In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is when an egg is fertilised by sperm outside the human body, usually in a culture dish (Franklin, 1997). This technique was developed by Sir Robert Geoffrey Edwards, a physiologist, and Dr Patrick Christopher Steptoe, an obstetrician and gynaecologist in the 1970s, as a means to treat female infertility (Mulkay, 1997). The first baby born as a result of IVF, Louise Brown, was delivered via a caesarean section in July 1978 at Oldham Hospital in Greater Manchester (Brown, 2018). Louise celebrated her 40th birthday in 2018, and has two sons conceived without the use of any assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs). In 2018, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology ([ESHRE], 2018) reported that a global total of more than eight million babies had been born from IVF since the technology was first pioneered.

The development of IVF technology has also enabled several other applications which extend beyond treating female infertility (Sarojini and Marwah, 2015). Such applications include circumventing male infertility, facilitating people undergoing various medical treatments, such as chemotherapy, to preserve their gametes, and women to extend their fertility through egg freezing (Edwards et al, 1999; Crawshaw et al, 2009; Inhorn, 2015; van de Wiel 2015; Baldwin 2019). Additionally, other applications based on IVF have empowered people who may not have otherwise considered bearing a genetically related child to have more reproductive choices. Such people include those with a genetic condition and/or same-sex couples. These choices include preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), ie testing an embryo for the disease its parents' are affected by before the embryo is transferred into a uterus in the hope of establishing a pregnancy, using donated gametes, and surrogacy (Kaur and Border, 2020). There is potential for ARTs to expand to include editing embryos to prevent genetic disease. The development of ARTs has thus led to a rise in non-traditional pregnancies (NTPs) (Thompson, 2007).

Non-traditional pregnancies

NTPs are those which thwart conventional pregnancies, ie pregnancies which would otherwise be contingent on sexual reproduction and natural biology. NTPs include those involving geriatric mothers, people with genetic conditions, surrogate mothers and same-sex couples (Thompson, 2007). Geriatric mothers are women who have their first pregnancy aged 35 years or older (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists [RCOG], 2011). Geriatric mothers result from women being able to bypass age-related infertility through IVF (RCOG, 2011), and women purposefully planning to circumvent age-related fertility by freezing their eggs (Baldwin, 2019). While late motherhood may be welcomed and celebrated by many women, it can generate high-risk pregnancies. This is because older women are at higher risk of many medical complications. Examples of such complications include gestational hypertension, prolonged labour, stillbirth and postpartum haemorrhaging (RCOG, 2011).

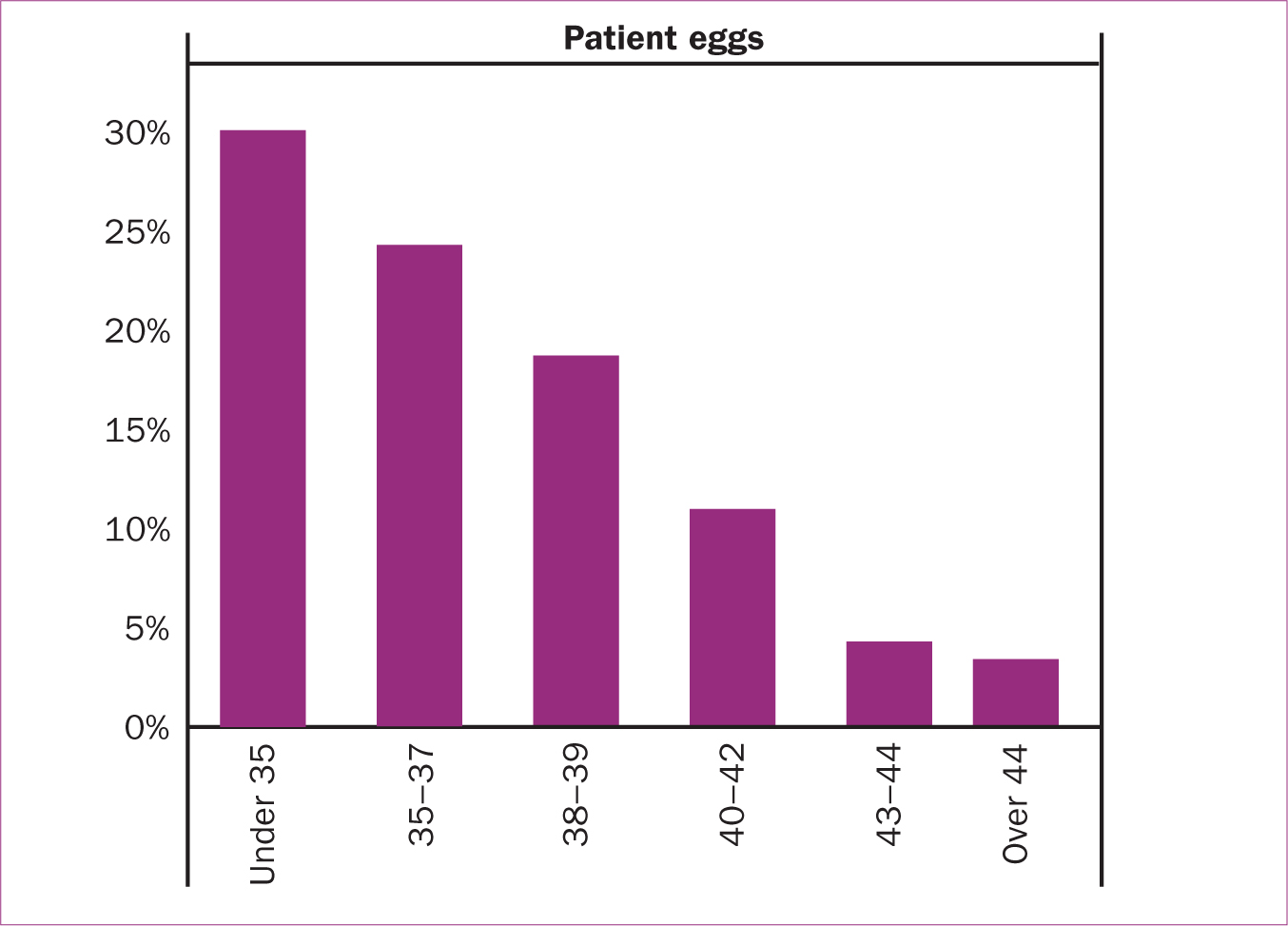

Women with underlying health conditions, including health conditions which can result from having a genetic condition, are also often considered to be high-risk (Franklin and Roberts, 2006). However, women with high-risk factors will all still require a level of routine midwifery care (Narayan and Morton, 2015). Women aware of their high-risk status may require additional emotional support to alleviate their anxieties, especially if their pregnancy has been achieved following the use of ARTs (Cooper and Glazer, 1999; Stevenson and Hershberger, 2016). This is because IVF has a very modest average success rate of one in four, and this rate steeply declines as maternal age advances; this is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Success rate of IVF in relation to maternal age

Figure 1. Success rate of IVF in relation to maternal age

The physical, emotional and financial expense of IVF can therefore make any resulting pregnancy from it even more valuable to the parents, who may have invested all they have in their desire for a child (Kaur, 2020). Additionally, a review of articles on high-risk pregnancies found that women experiencing such pregnancies had worse emotional status than women with low-risk pregnancies (Rodrigues et al, 2016). Such emotional states include heightened anxiety and higher levels of stress, which may have pronounced implications antenatally, and greater intensities of depression postnatally.

For other people, ARTs may enable them to hope for at least partially, genetically related child if they cannot gestate a pregnancy themselves. This is true for same-sex couples, particularly gay men, and people with other biological/health limitations which could make them dependent on gamete donation and/or surrogacy to achieve their reproductive goals (Mamo, 2007; Smietana et al, 2018). This could mean that antenatal and postnatal care may involve greater levels of consideration than would be typically extended. This is because in addition to the surrogate, the intended parents may wish to be part of their surrogate's care (MacCallum et al, 2003; Horsey, 2010).

Furthermore, postnatally, the surrogate mother and the baby are likely to be separated, at least upon discharge from delivery settings. This would mean that community care for the mother and baby could be required at two different sites (Jadva et al, 2003; Horsey, 2010). Ensuring that both parties are well may require more/different support than would traditionally be tendered. The ongoing expansion of ARTs is therefore clearly likely to impact midwifery practices to some extent, and so, midwives should engage in discussions on how to support woman and their families who have invested in the use of ARTs to achieve their pregnancies and (hopefully) their resulting child(ren).

Methodologies

The expansion of ARTs to include a developing technology which could be used to edit human embryos before they are transferred into a uterus, was explored using a three-phase research design. All three phases of the research were designed in adherence to the British Sociological Association's ([BSA], 2017) guidelines on conducting ethical research; they also received ethical approval from the University of Cambridge's Department of Sociology's Ethics Committee. The three phases of research were conducted between March 2018 and October 2019.

The first phase of the research consisted of a mixed-methods online survey of 521 citizens of the UK, aged 16–82 years, 52% of whom self-identified as female and 48% as male, on ‘Understandings of genetic editing and its potential uses with human reproduction’. Table 1 and Table 2 support this claim.

Table 1. Respondents' age

| Age ranges | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

| 16−19 | 48 | 9.2 | 9.2 | |

| 20−24 | 85 | 16.3 | 25.5 | |

| 25−29 | 78 | 15.0 | 40.5 | |

| 30−39 | 118 | 22.6 | 63.1 | |

| 40−49 | 91 | 17.5 | 80.6 | |

| 50−59 | 68 | 13.1 | 93.7 | |

| 60+ | 33 | 6.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 521 | 100.0 | ||

Table 2. Respondents' gender

| What gender are you? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

| Female | 271 | 52.0 | 52.0 | |

| Male | 250 | 48.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 521 | 100.0 | ||

The sample size was based on achieving a confidence level of 95% with a 4%–5% margin of error. This meant that 95% of the approximated total population that could have responded to the survey were likely to have responded in the same way as actual respondents. The approximated population was 48 043 809; this was derived from 2011 census data in the UK. The sample was nationally representative of the age ((in combination with factors of reproduction) and sex of citizens in the UK based on 2011 census data from the UK. Additionally, within in the sample, 36.7% of respondents self-identified as being religious (see Table 3)-the six main religions were represented within this percentage. The six main religions are considered to be Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism and Sikhism (Garner, 2004). Finally, 29.2% self-identified as being affected by a genetic condition (see Table 4).

Table 3. Respondents' religiosity

| Are you religious? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

| Yes | 191 | 36.7 | 36.7 | |

| No | 330 | 63.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 521 | 100.0 | ||

Table 4. Affected by genetic conditions

| Have you ever been affected by a genetic condition? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

| Yes | 152 | 29.2 | 29.2 | |

| No | 369 | 70.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 521 | 100.0 | ||

The survey was distributed via social media and email to ensure that people of all ages, from the six main world religions, and/or affected by genetic conditions were represented within the sample. This method of distribution was also considered to be the most feasible and effective way to reach the UK's wider public, ie its citizens, in an eco-friendly and timely manner.

The survey had four sections; the first section was on knowledge and understanding of genome editing, the second was on hypothetical practical applications relating to factors of disease, the third was on regulation and ethics, and the final section captured demographic information. Data from the survey was imported to SPSS to be cleaned and thematically analysed. SPSS is a software largely used to analyse quantitative and statistical data (IBM, 2020). Cleaning, in this context, refers to ensuring that all the data is formatted correctly; this can include modifying data so that it is formatted correctly (Schmidt, 1997; Wright, 2005). For example, changing ‘f’, ‘woman’ and ‘girl’ to ‘female’ and copying and pasting answers to replace ‘see previous answer’ or ‘same as before’ where appropriate.

The qualitative answers to the survey were also imported to NVivo for coding and thematic analysis. NVivo is software used to find common themes, reasons and/or meanings in qualitative data (QSR International, 2019). Coding is an process in which data is categorised to facilitate analysis (Gibbs, 2007). Findings from the survey were then used to inform the subsequent phases of research. The second phase of research consisted of semi-structured interviews with experts and professionals who could speak to the landscape of ARTs in the UK, specifically in relation to genome editing technology which could be used to edit human embryos; this possibility is referred to as human germline genome editing (hGGE).

The experts and professionals included scientists, UK government officials, and staff from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA); they were selected based on the relevance of their respective expertise. The third phase of the research comprised of structured interviews with 21 people who are affected by genetic conditions. Data from all the interviews were transcribed and also imported to NVivo for thematic analysis. Participants in the third phase were assigned pseudonyms during transcription.

The data from all three phases of the research were triangulated to produce the findings shared in this article. The research findings should be of interest to midwives because the implications of them could impact midwifery practices; thinking about these impacts and how midwives may respond to them and/or incorporate them into midwifery practices may therefore prove to be useful for continuing professional development.

Research findings and discussion

Triangulated findings from the primary research suggest that hGGE could be added to ARTs in the foreseeable future as a means to enable people with genetic conditions to prevent their child(ren) inheriting their condition. This finding is based on only 4.8% (25/521) of respondents to the survey being directly opposed to hGGE being legalised in the UK as a reproductive choice; 66.22%–86.56% (345–451/521) of respondents feeling that hGGE should be allowed as various factors of disease were explored; the technology being able to adopt frameworks used for existing ARTs for sound regulation (according to experts interviewed in the second phase of research), and people with genetic conditions being supportive of enabling the technology for such purposes. The following qualitative answers from participants in the third phase of research support the latter finding:

Virginia: [hGGE] should be legalised. The key reason why I hold that opinion is because I am disabled myself, I have a genetic condition, and personally I would not want to have a child or bring another person into this world with the same genetic condition as myself. I think life with this disability is a struggle in this ableist world. Frankly, I would not choose to have this condition if I had the option, therefore I would not choose it for someone else either.

(Female, 21, has muscular dystrophy)

George: I actually look into genome editing quite a lot because I have Charcot Marie Tooth disease, which is a genetic condition. And I feel that if it'd been possible for me to be, like fixed early on, I feel that that's almost like a necessity, like it needs to be done.

(Male, 34, has Charcot Marie tooth disease)

The potential addition of hGGE to ARTs would be of significance to midwives because it could result in higher levels of people with serious genetic conditions gestating a pregnancy. Such people are likely to be considered high-risk, and/or to require greater levels of support than people without such genetic conditions (Yali and Lobel, 1999). As mentioned above, even high-risk pregnancies still require a level of midwifery care (Narayan and Morton, 2015). This is important to note, because to date, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) has been relatively unsuccessful for the minority which do try to utilise the technology, with only 38% of established pregnancies resulting in a live birth (HFEA, 2018). This means that most midwives would have been unlikely to care for a woman who has used such ARTs but this could change if hGGE were to be introduced to ARTs, whether in the UK or abroad (Horsey, 2010; Lovell-Badge, 2019). Additionally, obstetricians may not have supported people with various medical complications through pregnancy, birth and puerperium.

The concept of individuals/couples travelling abroad to access ARTs is not a new phenomenon, and if hGGE were to become available outside the UK, presuming that traveling abroad to access hGGE is reasonable (Inhorn, 2015; Kaur, 2020). Of the respondents to the survey, 65.64% (342/521) felt that citizens of the UK should be allowed to travel abroad to access hGGE; this percentage increased if the underlying reason for accessing the technology abroad were to be for the prevention of disease. Transnational care has implications for midwifery practices, insofar as, the use of ARTs in the UK is highly regulated by the HFEA under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (HFE) Act 1990, as amended in 2008. The same cannot be said for other countries (Jackson, 2001). As such, if women were to seek ARTs abroad, the care they receive, and/or any malpractice may not be documented and/or accessible to healthcare practitioners in the UK (Bell et al, 2015; Rosemann et al, 2019; Kaur, 2020). This could impact the holistic care that midwives are expected to provide for women and their (growing) families, even those with NTPs (Berg, 2005; Sittner et al, 2005).

Additionally, if/when hGGE is introduced to ARTs as a reproductive choice for the prevention of disease, this could increase the amount of live births from people who are affected by genetic conditions (Lovell-Badge, 2019). Depending on how the parents' genetic condition affects them, they may need extra support in caring for their child; such situations may therefore require referral to specialists midwives and/or other support (Yali and Lobel, 1999; Ogbuehi and Powell, 2015). In this vein, universities, trusts and the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) may benefit from considering whether having specialist midwives or all midwives, trained in the range of ARTs and their relation to midwifery practices would be a pragmatic approach to contemplating a rise in NTPs and their outcomes; this could be done by developing e-learning modules for registered midwives and adding such content to student midwives' syllabi. This may become increasingly important to consider as ARTs are increasingly used for purposes that extend beyond infertility-such as those shared in the background section.

Furthermore, while PGT and hGGE are both based on preventing a child from being born with the genetic condition which affects its parents, this is the only condition that should be prevented (Ormond et al, 2017; Lovell-Badge, 2019). This means that the resulting child still holds risks for having any other disease, including the nine diseases routinely screened for via the blood spot test (NHS, 2017). Midwives should be prepared to explain/reiterate this to parents who may use such ARTs to conceive their child(ren), particularly if more people choose to use them. Another prospect of hGGE is that any person born following the use of the technology, at least initially, may require additional tests and ongoing health reviews to ensure that no adverse side-effects have been encountered (Thompson, 2019).

The extent to which midwives will be/are willing to be involved in such surveillance is a matter worth ruminating before decisions are made. Although ARTs are primarily concerned with conception, the impacts the use of ARTs have evidently interplay with midwifery practices. Keeping abreast of advances to ARTs, potential ARTs, and their applications should therefore be of interest to midwives. This is because decisions regarding the births and monitoring of children born from various ARTs may have direct implications for maternity documentation and care. Midwives could therefore benefit from collectively voicing their options on such matters, particularly on how they could affect midwifery practices and the care midwives are able/should be able to provide for women. This may become increasingly important as such technologies continue to advance and potentially new forms of NTPs are encountered.

While researching the potential applications of hGGE, other possible applications of ARTs were brought to attention. One such application is uterine (womb) transplants and the possibility that transwomen and transmen may try to establish a pregnancy using a combination of ARTs (Alghrani, 2016). This possibility, like hGGE, is also foreseeable (Jones et al, 2019). These potential applications are envisaged due to continuing social and scientific advances (Doudna, 2020; Kaur and Border, 2020), and are likely to continue to develop. How midwives will/could respond to these within clinical settings, is a topic which could benefit from further discussion and/or research. Such NTPs are likely to challenge routine clinical observations, could potentially raise issues in maternity related documentation (Horsey, 2010; Sarojini and Marwah, 2015), and will have repercussions antenatally and postnatally.

Conclusion

The expansion of ARTs and their various implications are likely to increasingly impact midwifery care. This argument is based on existing ARTs, such as egg freezing and surrogacy, and potential ARTs, such as hGGE, conceivably leading to a rise in NTPs which may require greater and/or alternate levels of care. Potential NTPs include higher numbers of geriatric mothers, high-risk women, surrogate mothers and trans-mothers (Sittner et al, 2005; Horsey, 2010; van de Wiel, 2015; Alghrani, 2016; Baldwin, 2019). All these NTPs could be exacerbated by the introduction of hGGE to ARTs due to the reproductive choices the technology could enable. To this end, this article concludes that because advances in and applications of ARTs are likely to generate an ongoing rise of NTPs, midwives could benefit from contemplating this prospect within their continuing professional development and prepare for this foreseeable eventuality.

Key Points

- Since the introduction of in vitro fertilisation in the late 1970s, it has been used to enable a number of other applications which have led to an increase in non-traditional pregnancies

- Current applications of IVF technologies beyond infertility include egg freezing, egg donation, preimplantation genetic testing and surrogacy

- Non-traditional pregnancies include those involving geriatric mothers, people with genetic conditions, surrogate mothers and same-sex couples

- Non-traditional pregnancies are more likely to require greater variations of typical midwifery care and/or antenatal and postnatal support

CPD reflective questions

- How does the mode/means of conception affect the provision of midwifery care?

- Will the expansion of assisted reproductive technologies require additional documentation?

- What implications do surrogate pregnancies pose on antenatal and postnatal midwifery care?

- What support is available for parents with genetic conditions?

- Are all non-traditional pregnancies high-risk pregnancies?