Human milk is acknowledged to be the optimum source of nutrition for infants, while also being beneficial to maternal health (Victora et al, 2016). As such, the World Health Organization ([WHO], 2019) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of an infant's life, followed by breastfeeding and appropriate complementary foods up to two years of age or beyond. Despite this, breastfeeding rates in the UK remain some of the lowest in the world; the last UK-wide infant feeding survey reporting that while 81% of mothers initiated breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding rates declined to less than 25% by six weeks (IFF Research, 2013).

The reasons for premature discontinuation of breastfeeding are complex and varied at what is a highly emotive time in a new mother's life. These issues may be social, psychological or physical (IFF Research, 2013; Odom et al, 2013). Much of the research into physical problems experienced by breastfeeding mothers focuses on issues relating to breastfeeding itself, such as latch difficulties, nipple pain and perceived milk insufficiencies (Binns and Scott, 2002; Mohammadzadeh et al, 2005; Kent et al, 2015). However, in understanding breastfeeding difficulties, other factors may also affect a mother's ability to establish a sustainable breastfeeding relationship with her infant.

Some of these factors are well-studied, such as the effect of analgesia and anaesthesia during labour (Rajan, 1994; Brown and Jordan, 2014), early separation of mother and infant (Nyqvist and Ewald, 1997; Rapely, 2002) and the impact of skin-to-skin contact (Bramson et al, 2010; Lau et al, 2017; Mekonnen et al, 2019). However, the effect of postnatal pain from birth-related trauma, whether it be from vaginal delivery or caesarean section, may be another, less-discussed factor affecting breastfeeding outcomes. The objective of this study is to investigate how the actual experiences of birth and breastfeeding differed from the mother's pre-birth intentions, and the impact that any birth-related pain had on their breastfeeding experiences.

Methods

Study design

Data was collected over a one-month period through use of an online survey of UK-based women, all of whom had given birth to their youngest child within the last 24 months, initiated breastfeeding, and had completed their breastfeeding journey (n=1 000). The survey questions, survey structure, and subsequent data analysis and interpretation were derived and performed by the authors. The online survey was hosted by a specialist research agency.

The project utilised quantitative, online market research methodologies to ensure that a large enough representative sample could be obtained. Respondents were obtained from a specialist UK, young family panel via their standard processes, which includes adherence to Market Research Society guidelines and GDPR standards. The providers panel is made up of predominantly offline recruited pregnant women and mothers in the UK, who have all given specific consent to join the panel and receive survey invites. Standard demographics were obtained from respondents such as number of children, age, socio-economic group and geographical location, and tested to ensure that the sample was representative of the UK population (within the group that consists of women with young children). Of the respondents, 1 000 (87% of those polled) said that they had breastfed their youngest child at any time and had recently completed breastfeeding. It was critical to ensure that the population comprised only of those who said that they had completed breastfeeding, to ensure that the analysis was being conducted across the entire breastfeeding journey.

The survey itself was in two parts: the first survey examined plans and intentions around breastfeeding and birth, and what influenced these plans; the second survey was completed a few days later and explored actual experiences around breastfeeding and birth, any pain that was experienced post-birth and the impact this had, if any, on breastfeeding. All 1 000 participants completed both parts of the study and were included in the analysis.

Results

Breastfeeding intention and influencing factors

Of the 1 000 mothers that completed the study, 60% of them were first-time mothers. Out of the 1 000 mothers surveyed, 89% reported that they had a pre-birth intention to breastfeed their infant in some way, with 66% of them intending to exclusively breastfeed. Of those intending to breastfeed in some way, breastfeeding for six months or longer was the most common goal (Table 1).

| Q: thinking about your last pregnancy and planning for your child. What was your intention with respect to breastfeeding your child? Base: total sample (n=1 000) | |

|---|---|

| I wanted to exclusively breastfeed (breastfeeding or expressing only) | 66% |

| I wanted to mainly breastfeed (breastfeeding or expressing only) but use some formula | 20% |

| I wanted to mainly use formula but breastfeed (breastfeeding or expressing only) a bit of the time | 3% |

| I didn't want to breastfeed at all | 1% |

| I didn't really have a plan of any kind about breastfeeding | 10% |

| Q: what was your intention with how long you planned to breastfeed for? Base: wanted to breastfeed in some way (n=893) | |

| At least 3 months | 9% |

| At least 6 months | 34% |

| At least 9 months | 6% |

| At least 12 months | 23% |

| I didn't really have a firm plan on how long I wanted to breastfeed for | 25% |

| Other (please specify) | 3% |

| Q: when you were planning things before the birth of your baby, which of the following would you say that you knew or learnt? Base: total sample (n=1 000)* | |

| I didn't know any of the above at that time | 1% |

| Guidelines say that mums should continue to breastfeed in some way for up to 2 years | 21% |

| Guidelines say that mums should exclusively breastfeed for at least 6 months | 54% |

| Breastfeeding has health benefits for mum | 74% |

| Ensuring baby gets colostrum during the initial few days is beneficial | 81% |

| Breastfeeding has health benefits for baby | 85% |

| Breastfeeding from birth is best for baby | 86% |

Respondents were asked what influenced their breastfeeding plan. Key influencing factors included the benefits for the infant (known by >80% of respondents), health benefits for the mother (known by 74% of respondents) and the guidelines around breastfeeding for six months (known by 54% of respondents) (Table 1).

Actual experiences of breastfeeding

Despite 89% of mothers intending to breastfeed, only 45% were still breastfeeding by six months. This figure dropped to less than 25% at 12 months (Figure 1). Of those surveyed, 27% considered themselves to have exclusively breastfed, with the majority of mothers (58%) using formula at some point alongside breastmilk (Table 2).

| Q: which of the following statements best apply to breastfeeding the baby? Base: total sample (n=1 000) | |

|---|---|

| I exclusively pumped breastmilk (I didn't use any formula) all the way until I stopped breastfeeding | 2% |

| From the start I mainly used formula but occasionally breastfed or pumped | 6% |

| From the start I mainly used formula but occasionally breastfed or pumped | 10% |

| I used combination feeding (breastfeeding/expressed breastmilk feeding and formula) from the start | 21% |

| I exclusively breastfed (I didn't use any formula) all the way until I stopped breastfeeding | 27% |

| I started exclusively breastfeeding or pumping my breastmilk (didn't use any formula) but changed to combination feeding (breastfeeding/expressed breastmilk feeding and formula) later | 31% |

| Other | 5% |

| Q: were you able to totally follow your breastfeeding plan once your baby was delivered? Base: total sample (n=1 000) | |

| Yes | 50% |

| No | 50% |

| Q: what changed? Base: couldn't follow their plan (n=497)* | |

| I used less formula milk than I originally intended to | 0% |

| I breastfed for longer than I originally planned | 4% |

| I didn't/couldn't breastfeed at all | 13% |

| I used more formula milk than originally intended, later on once breastfeeding was established | 15% |

| I used more formula milk than originally intended, in the early days | 25% |

| I did breastfeed but not for as long as I originally planned | 60% |

| Other | 12% |

| Q: why did your original plan change? Base: couldn't follow their plan (n=497)* | |

| I stopped breastfeeding once I started weaning my baby | 1% |

| Going back to work | 3% |

| Personal choice | 10% |

| I experienced pain during breastfeeding that made me stop | 18% |

| I had problems breastfeeding; not initially but after a while | 24% |

| My own health issues | 26% |

| My baby's health issues | 29% |

| My baby was too hungry | 30% |

| My baby wasn't satisfied | 32% |

| I had issues breastfeeding initially | 47% |

| Other | 8% |

Exactly 50% of mothers surveyed felt they were able to thoroughly follow their breastfeeding plan. For those that were unable to follow their plan, the biggest change was not breastfeeding for as long as planned (60%). Using more formula milk either in the early days (25%) or later in their breastfeeding journey (15%) also scored highly (Table 2). Predominantly, the reasons contributing to this change in plan centred around issues establishing breastfeeding, concerns about the baby getting enough milk, and health issues of both mother and baby (Table 2).

Birth experiences and interventions

When asked about their birth experience, only one third of mothers (33%) said their birth went well and to plan, while a further 29% said the birth went very well, but not to plan. A further 37% of respondents felt their birth was difficult. Women underwent a wide range of interventions during the birth, with 38% receiving sutures afterwards, and a total caesarean section rate of 30% (Figure 2).

Experiences of pain following childbirth

Of the 1 000 women surveyed, 71% experienced discomfort or pain while breastfeeding. Nipple soreness, nipple pain, and breast-related symptoms relating to engorgement were all commonly reported (Table 3). A total of 183 women (26% of those who stated they experienced pain while breastfeeding) said that the pain they experienced was related to the birth itself. C-section was the biggest reason for this pain, cited by over 50% of these respondents.

| Q: did you experience any physical issues (eg discomfort, pain) while breastfeeding at all? Base: total sample (n=1 000) | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 71% |

| No | 29% |

| Q: which of the following issues did you experience while breastfeeding your child? Base: had issues (n=707)* | |

| I had an inverted nipple | 7% |

| My breast was itchy | 14% |

| My nipple was itchy | 15% |

| I was in pain from other sources which affected breastfeeding (eg birth/sitting related, c-section) | 26% |

| My nipple was bleeding | 33% |

| My breast felt hard/tight | 44% |

| My breast was sore/tender/swollen | 45% |

| My nipple was cracked/blistered | 58% |

| My nipple was painful | 62% |

| My nipple was sore/tender | 82% |

| Other | 10% |

| Q: what was the cause of the pain you were in (that wasn't caused directly by breastfeeding itself)? Base: pain from other sources (n=183)* | |

| I'd rather not say | 0% |

| General birth-related discomfort | 7% |

| Episiotomy | 10% |

| Stitches | 14% |

| C-section | 53% |

| Other | 17% |

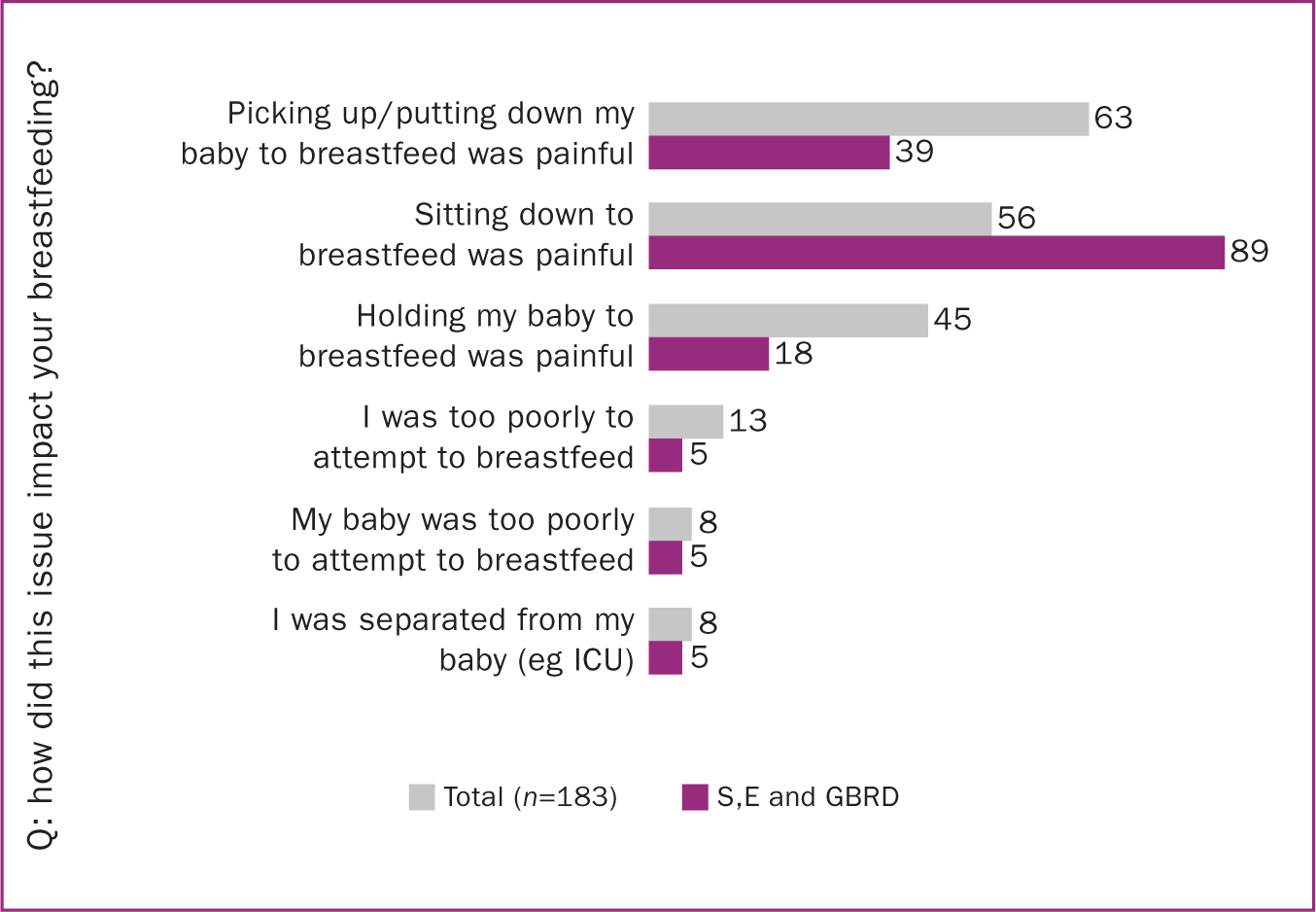

| Q: how did this issue impact your breastfeeding? Base: pain from other sources (n=183)* | |

| I couldn't attempt to breastfeed at all | 0% |

| I was separated from my baby (eg ICU) | 8% |

| My baby was too poorly to attempt to breastfeed | 8% |

| I was too poorly to attempt to breastfeed | 13% |

| Holding my baby to breastfeed was painful | 45% |

| Sitting down to breastfeed was painful | 56% |

| Picking up/putting down my baby to breastfeed was painful | 63% |

| Other | 4% |

| Q: what impact did this pain from this issue have on your breastfeeding? Base: pain from other sources (n=183)* | |

| I switched to pumping | 20% |

| I breastfed through the problem with no negative impact | 25% |

| I stopped breastfeeding completely | 26% |

| I had to breastfeed in an alternative position to be comfortable (eg lying down) | 33% |

| I breastfed less and introduced some formula feeds | 35% |

| I breastfed through the problem but it negatively impacted my mental health (eg I felt stressed, I dreaded each feed) | 40% |

| I needed assistance during breastfeeding (eg picking up/putting down my baby or getting into correct position) | 47% |

| Other | 0% |

| Q: overall, what impact did the pain from this issue have on your total length of time breastfeeding? Base: pain from other sources (n=183) | |

| I couldn't breastfeed at all | 0% |

| I stopped breastfeeding much earlier than I would have done without the issues | 47% |

| I stopped breastfeeding a little earlier than I would have done without the issues | 10% |

| No impact | 43% |

| I stopped breastfeeding a little later than I would have done without the issues | 0% |

| I stopped breastfeeding much later than I would have done without the issues | 0% |

Other causes included episiotomy, sutures and general birth-related discomfort (Table 3). These issues made breastfeeding difficult rather than preventing it, with mothers reporting that their pain made it difficult to pick up and put down their baby (63%), painful to hold their baby to breastfeed (45%) and difficult to sit comfortably when breastfeeding (56%). When the data was re-analysed to exclude women who had undergone a c-section, focusing only on those respondents who had sutures, episiotomy or general birth-related discomfort (S, E and GBRD), the percentage of respondents reporting that sitting down to breastfeed was painful increased to 89% (Figure 3). This equated to 16% of the total 1 000 women surveyed.

Impact of birth-related pain on breastfeeding and cessation of breastfeeding

When asked what the impact was of the birth-related pain they experienced (n=183), almost half of respondents (47%) reported that they needed assistance during breastfeeding, eg help picking up/putting down their infant. A further 38% had to breastfeed in an alternate position to be comfortable. A substantial number reported that the pain they were in contributed to them introducing more formula feeds (35%) or switching to expressing (20%). Only a quarter (25%) of respondents breastfed through the issue with no negative impact, compared to 40% who reported that they breastfed through the issue but that it negatively impacted their mental health. Of the surveyed mothers, the 26% who were experiencing pain from birth-related sources reported that it was a contributory factor in them stopping breastfeeding (Table 3).

Discussion

It is clear from this study that new mothers face a variety of challenges when establishing a sustainable breastfeeding relationship with their infant, even if they enter motherhood with a determination to breastfeed. The UK Infant Feeding Survey (UK IFS) reported an initiation rate of 81% with a breastfeeding prevalence of 69% at one week, 55% at six weeks and 34% at six months (IFF Research, 2013). The data presented here replicates this trend, with a high breastfeeding initiation rate, followed by a sharp reduction in breastfeeding prevalence in the weeks and months following birth.

However, interestingly, a higher percentage of respondents in this study reported they were still breastfeeding in some way at each timepoint compared to the UK IFS. This may reflect a genuine shift in breastfeeding success in the several years since the UK IFS, however it has previously been suggested that the UK IFS report underestimated breastfeeding rates (Quigley and Carson, 2016). Of the mothers surveyed, 60% were first-time mothers; it should be noted that while the experiences of first-time mothers often differ to those of mothers who have given birth previously, in this instance, differences between the two groups were not significant, allowing the data set to be analysed as a whole.

It is of note that combination feeding predominated, with most respondents using formula at some point alongside breastmilk. When discussing breastfeeding rates, the focus is often placed on exclusive breastfeeding, in line with the WHO's (2019) recommendation. However, the data presented here suggests that failure to fully consider those who combination feed may exclude the largest population of breastfeeding mothers, in the UK at least. Interestingly, a larger percentage of respondents felt they used more formula than planned in the early days than later, once breastfeeding was established. This may reflect an opportunity for increased education and support for mothers who have introduced formula ‘top-ups’ and supplementation in the initial days and weeks, to aid them in resuming exclusive breastfeeding, by supporting them to recognise their infant cues, and when there is a true need for supplementation. Early formula supplementation has been associated with triple the risk of breastfeeding cessation by day 60, and is significantly dose dependent, with increased numbers of formula feeds contributing to an earlier abandonment of breastfeeding (Walker, 2015). This suggests that provision of support and guidance to minimise the amount of supplementation used initially, and to reduce formula use once maternal pain subsides, may have a positive impact on duration of breastfeeding overall.

Exactly half of the mothers surveyed faced challenges while breastfeeding which made them change their plan. The most cited reason for the change of plan was ‘issues breastfeeding initially’, a broad term which likely covers a range of common issues well-characterised in published literature (Odom et al, 2013; Feenstra et al, 2018). These issues overlap with another common reason for changing plans: pain during breastfeeding which affected over 70% of the 1 000 women surveyed here.

Concerns that their infant was still hungry or unsatisfied scored second highest in the survey, consistent with previously published data identifying perceived insufficient milk supply as a commonly cited reason for early cessation of breastfeeding (Binns and Scott, 2002; Ahluwalia et al, 2005; Gatti, 2008). While the highest drop off from breastfeeding for this reason is during the first 1–4 weeks after initiation, it also continues to be the most common problem cited for several months (Binns and Scott, 2002; Ahluwalia et al, 2005; Gatti, 2008). This is despite true milk undersupply being unusual; one study investigating perceived milk insufficiency monitored actual milk production and reported that some women who had proven adequate supply at six weeks postpartum still reported that they felt their supply was insufficient (Hill and Aldag, 2007), while a second study to determine the relationship between perceived insufficient milk supply and actual insufficient milk production found no significant relationship between the two (Galipeau et al, 2017).

Over a quarter of respondents (26%) who couldn't follow their breastfeeding plan cited that their own health issues contributed to this change, with the same percentage reporting that pain relating to the birth impacted their ability to breastfeed (for context, nearly two thirds of this group reported nipple pain as an issue). Many of the interventions that women experience during birth, such as c-section, episiotomy and sutures, are associated with pain and a period of incapacitation and recovery, above and beyond the normal and expected discomfort of an uncomplicated birth (Borders, 2006; Declercq et al, 2008). Holding their infant to breastfeed, picking up their infant, and sitting comfortably to breastfeed were all painful for many respondents.

In addition to the obvious effect on the mother's wellbeing, this inability to find a comfortable, pain-free breastfeeding position may also exacerbate other issues through a negative impact on the infant's positioning, latch and duration of breastfeeding events. Poor latching is associated with pain when breastfeeding, and correct positioning and latch are essential for increasing milk supply and intake (do Espírito Santo et al, 2007; Brown and Jordan, 2014). Disturbed infant feeding behaviour may also negatively impact milk production (Brown and Jordan, 2014).

The impact of the mother's physical health on breastfeeding outcome was noted by Rajan (1994) who conducted a questionnaire-based study of mothers six weeks post-delivery. Women who reported they felt ‘well’ or ‘very well’ were almost twice as likely to be exclusively breastfeeding than those who felt ‘not very well’ or ‘not at all well’ (Rajan, 1994). Further analysis of the data found that problems caused by sutures, urinary frequency and the aftermath of a c-section were all significantly associated with the ability to breastfeed successfully (Rajan, 1994). We report here that a quarter of mothers who communicated birth-related pain which affected breastfeeding said it was a contributary factor in stopping breastfeeding; this was around 5% of the total women surveyed. It was more common that the pain and discomfort relating to birth made breastfeeding difficult as opposed to preventing it completely.

While it may not have prevented breastfeeding, it is important to note that of the 183 mothers with birth-related pain, 40% reported that although they continued to breastfeed, it negatively impacted their mental health. For comparison, only 25% stated that they continued to breastfeed with no negative impact. Pain after childbirth has been associated with an increased risk of postpartum depression (Gutke et al, 2007; Eisenach et al, 2008). Additionally, studies have reported a relationship between breastfeeding difficulties and maternal mental health issues (Brown et al, 2015; Chaput et al, 2016). These issues are likely intrinsically interlinked, meaning that any positive impact on maternal mental health through breastfeeding support can be further improved by concurrently supporting the new mother with any specific challenges or pain she is suffering relating to the birth itself.

This study provides a snapshot of the kind of challenges mothers felt had impacted their breastfeeding outcomes. When interpreting the findings, the retrospective nature of the study design should be considered; as the data collected was based on self-report and retrospective recall, it is possible that the mothers misreported their experiences —a consideration for any retrospective survey-based study. It should be noted that mothers of more than one child were not asked whether they breastfed their earlier children, while this is known to have an influence on breastfeeding experience, the omission of this question is not considered to impact the conclusions presented here. The substantial sample size of this study makes it a valuable data point in understanding the impact of post-birth pain in breastfeeding mothers; a more expansive, prospective study is being planned to validate and build on these initial findings.

Interestingly, upon review of similar published research in this area, it appears that the design of many of the surveys/questionnaires may have failed to specifically record data relating to birth-related pain. As an example, the extremely comprehensive survey-based study by Odom and colleagues (2013) of 1 177 mothers did not appear to have a response option to allow capture of maternal post-birth pain as a contributory factor in breastfeeding cessation. In survey-based studies, where the respondent may be limited by the response options provided, the failure to include specific post-birth pain options may contribute to a general underestimation of the problem.

When considering the challenges that a new mother experiences in establishing and maintaining breastfeeding, it is essential to consider everything the mother is going through, and the cumulative pain and discomfort she is experiencing from all sources. While physical issues directly relating to breastfeeding and the nipple itself are by far the most common, the impact of pain following the birth should not be underestimated as a contributory pressure on the mother's wellbeing, mental health and breastfeeding choices. The view of pregnancy and birth as ‘normal’ processes may mean the expected discomforts and possibilities of pain following labour and delivery are not adequately acknowledged or expected (Stainton et al, 1999).

For a new mother, juggling the emotional, hormonal and physical changes post-birth, the exhaustion of caring for a new infant and the discomfort and pain that is often associated with the establishment of breastfeeding, it is perhaps unsurprising that post-birth pain and discomfort may be the ‘straw that breaks the camel's back’; contributing to a shift away from the pre-birth breastfeeding plan. Further research should be considered to increase understanding of the causes, and impact, of postnatal pain in breastfeeding women, with careful consideration given to study design to ensure that all contributing factors are captured. This is particularly important for studies which utilise survey-based tools for data collection. It is possible that increased acknowledgment and support for mothers in the management of birth-related pain and discomfort in the early postpartum period may have a positive impact on mothers achieving their breastfeeding plan.