; Selin, 2014). In the UK, there has been a move for fathers to be more involved as nurturing co-parents, being present at antenatal classes and birth, and sharing responsibilities involved with child-rearing, domestic duties, and maintaining family life (Henwood and Proctor, 2003). In recognition of fathers as primary carers, the UK government has implemented a shared parental leave policy (Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy, 2018), and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence ([NICE], 2012) recommend that practitioners should ‘focus on developing the father-child relationship as part of an approach that involves the whole family’.

However, despite shared parental leave now being available, take up of this option has been very low. Birkett and Forbes (2019) suggest a variety of reasons for this low take-up. From extensive interviews with both fathers and mothers, they identified reasons for low uptake ranging from financial constraints (enhanced rates of parental pay are rarely available within the shared leave but are often available to mothers) to cultural reasons (the current emphasis on the importance of breastfeeding in particular was seen as a barrier to fathers taking up leave). In addition, the information and access to support for finding out about shared leave was often poor and had to be applied for through the mother's leave policy (the authors also identified issues with maternal ‘gatekeeping’ of the leave).

Importance of father involvement

Since being termed ‘the forgotten contributors to child development’ (Lamb, 1975), research has increasingly recognised the positive contributions of father-involvement to children's psychological, behavioural and cognitive development (Sarkadi et al, 2008; Wilson and Prior, 2011). Often common in father-child relationships is competitive and physical play which a recent meta-analysis suggests has positive associations with children's emotional development, self-regulation and social competence (StGeorge and Freeman, 2017). Children with secure attachments to both parents exhibit better personal, social and cognitive development (Lieberman et al, 1999; Beardshaw, 2001).

Fathers' vulnerabilities to psychological distress

As with mothers, the emotional upheaval of parenthood can increase vulnerability to psychological distress in fathers: in a large review of fathers' role and involvement in the perinatal and birth period, Burgess and Goldman (2018) review fathers' mental health during this period. They identify studies that used the data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children which looked at father mental health during this period which suggested that 4% were considered to be moderately depressed and 2.3% severely depressed. More recent data quoted by the review (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2017) reported that 12 % of mothers who were asked, said that their partners were currently experiencing mental health problems. The large variety in reported paternal depression between studies may be in part due to a problem with how this is assessed because often parental depression is assessed using criteria from maternal depression, and there is some evidence that there may be important differences, such as father postnatal depression building up more slowly than maternal depression (Areias et al, 1996).

It is also possible that men who witness the birth of their child may go on to suffer with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This hypothesis was tested in a study by Bradley et al (2008) who found that there were some symptoms of trauma amongst fathers (particularly around hyperarousal) but that no men reported fully symptomatic PTSD (though 8% did report clinically significant scores on depression). However, there was a drop-out rate of 40% between those who completed the first questionnaires and went on to complete the trauma questionnaires, so it is possible that those who dropped out might have reported higher symptoms.

Worryingly, there is also a high correlation between father and mother's depression with studies suggesting correlations between 24%–50% between maternal and paternal depression and there is evidence that an infant's development is more affected by two parents being depressed (Paulson et al, 2006).

The high correlation between parents' depression may explain why the ‘buffering’ effect of fathers on their infant's development when a mother is depressed is not more commonly observed. Goodman (2008), for example, observed that partners of women who were depressed had poorer interactions with their children than partners of non-depressed women giving some suggestion that the stress from having a depressed partner might also affect fathers' relationship with their children.

There are many reasons why fathers may struggle during the perinatal period: new fathers can struggle with sleep deprivation, psychological reorganisation of the self, and relationship changes with their partner, social networks and baby (Genesoni and Tallandini, 2009; Darwin et al, 2017).

Fathers have also reported feeling unprepared when transitioning to parenthood having not learnt suitable parenting skills from their own fathers (Condon et al, 2004) with consequences for father-infant bonding (Fletcher, 2011). Financial burdens that babies bring may increase pressure on fathers to earn money, resulting in greater likelihood of their isolation from mother and baby (Kim and Swain, 2007). Difficulties balancing personal and work-related pressures with the new parental role can be highly stressful (Genesoni and Tallandini, 2009). Additionally, with mothers increasingly returning to work following maternity leave, and fathers expected to be more involved in childcare, fathers may feel conflicted between sociocultural roles and expectations of what it means to be a ‘father’ and a ‘man’ (McBride et al, 2005; O'Brien, 2005; Wee et al, 2013).

Culturally, although masculine ideals vary according to time and place, dominant western ideals have traditionally assumed men are stoic, self-reliant, providers and protectors (Hunter et al, 2017). Societal pressures for men to conform to these ideas around masculinity are suggested to contribute to psychological distress and increased suicidal behaviours in males (Emslie et al, 2006; Cleary, 2012). In fathers, masculine norms have been associated with reluctance to seek psychological help due to feeling they should appear strong and prioritise the mothers' psychological needs (Williams, 2007; Colquhoun and Elkins, 2015; Rominov et al, 2017).

Paternal mental health and the family

Although not always the case, research suggests that fathers experiencing psychological problems can demonstrate impaired parenting behaviours and interactions with their infants, such as under stimulation, insensitivity, emotional and physical unavailability and, in rare cases, child maltreatment (Wilson and Durbin, 2010; Cleaver et al, 2011; Giallo et al, 2015; Sethna et al, 2015; 2018). Disengaged father-child interactions and paternal depression is associated with increased likelihood of poor father-infant attachment (Buist et al, 2003), and behavioural and emotional problems in children (Kane and Garber, 2004; Ramchandani et al, 2005; 2008; 2011; Ramchandani and Psychogiou, 2009; Kvalevaag et al, 2013).

Partners of depressed men can also be affected. For example, women who report lower partner support have a greater risk of postpartum depression (PPD) (Dennis and Ross, 2006). There is also a suggestion that the link between paternal depression and infants' later behavioural problems is in part mediated by an increase in hostility between parents (Hannington et al, 2012) and by a decrease in marital satisfaction (Cummings et al, 2005).

In contrast to the above research, good paternal mental health can have a positive effect on the family. For example, positive father involvement can be protective for mothers' wellbeing (Whisman et al, 2011). Fathers are often the first to notice psychological distress in the mother, sometimes before the mother herself (Russell et al, 2013). Women hospitalised for PPD tend to have shorter stays if they have a supportive partner (Grube, 2004). Additionally, when mothers experience psychological distress, there is some suggestion that fathers who are ‘well’ can buffer against potentially negative consequences for the child (Mezulis et al, 2004). Children who had depressed mothers but reported positive relationships with their fathers were also shown to not struggle with the same child behaviour problems as those without positive paternal relationships (Chang et al, 2007)

Do fathers get appropriate support?

UK policies are responding to the increasing focus on ‘involved fatherhood’ by advocating for the inclusion of fathers throughout the perinatal period (Royal College of Midwives, 2011). NICE (2006) guidelines recommend perinatal services ‘offer fathers information and support in adjusting to their new role and responsibilities within the family unit’. However, fathers have reported lacking support from NHS perinatal staff when they needed it most (Machin, 2015).

UK research suggests that many fathers are keen to be equally involved but often feel pushed into traditional roles by societal norms, policies, structures and healthcare professionals' (HCPs) attitudes, leaving them feeling like a ‘secondary’ parent (Deave and Johnson, 2008; Steen et al, 2012; Machin, 2015). Perinatal services tend to be mother-centred, and lack father-specific support, which can deter fathers from help-seeking (Colquhoun and Elkins, 2015; Rominov et al, 2017). Overall, these findings suggest that traditional social attitudes persist, whereby fathers may feel ‘relegated to the position of providing support for the mother, rather than having their own role to play’ (Barrows, 1999).

Rationale and aims for the current study

Given the increased risk of paternal psychological distress, and the negative associations with child, couple and maternal outcomes (Kane and Garber, 2004; Giallo et al, 2013), prevention and early intervention regarding fathers' wellbeing is important for all family members. The transition to parenthood has been highlighted as a high-impact area where midwives and health visitors can make significant differences to parental wellbeing (Department of Health and Social Care, 2014; Philpott, 2016). However, it has been stated that ‘maternity and mental health services do not provide fathers with information and support, despite the wider benefits that this would have for families' (Hogg, 2013). Although previous studies have interviewed and researched fathers' experiences of perinatal services, there has been no previous attempt in the literature to amalgamate practitioners' and fathers' views to achieve a consensus across groups in order to identify strengths, weaknesses and possible changes for father inclusive practices to happen. This leads to the following research aims:

- To understand areas of consensus between HCPs and fathers of the most important issues that need addressing in early fatherhood

- To identify areas of disagreement between HCPs and fathers, and to attempt to understand this gap theoretically

- To explore fathers' and HCPs' ideas for improving paternal perinatal support.

Method

Design

A three-round Delphi method (Dalkey and Helmer, 1963) was used to form collaboration among fathers and HCPs. With the rationale that ‘n heads are better than one’ (Dalkey, 1972), the Delphi method involves two or more rounds of data collection from respondents with real-world knowledge in an area, and encourages consensus-building by sharing feedback among responders (Hsu and Sandford, 2007).

Qualitative and quantitative methodologies were used across the consensus-building process. Qualitative data from open-ended questions at round one (R1) focus groups were developed into statements. Statements were fed back in a round two (R2) online survey to more participants, asking them to rate their agreement with the statements. In round three (R3), previous R2 participants received individualised surveys comprising the same statements, with each statement displaying their R2 response and the average response from all participants. Participants were invited to re-rate statements in light of the groups' responses, with the aim to clarify consensus and divergence of ‘expert’ opinions (Hasson et al, 2000).

Participant recruitment

Taking ‘expert’ to include ‘any individual with relevant knowledge and experience of a particular topic’ (Cantrill et al, 1996), fathers and HCPs were recruited for their expertise of parenthood and of receiving or providing perinatal services. Table 1 shows participant inclusion criteria. Fathers did not need to be first-time fathers but had to have a child under three years old.

Table 1. Participant inclusion criteria

| Fathers | Health visitors and midwives |

|---|---|

| Fathers with a 0−3-year-old biological child born in London using NHS services (did not need to be first child) | Qualified and in post with London NHS services for at least six months |

| Fathers who were involved during the pregnancy, birth and postnatal year | Have had at least some contact with fathers to reflect on |

| Able to speak and read English |

Recruitment was carried out by the first author and various recruitment strategies were employed at each round in efforts to acquire representative samples. For the first round, both fathers and HCPs were recruited in one south London borough where the third author worked and was able to provide contacts to perinatal services and children's centres. However, this method did not yield enough participants for the second round, so further NHS trusts were approached, and six agreed to take part. HCPs in the participating trusts were contacted by the first author writing to all managers in perinatal services and, where permission was given, team meetings were attended and emails sent to recruit to the second round. As fathers proved difficult to recruit directly through services, further ethics revisions gave permission for participants to be recruited through social media and personal contacts. This method of recruitment eventually resulted in a larger enough numbers of participants, but may have resulted in a lack of diversity. Table 2 summarises participant demographic information for both fathers and HCPs.

Table 2. Participants demographic information

| Demographic information: healthcare professionals | Round 1 (N=5) | Round 2 and 3 (N=22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: | 18−2425−3435−4445−5455−64 | --221 | 19372 |

| Gender: | Female | 5 | 22 |

| Ethnicity: | WhiteBlackMixed ethnicityAny other ethnic group | 41-- | 17221 |

| Profession: | MidwifeHealth visitor | 23 | 148 |

| Length of time in role: | MeanRange | 9.7 years2.5−18.2 years | 8.3 years2−28 years |

| Frequency of contact with fathers at work: | As often as mothersAlmost as often as mothersHalf as often as mothersRarely | 113- | 38101 |

Ethics

This study received approval from a Research Ethics Committee, Health Research Authority and local NHS R&D departments. The British Psychological Society Code of Ethics and Conduct (2009) was followed throughout. Participants received information sheets detailing the research, risks, participant rights, confidentiality, and resources for help and support. Participants were allocated individual participant numbers to maintain anonymity and were informed that their anonymous responses may be shared with other participants, including future publications. Written informed consent was obtained before participation and a debrief provided following each round.

Quality assurance and reflexivity

Before data collection, the researcher undertook a ‘bracketing’ interview to reflect on potential influences of her personal context, subjectivity, and biases regarding the topic (Finlay and Gough, 2008). Maintenance of a research diary improved dependability of decision-making during the Delphi process (Borg, 2001).

Measures

The researchers developed R1 focus group schedules to meet the research aims. Questions designed to measure participant demographics, contextual information, and fathers' exposure to parental stressors were also given at R1 and R2. Each online survey was developed based on the previous round (described further below) and distributed using online survey software.

Data collection and analysis

The three-round Delphi process took six months between August 2017 and February 2018. This section describes the data collection and analysis procedures according to the three rounds.

R1 focus groups

The researcher facilitated two, approximately 90-minute focus groups; one with HCPs and one with fathers. Semi-structured protocols were designed to encourage participants to talk about their views regarding the research questions and were applied flexibly to allow participants to take discussions in their desired directions within the topic. For example, a question in the father's group was: ‘how was the transition to fatherhood once your baby was born?’ and in the HPCs group: ‘do you feel that mothers and fathers have different needs? What are the differences?’

R2 online survey

R1 data were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This method was chosen as it allowed for flexibility in the identification of both theory driven and data-driven codes, and used both inductive and deductive processes in analysis (Booth and Carroll, 2015). Thus, data could be explored using previous knowledge as well as new themes being allowed to emerge.

The first author analysed the data by ordering data extracts into codes and then grouping the codes into themes and subthemes. These themes were reviewed for initial face validity by the second and third authors (if the themes represented their clinical knowledge of the area). Further quality assurance was carried out by grouping data extracts and presenting these to a colleague (uninvolved in the project). Codes and subtheme titles were randomly organised in another document. The colleague was asked to match the codes and subthemes to the grouped data extracts. This process resulted in an inter-rater agreement of 90% for father data, and 85% for HCP data, which is sufficient according to Miles and Huberman (1994). Minor changes to codes and sub-themes were made in the process of consulting between authors and in consultation with the second-rater.

Statements were then devised according to the codes to reflect participants' qualitative responses, using their words where possible. With the aim of gathering consensus between groups, all participants needed to complete the same R2 online survey, therefore themes from the two focus groups were collapsed to form six final themes (Table 4). The 82 statements relevant to the themes were stated in a neutral way to be relevant to fathers and HCPs. A total of 14 additional statements were deemed too specific to HCPs' experiences so were only presented to HCPs. Participants were asked to rate statements on a six-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ and invited to leave comments upon completing each section. The survey took approximately 25 minutes and was online for 30 days.

R3 online surveys

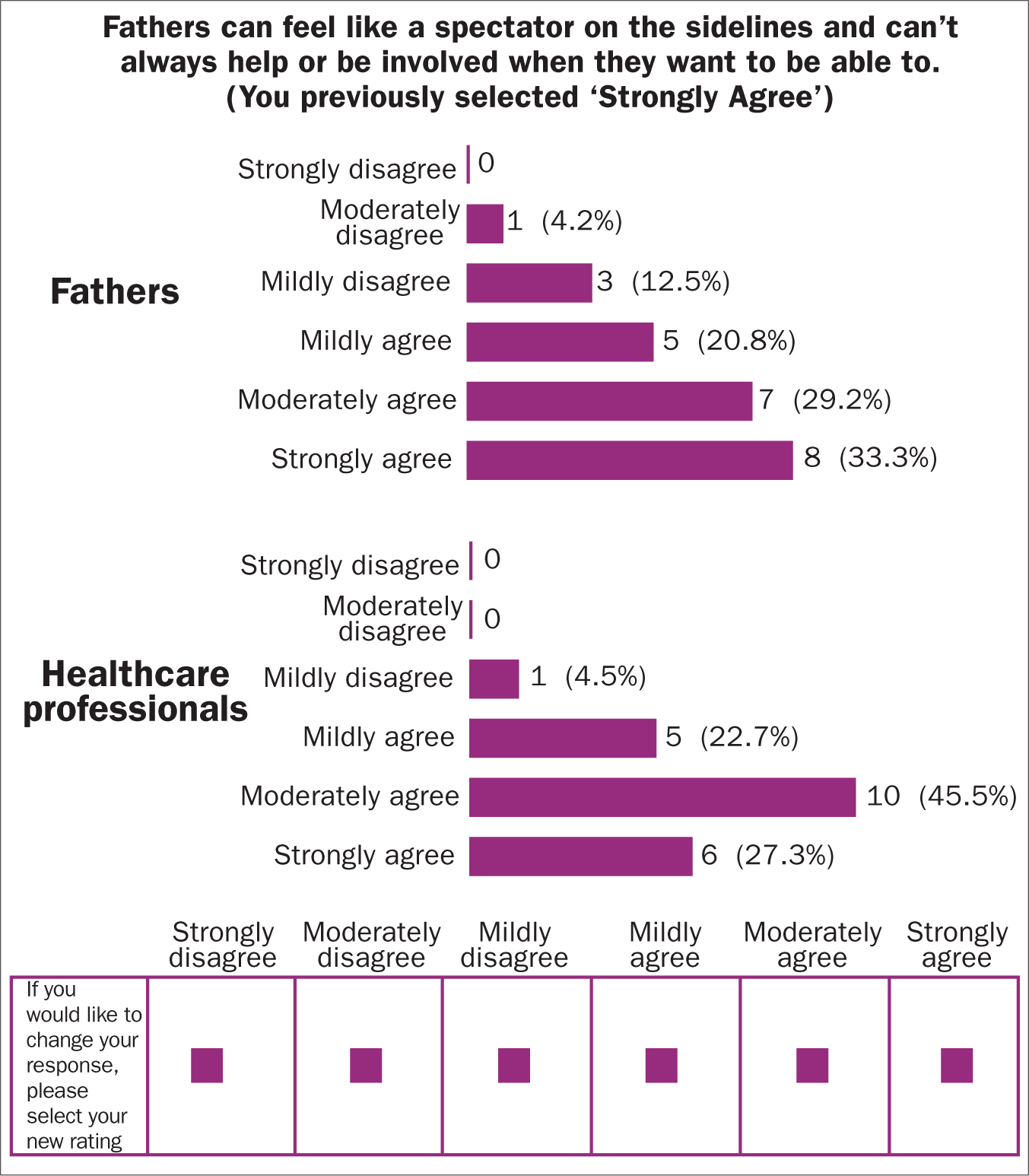

R3 had the same statements as R2, except for statements which already reached ≥75% consensus for both groups. R3 surveys were individualised for each R2 participant, so that each statement was presented with the participants' previous response, and both groups' overall responses (see Figure 1). Qualitative R2 comments were anonymously presented at the top of each section to allow participants some further context to the responses. Participants were invited to consider both groups' ratings and comments and then re-rate their previous responses if they wished.

Figure 1. Example of an individualised R3 survey statement

Figure 1. Example of an individualised R3 survey statement

Quantitative analysis of consensus and divergence

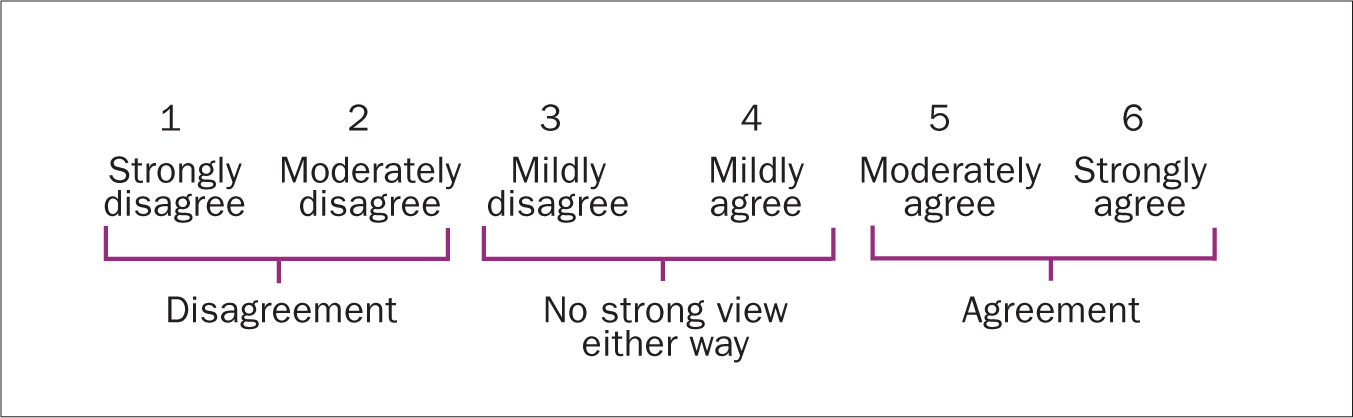

Following data collection, the six-point Likert scale was collapsed into three categories to indicate participants' disagreement or agreement to statements, as shown in Figure 2 and in line with other studies (South et al, 2015). Only strong or moderate views are presented in the results, in line with the research aims. Percentages of disagreement (sum of percentage of participants selecting one and two) and agreement (sum of percentage of participants selecting five and six) were calculated for each statement, separately first for fathers and HCPs, to get within-group consensus percentages, then for both groups together to calculate overall consensus per statement.

Figure 2. Collapsed categories of Likert scale ratings

Figure 2. Collapsed categories of Likert scale ratings

Consensus categories are variable across Delphi studies, with no consensus levels agreed thus far (Hsu and Sandford, 2007). This study chose, in advance, to operationalise strong consensus as over 74%, as this is a midpoint between the 70%–80% cited in other papers (such as Bisson et al, 2010 and Berk et al, 2011). Following other Delphi studies (such as South et al, 2015), less than 50% agreement was used to define a lack of consensus. The remaining 50%–75% was halved to categorise weak and moderate consensus.

Key Points

- The importance of fathers in infant development is well-established in the literature

- A significant proportion of fathers struggle with poor mental health

- There is a high correlation between mothers and fathers' depression

- Poor paternal mental health can be linked to poor attachment in their children

- Perinatal practitioners can be an important link for fathers in supporting them to seek help

- Unfortunately, perinatal services are poorly set up to offer support for fathers

- This research explores consensus between fathers and perinatal clinicians on how best to support fathers

CPD reflective questions

- What procedures in your service are inclusive or not of fathers?

- What are your experiences of fathers with mental health issues?

- What are the equality and diversity issues that might be relevant in considering fathers' ability to be involved with their infants?

- What implicit or explicit belief do you hold about fathers which might affect how you work with them?