The risk factors, health implications and socio-economic repercussions of adolescent pregnancy and early childbearing is widely covered in literature. The World Health Organization ([WHO], 2018a) and the United Nations Population Fund (2017) coordinate through various ongoing campaigns to address this phenomenon that is regarded as a global issue, accounting for 11% of births worldwide (Koffman, 2012; Ganchimeg et al, 2014; Torres et al, 2015; Cook and Cameron, 2017). In South Africa, in 2018, 107 548 adolescent girls between 15–19 years of age, and 3 235 adolescent girls between 10–14 years of age registered births—together representing 11% of all 1 009 065 registered births in the country during that year (Statistics South Africa, 2019).

The dynamics surrounding adolescent childbearing are different from adults due to various factors and play a major role in their experiences of childbirth. These factors include their social contexts as adolescents, ongoing physical and psychosocial development, financial dependency and often a lack of educational fundamentals (Low et al, 2003; Montgomery, 2003; Zasloff et al, 2007; Sauls and Grassley, 2011; Ganchimeg et al, 2014; Cook and Cameron, 2017).

Even though the adult woman's experience of childbirth is well-documented, the research available lacks adequate information about childbirth from the perspective of the adolescent (Goodman et al, 2004; Zasloff et al, 2007; Cipolletta and Balasso, 2011; Michels et al, 2013; Aparicio et al, 2019). For the purpose of this research, middle adolescence is regarded as 14–16 years of age based on Erikson's Theoretical Model of Human Development (Erikson, 1968; Sadock and Sadock, 2007).

Sauls' (2011) research on the intrapartum care and needs of adolescents and Michels et al (2013), who focused on women of all ages, both showed that the childbirth experience, whether positive or negative, can have an impact on the psychological outcomes for the mother and baby. This study focused on this pivotal event in a South African context in order to contribute to the body of knowledge and enable adolescent mothers' voices to be heard.

Research problem

From personal experience and observation, it appeared as if adolescents were more unprepared and required extensive emotional support and encouragement during childbirth from the midwives than the mothers who were older did.

Research objective

The aim of the study was to explore the lived childbirth experiences of mothers of middle adolescent age who were living in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

Research question

How do middle adolescent mothers in the Western Cape experience childbirth?

Methods

Study design

Our study was guided by a qualitative design and phenomenological approach as described by Edmund Husserl. This approach required setting aside personal thoughts and ideas about the phenomenon being studied and to learn as much as possible about the phenomenon during fieldwork and information unravelling (McConnell-Henry et al, 2009). As described by van Manen (1990), the language of phenomenology is unique and often deviates from the standard terminology used in research. van Manen refers to conversations, information gathering and unravelling to describe the methodology of phenomenology.

Setting

The participants were invited over a period of seven months during 2015 from the postnatal wards of two public sector referral hospitals in the Western Cape province.

Participants

A purposive sampling method was appropriate for a qualitative design and therefore applied in this research. Eligibility of the participants was determined according to the following inclusion criteria i) adolescents aged 14–16 years at the time they gave birth ii) English- or Afrikaans-speaking participants, as these are the two locally spoken languages in which the primary researcher is fluent iii) adolescents who had a normal vaginal (vertex) birth that resulted in a live infant iv) barring age as a risk factor, a low-risk pregnancy at 37 completed weeks of gestation or more, with one or more antenatal visits and v) Gravida 1 Para 1 (G1P1) postpartum. Any potential participants who suffered maternal or neonatal complications during birth were excluded from this study.

In total, 13 adolescents were approached and invited, six participated in this study, and the rest either did not return for conversations or withdrew from the study. Hale and Kitas (2008) maintained ‘that true data saturation can never really be achieved’ and that the aim of phenomenology is to gather ‘full and rich personal accounts from the sample used’. No new information emerged after five conversations and therefore six conversations were deemed sufficient, offerring rich information into the phenomenon.

Collection of information

Initially, the timeline for information gathering to take place was within two weeks postpartum. However, this had to be adjusted during field research as no participants returned for the conversations. Conversations were then held with participants before discharge and within 72 hours after they had given birth as this is a standard period of hospitalisation post-birth.

The primary researcher visited the wards daily with permission from the relevant hospital and ward staff, and approached eligible participants and their parents/legal guardians post-birth to inform them about the study, provide information leaflets and invite them to participate. Consent from parents or legal guardians and assent from adolescents were required to be signed prior to any formal recording which was then only done with the adolescents. Adolescents had time until they were discharged to consider participation and to complete the conversations. They could withdraw at any point should they not feel ready for the conversation.

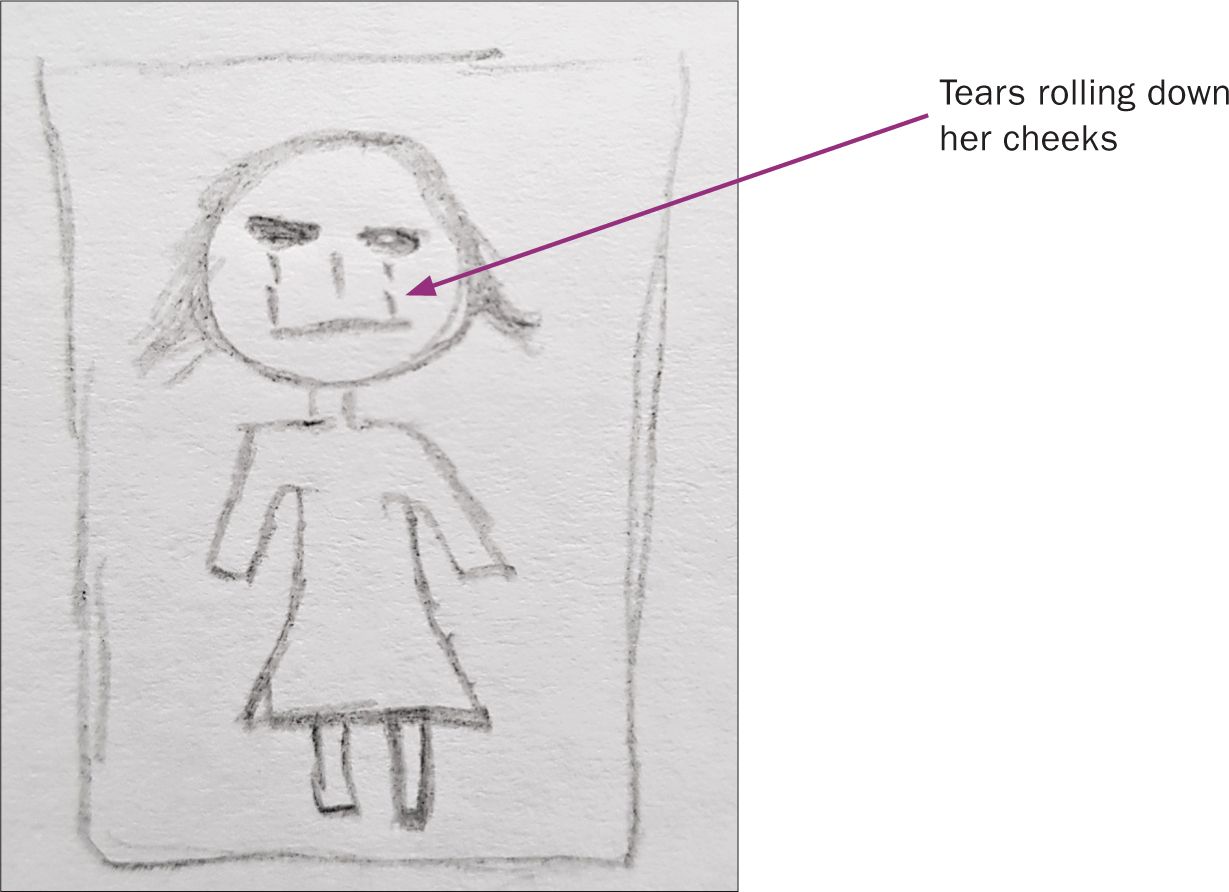

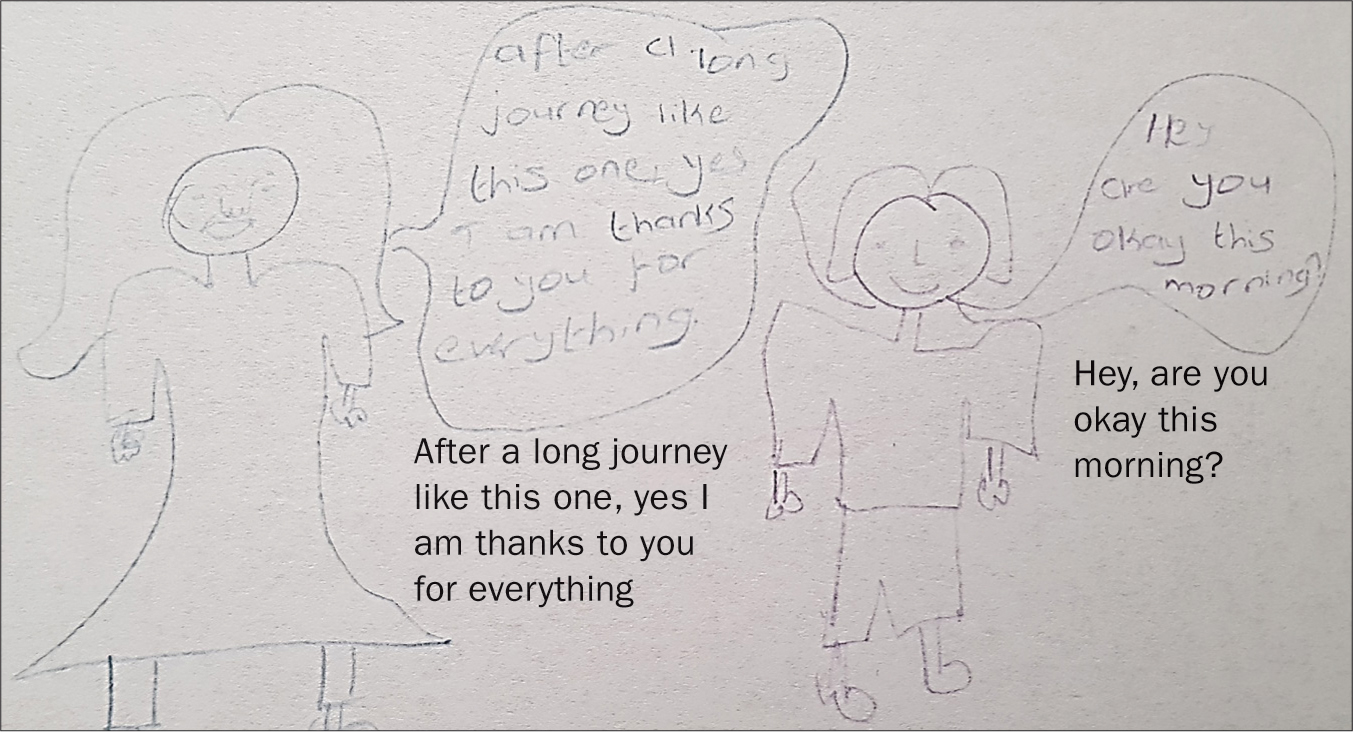

A reflective drawing was used by asking, ‘please draw what happened in the labour room when you gave birth’. Drawings can bring to light additional information that might not be verbalised and reflect a person's state of mind, even though a participant may be unable to translate this into words. In addition, a drawing can offer a person a non-verbal chance to express feelings or thoughts that they may not have been aware of before (Oster and Crone, 2004). For this reason, drawings were not analysed but solely employed as conversation starters and to provide focus and prompts during discussions on the phenomenon. The conversation was initiated after the drawing had been completed by asking the participant: ‘please tell me about your drawing’. These in-depth conversations usually lasted between 15–25 minutes and were led by the responses obtained. Audio recordings were used and transcribed verbatim by the primary researcher and field notes were also used to gather and verify information.

Follow-up conversations were scheduled with participants. However, after the initial conversations, only three participants returned. During this follow-up conversation, the clusters of themes derived from their experiences were presented and explained. They had an opportunity to add information and/or to clarify any misinterpretations. No new information emerged during these conversations and the information obtained from the initial conversations was subsequently used for development of the themes.

Information unravelling

Three key concepts described by Husserl's philosophy of phenomenology were used as guidelines for the development of the themes—see Table 1 for an extract of the unravelling process. Husserl's thinking, amongst others, three concepts that relate to the essence of a lived experience that were applied during the unravelling include i) the essences of the adolescent mothers' experiences of childbirth ii) their intentionality and consciousness (state of mind) during childbirth and iii) their life-world experiences during childbirth (Jennings 1986; Siewert 2006; Smith 2013). The seven steps of information unravelling as described by Colaizzi (1978) were followed.

| Meaning | Stacey | Unathi | Cindy | Mavis | Aquila | Farrah | Cluster/category | Sub-theme | Essential theme and Husserlian meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe pain | How is she going to take the baby out and why is the pain so sore and then she just looked at me and she walked away | I never thought that … bringing someone to earth would be so hard and … it's just stressful | It was very difficult because the pains were so sore … you hurt a lot | It was very sore, I couldn't take it anymore | It's hard for me. For teenagers like me. So hard. And … painful. Yhew … it's not nice to be there. Maybe it's my age, I'm young | I felt like I was going to die! That's all you feel, like you're going to die, you're not going to make it, you just telling yourself ‘I'm not going to make it, I'm not going to make it, I know I'm not going to make it’ | Pain | Pain | Overwhelming experience (life-world) |

| Birth companion | My mommy. She was the only one that could make it easy … for me | I think … having my mom there with me I think … [Why] It would mean everything | Because my mom will help me calm down | And she [mother] told me sweet words and they just made me feel better | And what was good for me was that my mom was there with me | She'll guide me in the right direction, she'll tell me, ‘Don't do that’ … uhm … ‘Do this way’ … uhm … that's how it help me | A need/want | Mother as birth support for all | Distress and unsettled without the support (state of mind) |

Ethical considerations

This research protocol was submitted to the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Cape Town and received ethical approval to conduct the study (HREC 256/2014). The Provincial Government of Health granted permission to conduct the research in the province and permission was obtained at the individual hospitals as well.

Owing to the participants being minors (not yet 18 years old) the parents or legal guardians' consent was needed, as well as assent from the adolescents to participate in the study according to the Children's Act, No 38 of 2005 (Children's Act, 2005; 2006). When conducting research involving minors, it is imperative that there is minimal risk as they are classified as vulnerable participants. Parental or legal guardian's consent for the conversations was obtained prior to obtaining assent from the adolescent. The researcher recognised the possibility of causing emotional or psychological distress (World Medical Association, 2013) and provided the opportunity for debriefing sessions afterwards and contact details for local young mothers support groups.

All participation was voluntary and pseudonyms were chosen by the participants to ensure confidentiality (Brink et al, 2012).

Findings

The participant profile is presented in this section, followed by a detailed explanation of the essential themes and sub-themes identified in this study. Six adolescents participated in the study by which time there was no new information gathered from the follow-up conversations. Table 2 provides a description of the participants.

| Participant | Age | Ethnicity* |

|---|---|---|

| Farrah | 14 years | Coloured |

| Stacey | 15 years | Coloured |

| Mavis | 15 years | Coloured |

| Cindy | 15 years | Coloured |

| Unathi | 16 years | Black |

| Aquila | 16 years | Black |

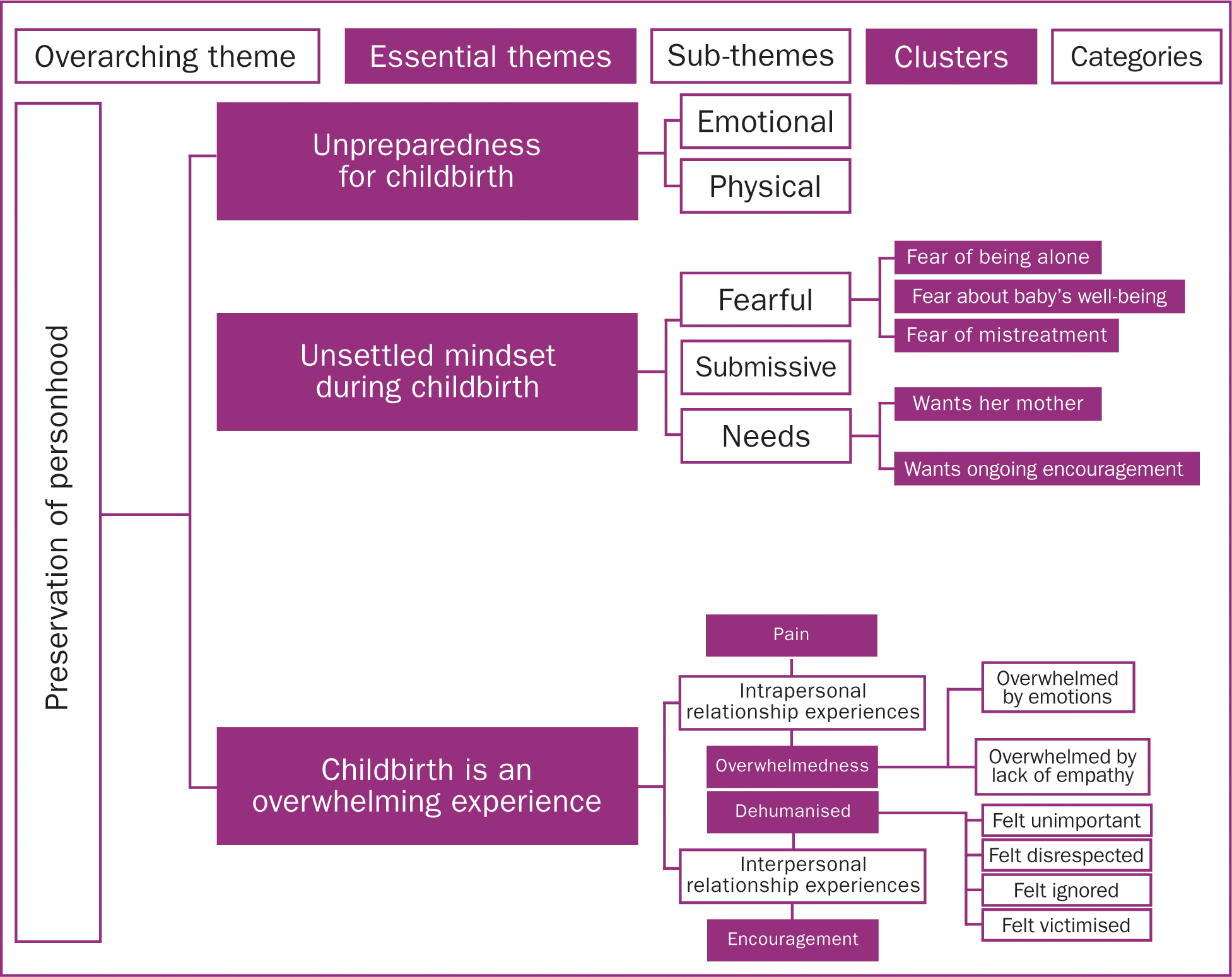

Overarching theme: preservation of personhood

Although the participants were divided about positive or negative birth experiences, the main focus on their entire childbirth experience was that of the battle to preserve their personhood. Their narratives describe their efforts to preserve their sense-of-self and to not lose their individuality and humanity through their experience of childbirth. Farrah explained how an assault on her personhood had left her feeling like someone unworthy or valued as a person:

‘Well, it made me feel like somebody that's useless because of the way she treated me and … it was like “ruk en pluk” [push and shove].’

When the midwife treated her in a friendly manner and asked how she was feeling after the birth:

‘Like … I felt like a person again.’

The most important aspects of childbirth were to be treated as a human being and to feel worthy of respect and care. Three essential themes were identified during the unravelling process i) the essences of the childbirth experience were unpreparedness for childbirth ii) an unsettled mindset during childbirth (intentionality and consciousness), resulting in fear and anxiety and iii) the life-worlds of the participants was that childbirth is an overwhelming experience. The three essential themes emerged from the sub-themes and were further divided as illustrated and explained in Figure 1.

Unpreparedness for childbirth

The adolescents in this study demonstrated poor preparation and a lack of antenatal information about labour and childbirth.

Emotional

Their ignorance was obvious in their accounts of confusion and uncertainty about the process happening in their bodies. The labour and birth were nothing like they had imagined:

‘I never thought that … bringing someone to earth would be so hard and … it's just stressful. And then after that I realised; this … is really a hard thing.’

Physical

Many of the participants referred to their age and immature physical developmental stage as reasons for finding labour so difficult. Their narratives illustrated that the participants were aware of the fact that they were not fully developed physically when they fell pregnant:

‘It is not nice because your-your body isn't yet fully developed like an adult's. And it's sore too.’

Unsettled mindset during childbirth

The participants' state of mind during childbirth was that of feeling unsettled and a heightened sense of fear.

Fearful

It was an unfamiliar environment with unfamiliar faces and an unknown journey from which there was no turning back. They needed companionship and were afraid to be alone:

‘Your mother and your daddy … or your boyfriend … and so must be there then you'll feel all right ’cause if you you're going to feel alone and you are alone then you're going to feel lonely. [Pause] And … you're going to think nobody's supporting you.’

The participants felt fearful about their babies' well-being when they gave birth:

‘I felt scared … worried if the baby's going to be healthy if he was delivered.’

Stemming from different experiences, either antenatally or at different hospitals, the participants expressed a fear that they would be mistreated by the nursing staff:

‘And even when … if I'm giving birth, I thought they're going to be shouting and stuff.’

‘Uh … okay, I think I cried also because of how the nurses there under by the MOU treated me.’

An MOU is a midwife obstetric unit, a local primary level midwifery clinic in South Africa where women with low-risk pregnancies receive antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care.

Submissive

The participants demonstrated submissive behaviour towards the midwives. All the participants felt that if one followed the midwives' instructions and did as they were told, the birth would be safe and the baby would be unscathed.

‘Because if you don't do what they tell you to do then you can stay there forever and you can't give birth and the baby can't come out … you just need to follow their instructions.’

Needs

Despite some of the participants still being in relationships with the fathers of their babies, the fathers did not feature as important factors during childbirth. It was important to all the participants to have their mothers with them.

[What had helped her cope with labour and birth] ‘My mommy. She was the only one that could make it easy … for me.’

Besides wanting their mothers with them as support persons, they expressed the need to be reassured during labour that they are doing well and to be encouraged to keep going.

‘No … but she [the midwife] tried. She could say I must … I must be strong. That's what she could say … I must just be strong [speaks loudly].’

Childbirth is an overwhelming experience

The participants' ‘overwhelmedness’ emanated from their own physical experiences as well as their interaction with the healthcare professionals. Therefore, the sub-themes identified were grouped into the participants' intra- and interpersonal experiences.

Intrapersonal experiences

Intrapersonal is defined as ‘relating to or within a person's mind’ (Cambridge University Press, 2019c). Intrapersonal experiences were characterised by being overwhelmed by pain and overwhelmed by emotions.

| Emotions | Quotes from the participants |

|---|---|

| Frustration | ‘…’Cause I was frustrated with the people. I got frustrated ’cause they didn't know what to do; they were just standing there every time in front of me.’ —Stacey |

| Embarrassment | [How she felt in the postnatal ward where she shared a room with other mothers] ‘I was a bit shy because I am very young.’ —Cindy |

| Irritation | [Coping with contractions during labour] ‘… At that moment, everything irritates you.’ —Farrah |

| Scared | ‘I felt scared … worried if the baby's going to be healthy if he was delivered.’ —Stacey |

| Anger | ‘They didn't help me! [almost shouting]. My mother helped me [during labour]. —Mavis |

| Sadness | ‘Ah … I felt sad because [laughs] … that person, she – they were − they already have children and she knows how painful it is but she … still, she doesn't feel that, she didn't feel shame for me.’ —Aquila |

| Relief | ‘I felt relieved. Yeah … Actually no one was shouting at me.’ —Unathi |

| Excitement | [After the baby was born] ‘I was … excited.’ —Unathi |

Interpersonal experiences

Interpersonal refers to the concept of ‘connected with relationships between people’ (Cambridge University Press, 2019b). Interpersonal experiences were characterised negatively by feeling dehumanised by the interactions or positively by being encouraged.

[How it made her feel]: ‘They respect … they respect me.’

| Emotions | Quotes from the participants |

|---|---|

| Felt unimportant | ‘Yhew, I feel … I just feel useless. Why is she going to shout at me? … Everyone's going to turn and look at me and then, all those words are going to hurt me.’ —Unathi |

| Felt disrespected | ‘Even though some of them was so rude but … some of them tried. I can say that.’ [When asked how it made her feel] ‘… It upset me and it makes me sad.’ —Aquila |

| Felt ignored | ‘It was almost like they [the nurses] didn't have time for me. But they were doing nothing, just walking down the aisles.’ —Stacey |

| Felt victimised | ‘Well, I felt bad because why isn't she doing it to the other patients? Why to me only?’ —Farrah |

Unathi was the only participant who reported a positive childbirth experience; Figure 3 illustrates her birth experience.

‘She was like, “just relax” and I was like, “wow”, I've never had someone saying that to me, to relax and then, maybe just do it. And then I did it.’

And her interpretation and experience of the midwife's words:

‘Yeah, that she actually cared about people.’

Discussion

Despite healthy outcomes for all of the participants and their babies, their narratives were riddled with pent-up emotions of sadness, anger, relief, confusion and worthlessness. This section discusses the findings according to the Husserlian concepts and reviews what is known in existing literature.

Respectful care during childbirth

The first essential theme or essence of adolescents' childbirth experiences was unpreparedness characterised by feelings of inadequate physical development and a lack of emotional preparedness for the birth. The second essential theme (intentionality and consciousness) during childbirth was an unsettled state of mind. The participants experienced a heightened sense of fear and a submissive approach was used as a coping mechanism. The third essential theme or participants' life-world during childbirth was identified as an overwhelming experience divided into intra- and interpersonal experiences.

There is currently a dearth in the literature on adolescent childbirth since most studies focus on either adolescent pregnancy or parenthood. Similarities from existing research on adolescent childbirth included i) respectful nursing care ii) a high demand for pain relief, and iii) the need for a birth companion (Montgomery, 2003; Sauls, 2004; 2010). Midwives caring for adolescents in labour are often seen ‘as the deciding factor in whether their experiences of childbearing are positive or negative’ (Sauls and Grassley, 2011) and they can play a significant role in promoting healthy outcomes for both the mother and baby (Low et al, 2003; Sauls, 2010).

The findings of this study concur with the literature reviewed as the participants experiences were influenced to a large extent by the type of care they received from their midwives and other healthcare professionals. Rijinders (2008), Elmir et al (2010) and Chadwick et al (2014) found that women who had negative relationships with their caregivers – lacking adequate support, pain relief, information or respectful care – reported negative childbirth experiences. Sapountzi-Krepia et al (2011) reported that positive experiences of childbirth were all based on positive relationships with caregivers where guidance and labour support were mentioned as important aspects of the patient-midwife relationship. Caring for a woman's basic needs during childbirth, her emotional well-being and respecting her individuality, all form part of a ‘holistic’ and respectful approach to caring, irrespective of age when entering motherhood.

The findings showed that pain relief was reported as a top priority during childbirth. This was consistent with Sauls (2010) who found that adolescents reported pain relief to be the most effective support measure that nurses could offer them during labour. The participants expressed the need to cope with their fear of being alone by wanting their mothers as birth companions. This correlates with Anderson and Gill (2014) who measured, among other factors, the effects of fear during birth on adolescents. They found that a birth companion – the mother or a female relative who were regarded as an important supportive measure during childbirth (Khresheh, 2010; Anderson and Gill, 2014) – had the biggest influence on younger adolescents' birth experiences and reduced their levels of fear. From the conversations, it appeared as if mistreatment by the nursing staff was experienced more often by the participants who were alone (in South Africa, patients in public sector maternity wards are cared for by doctors and a nursing team consisting of midwives, nursing assistants and nursing students). Reports of victimisation from several participants in this study was a concern. Arthur et al (2007) and Bailey et al (2004) found similar trends in their research where adolescents and their partners reported being treated badly or ‘differently’ to mothers that were older; however, the literature is limited.

Studies on abuse or ‘obstetric violence’ in maternity health facilities, some dating back 20 years, found that some groups of people may be singled out and receive ‘punishment’ for not adhering to society's moral codes, such as adolescents who are pregnant (Jewkes et al, 1998; D'Oliveira et al, 2002; Jewkes and Penn-Kekana, 2015; WHO, 2020).

It is noteworthy that not all the participants regarded mistreatment as negative. Some felt compelled to keep quiet and viewed the treatment as harsh but necessary for their and their babies' safety. Whether the treatment they received, and their interpretations thereof, were associated with individual personality traits, culture, ethnicity or local context is unclear from this study as only certain groups of the local population were represented. Research into obstetric violence is ongoing (Chadwick et al, 2014; Jewkes and Penn-Kekana, 2015; WHO, 2020) and exploration of contributing factors to mistreatment and women's perspectives thereof can provide better clarity in future.

A unique sub-theme identified during the information unravelling was that the participants relinquished their control to the midwives' authority based on the belief that this was the only way in which they could safely give birth. This corresponded with Drake's (1996) theory on the developmental tasks of adolescents that middle adolescents tend to follow higher authorities' suggestions in order to maintain good relationships. Regardless, adolescents should be encouraged to preserve their autonomy during childbirth and to have a voice of their own.

Training in adolescent-oriented (and all other) maternity healthcare is absolutely vital to support mothers on their new journey and provide care that is tailor-made to their needs (Renfrew et al, 2014). An existing initiative includes the role of an adolescent specialist midwife that provides age-appropriate care and support (Leicester Maternity Services, 2012; Best Beginnings, 2020; Local Government Association, 2020; Leeds Teaching Hospital, 2020). In the local context, this could prove effective to encourage pregnant adolescents to seek healthcare in time and receive the relevant antenatal education and age-appropriate intrapartum support that could positively impact their birth experiences.

Limitations of the study

The findings of this study cannot be generalised to other middle adolescents and their childbirth experiences due to the local South African context, demographics and socio-economic circumstances that are all factors that could have influenced the participants' experiences. However, the research process and methodology adopted in this study was stipulated and may be useful for other researchers.

The adjusted timing of the conversations within 72 hours post-birth proved to be optimal in gathering the true and raw lived experiences of the participants prior to breastfeeding and before other postnatal factors clouded their memories. The researchers recognised that sharing of their experiences could incite unpleasant memories. The primary researcher was adequately skilled to guide conversations and to create rapport and a safe space to support and/or refer participants appropriately when required.

We recognised that language restrictions limited participation but this avoided having to use a translator and therefore reduced the possibility of misunderstanding or misinterpreting the findings.

Recommendations

In line with the WHO recommendation for intrapartum care and obstetric violence to ensure positive childbirth experiences (WHO, 2018b; 2020), we recommend:

Conclusion

Adolescents are transitioning from childhood into motherhood when they are admitted to maternal healthcare facilities. The onus is on all healthcare professionals to ensure that these young mothers return home feeling valued as human beings, worthy of care and respect, confident as new mothers and empowered as women that will ensure the well-being of their children.