Haemorrhage problems have become the leading cause of maternal mortality, with the rate at 27% in developing countries (World Health Organization et al, 2015). Postpartum haemorrhage can occur in the first critical 24–48 hours after birth (Cabero-Roura and Rushwan, 2014). A total of 11.4% of postpartum complications in Indonesia include bleeding in the birth canal, discharge from the birth canal, swelling of the hands and face, headaches, convulsions, fever for more than 2 days, swollen breasts and hypertension (Banlitbangkes, 2019). In addition, postpartum complications may cause psychological problems, such as anxiety, potentially leading to postpartum depression (Shahar et al, 2015). However, many postpartum mothers in Indonesia (50.1%) do not know that this can be a problem; therefore, they do not seek help (Banlitbangkes, 2019).

To overcome the issue of postpartum complications in mothers, cultural biopsychosocial assistance, information and support are needed (Wiklund et al, 2019). Indonesia has a cultural diversity inherent in everyday life and healthcare and culture-based postpartum maternal care is required (Banlitbangkes, 2019). Nurses play a role in facilitating family-orientated motherhood, including continuity, participation, mothers' adaptation, consistency, information and preparation for childcare (Wiklund et al, 2019) with a cultural approach (Hodikoh and Setyowati, 2015). In the present study, a transcultural-nursing theoretical framework was used. This framework provides nursing services with consideration for the local culture of postpartum women and their families. Cultural aspects include values, norms and ways of life that guide people to think, decide and act in certain ways (Leininger, 2001; Andrews and Boyle, 2002). Nursing care should be adjusted to the procedures, customs and traditions of the community, as long as they do not conflict with health principles (Alligood and Tomey, 2014).

Culture-based care among postpartum mothers can reduce physical and psychological problems (Coast et al, 2014; Aragaw et al, 2015; Jones et al, 2017; Aryastami and Mubasyiroh, 2019). Mothers' methods of handling postpartum complications cannot be separated from their habits and family culture (Setyowati and Rosnani, 2019). One intervention used is warm therapy with sun exposure (phototherapy) (Judistiani et al, 2019). Innovations have been developed with infrared, which can stimulate action potential, affect the pulse, have an impact on the wound healing process and reduce oedema (Tsai and Hamblin, 2017). Regeneration in the nerve cell network can reduce pain. Infrared with the optimal wavelength, or a combination of different intensities and durations, results in melatonin production. Therefore, light can stimulate mood and memory and improve cognitive function (Kemper, 2018). Near infrared with a wavelength of 760–1400 nm can provide a heat effect on the skin. Near infrared is low-level light therapy or photobiomodulation (Barolet et al, 2016).

The data show that near infrared can provide benefits in terms of both physical and psychological conditions. Thus, this study aimed to develop culture-based postpartum interventions using photobiomodulation near infrared technology for its impact on maternal physical and psychosocial adaptations.

Methods

Design

A research and development study was conducted. Research and development is a wide category that encompasses the activities of fundamental research and applied research and development. Research and development is often referred to as ‘innovation’. It involves systematic activities that aim to enhance knowledge while also allowing for the application of that knowledge in the development of new goods, processes and services (Kainulainen, 2014). In this study, research and development consisted of three stages. The first stage used a qualitative phenomenological design. Phenomenology was chosen because it illuminates the experience of an individual during a phenomenon, in this case, postpartum women's lives (Afiyanti and Rachmawati, 2014). The second stage was developed using sensitivity and specificity tools in the laboratory, and these tools were tested on adult women using a pre-experimental study design. In the last stage, a quasi-experimental study was used to implement these tools, which were used by postpartum mothers.

Setting and sample

The study was conducted in Palembang, South Sumatera, Indonesia. The first phase was conducted from June to August 2018, using a qualitative phenomenological study design. This study aimed to explore the experience of mothers, massage shamans and traditional figures in providing care for physical and psychological problems. Massage shamans and traditional figures came from the same area as participant women. A total of 20 participants, consisting of 12 postpartum mothers, four massage shamans and four traditional figures in Palembang, Indonesia participated in this study. The participants were obtained through purposive sampling. The inclusion criteria were postpartum mothers aged 20–35 years old, massage shamans and traditional figures aged 35–70 years old. Participants who could not complete the study process were excluded.

The second stage was conducted from August to November 2019 using a pre-experimental study design without control groups. Based on the data obtained from the first phase, research was undertaken regarding the need to develop tools for use in postpartum therapy. The photobiomodulation near infrared therapy tool was developed and sensitivity and specificity tests were carried out in the laboratory to form a prototype (Figure 1). A therapeutic dose that is safe to use was identified. The sample total was 80 women, recruited through accidental sampling. The inclusion criteria were adult women aged 20–45 years. Respondents who could not follow the study process were not included.

The third stage was conducted from January to March 2020 with a quasi-experimental design. The total sample consisted of 90 respondents recruited through convenience sampling. There were three groups (intervention, control 1 and control 2) with 30 respondents in each. The inclusion criteria were first-day multipara postpartum mothers aged 20–35 years, who had support from their mothers, husbands or families, did not have a mental disorder and did not experience a physical illness or complications because of pregnancy-related diseases (eg pre-eclampsia, postpartum depression). The baby needed to have good suction reflexes, weigh greater than 2500 g and not experience any comorbid diseases, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension.

Data collection instruments

The first stage of the research used interview guidelines made by the researchers, inclusive of their field notes and voice recordings. In the second phase, temperature parameters were measured using a thermometer. Comfort parameters were measured using a comfort questionnaire, where answers were graded on a scale ranging from 0–5 (Maaskant et al, 2016). The photobiomodulation near infrared prototype device consisted of a timer, a dimmer cable, a dimmer, lamp fittings, lampposts and infrared lamps with 100 watts of power. The photobiomodulation near infrared therapy dosage included wavelength, duration, distance, frequency and power.

In the third phase, the researchers examined postpartum mothers' physical adaptations by examining their vital signs with a tensimeter, thermometer and watch. Uterine fundal height was measured using a meter. Afterpain was measured using the Visual Analogue Scale (Hayes and Patterson, 1921). The signs were redness, oedema, ecchymosis, discharge and approximation (REEDA), measured by the REEDA Scale (Hill, 1990). Amount of breastmilk was measured by a breast pump. Psychosocial adaptation was measured using the Self Anxiety Scale (Zung, 1971). Comfort was measured by the Comfort Pain Scale (Maaskant et al, 2016).

Data collection procedures

The first stage, a qualitative study, was conducted using in-depth interviews. Each interview was conducted by three researchers (all with the same views regarding the questions and when the interview should be stopped) with each of the 20 participants. The draft schedule was pre-tested with three postpartum women. Following the pre-test, minor changes were made to the wording of some questions to make the questions clearer. The pre-test provided an opportunity for the interviewers to become familiar with the schedule.

The interview began by building trust between participants and interviewers. This involved introductions, obtaining consent and permission to audio-record the interview and take field notes. Informed consent was given by participants, who signed an informed consent sheet.

The interviews proceeded with the questions: ‘how are you (postpartum women) physically and psychologically after birthing?’, ‘do you believe in the massage shaman's skills?’, ‘in your opinion (postpartum mother, massage shaman and traditional figure), do you wish for the development of a tool regarding postpartum needs?’. Each participant was interviewed for approximately 60 minutes. In addition to recording the sessions, the interviewers took notes of their observations. At the end of each interview, the interviewer repeated what the participants had said to confirm they had accurately understood what the participants had shared. No participants made any changes at this point.

The process was stopped when data saturation was reached and there was no new information gained regarding the questions. The researchers used triangulation and the researcher-based triangulation approach, which use various methods to study a single problem. The triangulation method uses more than one data collection technique to obtain the same data from interviews, such as using an audio recorder and conducting observations using field notes (Heath, 2015). The trustworthiness of the data was established by determining the credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability of the data (Polit and Beck, 2012).

In the second stage, the research included laboratory staff who observed the equipment used, conducted instrument analysis and modifications (duration, distance, frequency and power), used the prototypes and conducted pre-experimental testing. Informed consent was manually signed by each respondent who was willing to participate. The working procedure to use this tool had the mother lying in an oblique position. Infrared light was then pointed at the mother's abdomen (uterus). A 100-watt dose for therapeutic administration was given 40cm away for 15 minutes.

In the last stage, respondents were divided into three groups, namely a photobiomodulation near infrared intervention group, a traditional treatment group and a routine intervention group. Informed consent was manually signed by each respondent if they were willing to participate. On the first day of the intervention, all groups conducted a pre-test to evaluate physical and psychological changes. In the photobiomodulation near infrared group, the intervention used the photobiomodulation near infrared tool (9-day intervention) on days 2–10 for 15 minutes each day, from 40cm away. The tool used 100 watts of power. The physical and psychological changes were evaluated on days 3, 6 and 10.

In the traditional treatment group, the researchers collaborated with massage shamans to conduct the intervention. On the first day, a pre-test was conducted. On days 2, 5 and 8, the participants received traditional massage for 60 minutes by massage shamans. On days 3, 6 and 9, respondents received traditional sauna for 15–30 minutes by massage shamans. On days 4 and 7, respondents received traditional treatment (sitting on warmed bricks and being covered by banana leaves) for 5–10 minutes and were observed by the massage shamans.

Respondents in the routine intervention group received interventions from midwives that collaborated with the researcher. On days 3 and 9, respondents took advantage of clinical midwifery practices. They received antenatal care and medicines, such as antibiotics and analgesics. On day 10, the researcher conducted a post-test in all groups to measure physical and psychosocial changes after the intervention.

Data analysis

In the first stage, the researchers transcribed the interventions verbatim and analysed them using NVIVO to code and categorise. The field notes and recordings were linked based on participants' conditions. Then additional information was included based on observation of the participants' quotes.

Data were analysed using the Colaizzi method (Creswell, 2013). The steps consist of familiarisation with the participants' statements, identification of significant statements, formulation of the meanings of participants' quotes, clustering themes, development of an exhaustive description, production of a fundamental structure and seeking verification of the fundamental structure.

In the second stage, the data were analysed for sensitivity and specificity. Analysis regarding the pre- and post-tests was done using the Wilcoxon test and paired t-test. In the last stage, data were analysed using descriptive analysis to observed frequency distribution, percentage, mean, median, maximum/minimum value and deviation standard. One-way ANOVA was used for normal distribution data. For data that were not normally distributed, the Kruskal–Wallis test was carried out. These analyses were conducted to determine the differences in intervention effects across the three groups over time, with a significance of P<0.05.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Nursing, University of Indonesia (number: SK-07/UN2. F12. DI.2.1/ETHICS. FIK.2020). The Helsinki declaration from the World Medical Association (2013) was used in this research. The participants had the right to freely withdraw and were able to refuse to answer any question that made them feel uncomfortable. In addition, the researchers maintained their privacy throughout the interview. The participants in this study were volunteers, and the study had no possibility of physically or mentally harming the participants.

Results

First stage

Of the 20 participants included in the qualitative study, most were female (75%). The majority of the postpartum mothers were aged 20–30 years (75% of 12 postpartum mothers), massage shamans were aged 50–60 years (75% of four massage shamans) and traditional figures were aged 50–60 years (50% of four traditional figures).

Three themes emerged from the qualitative study: physical and psychological changes, traditional treatments and modification of therapeutic tools, each supported by sub-themes.

Theme 1: physical and psychological changes

After birth, most postpartum mothers experienced physical and psychological changes, which could be postpartum effects. This theme had two sub-themes, the physical and the psychological.

Most of the postpartum women felt changes in their physical condition, such as weakness, pain and dizziness.

‘They complained of weakness, pain in stitches, dizziness and abdominal pain.’

(PM 3)

‘I am afraid to move. So, I just lay on my bed…but I am tired if I have to lay on my bed for a long time.’

(PM 7)

Five postpartum women felt more sensitive and sometimes felt unloved.

‘I feel more sensitive. It's easy to daydream, and I sometimes feel unloved.’

(PM 10)

Theme 2: traditional treatments

This theme explored how postpartum mothers felt regarding traditional treatments. They underwent traditional techniques and ate traditional food to improve their health. This theme had two sub-themes, traditional techniques and traditional food.

Traditional techniques were usually implemented by postpartum mothers who lived in rural areas. They often showered with boiled spices, water and warmed bricks to accelerate wound healing.

‘[I] massaged breasts using a warm cloth, continued to shower with boiled water and spices and smeared eucalyptus oil and lime on the stomach.’

(PM 8)

‘For suture wounds, they usually sit on heated bricks, but they are padded.’

(PM 4)

The massage shamans reported their view that using traditional techniques will improve postpartum mothers' health and decrease the use of chemicals that may affect health in the future.

‘We have implemented traditional techniques for a long time…they have no side effects. Besides that, by using traditional techniques, postpartum women avoid chemical treatments that may cause side effects or infections.’

(MS 3)

Traditional figures also supported the massage shamans' views. They reported that traditional techniques were usually implemented in this area and they never found side effects.

‘This [traditional technique] was implemented for a long time, and I have never found side effects for postpartum mothers. For me, it should be maintained, but it may not be possible if there is a better development in the future.’

(TF 3)

Postpartum mothers and massage shamans believed that food was an important factor to improve health. They usually ate boiled food, avoided fried food and drank traditional herbs.

‘After birthing, I did not eat fried food. I think the oily food will take longer to heal my suture wound. So…I only ate boiled food.’

(PM 7)

‘Traditional herbs are good to increase the immune system among postpartum mothers to prevent infection.’

(MS 1)

Theme 3: modification of therapeutic tools

The postpartum mothers, massage shamans and traditional figures identified that it is possible to modify therapeutic tools for the wellbeing of postpartum mothers. This theme had two sub-themes, ease of use and simplicity and the cultural approach.

The participants reported that they felt modified tools should be easy to use, simple and beneficial for postpartum mothers and massage shamans.

‘If the instrument can be used for heating, it can be used to replace other instruments. Besides that, it is also simpler and easier.’

(PM 3)

‘It could be the instrument to be applied, as long as it provides benefits for the mother.’

(PM 1)

‘If the instrument is good, it will be easy for the public to accept.’

(MS 2)

Traditional figures underlined that the modification should be based on a cultural approach. In their view, it could be implemented for postpartum women if there were cultural aspects to the tool.

‘I think it would be better if the modification was based on a cultural approach because that would make it acceptable to postpartum women. Besides, it can be the identity of this area.’

(TF 1)

Second stage

Based on information from the qualitative study regarding the development of tools to treat postpartum women, a tool was developed that was easy to use, simple and beneficial to accelerate the healing of postpartum women: photobiomodulation near infrared. The tool was developed based on infrared light (Figure 1).

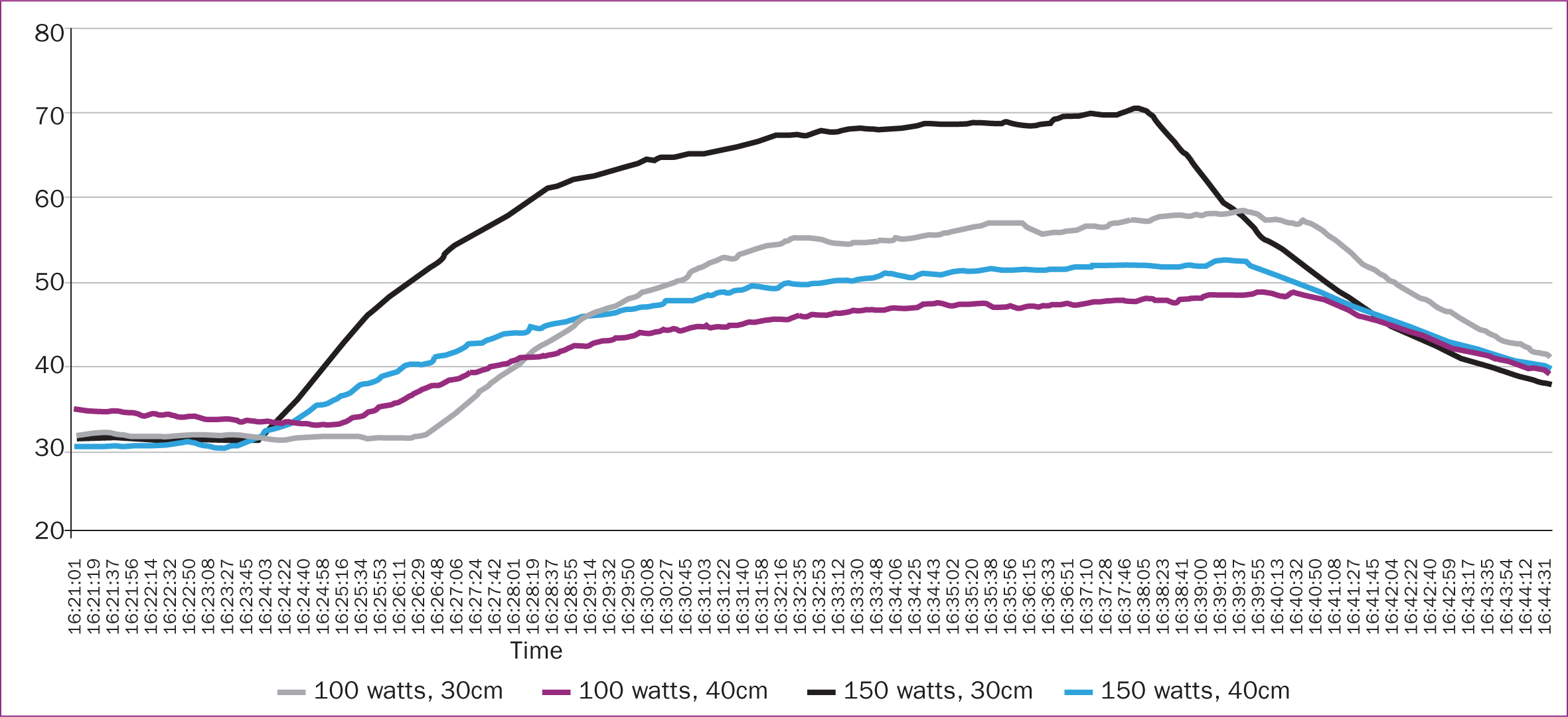

The prototype device was trialled in the laboratory. It was tested by comparing 100 and 150 watts of power with temperature changes at distances of 30 and 40cm (Figure 2). At 30cm with a power of 150 watts, the temperature of objects increased to 70°C, while 100 watts increased the temperature to 60°C. At 30cm with power of 150 watts, the temperature increased by more than 50°C, while 100 watts increased the temperature by up to 50°C. These temperature changes are very high for the normal human body. A second test was carried out with power of 100 watts.

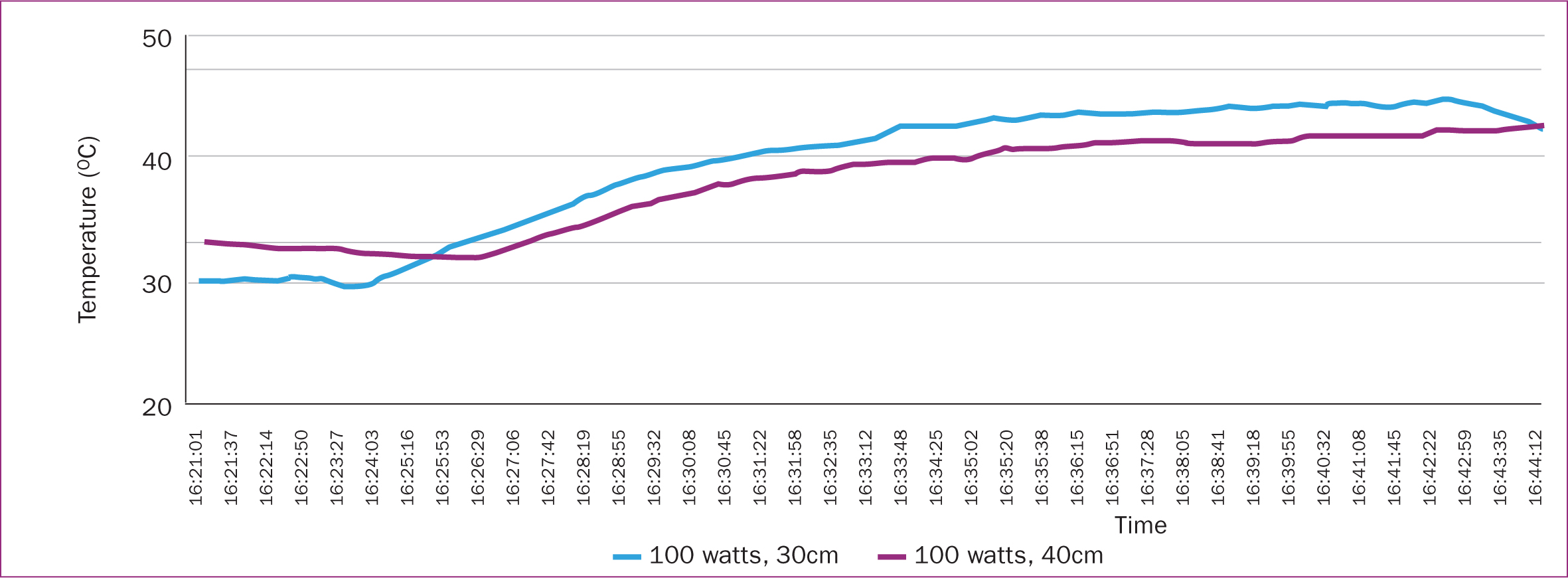

In the second trial, solid objects were heated by photobiomodulation near infrared with a power of 100 watts. The temperatures at distances of 30 cm and 40 cm were compared. The results of the 16-minute test showed that at a distance of 30 cm, the temperature of the solid object reached more than 50°C, while a distance of 40 cm produced a maximum temperature of 40°C (Figure 3).

Based on the results of the second trial in the laboratory, the tool's work procedures were obtained. The participant was lying on their side, then heat was directed to their abdomen (uterus). The intervention dose used a near infrared lamp at 100 watts, 40 cm from the mother's stomach for 15 minutes.

A pre-exper imental study to implement photobiomodulation near infrared on 80 adult women was carried out. The average age of respondents was 32.05 years, the average body weight was 59.74 kg, the average height was 156.29 cm, the average abdominal circumference of respondents was 83.80 cm, and the average body mass index was 24.171. The paired t-test and Wilcoxon test analysis showed that there was a significant difference between the pre-test and the post-test datapoints for temperature and comfort (P<0.001 in both tests) (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of temperature and comfort level before and after photobiomodulation trial (n=80)

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Pre-test | 36.144 | 0.646 | 0.001 (paired t-test) |

| Post-test | 36.488 | 0.547 | ||

| Comfort | Pre-test | 2.96 | 0.191 | 0.001 (Wilcoxon signed ranks test) |

| Post-test | 3.40 | 0.493 | ||

Third stage

In the last stage, a quasi-experimental study was carried out with 90 postpartum women who were divided into three groups, the photobiomodulation near infrared intervention group, the traditional group and the routine interventions group. The demographic variables showed that parity, religion, education and age were homogenous (P>0.05), although tribe was not. The mean and standard deviation of age in the intervention, traditional and routine groups were 27.90±4.037, 28.37±4.810, 29.17±4.044, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Respondents' demographics (n=90)

| Variable | Photobiomodulation, n=30 (%) | Traditional, n=30 (%) | Routine, n=30 (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | 2 | 21 (70.0) | 22 (73.4) | 16 (53.3) | 0.128 |

| 3 | 8 (26.7) | 7 (23.3) | 10 (33.4) | ||

| 4 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (13.3) | ||

| Religion | Muslim | 25 (83.3) | 24 (80.0) | 24 (80.0) | 0.932 |

| Christian | 5 (16.7) | 6 (20.0) | 6 (20.0) | ||

| Tribe | Batak | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0.000 |

| Bengkulu | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| Jawa | 13 (43.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (16.7) | ||

| Padang | 4 (13.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| Palembang | 13 (43.3) | 30 (100.0) | 21 (70.0) | ||

| Education | Primary | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 5 (16.7) | 0.292 |

| Secondary | 28 (93.4) | 24 (80.0) | 21 (70.0) | ||

| Graduate | 1 (3.3) | 5 (16.7) | 4 (13.3) | ||

| Age, mean±standard deviation (years) | 27.90±4.037 | 28.37±4.810 | 29.17±4.044 | 0.518 | |

A number of variables were measured in the three groups and compared for differences on days 1, 3, 6 and 10 (Table 3). Systolic pressure showed a significant difference on days 3 and 6. Diastolic pressure only showed changes on the first day and not on the following days. Pulse, respiratory temperature and fundal height showed changes from day 1 to day 10. There were no significant changes in afterpain, breast milk, REEDA or comfort on the first day. However, on days 3, 6 and 10, there were significant changes. For the psychosocial variables, changes were apparent from days 6 and 10 onwards.

Table 3. Comparison of postpartum physical and psychosocial adaptation (n=90)

| Variable | Day | Photobiomodulation | Traditional | Routine | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean sistole ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 115.33±6.29 | 116.00±5.63 | 112.67±5.83 | 0.076 |

| Day 3 | 113.00±5.35 | 116.33±5.56 | 111.67±6.48 | 0.014 | |

| Day 6 | 114.33±5.04 | 116.67±6.07 | 112.00±6.64 | 0.031 | |

| Day 10 | 114.00±5.63 | 111.47±21.07 | 113.67±6.15 | 0.761 | |

| Mean diastole ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 76.33±4.90 | 74.67±5.71 | 72.67±4.50 | 0.020 |

| Day 3 | 73.67±5.56 | 75.33±5.07 | 72.00±6.10 | 0.100 | |

| Day 6 | 74.67±5.71 | 73.67±4.90 | 73.33±6.61 | 0.655 | |

| Day 10 | 76.00±5.63 | 74.67±5.07 | 73.33±6.61 | 0.231 | |

| Mean pulse ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 79.80±3.03 | 78.67±3.34 | 80.73±2.59 | 0.046 |

| Day 3 | 77.97±3.31 | 77.57±3.66 | 81.27±3.04 | 0.000 | |

| Day 6 | 77.67±2.88 | 78.47±3.71 | 81.13±3.67 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 78.40±3.20 | 78.13±3.47 | 81.37±3.77 | 0.002 | |

| Mean respiratory ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 22.30±1.54 | 23.07±1.11 | 20.83±2.07 | 0.000 |

| Day 3 | 22.33±1.27 | 22.83±1.66 | 21.13±2.27 | 0.005 | |

| Day 6 | 22.37±1.27 | 22.43±1.72 | 20.60±2.11 | 0.001 | |

| Day 10 | 22.50±1.48 | 22.87±1.68 | 21.13±2.29 | 0.005 | |

| Mean temperature ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 36.42±0.37 | 36.52±0.32 | 36.70±0.37 | 0.014 |

| Day 3 | 36.58±0.43 | 36.43±0.38 | 36.72±0.21 | 0.014 | |

| Day 6 | 36.46±0.31 | 36.44±0.32 | 36.72±0.19 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 36.44±0.36 | 36.41±0.34 | 36.68±0.27 | 0.002 | |

| Mean fundal high ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 11.17±0.53 | 10.60±0.68 | 10.80±0.61 | 0.003 |

| Day 3 | 7.57±0.77 | 8.73±0.83 | 10.13±0.68 | 0.000 | |

| Day 6 | 4.83±0.87 | 6.23±0.97 | 9.23±0.63 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 1.87±1.17 | 3.50±1.38 | 4.67±1.03 | 0.000 | |

| Mean afterpain ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 7.53±1.07 | 7.93±1.02 | 7.77±0.94 | 0.321 |

| Day 3 | 4.37±1.19 | 6.97±0.85 | 7.07±0.74 | 0.000 | |

| Day 6 | 3.00±0.79 | 6.07±0.83 | 6.07±0.83 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 1.83±0.12 | 3.67±1.24 | 4.87±1.22 | 0.000 | |

| Mean breastmilk ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 13.87±5.06 | 6.90±3.89 | 6.10±3.54 | 0.076 |

| Day 3 | 31.00±7.59 | 21.50±6.59 | 17.17±5.20 | 0.000 | |

| Day 6 | 53.50±9.67 | 37.17±5.52 | 27.83±6.91 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 73.50±10.60 | 58.17±11.18 | 42.33±13.18 | 0.000 | |

| Mean REEDA ± standard deviation | Day 1 | 5.60±1.22 | 6.00±1.55 | 6.10±1.30 | 0.526 |

| Day 3 | 4.93±1.29 | 3.93±1.14 | 5.27±1.31 | 0.000 | |

| Day 6 | 3.40±0.97 | 3.37±1.13 | 4.57±1.25 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 1.53±1.01 | 2.33±1.09 | 3.30±1.26 | 0.000 | |

| Mean comfort | Day 1 | 25.40±4.15 | 26.47±5.02 | 25.80±4.36 | 0.901 |

| Day 3 | 21.67±4.34 | 25.53±5.10 | 25.57±4.26 | 0.001 | |

| Day 6 | 18.63±4.47 | 24.60±5.25 | 25.40±4.48 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 16.23±4.58 | 23.73±5.63 | 25.17±5.23 | 0.000 | |

| Mean psychosocial | Day 1 | 50.90±5.73 | 48.00±6.67 | 48.40±4.67 | 0.133 |

| Day 3 | 48.33±5.96 | 47.33±6.64 | 48.17±4.96 | 0.781 | |

| Day 6 | 41.37±6.27 | 46.50±6.46 | 47.97±5.46 | 0.000 | |

| Day 10 | 35.77±9.04 | 44.73±7.34 | 47.33±6.63 | 0.000 |

Discussion

Physical and psychosocial adaptation concerns in postpartum women can lead to complications. This study used a research and development approach carried out in three stages. A tool was developed called photobiomodulation near infrared with a local cultural approach based on the needs of postpartum women.

Qualitative research to explore the needs of postpartum women was conducted in order to cope with physical and psychosocial problems. Tools and tests related to their effectiveness for physical and psychosocial changes were carried out.

Need to develop therapeutic tools

Using a qualitative approach in the first stage of the study, three themes emerged: physical and psychosocial changes during the postpartum period, traditional treatments and the modification of therapeutic tools. Postpartum women experienced both physical and psychological changes. To cope with this, they underwent traditional treatments, such as bathing with spices, massage and sitting on heated bricks. There is still a gap regarding the effectiveness of these treatments and their possible harmful impacts on health. However, based on the interviews, participants hoped that therapeutic tools would be developed that were easier to use and beneficial for postpartum women.

Traditional treatments for postpartum women, which provide benefits and are easy to use, are more accepted by the community than medical treatments. This is likely because these interventions have been carried out for a long time and are hereditary. Previous studies state that warming the postpartum body as a form of traditional postnatal care has many physical benefits for the mother (Bazzano et al, 2020). However, some traditional treatments may potentially be harmful (sitting on heated bricks) and need more investigation if they do not follow the medical standard (Raven et al, 2007). The authors recommend that innovation regarding traditional treatments that follow medical standards would be useful.

Photobiomodulation near infrared tool development

The development of the photobiomodulation near infrared tools to be applied in communities requires a good approach because of the cultural differences in treatments that are carried out. Based on the first stage, Photobiomodulation near infrared was initiated based on postpartum women's needs and suggestions from massage shamans and traditional figures. The tools can be categorised as innovative tools using infrared. Previous studies show that infrared therapy has many benefits for wound healing and relaxation (Tsai and Hamblin, 2017; Gravity Float, 2021). Photobiomodulation near infrared can be a suitable tool for coping with physical and psychological concerns among postpartum women.

Effectiveness of photobiomodulation near infrared on physical and psychosocial adaptation

In the present study, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures did not show any significant changes between groups, meaning the vasodilation response of blood vessels did not show a significant change compared to traditional interventions (Kominami et al, 2020). However, photobiomodulation near infrared produces an increase in systolic–diastolic pressures together, according to research by Isley and Katz (2019). Vital sign responses are influenced by factors such as body mass index (Prasetyo et al, 2019) and waist size (Dewi et al, 2019). A decrease in blood pressure is the result of dilatation that occurs following photobiomodulation near infrared through the release of nitric oxide (Buzinari et al, 2019) in the brachial artery (Kominami et al, 2020), as well as increased blood capillary dilatation (Grzybowski, 2016).

The photobiomodulation near infrared intervention resulted in significant differences in pulse, respiration and body temperature. Other studies have also found that 660 nm photobiomodulation near infrared rays with an energy of 28.2 J cause a decrease in pulse (Moraes et al, 2019), plasma volume (Drzazga et al, 2020) and respiratory problems (Samuel et al, 2020). Photobiomodulation near infrared provides a thermographic effect that has been found to increase body temperature in pregnant women (Kominami et al, 2020).

Uterine fundal height decreased in all groups. However, the photobiomodulation group showed a faster significant decline. Photobiomodulation near infrared stimulates muscles to contract (Toma et al, 2018; Kobayashi et al, 2019), and the feeling of warmth provides comfort and pain relief (Dib et al, 2020). In addition, the hormone oxytocin can be stimulated and accelerate the process of uterine involution (Morberg et al, 2019). The respondents in the present study felt a decrease in afterpain after receiving regular photobiomodulation near infrared. This is in accordance with previous research (Masuda et al, 2005; Lai et al, 2017).

The photobiomodulation intervention provided a warm sensation, which increases the permeability of blood vessels. This can improve the quality of sleep, allowing for adequate rest and increasing the secretion of the hormones prolactin and oxytocin, which can increase milk production (Sihotang et al, 2020). Photobiomodulation near infrared can also prevent mastitis caused by an infection (Lage et al, 2014). The concerns that many postpartum mothers can experience include pain and lengthy wound healing. Radiation therapy such as photobiomodulation near infrared has been shown to speed up the wound healing process (Lee et al, 2020).

Given regularly, photobiomodulation near infrared can provide comfort to postpartum mothers. It can increase regulation of fluids through sweating, which can release toxins (Tuk et al, 2017), improving sleep quality. This can stimulate endorphins, increasing comfort. The increase in mood can reduce the chance of psychological and psychosocial disorders in postpartum mothers.

Limitations

Photobiomodulation near infrared tools can be a promising complementary therapy in coping with physical and psychological concerns among postpartum women. However, the development of these tools needs to be improved in the future, so they can be provided as a wireless product that can be used digitally and be controlled by mobile applications on smartphones.

Conclusions

Regular nursing interventions with photobiomodulation near infrared carried out in the postpartum period are effective in accelerating the physical and psychosocial recovery of postpartum women. There were differences in physical adaptations (pulse, respiration, temperature, fundal height, afterpain, REEDA signs, amount of breast milk and comfort) and psychosocial adaptations of postpartum mothers in the intervention group, equal to those provided by traditional care and routine care, according to four measurement tools. Photobiomodulation near infrared may be a new tool to accelerate healing among postpartum women. The authors recommend that health providers use this device as an alternative intervention in postpartum care. Maternity nurses especially are encouraged to use photobiomodulation near infrared as a new approach that can be implemented in nursing care. Future studies may develop an improved digital indicator and implement this as a complementary therapy for wound healing.

Key points

- Innovation-based cultural nursing interventions are needed for postpartum women.

- Ease of use, accessibility and safety are the main concerns with modern devices among postpartum women, traditional carers and massage shamans in Indonesia.

- A photobiomodulation near infrared tool was developed to warm a mother's abdomen as part of postpartum care.

- The intervention effectively improved the physical and psychosocial adaptation of postpartum mothers.

CPD reflective questions

- Do you think intervention-based culture, especially in treatment of postpartum women, will be degraded by the development of technology?

- If technology like that described in this article were developed, designed to treat postpartum women, would you like to implement it for your patients?

- How would you respond if a patient chose to reject the use of a technology-based treatment?